In Julie Malnig ed. Ballroom, Boogie, Shimmy Sham, Shake: A Social and Popular Dance Reader.

The Saturday Night Fever publicity shot of a white-suited John Travolta, right hand pointing up and left hand, twisting along the same axis, aiming down, quickly became (and continues to be) the consciousness-invading icon of 1970s disco culture. The image evokes a strutting, straight masculinity. Tony Manero, played by Travolta, is a Hustle expert and a straight man on the prowl; in the photo, he is pictured alone, but his look and posture reveal that he is searching for a female partner, both on and off the dance floor. Released in November 1977, Saturday Night Fever ushered disco into the American mainstream, where it remained for a relatively short eighteen months. Travolta and 2001 Odyssey, the discotheque featured in the film, became the key reference points for dancers and club owners during disco's commercial peak.

Beyond the celluloid sheen and marketing paraphernalia of the post-Saturday Night Fever disco boom, however, the 1970s dance floor functioned as a threshold space in which dancers broke with the tradition of couples dancing and forged a new practice of solo club dancing. Although the shift in style suggested that individuality and loneliness came to dominate the floor, participants in fact discovered a new partner in the form of the dancing crowd. The Travolta-types may have subsequently gained a Gucci-shoed or stiletto-heeled foothold on the dance floor towards the end of the "disco decade," but their grip proved to be ephemeral in the post-disco era. From 1980 onwards, the solo dancer, moving to the collective rhythms of the room, formed the enduring model for contemporary club culture.

The sexual and bodily politics of Saturday Night Fever didn't appear out of thin air, of course. If dancing is an articulation of the wider world, reflecting dominant forces while providing a space for difference and resistance, the history of social dance in the United States has been intertwined with the shifting yet resilient practice of patriarchal heterosexuality. On the dance floor this has become manifest through the partnered couple, in which the man, assuming the role of gatekeeper, both invited his female partner onto the floor and then assumed the role of dance leader. Although the position of the male lead did not go unchallenged--the twentieth century is replete with examples of social dances in which the couple would break for periods on the floor or the woman would be granted periods of relative control within the couple--the framing role of the leading man remained in place.

Dances such as the Waltz and the Foxtrot, which allowed for minimal individual movement, were the most rigorously partnered of all, at least from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, and when couples in "modern" ballroom dancing developed their independence from the wider floor by developing their own "individuality," this served to entrench the heterosexual couple--now unique in their relationship--still further.[i] The rise of black social dance such as the Lindy Hop (often referred to as the Jitterbug) and the Texas Tommy chipped away at these practices inasmuch as they allowed partners to break away from each other and intersperse moves with individual improvisation. As Marshall and Jean Stearns, writing in 1968, noted, "both dances constitute a frame into which almost any movement can be inserted before the dancers return to each other."{C}[ii]{C} The Stearns added that, "while a Lindy team often danced together during the opening ensembles of a big band, they tended to go into a breakaway and improvise individual steps when the band arrangement led into a solo."[iii] These and other dances, such as the Charleston and the Black Bottom, integrated breakaway practices that enabled dancers (including, of course, female followers) to discover a new form of expressive freedom. The mutating tensions between the couple and the individual were, however, regularly resolved in favor of the former.

The unit of the couple faced its most sustained challenge when the Twist emerged alongside the first discotheques in New York City at the beginning of the 1960s.[iv] Allowing their bodies to respond to the affective space of the club, in which dancers encountered a combination of amplified sound and lighting effects, partners were couples only in name. Marshall and Jean Stearns acknowledged that the Twist and related dances had produced a "new and rhythmically sophisticated generation," but remained pessimistic about the environment in which the dancing occurred.[v] "No one could dance with finesse in such crowded darkness, even if he wished. . . The only way to attract attention was to go ape with more energy than skill, achieving a very disordered effect."{C}[vi]{C} Couples dancing (alternatively known as "hand dancing") all but imploded, yet the individual free-form style of the Twist appeared to be an inadequate replacement when, towards the end of the 1960s, the dance went out of fashion, the music industry stopped pushing the music, and beacon discotheques such as Arthur began to close.

Contemporary disco dancing emerged out of the dual context of African American social dance and the rise of the discotheque, and was propelled forward by the sudden influx of gay men into these social dance spaces at the beginning of the 1970s.[vii] Up until this moment, gay men were marginal within social dance, for while they were free to go out and dance, they weren't free to choose their partner. Although the door staff at flashbulb discotheques such as Arthur waived gay men to the front of the queue because of their ability to energize the dance floor, these men were still required by New York state law to take to the floor with female partners. The Stonewall Inn was one of the few venues in Manhattan where men could dance with other men, but patrons had to make do with the stuttering rhythms of a jukebox as well as regular police raids. By the time the owner of the Electric Circus, responding to the Stonewall rebellion of June 1969, invited gay men to share the dance floor with straights, the institution of the discotheque was in nose-dive decline.[viii] Because the Electric Circus was still marked as a straight (if tolerant) venue, the influx of gay men into the venue was minimal.

The key turning point in the culture of individual free-form dance arrived when, more or less simultaneously, David Mancuso began to put on regular parties in his Broadway loft apartment (which became known as the Loft) on Valentine's Day 1970, and two entrepreneurs known as Seymour and Shelley who owned a series of gay bars in the West Village took over a struggling straight discotheque called the Sanctuary and encouraged their clientele to give it a go. Both venues were unique in that gay men--who required "special protection" until Mayor Lindsay repealed New York City's laws governing the admission of gay men to cabarets, dance halls, and restaurants in October 1971--were dominant on the floor (even if straights were present) and the energy and expressivity of these dancers, many of whom faced the double marginalization of being black as well as gay, kick-started 1970s dance culture.[ix] A series of legendary private parties (including Flamingo, the Gallery, the Paradise Garage, Reade Street, the SoHo Place and the Tenth Floor) emerged out of this moment, while the public institution of the discotheque also received a second lease of life that culminated in the opening of Studio 54 in 1977.

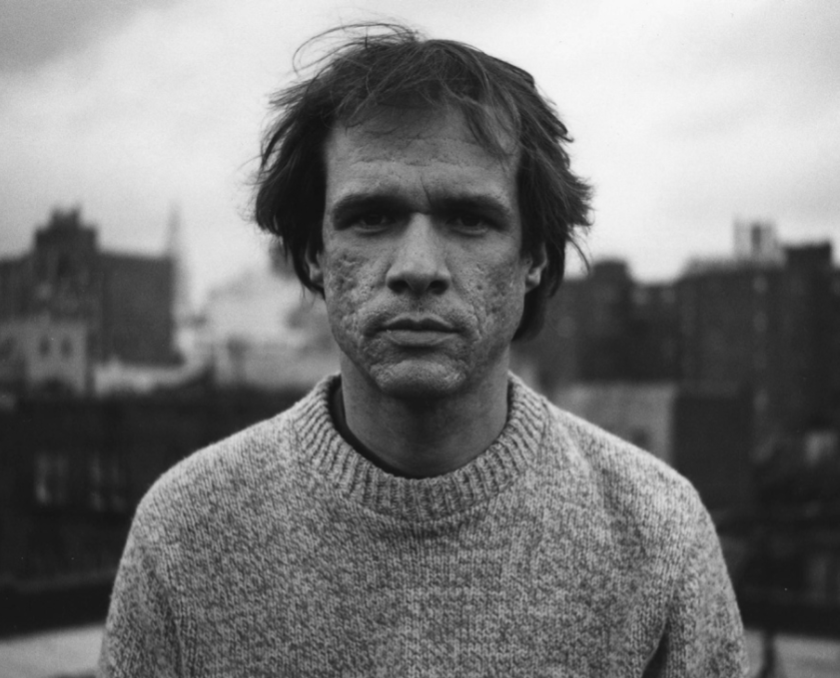

According to eyewitness such as spinner Francis Grasso, who surveyed the metamorphosis of the crowd at the Sanctuary from the vantage point of his DJ booth, the difference in dance styles was radical. "[Seymour and Shelley's] opening night was a bang," he told me. "I'd never seen a crowd party like that before. . . When the Sanctuary went gay I didn't play that many slow records because they were drinkers and they knew how to party. Just the sheer heat and numbers made them drink. The energy level was phenomenal."[x] That energy was founded on the newness of the experience (this was the first time that gay men had been able to dance together in a dedicated dance venue) and the wider social context (the celebratory momentum of gay liberation).

Whereas couples had dominated the straight Sanctuary, the gay reincarnation was organized around individual dancers who took to the floor by themselves. The break with partnered dancing wasn't total--men would sometimes grab each other before dancing, or sidle up to each other on the floor--but the established matrix of social dance was nevertheless loosened to the point where it was no longer recognizable. Yet the shift towards individual free-form dancing, which was mirrored at the Loft, didn't result in participants experiencing the floor as space of isolation. Instead, by moving around on a single spot, dancers would effectively groove with multiple "partners." "You could be on the dance floor and the most beautiful woman that you had ever seen in your life would come and dance right on top of you," Frankie Knuckles, a regular at the Loft, told me. "Then the minute you turned around a man that looked just as good would do the same thing. Or you would be sandwiched between the two of them, or between two women, or between two men, and you would feel completely comfortable."[xi] The experience of dancing with scores of other dancers helped generate the notion of the dancing "crowd" as a unified and powerful organism. By moving to the rhythm of the DJ and the gyrating bodies that surrounded them, gay men realized they were part of a collective movement. The idea of dancing with a partner didn't so much implode as expand.

Early discotheque dancers, according to participants such as Frank Crapanzano and Jorge La Torre (two regulars at Manhattan's best known gay venues), didn't develop a defined style, such as the Twist, but instead improvised their steps (moving backwards and forwards, then side to side, etc.) and, in line with black jazz dance and the Twist, generated movement from their hips. Combining grace and stamina, the dancers broke with the dominant practices of the late 1960s. "The dancing was very jazz-spirited," Danny Krivit, an early downtown dance aficionado whose father ran a popular gay bar in the Village called the Ninth Circle, told me. "It was just free. Before the Loft people thought they were free but they were just jerking around and jumping up and down."[xii]

Dance floors were usually crowded, often to sardine-like proportions at hipper-than-thou venues such as the Loft, the Tenth Floor, and the Gallery, so there was little room to show off special steps, or form circles around especially skilled dancers. Some dancers would seek out unpopulated areas--Archie Burnett, a "Loft baby" from the late 1970s onwards, told me how he would gravitate towards the cloak room, away from the main floor, in order to find space to work on (and show off) his steps. But the lack of space was of little concern to most protagonists, whose aim was to participate in a musical-kinetic form of individual dissolution and collective bliss.[xiii] While the exhibition (or novelty) practices of the swing era involved, in the words of Jonathan David Jackson, "asserting such a pronounced sense of personal style that the black vernacular dancer's actions invite a charged, voyeuristic attention from the community at the ritual event," the party-goers of the early 1970s expressed their individuality within a more overtly participatory, less visible framework.[xiv]

Drugs--in particular LSD and marijuana, although Quaaludes, poppers and speed also became popular as the decade progressed--contributed to the hedonistic quality of the dance floor experience, although New York's downtown venues were ultimately grounded in a collective rather than individualistic notion of pleasure. As La Torre told me, the consumption of drugs was an enabling add-on part of the dance experience, which was ultimately focused on tribal transcendence rather than a narrower, individualistic high.[xv] Describing the experience in similar terms, Jim Feldman, a dancer at the Paradise Garage (an expanded version of the Loft that opened in 1977), noted, "There was a sexual undercurrent at the Garage but no one was picking up. Sex was subsumed to the music and was worked out in the dancing. It was like having sex with everyone. It was very unifying."[xvi] As Maria Pini, in an analysis of club and rave culture in the 1990s that speaks to the 1970s, comments: "This is not about a sexual longing directed towards a specific or individual `target,' but about a far more dispersed and fragmented set of erotic energies which appear to be generated within the dance event."[xvii]

Contrary to some accounts of the early disco scene, out of which certain mythologies continue to circulate, sex rarely, if ever, took place on the dance floors of New York's downtown discotheques.[xviii] Although the evocation of sex is not altogether ridiculous--a sexual energy undoubtedly permeated the early gay discotheques, and erotic glances would regularly be exchanged--dancing at the Sanctuary, the Loft, and scores of other venues wasn't the first stage in the process of seduction. Revelers refigured the dance floor not as a site of foreplay--the contention of David Walsh in "Saturday Night Fever: An Ethnography of Disco Dancing"--but of spiritual communion where sensation wasn't confined to the genitals but materialized in every new touch, sound, sight, and smell.[xix] "The Loft chipped away at the ritual of sex as the driving force behind parties," Mark Riley, a confident of Mancuso, explained. "Dance was not a means to sex but drove the space."[xx] The ethos continues to this day, even if the club scene is now dominated by house rather than disco music. As Sally R. Sommer comments in "C'mon to my house": Underground-House Dancing (in this collection), "the redemption of total body sensuality without rampant sexuality fostered by hard dancing that engages the body and mind" remains central to the paradigm of the contemporary underground dance network in New York and beyond.[xxi]

The technologies of amplified sound and lighting developed at an exponential pace during the 1970s and, combining with rhythm-driven dance music and perception-enhancing drugs, established a hyper-affective environment that prioritized alternative forms of bodily sensation. Mancuso introduced the technologies of tweeter arrays (clusters of small loudspeakers, which emit high-end frequencies, positioned above the floor) and bass reinforcements (additional sets of subwoofers positioned at ground level) at the start of the 1970s in order to boost the treble and bass at opportune moments, and by the end of the decade sound engineers such as Richard Long had multiplied the effects of these innovations in venues such as the Garage. "Bass-heavy dance music provokes the recognition that we do not just `hear' with our ears, but with our entire body," write Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson, in Discographies. "This embodiment is achieved through the experiential characteristics, the kinesthetic effects of the disco, the club, the dance floor, and the performative and reproductive technologies employed within them."[xxii]

The spread of the marathon dance session in the 1970s discotheque heightened this affective experience and was particularly pronounced at private venues such as the Loft, the Tenth Floor, the Gallery, Flamingo, 12 West, and the Garage, where the owners bypassed cabaret licensing laws by offering only non-alcoholic drinks and running a private membership system. That meant that they could stay open as long as they liked--in contrast to public venues that operated under New York's cabaret licensing laws. Mancuso started off with the seemingly audacious decision to open until 6:00 a.m.; by the early 1980s he was holding parties that would begin at midnight and carry on until 8p.m. the following evening. The substitution of alcohol with energy-enhancing drugs enabled dancers to stay on the floor for longer and longer periods of time, and this in turn encouraged them to "lose themselves" in the dance experience. While the idea of engaging in a trance-inducing workout might not have been new--shamanistic ceremonies and drag balls functioned according to similar principles--it was a novel experience within the context of late 1960s-early 1970s North American society, and it was novel in terms of its deployment of amplified sound and disorienting light.

The sheer length of these marathon dance sessions, the reduced consumption of alcohol, and the relatively abrupt end to the practice of partnered dancing combined to create the conditions for the emergence of a new narrative of dance. Instead of regarding the night as a series of ventures onto the floor that would be interspersed by visits to the bar or leaving the floor to find a new partner, dancers started to stay on the floor for hours on end, and DJs started to sculpt a soundtrack to respond to these new conditions. Whereas 1960s discotheque DJs would build to a quick peak and then introduce a slow record to "work the bar" or "move the floor around," spinners such as Grasso and, above all, Mancuso, began to build sets that would tell a story over an entire night, beginning gently before climaxing with a series of peaks, after which the spinner would bring the dancers down.

The DJ was central to the ritual of 1970s dance culture, but the dancing crowd was no less important, and it was the combination of these two elements that created the conditions for the dance floor dynamic. A good DJ didn't only lead dancers along his or her (male spinners far outnumbered their female counterparts) preferred musical path, but would also feel the mood of the dance floor and select records according to this energy (which could be communicated by the vigor of the dancing, or level of the crowd's screams, or sign language of dancers directed towards the booth). This communication--described by Sarah Thornton, in her early analysis of late 1980s and 1990s dance culture, as "the vibe"--amounted to a form of synergistic music-making in which separate elements combined to create a mutually beneficial and greater whole.[xxiii]

Continuous with the practice of antiphony, or the call-and-response of African American gospel, the DJ-crowd exchange can be traced to the 1960s discotheque, but the best-known spinner of that era, Terry Noël, nevertheless preferred to view himself as a puppeteer who asserted his will over an obedient, passive floor.[xxiv] The tempo of Twist music, which was significantly more uniform than the "party music" selected by DJs in the early 1970s, would have dampened dancer expectations of influencing a spinner's selections, and couples' dancing, inasmuch as it was still in play in the 1960s, would have further discouraged dancers from making the DJ their primary focus for communication. It was only when the unit of the couple was further weakened in the early 1970s that the wider crowd, conceived of as a communicative force, discovered its power to influence the course of a night.

The popularization of this call-and-response pattern, so familiar within gospel, on the dance floor points to the way in which the dance experience of the 1970s was experienced as a spiritual affair, albeit within a secular-to-the-point-of-sacrilegious context. This quality was apparent at the Sanctuary, which was situated in a converted church in which the DJ booth was housed in the pulpit. La Torre argues that the spiritual dimension of the dance floor experience became particularly pronounced in the second half of the 1970s when the music became less vocally driven and more instrumental, thereby allowing the mind to wander more freely. All of this anticipates Kai Fikentscher's description of the nightclub's parallels with the African American church: both the African American church and the nightclub "feature ritualized activities centered around music, dance, and worship, in which there are no set boundaries between secular and sacred domains," and this tradition cultivated a mood of group ecstasy and catharsis on the dance floors of the Loft, the Gallery, the SoHo Place, Reade Street, the Warehouse, and the early incarnation of the Paradise Garage.[xxv]

The nature of the ecstatic-cathartic experience of the 1970s discotheque can be theorized in various ways. Freud's discussion of pre-Oedipal sexuality--which he characterizes as the polymorphous perverse, whereby the child experiences sexual drives that are organized around not the genitals but the entire body--is appealing when analyzing the Loft, which evoked a series of child-oriented themes in its mass deployment of party balloons and, thanks to its "safe" private party status, encouraged dancers to "regress" into a series of pre-linguistic yelps, gasps, and screeches. These themes were played out in the 1970s and beyond: baggy, sexless t-shirts were symbolic of late 1980s club culture in the U.K.; dummies and other kids' accessories, as well as intentionally inane kid-style melodic riffs, were ubiquitous within the Anglo-American Rave scene of the 1990s.[xxvi] Of course these parties didn't enable a literal return to a pre-Oedipal childhood, but they did establish the conditions for the rediscovery of something that is experienced (if temporarily forgotten) in childhood. Dancing in a constricted space in which the boundaried body was lost in a pre-linguistic sea of touch and sensation, participants experienced subjectivity in a non-egotistic mode--which suggests that the theory of the polymorphous perverse might be more than an evocative metaphor.

Describing one of his trips to Flamingo, author Edmund White evokes the process of abandoning his cherished ego. "I am ordinarily squeamish about touching an alien body," he wrote in States Of Desire: Travels in Gay America. "I loathe crowds. But tonight the drugs and the music and the exhilaration had stripped me of all such scruples. We were packed in so tightly we were forced to slither across each other's wet bodies and arms; I felt my arm moving like a piston in synchrony against a stranger's--and I did not pull away. Freed of my shirt and my touchiness, I surrendered myself to the idea that I was just like everyone else. A body among bodies."[xxvii] Unable to avoid physical contact on all sides, dancers had little choice but to dissolve into the amorphous whole and, as the distinctions between self and other collapsed, they relinquished their socialized desire for independence and separation.

Developing a related argument, cultural critic Walter Hughes describes the way in which the boundaried masculine body, having been penetrated sonically on the dance floor, loses its autonomy and, in turn, establishes an empathetic alliance with the repressed-yet-resistant figure of the black female diva. Disciplined by the relentless disco beat, which compels him to move, the gay male dancer embraces the traditional role of slave while experimenting with a cyborg-like refusal of the "natural," his body no longer being an autonomous entity but instead a mixture of tissue, bone, and reverberating sound.[xxviii] The emergence of Euro-disco, which isolated and reinforced the four-on-the-floor bass beat of disco and combined this rigid rhythm with the nascent synthesizer technology of the 1970s, accentuated the experience of the dance floor as a realm in which technology went hand-in-hand with disciplinary compulsion.

At the same time, dancers also experienced disco as polyrhythmic, especially in contrast to thudding pulse of contemporary rock, which had long since departed from the rhythmic interplay of rock 'n' roll, and this quality underpinned Richard Dyer's compelling defense of disco, published in 1979.[xxix] Whereas rock, according to Dyer, confined "sexuality to the cock" and was thus "indelibly phallo-centric music," disco "restores eroticism to the whole body" thanks to its "willingness to play with rhythm," and it does this "for both sexes."[xxx] Gilbert and Pearson, drawing on Dyer's argument, add: "If the body in its very materiality is an effect of repeated practices of which the experience of music is one, then we can say that what a music like disco can offer is a mode of actually rematerializing the body in terms which confound the gender binary."[xxxi]

The centrality of this experiential process--of abandoning the ego and giving oneself up to the undulating rhythms and affective sensations of the dance floor--helps explain why gay men, along with people of color and women, were so central to disco's earliest formation. Having been historically excluded from the Enlightenment project, these groups were less attached to the project of bourgeois individualism and rational advancement than their straight white male counterparts, and were accordingly more open to the disturbing forces of sonic-dance rapture. Riding on the back of gay liberation, feminism, and civil rights, the core dancers of the disco era were also engaging in the development of new social forms and cultural expressions, and the floor provided them with a relatively safe space in which they could work out their concerns and articulate their emotions and desires.

The discotheque, however, didn't only function as a meeting space for the outcastes of the rainbow coalition. Straight men were involved in discotheque culture from the outset, both in its 1960s (predominantly straight commercial) and 1970s (predominantly gay subterranean) guises. While straights were relatively marginal in spaces such as the Loft and the Sanctuary, they became more prominent after club culture became more visible (especially through the commercial success of venues such as Le Jardin, which was situated in Times Square) and the media began to report on the phenomenon. Their participation became even more pronounced when the mid-1970s recession provided straight white men with one of disco's most important pretexts: the need for release. "Straight, middle-class people never learned how to party," a gay Puerto Rican partygoer told the New York Sunday News in 1975. "To them, a party is where you get all dressed up just to stand around with a drink in your hand, talking business. But for us, partying is release, celebration. The more hostile the vibes in your life, the better you learn how to party, 'cause that's your salvation. Now that things aren't going so well for the stockbroker in Westchester and his wife, they come down here, where it doesn't matter how much money you make, or what the label in your coat says."[xxxii]

The broad characteristics of the early 1970s dance floor--a crowd largely composed of outsider groups that would dance as individuals-in-the-crowd in a highly affective environment for an extended period of time in--could be found not only at private venues such as the Loft, the Tenth Floor, the Gallery, and so on, but also at public venues such as the Limelight (the Greenwich Village version), the Haven, Le Jardin, and Galaxy 21 (Figure 11.1). Whereas the private parties were normally considered underground and the public venues commercial, the key difference between the two was social rather than aesthetic. Hardcore dancers would frequent both, but whereas their position would be protected in the private parties, which weren't advertised and weren't open to members of the public, they were vulnerable to "unknowing outsiders" in public venues. As such the dance ritual practiced at the Sanctuary, the Limelight, Le Jardin, and other public venues would be every bit as purist as that practiced in counterpart private parties at the beginning of their run, but their purism was invariably short-lived, at least in comparison to the private venues.

Even so, the private party network, which referred to itself as "the underground," could hardly be described as constituting a hermetically sealed entity. These private parties influenced the mainstream by generating chart hits, and underground DJs were insistent that they received Gold Records, or at least free records (via the first Record Pools), in return for their service to the music industry. In addition, DJs were largely committed to spreading their music beyond their core dance crowd, with figures such as Nicky Siano playing at his own private party, the Gallery, as well as highly visible venues such as Studio 54.

The precariousness of the private party network's model of dancing was illustrated in the second half of the decade when it was twisted to the point of non-recognition. As discotheque culture entered the commercial mainstream, DJs started to push primarily chart-based music and, on the dance floor, the Hustle (as well as various line dances) came to dominate. Critics such as William Safire, the conservative New York Times op ed columnist, were delighted and praised the routine for marking a conservative return to self-discipline, responsibility, and communication after a fifteen-year period of "frantic self-expression" and "personal isolationism" on the dance floor. "The political fact is that the absolute-freedom days of the dance are over," added Safire. "When you are committed to considering what your partner will do next, and must signal your own intentions so that the `team' of which you are a part can stay in step, then you have embraced not only a dance partner, but responsibility."[xxxiii]

Drawn from the Mambo, the Hustle required partners to hold hands while one led the other in a series of learned step and spin sequences and, popularized by Van McCoy's hit single, the practice subsequently emerged as a conspicuous ingredient of the discotheque revival to the extent that it was the featured dance of Saturday Night Fever, the film that became the key catalyst within disco's belated and, ultimately, short-lived explosion. That film, in which there is no discernable dynamic between the selections of the DJ or the movements of Manero and his co-dancers, became the takeoff point for the mass crossover in disco during 1978 and the template for the disco boom.

Music writer Peter Shapiro confirms that the "Hustle marked the return of dancing as a surrogate for, or prelude to, sex," yet he also maintains that "as long as you strutted your stuff on the floor, disco was essentially democratic."[xxxiv] It is difficult, however, to see how the Hustle could have maintained the individual-within-the-crowd dynamic that was so central to the early (and, ultimately, enduring) formation of disco. For sure, Hustle dancers could be expressive, but the Mambo-derived move disrupted the synergistic line of communication that was so central to the dance dynamic established in the early 1970s. Significantly, the move wasn't practiced in any of New York's hardcore venues.

Following the release of Saturday Night Fever, some thirty instruction books were published on disco dancing, and their focus on the Hustle, combined with the rapid growth of Hustle classes, is indicative of the way in which the priorities of New York's downtown dancers were lost in the second half of the 1970s. It is no coincidence that the DJ in Saturday Night Fever, Monty Rock, is an almost wholly absent figure. Spinners such as Paul Casella, who played in a variety of venues during the 1970s, testify that it was far easier to establish a flow in a hardcore urban setting than any commercial (urban or suburban) equivalent.

Dancing, of course, could be enjoyed outside of the esoteric ambience of the private party network and, for the most part, suburban clubbers, gravitating to local and urban venues, wouldn't have even been aware of what they were missing. In some instances, they might not have missed much: strong DJs were in operation outside of New York's hallowed downtown scene, and the Hustle was, ultimately, just one of a number of dance styles that were popularized in the 1970s (even if a number of the other routines also disrupted the line of communication between the floor and the booth). Of course, there is no reason to think that Hustle dancers were having a bad time, and while dance floor aficionados might have maintained that transcendence could only be attained through other moves, the producers of Saturday Night Fever were clever enough to capitalize on the potential pleasure of this particular dance practice. In the process they generated a new vehicle for the popularization of social dance in the United States.

Saturday Night Fever was initially welcomed by a number of disco purists, but the excitement soon waned. The extraordinary commercial success of the film might have encouraged the rapid expansion of the discotheque sector, but the new strata of club owners tended to create third-rate venues in their rush to capitalize on the boom. Inadequate sound systems broke up when pumped hard, illuminated floors flashed out their distracting sequences, and a new generation of know-nothing DJ automatons spurred an aural diet of prescribed, shrill white pop. Meanwhile male dancers took to dressing, dancing, and generally behaving like John Travolta, and their come-and-get-me gestures soon began to look ridiculous to even the least discerning dancer.

The rapid dilution of the downtown dance dynamic during the course of 1978, with the glut of bad disco music that was released in the slipstream of Saturday Night Fever, and the fatigue that inevitably followed the film's marathon stint at the top established the conditions for national backlash against disco. The culture's demise was accelerated by the combination of a deep recession in 1979 and the gathering momentum of the "disco sucks movement," a coalition of predominantly straight white men who felt dispossessed by disco and vented their anger and revenge in frequently homophobic and, to a lesser extent, racist publicity stunts. Yet while hardcore DJs and dance aficionados blanched at the discourse of "disco sucks," they passively agreed with the premise that disco productions in the post-Saturday Night Fever climate had become, for the most part, aesthetically banal and tiresomely commercial.

The Hustle didn't survive the so-called "death of disco," at least not as the standard routine on club dance floors of the United States during the 1980s and beyond, but the dance practices of the downtown party did. The outward signs suggested a culture in terminal decline--thousands of clubs, many of them in suburban centers, closed in the second half of 1979, and at the beginning of 1980 the music majors ditched the word "disco" and replaced it with "dance"--but parties such as the Loft, the Garage, and the Warehouse in Chicago, as well as host of new, groundbreaking venues such as Danceteria, the Saint, Bond's, and the Funhouse went from strength to strength. Dance floor practices in the key urban venues of the 1980s and beyond were largely continuous with those of the early 1970s, and, as described by Fikentscher and Sommer, this template has survived into contemporary North American club culture, which largely revolves around the more electronically-driven genres of house, techno, and garage. As such, the dance formations of the New York downtown party network of the early 1970s have proved to be significantly more enduring than the Hustle, even though disco culture will, it seems, forever be associated with this altogether safer routine.

Notes

Many thanks to Julie Malnig for the astute comments she offered throughout the writing of this essay.

[i] Elsewhere in this collection Elizabeth Aldrich points out that from the middle of the eighteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century the Waltz revolved around "whirling pivots" and, as such, could be practiced without a leader.

[ii] Marshall and Jean Stearns, Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994), 323.

[iii] Ibid., 325.

[iv] Ibid., 361.

[v] Ibid., 7.

[vi] Ibid., 5.

[vii] My book, Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-79 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004), opens at the start of the 1970s and investigates, amongst other things, the precise chronology of the evolution of 1970s club culture. A number of points that I make in this article are drawn from the book.

[viii] Charles Kaiser, The Gay Metropolis 1940-1996 (London: Phoenix, 1999), 201-2.

[ix] See Love Saves the Day, 28-30, for a more detailed discussion of the relationship between the Stonewall rebellion, gay liberation and the rise of gay discotheque culture. In contrast to a number of authors, I argue that disco didn't so much grow out of the Stonewall rebellion as run parallel to it as part of a wider movement of gay activism, consciousness, and culture.

[x] Lawrence, Love Saves the Day, 21, 37-38.

[xi] Ibid., 25.

[xii] Ibid., 26.

[xiii] Ibid., 25; Archie Burnett, interview with author, 19 September 1997.

[xiv] Jonathan David Jackson, "Improvisation in African-American Vernacular Dancing," Dance Research Journal 33 (2001/02): 45-46.

[xv] Lawrence, Love Saves the Day, 288-89.

[xvi] Ibid., 353.

[xvii] Maria Pini, Club Cultures and Female Subjectivity: The Move from Home to House (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001), 165.

[xviii] For example, Albert Goldman's Disco, for long the most authoritative account of 1970s American discotheque culture, describes orgiastic scenes taking place at the Sanctuary (London: Hawthorn Books, 1978), 118-119. This claim, for which (after interviewing several regulars at the venue) I have found no supporting evidence, is regularly repeated in books on club culture including, most recently, Peter Shapiro, Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 15.

[xix] David Walsh, "`Saturday Night Fever': An Ethnography of Disco Dancing," in Helen Thomas ed., Dance, Gender and Culture (London: Macmillan, 1993), 116.

[xx] Lawrence, Love Saves the Day, 25.

[xxi] Sommer, "C'mon to my house," in Julie Malnig, ed., The Social and Popular Dance Reader (University of Illinois Press, 2007), pg. Sally Sommer, "C'mon to My House: Underground-House Dancing", Dance Research Journal, 2001/02, 33, 74, reprinted in Julie Malnig, ed., The Social and Popular Dance Reader (University of Illinois Press, 2007), pg. House music dates back to 1980 or 1981, when dancers at the Warehouse in Chicago started to describe the DJ's selections -- disco, boogie and some early Italo disco -- as "house music", house in this instance being an abbreviation of the Warehouse (Lawrence, 2004, 409-10). In late 1983 young Chicago producers started to use cheap synthesiser and drum machine technology to create their own dance tracks, which imitated a number of disco's bass lines and rhythmic patterns, and in 1984 the term house music was reappointed to designate Chicago's electronic offshoot of disco. The new genre started to receive play in New York clubs in 1985. Sally Sommer's use of the term house music is more general than my own, and her use of the term house dancing is used interchangeably with the style of dancing at the Loft, which she calls Lofting (and which I label individual free-form dance).

[xxii] Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson, Discographies: Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound (London and New York: 1999), 134.

[xxiii] Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital (Hanover, New Hampshire: Wesleyan University Press, 1996), 29.

[xxiv] Philip H. Dougherty, "Now the Latest Craze Is 1-2-3, All Fall Down," New York Times, 11 February 1965.

[xxv] Kai Fikentscher, You Better Work! Underground Dance Music in New York City (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press), 101.

[xxvi] See, for example, Hillegonda Rietveld, "Living the Dream," in Steve Redhead ed., Rave Off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture (Aldershot: Avebury, 1993), 54.

[xxvii] Edmund White, States Of Desire: Travels in Gay America (London: Picador, 1986), 270-271.

[xxviii] Walter Hughes, "In the Empire of the Beat: Discipline and Disco," in Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose eds., Microphone Fiends: Youth Music & Youth Culture (New York and London: Routledge, 1994), 151-152.

[xxix] Richard Dyer, "In Defence of Disco," Gay Left, summer 1979. Reprinted in Hanif Kureishi and Jon Savage eds., The Faber Book of Pop (London, Boston: Faber and Faber, 1995), 518-27.

[xxx] Ibid., 523.

[xxxi] Gilbert and Pearson, Discographies, 102.

[xxxii] Sheila Weller, "The New Wave of Discotheques," New York Sunday News, 31 August 1975.

[xxxiii] William Safire, "On the Hustle," New York Times, 4 August 1975.

[xxxiv] Shapiro, Turn the Beat Around, 184-85.

Download the article here.