Author of Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, Tim Lawrence shares the parties that have inspired him the most, from Hot Wednesdays at the Hacienda, to Feel Real at The Gardening Club, Body & Soul in New York and beyond.

If anyone knows how to party, it's author and promoter Tim Lawrence. The British born party boy, turned academic, has not only hosted parties with the late DJ legend David Mancuso but also written three books on the dance floor experience; Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music, looking into disco, decadence and beyond; Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, and Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor; a detailed history of 80s NY, and how the dance floor not only brought different worlds together but laid the foundations for Hip Hop, House and Techno. Featuring interviews with over one hundred DJs, party hosts, producers, musicians, artists, performance artists, dancers and more - including Keith Haring, Jean Michel Basquiat and Fab 5 Freddy - it's a must read for anyone with a passion for understanding how music subcultures are directly shaped by social and political events of the time.

Fast forward to the here and now, and Tim works at the University of East London, where he teaches music and is the Professor of Cultural Studies. He is also the co-founder of Lucky Cloud Sound System, who have been hosting legendary Loft-style parties in London since 2003; some of the best of which saw night turn into day at Shoreditch's notorious now sadly defunct Light Bar. We caught up with Tim, on the re-release of Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, to find out the parties that have inspired him the most… From Hot Wednesdays at the Hacienda, to Feel Real at The Gardening Club, Body & Soul in New York and beyond, these are the clubs that changed his life...

Hot, Wednesdays at the Hacienda, Manchester, summer of 1988

"One summer, while studying Politics and Modern History at Manchester University, I stayed in the city to work at a camp for kids. Some non-uni friends had heard that the Haçienda was supposed to be good on Wednesdays so we went to take a look. That night I heard house music on a sound system for the first time and was immediately captivated. It must have taken me all of ten seconds to get from the entrance to the nearest podium and hurl myself into the tribal dance. I later learned that we had walked into Hot, one of the formative nights of the Summer of Love."

The Gardening Club London

Feel Real at the Gardening Club, London, c. 1992

"This was the first place where I felt as though I'd found a party home. A collective of four DJs led by the Rhythm Doctor, Feel Real held down Friday nights in this intimate basement spot in Covent Garden. It was the first time I was exposed consistently to New York house and I soon started to give the Rhythm Doctor a lump of money to buy me whatever he was buying, i.e. I was hooked. When "Little" Louie Vega showed up to play a guest spot I more or less decided I was going to move to NYC."

Rhythm Doctor and Little Louie Vega, The Gardening Club

Sound Factory Bar, NYC, 1994

"I moved to NYC in the autumn of 1994 to study on the doctoral programme at Columbia University (I'd grown a little weary of my day job) and dance to Louie Vega's selections at the Sound Factory Bar every Wednesday night. At the time every Louie mix was essential and the SFB was the place where he played them first. It was my first experience of the multicultural NYC dance floor. The live shows were also something else—India, Barbara Tucker, Tito Puente… I felt like I was at the epicentre of the dance music universe."

Body & Soul, NYC, 1996

"I'd heard Joe Claussell play in Dance Tracks, where I bought records every Friday night, and I'd danced to François Kevorkian's selections in the basement of the Sound Factory Bar, where he supported Louie Vega and mainly stuck to disco classics. But something took over when Joe and François teamed up with Danny Krivit to launch Body & Soul in Club Vinyl. It was fun to see three DJs share the decks and each introduced their own flavour to create what seemed like the perfect blend. The dancing was intense!"

The NYC Loft, 1997

"I interviewed David Mancuso for the first time in the spring of 1997 and soon after went to my first Loft party. Initially I didn't know what to make of the experience. The party took place in a private apartment, the sound system sounded positively quiet and at the peak of the party there might have been six people in the room. But there was something compelling about the open atmosphere, the clarity of the sound, the range of the music and the absence of DJ trickery, and by the time Mancuso held his 28th anniversary party the following February the floor was ready to explode with community happiness."

David Mancuso

The Loft, London, 2003

"As Love Saves the Day was going through production, David Mancuso approached me and Colleen "Cosmo" Murphy to propose that we start to host Loft-style parties in London. Joined by Jeremy Gilbert, we held our first party at the Light in Shoreditch in June 2003. David stayed in London for five days to shape the party in the image of the NYC Loft, from checking the size of balloons to visiting sound system companies to working out where to position the equipment to thinking through the lighting. Attended by friends and friends of friends, the party was one of the most joyous I've attended. Thanks to the foundations laid by David over a period of years the parties are still running today."

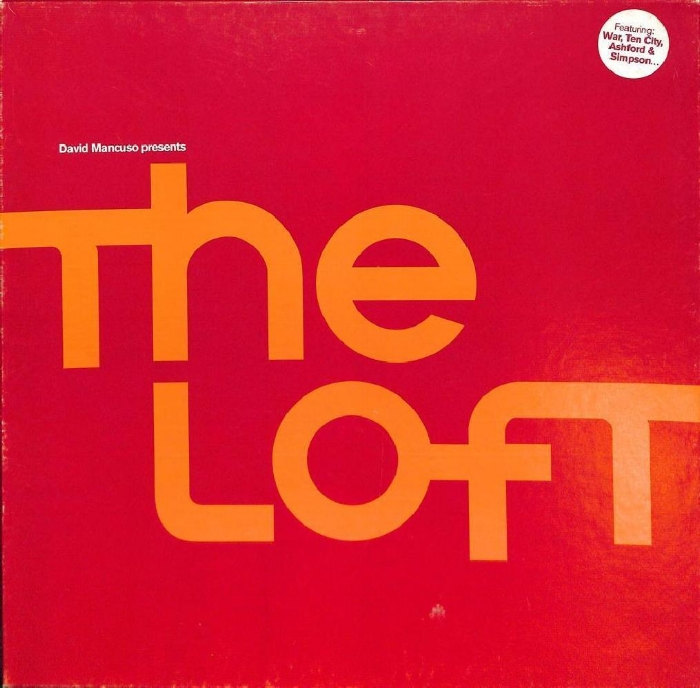

David Mancuso presents The Loft, 1999

The NYC Loft, 2016

"I travelled to New York in October 2016 to launch a new book, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-83, and timed the trip to coincide with a Loft party. David was kind enough to offer for the book to be sold at the party but didn't attend, having pulled back from attending his own party incrementally, in part because, radically anti-ego in outlook, he wanted to get to a situation where the parties would run successfully without him. The community vibe, beautiful sound and shimmering atmosphere of the October party confirmed that his dream had been realised. He passed away a month later."

This article was originally published on i-D, you can access it here (pdf).