House music is disco's revenge. So said Frankie Knuckles, reflecting on the charged history of the genre, which emerged in hometown Chicago in the middle of the 1980s. In this case home, to quote Gil Scott-Heron, is where the hatred is, or was. The disco sucks movement had its spiritual and organisational headquarters in the city, and the organisation's campaign reached its vitriolic climax when the celebrity rock DJ Steve Dahl detonated fifty thousand disco records during the halfway break of a baseball doubleheader. Metaphorical retribution arrived, according to the Knuckles, when dance artists, revisiting the disfigured disco of Dahl's melted vinyl, melded it into house. Revenge indeed.

House music's birth, however, has been largely mystified by this Darwinian story of destruction, survival and evolution. The genre might have received its abbreviated name from the Warehouse, where Knuckles, proud and defiant, continued to spin dance grooves in the aftermath of Dahl's headline-grabbing histrionics. But the sound of house emerged from an acute and unexpected angle that was in many respects cut off from the past. And while Knuckles played a heroic role in keeping disco alive in a city where so many chanted for its death, the acclaimed "Godfather of House" was a secondary figure when it came to pushing the mid-eighties incarnation of the genre.

An alternative genealogy of house might propose the following. That the key musical reference point for house wasn't disco, but a range of off-the-wall sounds that spanned late sixties rock and early eighties new wave. That the genre's key venue was not the celebrated Warehouse or the magisterial Power Plant (where black gay men were dominant), but the ramshackle Music Box (where the crowd was black and straight-leaning-towards-pansexual). And that its most influential spinner was not the ambassadorial Knuckles, but the deviant Ron Hardy ¾ a towering figure who, extraordinarily, was never interviewed before his untimely passing in 1992.

The heavyweight presence of New York has made it difficult to establish this alternative history. Drenched in disco, the city was initially suspicious of house, with Larry Levan, one of its most progressive DJs, notoriously slow to pick up on the genre. When Manhattan's spinners finally caught on, they tended to favour disco-flavoured cuts such as JM Silk's "Music Is the Key" over the obtuse, alien sounds of records such as "Acid Tracks". Experienced through New York's eardrum, Chicago house sounded like an offshoot of New York disco. This was, and remains, disconcerting for many Chicagoans.

The strange life cycle of Chicago house in the UK only added to obfuscation of house music's original trajectory. The disco-derived "Love Can't Turn Around" went Top Ten before house had had a chance to create a buzz amongst dance aficionados. Then, following the successful release of Virgin's debut techno compilation, Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit, Chicago house was cast (yet again) as the intimate and conservative cousin of disco—a music that, in contrast to techno's heroic and radical engagement with the future, was determined to look (or listen) backwards.

UK acid house culture, which referenced Phuture's sublimely freakish "Acid Tracks", soon came to signify a broader dance movement that was awash with bright yellow smiley faces, stylistically challenged baggy t-shirts, interminable debates about the meaning of "acid" that rarely referenced the music, and a new mythology that situated the culture's roots as much in the sunny holiday resort of Ibiza as the windswept post-industrial landscape of Chicago.

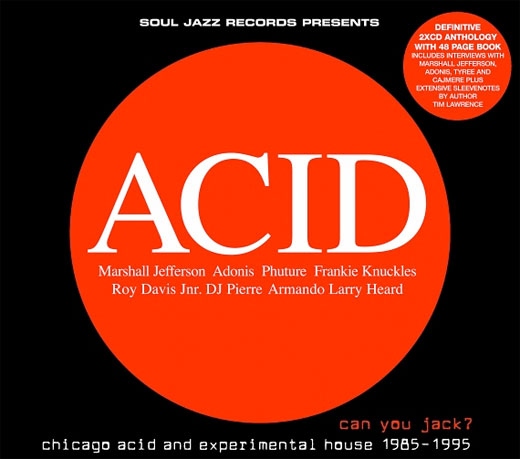

House wasn't born this way. Not in Chicago, at least. And this album—which focuses on experimental house records, many of them rarities, many of them released between 1985 and 1988—opens up an opportunity to retell the story of Chicago house that gives belated emphasis to the music's progressive roots.

* * * * *

Chicago boasts a long history of radical, roots-oriented music making. The city played a central role in the evolution of the blues from the 1920s to 1940s, when it channelled the raw guitar work of the Mississippi Delta into the circuitry of electronic instrumentation, and in the late 1940s and 1950s it became a key centre for R&B, turning out artists such as Curtis Mayfield, Major Lance, the Dells, Gene Chandler, Dee Clark and the Chi-lites. "By the late 1960s," writes Robert Pruter in his book Chicago Soul, "the predominant recording activities in the city were in the soul field."

Ironically, Chicago produced no DJs, remixers or clubs of national significance during the 1970s. Its most famous spinner, Frankie Knuckles, hailed from New York and travelled west only when his career (established at the Continental Baths) lost its early momentum (after the bathhouse closed, Knuckles found himself spinning at the less-than-hip Stargate Ballroom). Meanwhile disco commentators never considered the Warehouse, which became virtually synonymous with Knuckles, to be anything more than a regional footnote, at least in its 1977-79 incarnation. Of course these commentators penned their copy in New York, but if they had travelled to Chicago they would have surely described the Warehouse as variation of party spaces such as the Loft, the Gallery and, most spectacularly, the Paradise Garage.

Knuckles and the Warehouse did play an emotional and sustaining role in the face of the disco sucks campaign, and the intense devotion felt by dancers and DJs for this music was illustrated when, some time around 1980/81, the staff at Importes [sic.] Etc, the main dance store in Chicago, introduced the label "house music" in order to channel the stream of requests they would receive from customers in search of Knuckles's non-commercial selections ¾ mainly disco, post-disco R&B and a healthy smattering of imports, many of them from Britain (new wave) and Italy (Italian disco). "House" was, quite simply, an abbreviation of "Warehouse" and it soon became part of the established scenester lexicon. But the Warehouse had no direct role in the house music that emerged as a distinctive musical genre from 1984 onwards.

Mid-eighties house music was rooted, instead, in the unnatural technological soil that was being cultivated by a new generation of researchers, engineers and musicians. The most influential figure in this movement, Robert Moog, launched the first commercial monophonic modular synthesizer in 1967. The following year Columbia Records commissioned a series of electronic and modern compositions that used the technology, including Walter (now Wendy) Carlos's acclaimed rendition of Bach, Switched on Bach. The Beatles used the Moog on their experimental White Album, which was released in 1968, and Giorgio Moroder employed the synthesizer as a font of gimmicky sounds on "Son of My Father" ¾ its first appearance in pop. After a few songs he gave up on the new technology. "The audience response wasn't really there," he says, "and I was always a commercial composer-producer."

Kraftwerk took synthesizer technology—which acquired a polyphonic capability with the commercial release of the Oberheim Four Voice in 1975—more seriously, deploying it as an avant-garde sound source on the cerebral Autobahn and Trans-Europe Express, and Moroder returned to the Moog soon after, this time in order to generate futuristic sounds for "I Feel Love", the final track on his journey-through-the-decades album with Donna Summer, which revolved around a hypnotic oscillating synth line. Although drum machines such as the Chamberlain Rhythmate, Wurlitzer's Sideman and Korg's Dunca Mata had started to appear on the market from the late 1940s onwards, their purpose was to generate dinky "samba" and "bossa" lines for amateur organ players, so Moroder ended up finding most of his percussion sounds from the Moog. "We managed to create a snare and a hi-hat but we couldn't find a punchy enough bass drum," he says. "Eventually we just did an overdub."

Roland launched its first preset drum machines—the TR-33, TR-55 and TR-77—in 1972. Six years later the company came out with the CR-78, which allowed music makers to programme their own patterns. Then, at the end of 1980, the Japanese manufacturer introduced the TR-808, its most "convincing" drum machine to date (even though the equipments sounds were all synthetic). Phil Collins was one of the first artists to deploy the TR-808 in the musical mainstream, although other musicians complained of its artificial sound. When the widely loathed Dutch outfit Starsound used a drum machine in order to join-the-dots on "Stars on 45", an abridged version of the Beatles greatest hits that was released in 1981, the technology seemed to be destined for permanent ridicule.

On the surface, the TR-808 appeared to be absurdly limited, capable as it was of producing just sixteen basic sounds (bass drum, snare drum, low tom, mid tom, hi tom, rim shot, handclap…). What's more, the sounds weren't particularly convincing. As music critic Kodwo Eshun notes, there were no drums in these drum machines, and their sounds (electronic pulses and signals) were utterly different from live drums. All of the sounds could be tweaked through rotary controls, however, and that was exactly what Afrika Bambaataa and Arthur Baker tried out during the recording of "Planet Rock"—which included TR-808-generated beats and the quivering orchestral keys of the Fairlight synthesiser—in 1982. The emergent genre of electro soon became synonymous with these aggressive beats. The TR-808 no longer seemed to be quite so feeble.

Drum machine technology took another leap forward when Roger Linn released the LM-1 around the same time that Roland came out with the TR-808. The LM-1 was entirely sample-based and was considered superior to the TR-808 for this reason. The drums on Prince's 1999 were almost entirely sourced from the LM-1, and other high-profile artists, including the Thompson Twins, Stevie Wonder, Gary Numan, Depeche Mode, the Human League, Jean-Michel Jarre and the Art of Noise, used the equipment. The five thousand dollar price tag, however, was prohibitively expensive for most musicians.

Roland released the hybrid TR-909, which used both analogue and sampled sounds, in 1983 (the samples comprised of recordings of "real" drums stored digitally). Only ten thousand machines were manufactured before the company discontinued the model and replaced it with the TR-707, which, like the Linn, drew on an archive of exclusively digital samples. More or less simultaneously, Yamaha launched the DX7, the first entirely digital synthesizer. Artists approved of the sparklingly, life-like sounds of the DX7 so much that the market for firsthand analogue synthesizers (including the original Roland machines) virtually evaporated overnight.

Chicago music makers didn't hang around for the market to collapse. A number of DJs rotated "Mix Your Own Stars"—the B-side of "Stars on 45"—to mix between records; Kenny Jason was reputedly the first Chicago spinner to use a "live" drum machine in his DJ sets; and Jesse Saunders, who was putting on parties for high school kids at the Playground, wired up a TR-808 to his turntables during the summer of 1983. These and parallel practices were interesting but far from extraordinary. "The sound of the drum machine wasn't that different," says Saunders. "Kraftwerk had been using electronic drum pedals. It was already in use."

Jesse Saunders and Jamie Principle laid down the first Chicago house tracks. Principle, an ardent fan of English new wave bands and a disciple of Prince, recorded the dark, stripped down, haunting and distinctly European "Your Love, which started to get reel-to-reel play in late 1983. Soon after Saunders, who soon linked up with Vince Lawrence, the son of a small-time Chicago record label boss, put together "On and On", a copy of a bootleg remix by Mach that included snippets from "Space Invaders", "Funkytown" and "Bad Girls". "On and On" was pressed up first—at the beginning of 1984.

Principle and Saunders were equally influential. Principle inspired his peers because "Your Love" teased open the awesome possibilities of a new musical sound that combined the faux futurism of British new wave with a mesmerising dance groove. Saunders, for his part, created a different kind of wonder. Few, if any, thought that "On and "On" was any good, but almost everyone saw Saunders sell thousands of copies and achieve an remarkable local fame. Saunders got the money, the girls and the cars, all from punching a few keys on a drum machine. "We didn't think we could touch Jamie, but Jesse's bullshit sold, and we could visualize doing better than that," says post office worker Marshall Jefferson, who was keeping half an eye on the unfolding scene. "Jesse was responsible for the house music boom. Without Jesse Saunders, the non-musician would not be making music."

* * * * *

There is almost no point in attempting to impose a calm, coherent chronology on the house music scene of mid-eighties Chicago, which gathered steady momentum during 1984 before the floodgates opened in 1985. The naivety and desperation of many of the record makers combined with the off-the-hoof machinations of the local label entrepreneurs created a recipe for vinyl chaos. What's more, there was no established practice, ethical or otherwise, for music makers and publishers to fall back on in order to reference the dos and don'ts of the music business.

To complicate matters further, the Chicago house music economy was only partially organised around the traditional process of pressing up vinyl. Whereas labels were dominant in the New York food chain, they were all but absent in Chicago, which meant that the grey economy of tapes took on a heightened role. It was quite normal for a producer to lay down a track, distribute it on tape and see it pressed up on vinyl several months later. What happened in between was anyone's guess.

Records that were pressed up independently took on a heightened scatological existence, especially if they proved to be popular. The more established labels, which might have rejected the track first time around, would suddenly scurry to put it out. Contracts, usually extremely flimsy affairs, were often an afterthought. And so a virtually unmappable exchange of tapes and acetates began to emerge in the second half of 1984 and accelerated during 1985. There was little order, but a great deal of excitement.

Into this cauldron of activity, two broad categories of house music emerged: house that, referencing the past, continued to live in the present, and house that, articulating an experimental present, reached for a tangible future. The first type of house, drawing on disco as its supreme inspiration, sought to rejuvenate seventies dance within the framework of eighties technology. The second type of house, which is rarely distinguished from disco-driven house in historical accounts, had no direct connection to its seventies predecessor. House was bipolar ¾ and at least fifty percent avant-gardist—right from the start. It is the radical half of house that is the concern of this album.

Naturally, New York discophiles heard more than a faint echo of their favourite genre in the new house sound of Chicago. "When house first came out, it sounded a lot like disco, but really raw and stripped down," says Danny Krivit, a resident DJ at Downunder and Laces Roller Rink at the time. "'Love Is the Message' was a blueprint for house music and MFSB, with Earl Young on drums, were also the band behind a lot of the things that Frankie would play. He played these records on a good sound system and he used the three-way crossover to create a stripped down effect. He basically made old disco sound like house." Impressionable young kids, who lacked the musical skills of their disco forebears, listened and learnt. "The people who were going to listen to him used their new drum machines and synthesizers to emulate what they would hear in the club. Most of them were DJs, not musicians, and they just improvised."

Billboard columnist Brian Chin was initially cautious in his response to house, which he perceived to be essentially derivative. "Chicago house started out as a subset from Philadelphia," he says. "'Music Is the Key' was a rip-off of 'Music Is the Answer' by Colonel Abrams. Chip E 'Like This' was [ESG's] 'Moody' sideways. 'Jack Your Body' was [First Choice's] 'Let No Man Put Asunder'. Larry Heard 'Mystery of Love' was more original—it wasn't recognizably after any particular record ¾ but house was generally a hard-driving variant of disco." ("Like This" by Two of a Kind, which foregrounds its indebtedness to the mutant disco of ESG, can be added to the list. The record appears on this album.)

Looming over mid-eighties Chicago, disco was an impossible act to follow for the city's producers and artists, who didn't even bother to dream about pulling together the multi-tiered musical ensembles and studio time that was run-of-the-mill standard for so many disco productions. It wasn't just a matter of finances, or lack thereof. It was also about technical training. What would these young Chicago producers have done with all of these musicians and studio time? The answer is: nothing.

"The reason that house was stripped down was no one could afford to deal with live bands, plus a lot of people who made that shit weren't theoretically trained," says Lil' Louis, a rising DJ name who was spinning at the Hotel Continental. "You could hear that in the records. They were almost a dissident version of what real music should be." But one thing was clear. Disco was dope, and a subtle (or not-so-subtle) reference to a favourite song was the easiest way they could pay their respects ¾ and snatch what was required.

Yet while some Chicago's house producers gazed longingly in the direction of disco central (New York) and its key satellite states (Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Miami), others gazed into space, searching for new co-ordinates, hoping to break with the past and gamble with the future. Marshall Jefferson and Larry Heard led the way in trying to sound as strange, even as unmusical, as possible, and while they drew on the same technological pool as the discophile set they also deployed the equipment in such a different way that some would allege they misused it. This kind of house music wasn't something that gradually evolved out of the template established by Hurley and co. It was there from the start.

Jefferson, a rock freak who actively disliked disco, paid a visit to an equipment store in the summer of 1984 and started to lay down a slew of hard-edged, non-referential recordings. Virgo's "Go Wild Rhythm Tracks" (featured on this album) was put together with the less than helpful assistance of Vince Lawrence (whose 1986 track "Dum Dum" also appears on this album) and the seminal "I've Lost Control" (another inclusion) featured the deranged vocals of Sleezy [sic.] D as well as the demented gurgling of the 303. Neither of these recordings contained a self-conscious reference to disco, and the sound of the seventies was equally absent from the slew of recordings that Jefferson put together between 1984 and 1985.

Larry Heard, meanwhile, had grown bored playing drums in a local band and, at the end of 1984, purchased a Roland Juno 6 synthesizer and a TR-707. Heard went home and produced three tracks in one day: "Washing Machine" (angular, otherworldly, trance-inducing), "Can You Feel It" (technical, melancholic, low key) and "Mystery of Love" (lush, warm, gently percussive). In 1985 Heard teamed up with vocalist Robert Owens to re-record "Mystery of Love", and the duo went on to record "A Path", "You're Mine", "It's Over" and, with Harri Dennis, "Donnie". "Beyond the Clouds"—featured on this album—was laid down after Heard added a Roland Jupiter 6 keyboard to his home studio in late 1985. "I was intrigued by synthesizers," he says. "I wasn't a writer. I wasn't a composer. I was just trying to do something creative. I knew I could play the keyboard in a traditional way, but I didn't want to do that."

These recordings were still indebted to seventies dance music. It is hard to imagine, for example, "I've Lost Control" or "Beyond the Clouds" happening (or at least finding a consumer market) without disco's emphasis on polyrhythm, the extended break and the rhythm section, plus the introduction of chant-like clipped vocals that drew on whittled down, floor-friendly themes. The journey from "work that body" to "jack your body" was a reasonably short one. Yet there was also an intentional break with the lush sophistication that came to define a good deal of disco in the second half of the 1970s, and the decisiveness of this rupture has yet to receive proper recognition.

House's forward-looking producers—Jefferson and Heard, with Adonis, Chip E and others—were stepping into a long-established practice of western avant-garde music making that received its most forceful expression when the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo published The Art of Noises on 11 March 1913. Russolo's manifesto called for the creation of a new form of music that would be built around machine-like noise rather than the entrenched instrumentation of the symphony orchestra. "We cannot much longer restrain our desire to create finally a new musical reality," wrote Russolo. "Let us break out!" Dance music acquired a futuristic edge with Kraftwerk and Giorgio Moroder, and the baton was subsequently picked up, according to many, by the street freaks of electro and the bedroom boffins of techno, with house producers playing only a supporting role of catch-up. If that.

"House music to me is nothing more than an extension of disco," says Juan Atkins, the senior representative of the "Belville three", the founding fathers of Detroit techno, who hailed from suburban Belville (Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson completed the troika). "Chicago came out with its own version of techno a couple of years down the road with Larry Heard and Marshall Jefferson, but they didn't call it techno because we already had the term, so they called it acid house." Atkins adds: "It was a little take-off. I think there was somebody there trying to emulate a Detroit record… It seems like an awful coincidence that our records were selling so well in Chicago and all of a sudden acid house came on the scene."

The best known of these records ¾ and the one that Atkins refers to ¾ is "No UFOs", Model 500's debut release on Metroplex, which came out in the spring of 1985. The record, produced by Atkins, entered the Billboard charts in August 1985, having weaved its way into Chicago a little earlier thanks to May, who was travelling Chicago regularly to visit his parents. In contrast to Atkins's earlier electro releases, which were recorded with the group Cybotron and were similarly saturated with ideas of the alien other, "No UFOs" used a four-four bass drum, and this, according to the Detroit producer, was the reason why the record landed so successfully in Chicago.

Yet while "No UFOs" was played on radio in Chicago—Atkins credits Farley "Jackmaster" Funk of the Hot Mix Five as being the first radio jock to rotate the track—it is less than clear if it was rotated in the clubs that counted. Chicagoans insist that it wasn't, and that Detroit techno only established a foothold in the city with the release of May's "Strings of Life" and "Nude Photo". But even if Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy did play the Model 500 debut, the daring originality of Jefferson and Heard's earliest productions is beyond dispute, and these were laid down before "No UFOs" made the westbound journey to Chicago. Chicago, in other words, didn't follow Detroit into the future. The Windy City was running a dead heat with the Motor City and it might have even been ahead, at least when it came to four-on-the-floor.

Techno aside (and it really was aside in Chicago during 1985 and 1986), differences between the two principal strains of Chicago house shouldn't be allowed to obscure their similarities. Whatever the relationship to the past and the future, house producers were part of a pioneering posse of alternative musicians whose principle activity was to piece together rather than play music. That was because the rapid spread of drum machines, synthesisers and sequencers (sampling had yet to take hold in house) changed the nature of musicianship, seemingly for good. While it was still entirely viable to learn to play a traditional instrument in real-time before attempting to record music, that kind of skill was no longer fundamental to the recording process.

Jesse Saunders might have regarded himself as a conventionally skilled musician, but most Chicago producers were more interested in finding than playing. Jacques Attali commented in Noise, published in 1977, that the musician was becoming a spectator of the music created by his computer." The French philosopher and music theorist added: "One produces what technology makes possible, instead of creating the technology for what one wishes to produce." Following this dictum, house music was (in the words of Simon Reynolds, writing for Melody Maker in February 1988) "assembled, not born". The distinction between music technology and music creation was becoming harder to define. And the difference between Chicago house and New York disco was become easier to hear.

* * * * *

Following the runaway local success of "On and On", Larry Sherman, the owner of the only pressing plant in Chicago, decided to set up his own house music label, which he dubbed Precision Records. Then, at the beginning of 1985, Sherman set up a label with Jesse Saunders, the most prolific (if not most creative) figure in the new genre. Vince Lawrence came up with a name for the label ("Tracks") and Sherman, a notoriously bad speller, the legendary lettering ("Trax"). "Wanna Dance?" by Le' Noiz, a pseudonym for Saunders, was the first release.

Sherman and Saunders were less gung ho when it came to releasing other people's music. They rejected Marshall Jefferson's "Go Wild", which the producer brought to them soon after the label was formed. (Jefferson responded by setting up his own label in order to release the record.) They also turned down Chip E's "Jack Trax" EP, which arrived on their doorstep in the spring. (Chip E formed his own label and paid Sherman to press up a single acetate of the recording.) Then, towards the end of the year, they passed on Jefferson's Virgo EP, which featured two tracks by Adonis, including a remake of "I've Lost Control", titled "No Way Back". (Jefferson put the record out himself, and when Sherman heard how "No Way Back" was going down he released it on Trax.)

By the end of 1985, Chicago's record label scene had divided itself into two: established independents and fly-by-night vehicles for producers who were being cut out. Trax was almost old school, having been in operation for almost an entire year, and DJ International, which was opened around the middle of 1985 by local record pool boss Rocky Jones, with Steve "Silk" Hurley in initial tandem, was also becoming a major player. Trax and DJ International soon developed an intense rivalry that was based less on their differences than their similarities: both Jones and Sherman ran "streetwise" operations in which artists, seduced by up-front cash sweeteners, rarely made as much money as they were due.

Artists who couldn't get released on Trax or DJ International often set up their own labels, flagging the move towards a highly flexible, deregulated and transient market in music recording along the way. Jefferson's Other Side was one, Heard's Alleviate was another. Their labels might have looked like they were the musical equivalent of vanity publishing, but whereas most self-published books don't sell, these records sold in their thousands. The problem was simple. There weren't enough labels around, and the ones that were up and running were still getting to know the market.

To all intents and purposes, Sherman controlled the blood flow. All records travelled through his pressing plant and numerous eyewitnesses testify to his willingness to siphon off the most profitable material pretty well as he pleased. If a reject record turned out to be a local hit, who could stop Sherman from pressing up copies behind the artist's back? The Wild West (or, alternatively, neo-liberal) business model was carried over into the mogul's use of raw materials, which were often more cooked than raw. In order to maximise profits, Sherman regularly resorted to using recycled rather than virgin vinyl and the result, which apparently didn't cause the plant owner too many sleepless nights, was a spew of a poor-quality pressings. "Importes Etc. had a lot of complaints from customers," says Charles Williams, who worked in the store. "But in the end they had no choice because these were the only versions."

The real powerbrokers in the Chicago house scene, however, weren't the labels but the Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hard, the two most influential spinners in the city. And even though Knuckles is commonly called the "Godfather of house", Hardy was the more influential DJ between 1985-88 period ¾ the period that marked the rise of house, and which is the focus of this album.

Both Hardy and Knuckles were operating in new conditions. During the 1970s there was little, if any, direct contact between musicians and producers on the one hand and DJs on the other. Record companies were the effective gatekeepers of the dance music economy, opening or barring the way to club play. Musicians and producers rarely went to the clubs where their music was being played, and key remixers such as Tom Moulton (who didn't like clubs) and Walter Gibbons (who was too busy DJing) weren't around to do the legwork. So it was left to the promotional reps of the record companies to hand deliver the latest sounds to the DJs, or drop off boxes of records at the local record pool.

This system began to break down in the late 1970s. Having entered the dance market at an ungracefully late moment, record companies pulled back with even less poise when the western-wide recession decimated music sales. By the early eighties, the gulf between the companies and the producers/artists had widened thanks to the wave of new, comparatively cheap technologies, which encouraged music makers to piece together rudimentary bedroom studios and press up records ¾ well away from the companies. By the time Chicago's fledgling house producers started to make records, it was easier to take a tape to Ron Hardy or Frankie Knuckles ¾ either in person or via a friend ¾ than it was to get a record released by one of the city's companies. And the contrasting personalities of the two DJs, combined with distinctive identities of their crowds, resulted in the emergence of distinctive dance worlds.

Having split with Robert Williams when the Warehouse closed in June 1983, Knuckles opened his own venue, the Power Plant, in November 1983. He was widely considered to be the more progressive and skilled DJ throughout 1984, and his crowd, which was largely composed of knowing and mature ex-Warehouse dancers, as well as some younger, more obviously streetwise elements, bolstered his reputation. "The Plant was located at 1015 North Halsted Avenue, in the 'back yard' of one of Chicago's most notorious public housing projects, Cabrini Green," says Alan King, a Warehouse and then Power Plant devotee. "Due to its proximity to Cabrini Green, the Plant drew a very interesting mix of people ¾ the more eccentric, often gay, former Warehouse crowd, as well as a more 'thuggish', generally straight element from Cabrini. It was very interesting to watch the communal power that Frankie and the music he played had on folks from very different walks of life. While some referred to house music as 'fag music', the hardest, straightest folks from Cabrini also became captivated regulars at the Plant."

The erudition of the Power Plant dancers also meant they had "high standards" and this, combined with Knuckles's penchant for expertly produced sounds and the inaccessible architecture of his towering booth, meant that the venue was comparatively closed to the rudimentary home-made tapes of Chicago's first wave of house producers. The devotion to disco—including the dark disco of groups such as the Skatt Bros.—was accentuated by the memory of Steve Dahl. Having been told that their beloved music sucked, dancers at the Warehouse, and then the Power Plant, were doubly determined to guard its survival. The crowd, in other words, could be just as picky as their spinner when it came to new music.

Hardy, for his part, was considered to be relatively conservative when he was recruited by Williams to play at the new Warehouse, which was situated in the old home of the Schwinn Bicycle company, located at 1632 South Avenue. Born into a jazz family, Hardy had played at a string of Chicago clubs ¾ including Den One and Carol’s Speakeasy—before travelling to California in the late seventies. He returned to the Windy City in the early eighties and led a life of relative obscurity, but Williams "thought he was pretty good" and "had the potential to develop himself into a better DJ" if he was given his own space.

The new Warehouse opened for business around the same time as Knuckles triumphantly launched the Power Plant and was forced to shut down soon after. Williams's new club, it seemed had little going for it. Hardy was playing a less interesting selection of records than Knuckles, and the new Warehouse was much less impressive in terms of all-round finish than the Power Plant. So, acknowledging that he wasn't going to win back his core black gay crowd anytime soon, Williams reopened his venue as the Music Box and started to try and draw in an alternative clientele. "The Music Box became more heterosexual than homosexual," says Williams. "A lot of gay people came along, but it wasn't as gay as the Warehouse. It introduced another group of people into the scene."

The new crowd didn't burst onto the scene out of nowhere. Some had danced at the original Warehouse, but most got their first taste in variety of less celebrated spaces. One of the most significant was known as the Loft, which was an entirely separate entity from David Mancuso's New York party, despite the shared name (the organisers, like almost everyone else, hadn't heard of Mancuso's subterranean space when they opened in 1980). Running in parallel, Saunders put on huge high school parties at the Playground, where he played a mix of disco, R&B, new wave and electro that was similar to sets of Kenny Carpenter and John "Jellybean" Benitez, both of whom were attracting similarly young straight black, Latino/a and Puerto Rican crowds at the reincarnated Studio 54 and the Funhouse. Having been excluded during the 1970s, straight "kids of colour" were finding their way into clubs en masse for the first time.

It was at the Playground that Keith Farley (who became Farley Keith Williams, then Farley Keith, then Farley "Funkin'" Keith and finally Farley "Jackmaster" Funk) got his first DJing gig and then shot to local fame when he joined the Hot Mix Five, which was formed in 1981 and also included Kenny "Jammin'" Jason, Mickey "Mixin'" Oliver, Ralphie "Rockin'" Rosario and Scott "Smokin'" Silz. "It was called Saturday Night Live, Ain't No Jive, Chicago Dance Party," says Silz. "We started off playing R&B dance music and we gradually became more progressive. In 1982 and 1983 we started playing a lot of imports from Italy and Canada, and then we got into house music. We played records from Jesse Saunders and Wayne Williams." Listening figures shot through the roof. "The show was number one. We had a thirty share of the Arbitron rating in the Chicago market, which was just incredible."

The Hot Mix Five soon became synonymous with WBMX—the mixers played on Friday nights as well as a daily Hot Lunch Mix and Traffic Jam session—and they also put on parties for local high school youths. "We took dance music from a very lean time period to the height of house music," adds Silz. "It used to be every kid wanted a baseball glove and a bat. It became every kid wanted two turntables and a mixer. All of a sudden everybody wanted to be a DJ. We were the force in bringing it to the masses."

While these events never came close to generating the same kind of underground cachet as the Warehouse, they nevertheless introduced dance music to thousands of youngsters and established an embryonic network that would go on to form an important part of the largely black straight crowd that gravitated to the Music Box. When some of these kids ¾ and their friends—started to record dance music, it was only natural that they would take the tapes to their local DJs. Hardy received the lion's share.

That was because Knuckles was relatively inaccessible, not just physically, in terms of the foreboding design of his new booth, but also psychologically, with regard his intimidating superstar (superstar in the relatively small world of Chicago Clubland, that is) status. Knuckles could be approached, and producers were certainly keen to give him their records, but he nurtured a reputation for accepting only high quality productions and a not entirely appetising rumour had it that the DJ cut up tapes he didn't like. The hurdles were formidable and the success stories fairly infrequent

Hardy, in contrast, was less of a star and had less of a reputation to protect. The less exalted base from which he had to operate suited the spinner, who stayed closer to the floor, and the people who headed in his direction were precisely the straight black youths and friends of straight black youths who were developing the nascent sounds of house. Tapes and acetates started to trickle in Hardy's direction during his stint at South Indiana Avenue, and when the Music Box relocated to the R2 Underground at 326 North Lower Wacker Drive the trickle turned into a flood.

"Ron Hardy got adventurous when he went to the Underground Music Box," says Marshall Jefferson. "He started taking tapes from everybody. I gave him fifteen tapes through Sleezy D and he played all of them. Frankie wouldn't take tapes. He tried to keep a level of quality and I don't think he really understood what was going on. 'I've Lost Control' was the biggest thing in the Music Box. I don't think Frankie played it." Chip E, who sold records to Hardy at Importes Etc., also found it physically easier to get tapes to the Music Box spinner. "Ronnie and Frankie were at different levels," he says. "With Frankie you almost had to have an invitation to the booth ¾ it had to be something that was planned before. But when I went to the Music Box Ronnie would put it on whatever I gave him, almost without listening." If Chip E couldn't get into the Music Box booth, he would just stretch out an arm and hand his latest tape to Hardy. "Ronnie was always more accessible."

The minimal-to-the-point-of-cheapskate design of the new Music Box complemented the shifting selections of the venue's DJ. The room, long and narrow, was painted black. Stacks of speakers lay at one end of the room and the DJ booth was positioned at the other, as if someone had set up a makeshift club in a dark and gloomy hallway. The sound system was loud but poorly defined, with the tweeters and midrange on the verge of permanent disintegration. The only source of light emanated from a couple of strobes, which flashed out visual warnings of sonic disorientation. It was as if the club physically embodied the dark, stark tapes that were being thrust in Hardy's direction.

Hardy developed a stylistic signature that matched the edginess of his selections at North Lower Wacker Drive. He started to play records fast (plus-eight fast). He violated established DJing etiquette and began to rotate his favourite tracks several times in succession. And, flying in the face of musical convention, he started to play tracks backwards via his reel-to-reel. "Ronnie took a real liking to 'It's House'," says Chip E. "He put it on reel-to-reel and started playing it backwards. Everyone loved it. People were coming into the store asking for the backwards version."

A hardening heroin addiction propelled the DJ's shift to an uncompromising style. "Ron had personal family problems that caused him to start doing the wrong kind of drug," says Robert Williams. "I'm not saying that Frankie didn't do anything, but he didn't do the wrong one—the one that was addictive. Ron started on heroin." Williams participated in the ritual but managed to survive its potentially pernicious effect. "I knew I could dibble and dabble, but I was very cautious and very mindful of what would happen if I got carried away. I used it as a recreational drug on occasions and didn't take it seriously. But Ron's brother had OD-ed and there were other family tragedies." Heroin made the music seem slower to Hardy, who responded by pushing up the speed controls. "That was why everyone thought Ron played with more energy than Frankie."

The predominantly young straight black crowd at the Music Box lapped up the madness. "It was full of urban guys from the west side and south side of Chicago," says Byron Stingily, who was introduced to the scene by Vince Lawrence, an old college friend. "Guys would dance with their arms locked around each other and jump around." Hardy's followers also jacked, which involved them thrusting their whole bodies forwards and backwards spasmodically, as if possessed by a demonic rhythm, and in so doing they inspired dance-driven cuts such as Chip E's "Time to Jack" as well as Hurley's "Jack Your Body". "The entire lyric for 'Time to Jack' was 'Time to jack, jack your body,' because that was all that was important," says Chip E. "People didn't need to hear a story. 'Time to jack, jack your body' — that was the story right there."

Power Plant dancers also jacked, yet they remained convinced of their own superiority. "The Power Plant had more disco sophisticates than the Music Box," says Andre Hatchett, a Warehouse regular who followed Knuckles to his new venue. "We were more knowing. We were the crowd. They were just our seconds, our hand-me-downs!" There can be little doubt, however, that Hardy's dancers had more energy than their Power Plant counterparts and, having received less education in the nuances of quality music, they were also happy to be taken on an extremely rough ride. "I went to the Music Box," adds Hatchett. "I didn't like it because I was a Frankie fan. Frankie kept a certain tempo and there was more of a groove. Ron Hardy had a more frantic tempo. Playing the reel-to-reel backwards started with Ron Hardy."

Contrary to popular folklore that has conferred the status of "Godfather of House" upon Knuckles, it was Hardy who lay at the fulcrum of house music's earliest, wobbliest, most experimental and most exhilarating incarnation—and it was Hardy who broke most of the records featured on this album. Knuckles kept dance music alive in the post-disco sucks era, inspired the term "house" via his selections at the Warehouse and went on to play a selection of house records that passed his scrupulous standards. But it was Hardy who was hungry for the new sounds of house, who accepted tapes over his booth, who played them with barely a listen, who encouraged novice producers to keep on producing and who established a consumer base for these fresh sounds. "I give Ron Hardy and his crowd credit," says Hatchett. "They invented house."

* * * * *

The brainchild of Earl "Spanky" Smith, "Acid Tracks" (included on this album) was inspired by Ron Hardy. Having left Chicago for California in the summer of 1984, Spanky returned when his friend Herb Jackson told him about the new club. "Herb said I had to come back, just to go to the Music Box," says Spanky. "I haven't returned to California since." Around the beginning of 1985, Spanky persuaded his sixteen-year-old buddy DJ Pierre (who had been spinning records since the age of thirteen) to visit the venue. "It changed his life, too," adds Spanky.

Some time later, Spanky and Pierre visited another friend, Jasper, who owned a Roland TB-303. Spellbound by the equipment's seemingly magical ability to synchronise the bass and the drum pattern, Spanky decided he had to buy a Roland for himself. His initial search yielded no results: Roland had discontinued the model and the main equipment outlets had sold out. "Eventually I found one in a second hand store for two hundred dollars," he says. "I spent my last dime on it."

Following the long established and extremely serious tradition of experimental music making, Spanky took the TB-303 home and, along with Jackson, started to press buttons he didn't understand. "After a while this strange sound popped up," says Spanky. "It was programmed into the machine. I thought it was slamming. I could picture Ron Hardy play it in the Music Box." Spanky called DJ Pierre. "Spanky had a drum beat going and the 303 was making all these crazy sounds," says DJ Pierre. "I thought it sounded interesting. Then I started to twiddle some knobs and the sounds became even weirder."

Spanky and his gang had pressed a button that was supposed to sound like a live bass guitar, but the imitation was poor and when the friends started to mess about with the frequencies the result was positively strange. "We were already going to the Music Box and hearing weird shit," says DJ Pierre. "We were already attuned—Ron Hardy had trained our minds—so the bass didn't sound like noise. It sounded like something you could dance to."

Spanky and DJ Pierre took a tape of the record (provisionally dubbed "In Your Mind") to the Music Box and, standing outside the club in the bitter cold, waited for Hardy to arrive. When the spinner arrived he listened to their cassette and said it sounded OK, and later on that night he played the track. "The first time he played it the crowd didn't know how to react," says Spanky. "Then he played it a second time and the crowd started to dance. The third time he played it people started to scream. The fourth time he played it people were dancing on their hands. It took control over them. Ron Hardy said, 'That's a great track!'" DJ Pierre adds: "Frankie Knuckles wouldn't have played it."

Spanky and DJ Pierre went to the Music Box for the next fortnight and then took a three-week break. During that time a friend approached them and said that Hardy was spinning an amazing track, which the dance floor was referring to as "Ron Hardy's Acid Tracks". The friend played a tape of the record to Spanky and DJ Pierre. It was "In Your Mind". "There was a rumour that they put acid in the water at the Music Box," says DJ Pierre. "I don't know if it was true or not, but we now had a new name for our record."

Following a Music Box performance of "Move Your Body"—actually titled "The House Music Anthem" and released on Trax in the summer of 1986—Spanky, DJ Pierre and Jackson approached Marshall Jefferson to see if he would produce "Acid Tracks". Jefferson, who had already toyed with the 303 on "I've Lost Control", agreed. "I tweaked the 303 before I recorded the track, whereas they tweaked it during the recording," he says. "I liked theirs better than mine."

According to Jefferson, there wasn't a great deal for him to do. "I sat in the studio and watched them. Larry [Sherman] told me he didn't want to put the record out unless I produced it. Since I recommended the project, I wanted to make sure it got taken care of." Jefferson introduced one significant change, slowing the record down from 126 to 120 beats per minute. "Marshall told us, 'New York has got to get into it!'" says DJ Pierre.

"Acid Tracks" was released under the moniker Phuture, and the first song on the B-side, titled "Phuture Jacks" (also included on this album), recycled the name. "We were sitting in a restaurant and a friend of ours called Tyrone, who was nicknamed Yancy, came up with the name 'Future'," says Spanky. "We thought that somebody would have already used it so we decided to call ourselves 'Phuture'." Given that "Acid Tracks" sounded like it had crash-landed in Chicago from some dark-and-twisted dystopia, the name was fitting. "The future was part of our lives," adds Spanky. "We weren't copying a sound that was already out there. We were creating a sound that you would expect to hear in the future."

Order and tranquillity reigned for about half a second. Armando released "Land of Confusion", ostensibly the second (or third if Sleezy D is counted as the first) acid house track, which the Phuture team enjoyed (Armando's "Downfall" appears on this album). After that, mayhem ensued, with an estimated sixty to one million acid house tracks being released in the slipstream of "Acid Tracks". Jefferson ¾ and it's not entirely clear if he's being serious or not ¾ blames DJ Pierre, who apparently revealed the TB-3030 secret to the rest of the world, for the avalanche.

The subsequent outpouring of acid releases included a good number of make-some-quick-money imitations, but also gems such "This Is Acid" by Maurice featuring Hot Hands Hula (included on this album), the cunningly titled "Acid Track" by Adonis (whose "Do You Want to Percolate?" also makes an appearance), and "Acid Over" by Tyree (another inclusion). "The crucial element in acid is that the bass line really carries the song," Tyree told Simon Reynolds in an interview for Melody Maker in February 1988. "It's the modulation of the frequencies of the bass line that keeps the track moving, keeps it hot."

Ron Hardy broke these and scores of other acid house releases at COD's, the Music Box having shut down some time around the end of 1986/beginning of 1987. Robert Williams eventually joined Hardy at his new spot, but it never became known as the Music Box, and Hardy subsequently left COD's for the Power House, where Knuckles had held his final Chicago spot before leaving to play a residency at Delirium in London in September 1987. (Knuckles, who was unable to detect any temporary, let alone lasting, value in acid house, returned to Chicago in December and then left for New York in January 1988.)

Hardy played alongside Steve "Silk" Hurley at the Power House and in the spring of 1988 the venue was renamed the Music Box. "A lot of the hardcore people who really loved the [Music Box] Underground at 326 didn't like the Power House," says Jamie Watson, who started to go out in the summer of 1988. "The Power House was a huge space compared to 326 and it didn't have the same atmosphere. The next generation was beginning to come through and a lot of the people who did their thing at the Underground felt they were too old to be partying with teenyboppers."

For many, 1988 was the year the Chicago scene experienced an irreversible downtown. Local authorities reigned in the clubs and WBMX went off air, all of which prompted Mixmag, whose attention was shifting sharply in the direction of New York, to announce in its July issue that the Chicago club scene was "dead". But while New York and New Jersey were now challenging Chicago as key centres of house music production, artists based in the Windy City continued to turn out experimental music, even if the circumstances of their release were often murky.

Tyree's "Acid Crash"(included on this album) typified the bedlam. Originally released as "Video Crash" on Rockin House Records in 1988, the record was bootlegged in New York and re-released as "Acid Crash" on House Musik later on that same year. Tyree had no cause to get upset, having drawn heavily on "Video Clash", which was released on Dance Mania in 1988, in order to make the record in the first place. And Lil' Louis—according to many, Chicago's third most important DJ, even he is widely considered to have been a "long third" behind Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles—couldn't get too upset, either, because his own contribution to the recording was disputed.

Jefferson (surely the most influential Chicago producer of the mid-eighties) laid down the first version of "Video Clash" with Kym Mazelle around 1986. Jefferson says that Lil' Louis was over his house "every day" during this period, always on the hunt for new music, and when the DJ laid his hands on Jefferson's distorted, virtually insance "Video Clash" he cut out Mazelle's vocal and turned the stripped down tracks into his signature tune at the Future (the old Playground, which Lil' Louis took over in the mid-eighties) and the Bismarck (a hotel where he put on huge pizza parties for a young crowd).

"It was a crazy song," says Lil' Louis. "I used to play it at my parties and people would beg me for it." Jefferson was characteristically blasé when, a couple of years later, Lil' Louis said he wanted to put the record out. "He expressed how upset he was that people were ripping off the tune," says Jefferson. "He then released 'Video Clash' under his own name [with Jefferson's permission] and didn't give me or Kym song writing credits." The record—included on this album—was pressed up on Dance Mania in 1988. So at least the genesis of this particular record, and its manifold offshoots, is clear. Right?

* * * * *

In a short five years, Chicago house had more or less completed the first cycle of its story. The simple version of this narrative goes something l-l-l-like this. Having started out as a small town, organic art form that melded pragmatics, pleasure and creativity, house chiselled out a potentially lucrative market and, after that, was ransacked by moneymen. The drive to commercialism spawned sameness and fatigue, but it also helped generate new markets outside of Chicago that, in turn, spawned new waves of dynamism followed by plagiarism and fatigue.

The slightly more complicated version of house music's first half-decade, mindful that there can be no way back to the genre's earliest years, tells a different version of events. House music, according to this account, emerged in 1984 in an environment defined not by innocence and manic creativity but rather by ruthlessness and blandness. Two years of high creativity ensued (the departure of Saunders to the West Cost to pursue a recording career in R&B for Geffen may or may not have been a coincidence), and this inventiveness revolved around Hardy, who developed a frantically dynamic environment for artists and dancers alike. Some critics suggest that stagnation set in following the release of "Acid Tracks", but experimental tracks were still plentiful ¾ until a combination of government politics, excessive drug use drugs the greener concrete of other cities broke up the reigning artist-DJ-dancer nexus.

As Chicago started to splutter, Manchester, London, Paris and Rimini joined New York and New Jersey and flung themselves into house. (Detroit, and to a large extent Berlin, stuck to Techno.) Deep house emerged as a compelling counterpoint to acid—Jefferson was once again an important pioneer—before it mutated into a more general repudiation of progressive house or trance, which were the dominant sounds of Britain and Europe in the early 1990s. By the end of the decade deep house (alternatively known as Garage or New Jersey) had largely descended into a cul-de-sac of jaded, chin-stroking tracks and too-highly-polished vocals. In the meantime, techno and drum and bass forged their position at the head of radical experimentalism ¾ and confined house to the realm of safe nostalgia (even "Dad's music") in the process.

Meanwhile Chicago, having climbed so high so fast, experienced an attack of vertigo and lost its balance altogether. Its subsequent fall was bruising, but not fatal. Key producers and DJs moved away or, in the tragic case of Ron Hardy, passed away, and for a while the city's dance scene, which had partied hard for the best part of a decade, suffered from a nasty hangover. By the early 1990s, however, the Chicago dance scene started to rediscover its rhythm and a new generation of producers (including Cajmere, Roy Davis Jnr., Ron Trent, Glenn Underground, DJ Sneak, Anthony Nicholson, Paul Johnson, Boo Williams) and labels (such as Cajual, Prescription, Clairaudience, Relief and Clubhouse) made sure that Chicago didn't simply signify the past.

While many of the new scenesters looked to disco (for loop-friendly samples) and deep house (for mood-inducing instrumentation), others—most notably Cajmere and Davis—developed a dialogue with the tradition of acid house. Cajmere's "Explorer" (1994), included on this album, provides one example of this evolving avant-attitude. Davis's "Acid Bass" (1995), also featured here, stands as another. (Incidentally, "Acid Bass" more or less coincided the release of the "Gabrielle", another Davis track, which did so much to inspire UK Garage.) The inclusion of these records stands as a reminder Chicago didn't disappear from the house music map towards the end of the 1980s. The city's experimental foundations might have wobbled for a while, but by the mid-1990s they had been firmly re-established.

All quotes are from original interviews unless otherwise stated.

To download the article, click here.