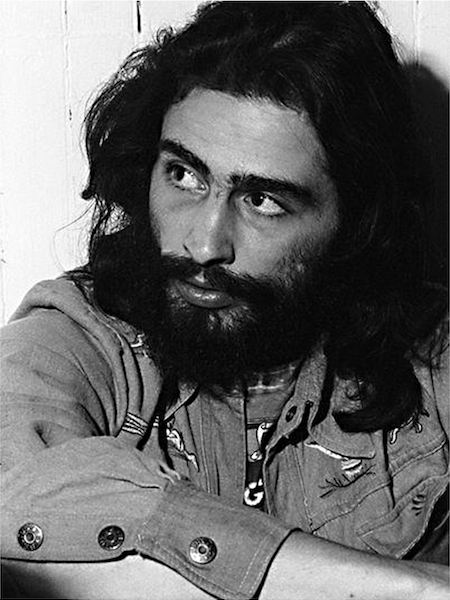

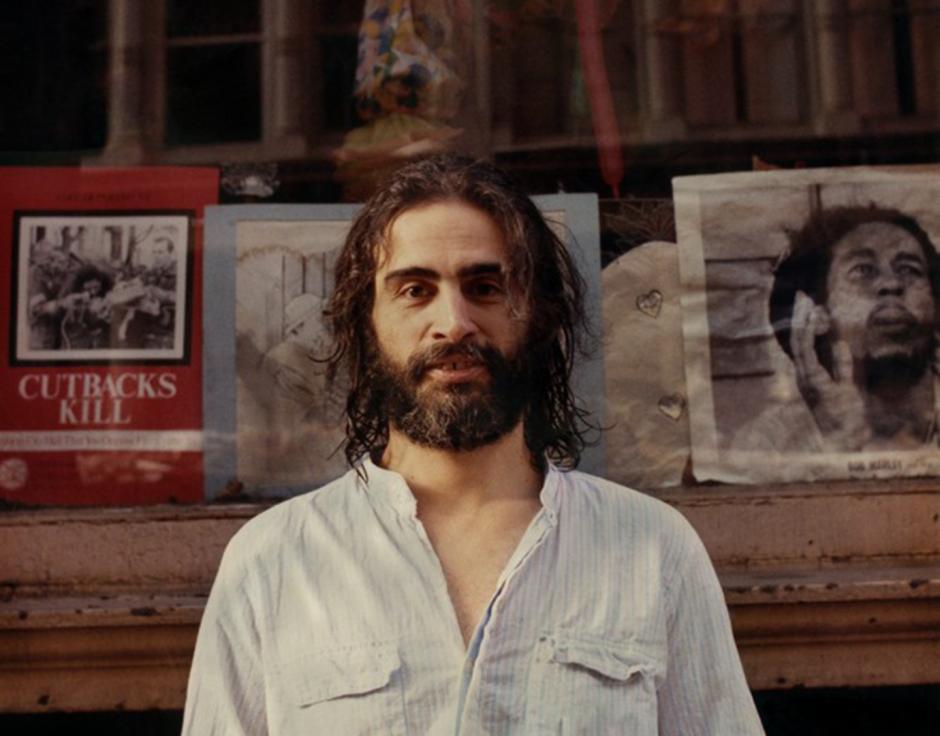

David Mancuso outside Prince Street Loft, New York, 1988. Photo by Pat Bates

When David Mancuso passed away on November 14, 2016, he left behind a legacy that enjoys no obvious precedent. Celebrating the Loft’s 46th anniversary this past February, he oversaw what must surely be the longest-running party in the United States’shistory—and perhaps even the world’s—having hit upon the right combination the night he staged a “Love Saves the Day” Valentine’s party in his downtown home in 1970 and initiated Loft-style parties in Japan and London 16 and 13 years ago, respectively. With all three manifestations rooted in friendship, inclusivity, community, participation, and collective transformation, the host has secured the life-after-death future of the party while demonstrating the effectiveness of a simple vision, the purity of which he never knowingly compromised. In this manner, the Loft has come to offer consistent light to a darkening terrain.

In one of the numerous interviews I conducted with David, I once asked him to explain how he would advise a newcomer to start a party. First, he replied, it’s necessary to have a group of friends that want to get together and dance, because without that there’s no basis for the party. Second, the friends need to find a room that has good acoustics and is comfortable for dancing, which means it should have rectangular dimensions, a reasonably high ceiling, a nice wooden floor, and a level of privacy that will enable people to relax. Next, the friends should piece together a simple, clean, and warm sound system that can be played at around 100 dB (so that people’s ears don’t become tired or even damaged). After that, the friends should decorate the room with balloons and a mirror ball, offering a cheap and timeless solution. They should also plan to prepare a spread of healthy food in case dancers become hungry during the course of the night. Finally—and as far as David was concerned, this was really the last thing to put in place—the friends should think of someone to select records that those gathered would want to dance to. Ultimately there could be no room for egos, including his own, if the party was to reach its communal potential.

Also rooted in friendship and the desire to party with freedom in a comfortable, private space, the Loft—as David’s guests came to name the party after it had been running for a few months—didn’t amount to an original moment so much as it pointed to a time when a number of practices, some of them decades’s old, came together in a new combination. The children’s home where David was taken days after his birth imbued him with the idea that families could be extended yet intimate, unified yet different, and precarious yet strong. Sister Alicia, who took care of him, put on a party whenever she was able to, and even went out to buy vinyl to make sure the kids were musically fed. The psychedelic guru Timothy Leary, who invited David to his house parties and popularized a philosophy around the psychedelic experience that would inform the way records came to be selected at the Loft, also became a power echo in David’s party scenario. Co-existing with Leary, the civil rights, gay liberation, feminist, and the anti-war movements came to manifest themselves in the egalitarian, rainbow coalition, come-as-you-are ethos of the Loft. And the Harlem rent parties of the 20s, in which working-class African Americans put on shindigs in order to raise money to pay the rent, established a template for putting on an intimate private party that could bypass the restrictions of New York City’s widely loathed cabaret licensing regulations. These streams travelled in different directions until February 14, 1970—when they met at 647 Broadway.

The homemade invitations for the February party carried the line “Love Saves the Day.” A short three years after the release of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” the coded promise of acid-inspired things to come swapped The Beatles’ gobbledygook with a declaration of universal love. The invitations also reproduced an image of Salvador Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory,” which suggested not Sister Alicia nor the children’s home—because David had yet to have his latent memories jogged into revelation—but instead, the chance to escape violence and oppression by entering into a different temporal dimension in which everyone could leave behind their socialised selves and dance until dawn. “Once you walked into the Loft, you were cut off from the outside world,” explained David. “You got into a timeless, mindless state. There was actually a clock in the back room but it only had one hand. It was made out of wood and after a short while it stopped working.”

When David’s guests left the Valentine’s Day party, they let him know that they wanted him to put on another one soon, and within a matter of months the shindigs had become a weekly affair. Inasmuch as anyone knew about them—and few did, because David didn’t advertise his parties, because they were private—they acquired a reputation for being ultra hip, in part because 647 Broadway was situated in the ex-manufacturing district of downtown New York, where nobody but a handful of artists and bohemians had thought about living. The artists (and David) moved in, because the district’s old warehouses offered a spectacular space in which to live as well as put on parties, and the inconvenience of having to have one’s kitchen, bedroom, and bathroom hidden from view (in order to avoid the punitive eyes of the city’s building inspectors) turned out to be a nice way to free up space in order to do things that weren’t related to cooking, sleeping, and washing. Outside, the frisson of transgression was heightened by the fact that there was no street lighting to illuminate the cobbled streets, and because David didn’t serve alcohol, he was able to keep his parties going until midday (and sometimes later), long after the city’s bars and discotheques had closed for the night. “Because I lived in a loft building, people started to say that they were going to the Loft,” remembered David. “It’s a given name and is sacred.”

From the beginning, David constantly sought to improve his sound system, convinced that this would result in a more musical and therefore a more socially transformative party experience. Having begun to invest in audiophile technology, he asked sound engineers to help him build gear, including tweeter arrays and bass reinforcements, so that he could tweak the sound during the course of a party, sending extra shivers down the spines of his guests. Yet by the time the technology had come to dominate discotheque sound, David had concluded that such add-ons were unnecessary with an audiophile set-up and instead headed deeper into the world of esoteric stereo equipment, adding Mark Levinson amplifiers and handcrafted Koetsu cartridges to a set-up that also featured Klipschorn speakers. “I had the tweeters installed to put highs into records that were too muddy but they turned into a monster,” David once said to me. “It was done out of ignorance. I wasn’t aware of Class-A sound, where the sound is more open and everything comes out.”

As David relentlessly fine-tuned his set-up, the energy at his parties became more free flowing and intense. “You could be on the dance floor and the most beautiful woman that you had ever seen in your life would come and dance right on top of you,” Frankie Knuckles, a regular at the Broadway Loft, once commented in an interview. “Then the minute you turned around, a man that looked just as good would do the same thing. Or you would be sandwiched between the two of them, or between two women, or between two men, and you would feel completely comfortable.” Facilitating a sonic trail that was generated by everyone in the room, David would pick out long, twisting tracks such as Eddie Kendricks’s “Girl, You Need A Change of Mind” and War’s “City, Country, City,” gutsy, political songs like The Equals’s “Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys” and Willie Hutch’s “Brother’s Gonna Work It Out,” uplifting, joyful anthems such as Dorothy Morrison’s “Rain” and MSFB’s “Love Is the Message,” and earthy, funky recordings that included James Brown’s “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” and Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa.” Positive, emotional, and transcendental, these and other songs touched the soul and helped forge a community.

The influence of the Loft spread far and wide. At the end of 1972, a Broadway regular opened the Tenth Floor as a Loft-style party for an exclusive, white gay clientele, which in turn led to the opening of Flamingo, which went on to become the most influential venue in the white gay scene. Objecting to the elitist nature of Flamingo’s self-anointed “A-list” dancers, another Loft regular founded 12 West with the idea of creating a more laidback party environment for white gay men. Meanwhile Nicky Siano, another Loft regular, launched his own Loft-style venue called the Gallery that mimicked David’s invitation system, hired his sound engineer, and even borrowed a fair chunk of his crowd when he shut down his party for the summer of 1973. The Soho Place (set up by Richard Long and Mike Stone) and Reade Street (established by Michael Brody) also drew heavily on David’s template. When both of those parties were forced to close, Brody resolved to open the Paradise Garage as an “expanded version of the Loft” and invited Long, considered by many to be New York’s premier sound engineer, to build the sound system. Meanwhile Robert Williams, another Loft regular, opened the Warehouse as yet another Loft-style venue after moving to Chicago. Heading to the Loft, where they danced and bonded, Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles went on to become the path breaking DJs at the Garage and the Warehouse, where they forged the outlines of what would later be called garage and house music. Other influential dance figures, including Tony Humphries, François Kevorkian, and David Morales, would look back on the Loft as an inspirational party. In short, the Loft was an incubator.

Like any party host, David had to face some unexpected hitches during his party’s 46-year run. In June of 1974, he moved to 99 Prince Street after city regulators pressured him into leaving his Broadway home. Ten years later, he bought a promising building in Alphabet City, only to see the neighbourhood slide into a virtual civil war. By the time he was forced to vacate a floor he was subletting on Avenue B towards the end of the 90s, things were beginning to look quite grim. But before he was forced to leave Avenue B, David received an invitation to travel to Japan, and although he was reluctant to put on a party outside his home, he ended up travelling on the basis that it could help him purchase the Avenue B space. Unfortunately, the purchase never came to pass. David returned to Japan to put on regular parties with a new friend he made during his initial trip, and he also started to put on parties with friends in London after he approached me and Colleen with the idea while “Love Saves the Day”—the book that charts his influence—was going through production.

As he went about putting on these parties, David stuck to the principles that have driven him from day one: stay faithful to your friends, find a good space for the events, get hold of the best sound equipment available, and smile when people welcome you as a guest. In the process, David drew on the life shaping experience of his orphan childhood to realize a profound philosophical lesson: homes can be built wherever you put down roots and make friends. Returning again and again to Japan and London, David realized his own universal vision, which was previously constricted to New York, but has now captured the imagination of partygoers across the globe.

Shortly after making his first trips to Japan and London, David hit upon a hall in the East Village that became the new home of the Loft, and though the parties were held on holidays rather than a weekly basis, David was convinced the dance floor that remained was as vibrant and energetic as ever. The fact David didn’t live in the space was a little inconvenient in that, with the help of friends, he had to set up his sound system each time he played, but even though he didn’t sleep in the hall, he was more comfortable in that space than any of his previous homes. “It’s in the heart of the East Village, which was where I always used to hang out,” he said. “I might have lived on Broadway, but for the other five or six days I was in the East Village. This is where I’ve been hanging out in the area since 1963. My roots are there. My life is connected to the area.” Forging new roots and connections, grandparents started to dance with their grandchildren on the floor of the New York Loft.

Thanks to David’s overdue recognition as an underpinning figure in the history of New York dance, it has become easy for partygoers to assume that the Loft has come to resemble a nostalgia trip for the halcyon days of the 70s and early 80s. Since February of 1970, however, David always mixed new and less new, even old, music, and he maintained the mix right to his final turns as a musical host. New faces in Japan and London might have arrived expecting a trip down disco alley, but that’s not what they got with David, because the party never became a fossil. Throughout, David remained committed to selecting records that encouraged the party to grow as a musically radical and diverse community. This sonic tapestry could sometimes sound strange to dancers who had become accustomed to a political climate in which communities were so casually displaced by materialistic individualism and nationalistic war, but the countercultural message was always powerful. “After a while, the positive vibe and universal attitude of the music was too much for me, but this moment of hesitation and insecurity only lasted for a few minutes,” commented a dancer following one party. “Then all the barriers broke and I reached the other side. Like a child, I stopped caring about what other people might think and reached my essence, through dancing.”

Confronted by the tendency of dancers to worship him—even though he never thought of himself as being a DJ, and was resolute in his belief that this kind of attention detracts from the party—David positioned his turntables so that partygoers would see the dance floor, and not the booth, as they entered the room. In a similar move, he also arranged his speakers so they would draw dancers away from the booth and towards the center of the floor. Admittedly in London (much more so than in New York), dancers tended to face David all the same, even though the effect was the equivalent of sitting with one’s back to musicians during a concert. At the end, dancers would applaud him as if in the presence of saviour, when he preferred to see himself as the co-host of a party whose job it was, when positioned behind the turntables, to read the mood of the dance floor. Reinforced by popular culture, which encourages crowds to seek out iconic, authoritative, supernatural leaders, the adulation made David feel deeply uncomfortable. “I’m a background person,” he noted.

Even if utopias can’t be built without a struggle, and can never be complete, the mood at the London parties was thrilling to behold during David’s visits and, in the ultimate test of his anti-ego philosophy, remained powerful after he stopped travelling on doctor’s orders. While some endowed David with a halo, a significant counter-group related to him as a friend, and the continuation of the applause in-between records and at the end of a party—when Colleen Murphy along with Simon Halpin/Guillaume Chottin picked up musical hosting responsibilities—suggested David’s argument that it was directed towards the music rather than him might be correct.

Ultimately, the party revolved around the simple idea of friends and friends of friends wanting to dance together in a comfortable and contained setting, with the music piping through clean, warm audiophile equipment, and a little talc helping participants get into the musical journey. David had indeed started the parties in London through friendship and during his time never once worked with an alternative set-up on the basis that one should stick with one’s friends. These foundations came to define the events. “It’s unbelievable,” one female dancer told me after her first party. “The people here—they make eye contact!”

David was all about contact. When he travelled to London, he was ready to accept a lower fee in order to be able to spend five nights in a hotel, not because he wanted to live it up but because he wanted to be in the city before and after each party so that he could build relationships—relationships that would feed back into the party and through the party back into the cosmos. This way of being imbued the way David related to strangers he’d meet who had nothing to do with the party. Whether we were going into a shop to buy groceries or visiting a hi-fi company to check out equipment or heading to his hotel at the end of a party, he invariably engaged with strangers as if they were all potential friends. He loved the telephone as a form of communication and for a while he was heavily drawn to the connections made possible via the Internet. Ultimately, however, he believed in the higher plane of the party.

Relationships built over a lifetime burst forth in the hours and days that followed David’s passing. Many knew David personally and spoke of him in the warmest possible terms. Others came forward as participants in a party who knew that they had entered into a nurturing environment in which social bonding and transformation were never compromised. It meant that David could live on in the knowledge that he had brought joy and hope to an incalculable number of people. “I don't want to go into the ‘I won’t always be here’ thing, but if I’m not here tomorrow, we now know what to do and what not to do,” he told me during a 2007 interview. That has come to pass as three parties in three cities in three countries in three continents are totally set to carry forward the Loft tradition in its remarkably pure form.

During dark times the Loft provided light and it will continue to do so. David understood the communal underpinnings of the party and its relationship to the universe like nobody else I ever met. Let us hang onto his words, his insights and his practice. In deepest grief, gratitude and joy, David, love is and will remain the message, music is and will remain love, love saves and will continue to save the day.

This essay is an adaptation of a 2007 article originally written for Placed. The magazine folded before the issue was published. Tim Lawrence is the author of "Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture (1970-79)," "Hold On to Your Dream: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-92," and the newly published "Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-83." He is also a founding member of Lucky Cloud Sound System, which started to put on parties with David Mancuso in London in June 2003.