This tale begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, sick with Aids and all but blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between, Walter Gibbons transformed the art of DJing and marked out the future co-ordinates of remixology.

Gibbons was born in Brooklyn on 2 April 1954. He grew up with his mother, Ann, his sister, Rosemary, and his two brothers, Robin and Edward. Nothing is known of his father -- friends say he never spoke of him -- and little more is known of his young adult life save that he subsequently moved to Queens, dated men and collected black music.

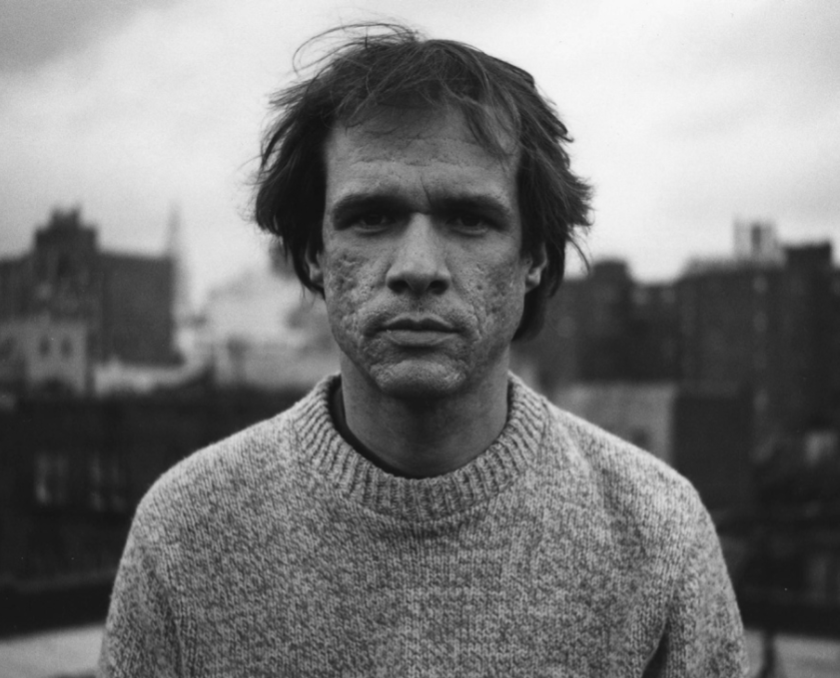

Gibbons was easy to miss. An innocuous white boy with an unconvincing moustache and carefully combed brown hair that was parted right to left, he stood at approximately five foot five and, thanks to his pencil thin build, looked like he would need help carrying his records to work. Shy and softly spoken, he kept himself to himself. He preferred cigarettes to chatter.

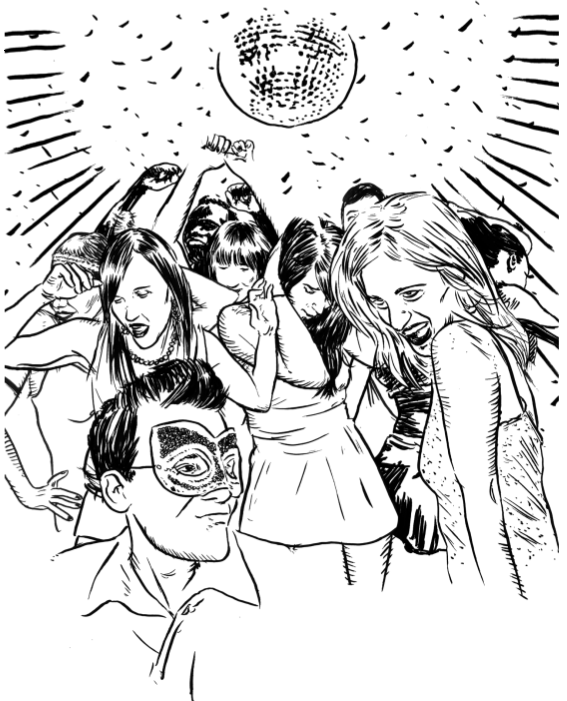

But when Gibbons stood behind the turntables at Galaxy 21, an after hours venue on Twenty-third Street owned by black entrepreneur George Freeman, he was hurricane articulate. It was almost as if he kept his daytime thoughts to himself because he knew he could articulate them with so much more force through the Galaxy sound system at night. Why talk when you can DJ?

Fiery and passionate, Gibbons was too much for Freeman, who asked soundman Alex Rosner to introduce a secret volume control so that he could lower the volume when the DJ got a little too excited. "I told George that it was a bad idea but he insisted," says Rosner. "It didn't take Walter long to figure out what was happening, so on a busy night he just walked out and most of the crowd followed him." Freeman backed down.

It was from the makeshift yet intimate habitat of his DJ booth that Gibbons established a radical new framework for spinning and, inadvertently, remixing records. Drawn to the mystical properties of musical affect, the Galaxy spinner approached his nightshift with the mindset of a nuclear physicist, aware that the process of splitting the nucleus of a song into smaller nuclei could produce a significant release of energy. And as he went about his work, he deduced that drums lay at the atomic heart of dance music.

Because there was no way for Gibbons to isolate the drum track from the rest of the multitrack, he began to hunt down songs that included a long drum intro or, alternatively, a break -- the technique transplanted from gospel and jazz into soul, funk and early disco whereby the vocalists and musicians stop playing, often instantaneously, in order to let the drummer "give it some".

Other disco DJs, most notably Nicky Siano at the Gallery, were also passionate about the potential of the break, but Gibbons acquired an unrivalled reputation for his ability to unearth these beat fragments in the most unexpected places. Rare Earth's "Happy Song", "Erucu" by Jermaine Jackson from the Mahogany soundtrack and "2 Pigs and a Hog" from the Cooley High soundtrack became trademark records. All of them were released on Motown in 1975. All of them contained an extended drum solo.

Gibbons specialized in stretching these and other percussive gems beyond the horizon of New York's tribal imaginary and, to achieve his goal, he started to purchase two copies of his favourite records in order to mix between the breaks. Tracks like "Happy Song" soon became unrecognisable. "You would never hear the actual song," says François Kevorkian, a Galaxy employee. "You just heard the drums. It seemed like he kept them going forever."

Performing in parallel yet unconnected universes, DJ Kool Herc in the Bronx and John Luongo in Boston started to play back-to-back breaks around the same time as Gibbons, but neither of them could match the Galaxy mixmaster's razor precision. And while spinners such as Richie Kaczor and David Todd were beginning to perfect the art of extended beat mixing, many of their blends were rehearsed.

Gibbons, however, combined precision and spontaneity. "Walter was making a lot of flawless mixes," says Danny Krivit, who started playing at the Ninth Circle in 1971. "He would go back and forth, very quickly, which made it sound like a live edit. It was very impressive." Kevorkian, who was hired to play drums alongside Gibbons, much to the irritation of the DJ, was also blown away by his deftness. "He had this uncanny sense of mixing that was so accurate it was unbelievable."

The fleeting identity of these drum solos also meant that it was exhausting to mix between them. "Some of these breaks only lasted for thirty seconds, if that, so these quick-fire mixes were work," says Barefoot Boy DJ Tony Smith, who became a tight friend of Gibbons during this period. "After a while Walter started to put his beat mixes on reel-to-reel at home." Everyone confirms that Gibbons was doing reel-to-reel edits before anyone else. "Walter was still doing live mixes," says Galaxy lightman Kenny Carpenter. "But if there was a mix that went over well he would perfect it on reel-to-reel."

Originally released as a one-minute-forty-second record, "Erucu" became a celebrated example of the Galaxy DJ's reel-to-reel prowess, and when Motown included an extended three-minute-twenty-four-second version of the song on the re-released album an affronted Gibbons returned to his domestic editing studio. "Walter had to do something to make his 'Erucu' be the one that everyone still wanted so he added in breaks from 'Erotic Soul' by the Larry Page Orchestra and 'One More Try' by Ashford & Simpson," says Smith, who listened to the new edit on the phone before Gibbons took it to Galaxy. "After that everyone wanted his 'Erucu' again."

Gibbons also rearranged soul records such as "Where Is The Love" by Betty Wright and "Girl You Need A Change Of Mind" by Eddie Kendricks, and in a typical set he would generate tension and drama on the dance floor with a drum edit or a live mix of drum breaks before switching to an ecstasy-inducing soul cut, often from the gospel-influenced Aretha Franklin or a Motown artist such as the Supremes. Drums, drums, drums forever followed by a vocal crescendo, this was nothing less than the house-oriented future sound of dance music.

The fact that Gibbons developed his aesthetic at a run-of-the-mill public discotheque rather than a cutting-edge private venue made his achievement all the more remarkable. "Walter was doing things other DJs wished they could try in their clubs, including me," says Smith. "The amazing thing was that Walter did what he did for a predominantly straight crowd when it was thought they weren't as musically progressive as the gay crowds."

Galaxy's after hours status, however, presented Gibbons with an opportunity that wasn't available to most midtown DJs. "You could get away with things at an after hours venue that you couldn't get away with at a regular club night," adds Smith. "After five hours people would have heard most of the things they wanted to hear and they would be ready for something new. You could go to Galaxy 21 at seven-a.m. and the club would still be packed."

Gibbons didn't acquire the cult status of David Mancuso or Nicky Siano, who were able to develop intense, almost spiritual relationships with their dancers thanks to the private status of the Loft and the Gallery, which helped create an environment that was both intimate and frenzied. That kind of rapport was impossible to establish in a public club, where crowds were transient and, more often than not, less committed to the dance ritual.

Yet Gibbons, against all odds, still became a DJ's DJ. "Everyone was going to hear Walter," says Smith, who would go down to Galaxy once he had wrapped up for the night at Barefoot Boy. "Most DJs finished at four so we could hear Walter from five until ten." After that, Gibbons and Smith would go for breakfast and, weather permitting, a trip to the beach, where they would talk about music. "DJs couldn't go and listen to too many people because we had played all night and didn't want to hear the same thing all over again. But we knew Walter would turn us on. Everyone showed up."

Everyone included Jellybean, who thought he was the "greatest DJ in the world" until he went to Galaxy. "Walter would play two records together, he did double beats, he worked the sound system and he made pressings of his own edits. I said, 'I've got to practice!'" Carpenter was also blown away. "Walter knew how to set a mood. He would take you up and bring you down. He was fierce." Smith, too, realised he was in the presence of an exceptional talent. "I heard every DJ, straight and gay, because I wanted to know what was going on in the music world. Walter was the most advanced."

All witnessed an uncompromising performer who, from the very beginning, was passionate about his music to the point of zealousness.

* * * * *

Walter Gibbons didn't just electrify fellow DJs and suburban dancers. He also electrified Ken Cayre, head of a newly formed label called Salsoul, which had created a minor tremor in Nightworld with the release of the Salsoul Orchestra's debut album. The Salsoul boss proceeded to sign Double Exposure and realised soon after that Gibbons could help him market the group's first single. "Walter was very aggressive when it came to searching out new records," says Cayre. "He became friendly with Denise Chatman, our promotions girl, and we went to hear him play. I was very impressed with his skills."

Cayre was particularly taken with the way the DJ worked "Ten Percent", which had been released as a non-commercial promotional twelve-inch test pressing that consisted of the standard single plus a longer version. "We knew the DJs wanted longer records so we told the producers to get the musicians to jam for a couple of minutes after they had recorded the regular song," says Cayre. "I had to release the promotional twelve-inch single because the seven-inch wasn't doing well." Having laid his hands on two copies of the test pressing, Gibbons worked up a whirlwind. "He did this fantastic edit and the reaction in the club was phenomenal. I said, 'Can you do that in the studio?' He said he could."

Salsoul gave Gibbons and engineer Bob Blank three hours to complete the remix at Blank Tapes Studios. That meant the duo had one hour to put up the mix and channel the sound, one hour to break down the recording and one hour to cut up tape with a razor blade. "Walter was prepared but he couldn't prepare everything," says Blank. "He had to be ready to do 'brain work' on the spur of the moment. The session was very intuitive. Walter was a real genius."

By the end of the session the diminutive DJ had transformed a dense four-minute song into a nine-minute-forty-five-second roller coaster. He was paid $185 for his efforts -- $85 to cover a night's work at Galaxy, plus $100 for the blend -- and he started to spin an acetate of the remix, which was effectively a readymade version of the lightning-quick collages he had already been concocting at Galaxy, in late February/early March 1976.

"'Ten Percent' was one of the best mixes anyone had ever heard," remembers Smith. "Walter turned a nice song into a peak song." The remix became an instant classic. "I heard it on an acetate in the Gallery," says Mixmaster editor and downtown connoisseur Michael Gomes. "It sounded so new, going backwards and forwards. It built and built like it would never stop. The dance floor just exploded."

Salsoul released the twelve-inch -- the first commercially released twelve-inch -- in May, much to the chagrin of the Philadelphia-based songwriter Allan Felder. "The mixer cut up the lyrics and changed the music," Felder told me shortly before he passed away. "It was as if the writers and producers were nothing."

Gibbons didn't set out to offend. Blank notes the DJ-turned-remixer was "very, very, very concerned" the artists, producers and writers would feel he had done the record justice. But DJs were widely regarded as musical parasites and the idea that they should be given carte blanche to remix an original work of art was doggedly opposed by music-makers. The development was seen as being nothing short of scandalous and Gibbons lay at the centre of the action.

Cayre stayed calm and kept his focus. "Walter was the first DJ to show the record companies that they should be open to different versions of a song," he says. "They were in the club night after night so they knew what worked and what didn't work. Walter was pivotal. He convinced producers and other record companies to give the DJs an opportunity to remix records for the clubs. And he showed us that these records could be commercially successful. People didn't believe that was possible before 'Ten Percent'. Walter was a pioneer."

Gibbons remixed "Sun… Sun… Sun…" by Jakki around the same time as "Ten Percent" -- maybe just before, maybe just after. Produced by Johnny Melfi and released on Pyramid as a twelve-inch in 1976, the record contains no reference to Gibbons, but Chatman, who was nicknamed "Sunshine" because of her ultra-cheerful personality, remembers Gibbons phoning her up to tell her he was remixing the record. "Walter called me and said, 'Sunshine, sunshine, sunshine!'" she remembers. "Then he told me the name of the record."

"Sun… Sun… Sun…" hit the Record World disco charts in July, a good two months after "Ten Percent", which suggests the record was remixed after "Ten Percent". Then again, the omission of Gibbons' name suggests "Sun…" was released first: the "Ten Percent" twelve-inch was such an overnight sensation that no label head in his right mind would have dreamed of omitting the remixer's name from the label. The roughness of the mix adds further weight to the theory that it was put together before the much smoother "Ten Percent".

As for the record, "Sun…" is divided into three parts: the regular song (which was released as a single), followed by a looped break (which was snatched from the beginning of the second side of the original seven-inch), followed by a mix of the A and B-sides of the seven-inch. The break -- highly percussive, with trippy vocal bites fading in and out -- was typical of the drums-for-days reel-to-reels Gibbons was compiling for his dancers, and it was this section of the record that his contemporaries loved.

"It was a really bad song and Walter turned it into a nine-minute mix," says Smith, who received an acetate of the remix and remembers that it was slow to attract attention thanks to the fact that Pyramid was a small company and the song was so off-the-wall. "The twelve-inch was very long and included this three-minute break. We would just play the break and after a while we grew to like the rest of the song. The record got no play until it was mixed by Walter."

Whatever the relationship between Gibbons and Pyramid, however, it was Cayre who formed a landmark affiliation with the remixer, and the Salsoul boss further demonstrated his faith in the Galaxy DJ when he agreed to let him remix "Nice 'N' Naasty" and "Salsoul 2001" by the Salsoul Orchestra -- which was headed by the notoriously touchy Vince Montana, of Philadelphia International fame.

The remix of "Nice" included a trademark thirty-second percussive break, yet it was the B-side that came close to giving Nightworld a collective seizure. "Salsoul 3001" -- a the remix of "Salsoul 2001" was renamed -- opened with jet engines, animal whoops, congas and timbales before soaring into a powerful combination of orchestral refrains and synthesised sound effects that were played out against a backdrop of relentless Latin rhythms.

"This has got to be one of the year's most extraordinary products and although it may be too overwhelming and bizarre for some clubs, others, like New York's Loft, turn to pandemonium when the record comes on," reported Vince Aletti in his highly regarded "Disco File" column in Record World. "Experiment with it if you haven't already." If Tom Moulton had set out the fundamentals of remix culture with reworkings of "Dream World", "Do It ('Til You're Satisfied)", "Never Can Say Goodbye", "Make Me Believe in You" and "Free Man", "Salsoul 3001" confirmed that Gibbons was taking the new artform to a freakier level.

"Walter did this weird, off-the-wall stuff with '3001'," says Moulton, who also entered Salsoul's remix fold in 1976. "I said, 'Walter, what was going through that brain of yours for '3001'?' It was nothing like '2001'." Moulton concedes that he "couldn't understand" the aberrant angles of the revamp. "It was like Walter wanted to come out with an album that was tripping. But I didn't like Vince anyways so I thought, 'Serves him right!' Walter was the first radical one."

That militancy was given its fullest expression on the DJ's remix of Loleatta Holloway's "Hit And Run", which was recorded at Sigma Sound in April 1976 and released on Holloway's album, Loleatta, in December. Gibbons asked Cayre if he could remix the song and the Salsoul chief, taking a deep breath, decided to entrust his little prince with the multitrack. "'Hit And Run' was the first time that a studio let a DJ completely rework the song," says Cayre, "and Walter, the genius that he was, turned it into a twelve-minute, unconventional smash."

Having been restricted to carrying out a cut-and-paste reedit of the half-inch master copies for "Ten Percent", Gibbons was now able to select between each individual track, and he dissected and reconstructed the six-minute album version in the most sweeping manner imaginable: a swathe of strings and almost all the horns were sliced out in order to emphasise Baker, Harris and Young's exquisite rhythm track, and, in a high-risk move, the remixer shifted the focus of the song by cutting the first two minutes and all of the verses of Holloway's vocal.

Gibbons' motives were clear. Any song that began "Now I might be an old-fashioned country girl, but when it comes to loving you, honey, I know what to do" was never going to inspire the urban dance floor. Yet the second, improvised half of Holloway's performance, which consisted of an extended series of lung-busting repetitions, screams, tremors and sighs, was quite extraordinary and, having filled up three minutes on the album, Holloway's vamps were now run for a long five minutes on the twelve-inch.

"She was always wailing or moaning or singing and we just reintroduced the stuff that had been cut or buried," says Chatman, who hung out with Gibbons in the studio during the remix. "Walter just took the multitrack and said, 'Ooh, did you hear her do that!' He was like a child in a candy store. There were so many choices. He wanted all of them and it just became long." Eleven minutes seven seconds long.

Salsoul's bigwigs were aghast. "When Walter played me his mix I initially wanted to choke him," says Cayre. "Loleatta wasn't there anymore. Walter just told me that I had to get used to it." Always up for a party, the mogul went to listen to Gibbons play the twelve-inch in its intended setting and "after hearing it a couple of times" he knew that Gibbons "had done the right thing."

Producer Norman Harris was even more concerned than Cayre. When he sent a coy of the recording to Moulton, he included a note on the reel that asked, "Does this have any musical merit?" "I told Norman, 'You're looking at it as a song whereas Walter is trying to get the most out of it for the dance floor,'" says Moulton. "If it was down to Norman the remix would have never seen the light of day."

Moulton reviewed the record in his "Disco Action" column in Billboard at the beginning of May 1977. "Many of the breaks on this record are unpredictable, and convey the impression that the mixing deejay was working with a full floor of dancers and was going out of his way to 'do a number' on the audience," he wrote. "This version is really so different from the original that it must be classified as a new record."

Backed with "We're Getting Stronger", "Hit And Run" caused a sensation in the clubs. "I remember every DJ just loving it," says Smith. "I heard it everywhere I went and the crowds just went crazy." The newness of it all was hard to quantify. "Everyone was used to the uniform Tom Moulton mix of the intro, the vocal, a little instrumental part and then a fade-out on the vocal," adds Smith. "But Walter changed the whole sequence of the song. He did it a bit with 'Ten Percent' and he did it even more with 'Hit And Run'. To think that he was just this kid."

The twelve-inch of "Hit And Run" went on to sell some three hundred thousand copies -- more than both the "Ten Percent" twelve-inch and the "Hit And Run" seven-inch -- and by all accounts the sales went a long way towards placating Harris. It was a significant development. A DJ had revised a leading producer's work beyond recognition, the remix had outsold the single, and the producer was happy. The balance of power was shifting within the music industry, and Gibbons lay at the centre of the transition.

* * * * *

"Ten Percent" and "Hit And Run" established Salsoul as the favourite label of New York's insomniac DJs, and for the first half of 1977 Walter Gibbons continued to be its most prolific remixer. True Example's beautifully tender "Love Is Finally Coming My Way" (backed with "As Long As You Love Me") contains a classic Gibbons break and was considered by many to be one of his strongest mixes to date, while Love Committee's "Cheaters Never Win"/"Where Will It End", a sweet-sounding falsetto recording, was restructured in a similar vein.

During this period, Gibbons also remixed Anthony White's "I Can't Turn You Loose", a rather mundane cover of an Otis Redding classic that contained a radical instrumental edit on the B-side, which was renamed "Block Party" -- and intriguingly credited to Baker, Harris and Young. Barely pausing for breath, Gibbons also remixed "Magic Bird Of Fire", upon which he stretched out the Salsoul Orchestra's slightly demented strings around various layers of shifting percussion. In all likelihood these mixes were completed before Gibbons segued and looped a selection of Salsoul releases, Disco Boogie: Super Hits For Non-Stop Dancing, in the summer.

The DJ, however, had no time to get carried away with his studio success, having quit Galaxy 21 towards the end of 1976 when he discovered that his sets were being secretly recorded. If that had been the end of the story, Gibbons might have stayed, but it also became clear that tapes of his prized reel-to-reel edits (which he would only hand out to his closest friends, and then only reluctantly) were being taken to Sunshine Sound. From there they were being reproduced and sold on the black market. It was as if his genetic code had been ripped out of him for a fistful of dollars. Gibbons had left Galaxy before, but this time there could be no going back.

Galaxy 21 closed around the beginning of 1977 -- the after hours venue was never going to survive without its star spinner -- and Gibbons spent the next six months bouncing from undistinguished club to undistinguished club, notching up Crisco Disco, Fantasia and Pep McGuires along the way. "The business had changed and it wasn't Walter's era anymore," says Kenny Carpenter. "He couldn't play at places like 12 West because he didn't play raving faggot music. Walter was too soulful for that."

To a certain extent Gibbons had already tasted the experience of being a DJ vagabond, having failed to hold down alternate spots at Limelight, Better Days and Barefoot Boy, three of the most popular clubs of the early to mid-seventies. In each instance his tenure proved to be short-lived because he wasn't prepared to compromise his style and adapt to the demands of a new crowd.

"Walter was too experimental and too creative," says Tony Smith, who handed Gibbons the Monday and Tuesday-night spots at Barefoot Boy. "Most DJs trained their crowd to know them, but Walter was known for being Walter and he didn't want to change." Smith tried to tell his friend that he had to modify his style for Barefoot Boy, which wasn't an after hours club, but he got nowhere. "Walter was not good at compromising. He was steadfast in what he wanted to do. He could be so stubborn."

When Galaxy closed, Gibbons was left in the lurch. The Loft, the Gallery and the newly opened Garage were impregnable thanks to the hallowed presence of David Mancuso, Nicky Siano and Larry Levan. The white gay private party scene, which was dominated by Flamingo and 12 West, wanted a sweeter sound than Gibbons was willing to deliver. And the major public discotheques, which included Studio 54, Xenon and New York, New York, were on the lookout for jocks who were willing to keep the dance floor moving to a smooth and steady pop-oriented tempo.

In search of a new DJing home, Gibbons travelled to Seattle and worked in a new George Freeman discotheque, the Monastery, in mid-1977. "He worked with George in Seattle because he couldn't get anything in New York City," says Smith. However his relocation to the upper reaches of the West Coast evidently didn't work out because the discontented DJ returned to the East Coast some time during the first half of 1978. Then, in July, he re-entered the Salsoul fold to deliver a remix of Love Committee's "Law And Order" and "Just As Long As I Got You".

For "Law And Order" Gibbons dissected the cluttered-up original, grabbing a series of instrumental phrases and vocal hooks, which were weaved around an elevated, insistent bongo-driven percussion track. Stripped down and driving, the result was nothing less than a blueprint for the decentralised future of electronic dance.

Yet the remix of "Just As Long" caused even more of a stir thanks to the three minutes of discordant drama added to the end of Tom Moulton's original remix. "I said, 'Walter, what you've done with the keyboards is spectacular,'" remembers Moulton. "The keyboard was there, but I didn't pick up on it. I said, 'Walter, you did a fantastic job on that!'" Moulton openly acknowledges that Gibbons took his remix to the next level. "I complimented him and he was taken aback."

The "Just As Long" release was an event -- the first time that a remixer had remixed a remixer -- and inevitably attracted comparisons between Moulton, who was confident, gruff and impossibly handsome, and Gibbons, who was withdrawn, soft and quirkily odd-looking. Yet it was their studio work that counted, and in this respect Moulton was conservative and melodic, while Gibbons was avant-garde and discordant.

"Walter always said he liked what I did but thought I was very tame," says Moulton. "I told him, 'My aim is to eliminate everything that is a turnoff so that I will have a hit record.'" It was this mindset that persuaded Moulton to develop a standard seven-inch mix with a short intro whenever he went into the studio. "I wanted to get radio play. I said, 'Walter, I'm coming from a totally different place -- retail, wholesale, promotion.'"

Gibbons had an alternative objective: to remix records for the underground. "He didn't think in commercial terms," adds Moulton. "He thought of himself as a jazz musician who didn't want to sacrifice his craft to the system. I always thought that attitude was bullshit." Gibbons didn't shy away from the confrontation. "He told me, 'Tom, you're not drastic enough. You stay too close to what's there.'"

The two remixers were finally driven by contrasting aesthetic preferences. "I wanted stuff to sound real, like a live performance," says Moulton. "The more live it was, the more your body could react." Gibbons came from another place. "He was into drugs and developed weird sounds. It was like he wanted to make music you could trip to. I couldn't understand his sounds and I still can't because they don't make sense to me musically. I wasn't on his level, whatever that level was."

That level, however, wasn't organised around drugs: Smith notes that he and Gibbons would occasionally take blotter acid and smoke pot when they DJed or went to hear other DJs ("usually Larry Levan") but insists the drugs were always secondary to the music. "It was all about enhancing and expanding our creative juices," says the Barefoot Boy spinner. "We wouldn't do anything that was overpowering because that would stop us focusing on the music. The drug wasn't the high. The music was the high. Walter and I would get a rush many times without drugs."

Indebted as they were to Moulton for pioneering the disco mix, New York's DJs regarded Gibbons as their reigning remix deity. "Tom was first and he was consistent all the way through, but Walter's mixes were outrageous and quickly got a lot of attention," says Danny Krivit. "Tom was by no means out of the picture, but Walter was much more irreverent and very much the remixer of the moment."

That irreverence found its fullest madcap expression on two relatively obscure Gibbons releases -- "Moon Maiden" by the Duke Ellington-inspired Luv You Madly Orchestra (the B-side of the more conventional "Rocket Rock") and Cellophane's "Super Queen"/"Dance With Me (Let's Believe)" -- which were evidently part of Salsoul's ill-judged decision to release as many disco acts as possible in 1978 in the belief that everything the label touched would be transformed into disco gold.

The vocals on these tracks are middle European Abba on a cocktail of amphetamines, acid and helium. Instead of smoothing out the strangeness, however, Gibbons accentuated the effect, intertwining the contorted voices with a series of modulating synthesisers and stabbing strings, all laid over an insistent and shifting bongo-driven beat track. Neither record received much attention, but Gibbons was probably having too much fun to worry about that.

During the same period Gibbons mixed Loleatta Holloway's "Catch Me On The Rebound" (for Salsoul), Sandy Mercer's "Play With Me" backed with "You Are My Love" (for H&L), and Bettye LaVette's "Doin' The Best That I Can" (for West End). The Holloway, a professional mix of strong if uninspired song, was notable for its extended break, during which Holloway vamped over thumping drums and bouncing bongos. The Mercer, for which the late Steve D'Acquisto received a co-mixing credit, was noteworthy for the B-side mix, which was a favourite of Ron Hardy in Chicago and Larry Levan in New York.

Yet it was the LaVette remix that shone through this little cluster of releases. "Doin' The Best" amounted to a stirring eleven-minute epic remix that encapsulated Gibbons' aesthetic of trance-like-build-to-emotional-release, segueing from an instrumental build to the vocals before setting off on a disorienting rollercoaster ride of bongos, handclaps, tambourines and shimmering instrumental interludes. As the music critic David Toop later remarked, the remix "opened New York dance to the potential of dub deconstruction."

Gibbons also received an unprecedented level of album work during 1978: he blended the first volume of Salsoul Orchestra's Greatest Disco Hits and the second volume of Disco Boogie, and he was also co-credited, along with Tom Moulton and Jim Burgess, with compiling Salsoul's Saturday Night Disco Party. For all of his problems holding down a spot in Clubland, the ex-Galaxy DJ, was on top of the remix mountain. Everything was going swimmingly.

* * * * *

Then something mysterious happened.

Either Walter Gibbons was handed the task of remixing Instant Funk's "I Got My Mind Made Up", came close to completing the mix, but then became a born-again Christian and said he would only finish the job if Ken Cayre recorded some new vocals, at which point the Salsoul boss asked Larry Levan to finish off the remix -- for which the Garage DJ was wholly credited.

Or Gibbons was never handed the Instant Funk remix, which was given straight to Levan, who went into the studio on 4 December 1978 and did what he had to do. Having completed just one other mix -- "C Is For Cookie" by Cookie Monster & The Girls, which came and went without causing much of a stir -- Levan came out with one of the most mesmerising, earth-shattering remixes of all-time.

Ever since the release of "I Got My Mind Made Up", the first version of the story has been nothing more than a flickering rumour familiar to a handful of New Yorkers -- plus Colin Gate, a Glasgow-based dance producer and record collector who, having travelled to Manhattan in the mid-nineties to work for Will Socolov and Todd Terry, was given the opportunity to purchase Gibbons' record collection following the DJ-remixer's death in 1994. When Gate told me about the story, I asked the key parties what had happened.

"I worked for weeks on the record," remembers Bob Blank. "Walter started on the mix but then refused to carry on because he became very religious. I remember him saying very specifically, 'I really don't think I'm going to be working on this record anymore.'" Blank and Cayre subsequently worked on the remix for almost a week in Studio A. "We worked on it after Walter left the project. I brought in a lot of stuff and I have to credit that to Walter. He was the ultimate arbiter."

Blank says that he and Cayre never intended to finish the remix, and that Levan came in at the very end. "Larry was brought in after we had worked on this record forever. Larry basically had very little input on 'I Got My Mind Made Up'. All the groundwork had been done and he only came in for a few hours. But it was Larry who made the nine-minute version. It was never nine minutes before he came in."

Cayre has a different memory of the remix. "Walter never went into the studio with 'I Got My Mind Made Up'," he says. "Larry was playing the record at the Paradise Garage and loved it. We went to see the edits he was doing and we asked him if he wanted to do a remix. We asked Larry because he was getting the best reaction of all the DJs." Cayre says the Garage mixer was a sensation in the studio. "Larry really took the record to a different level. He was very comfortable and really tore into the song."

However Denise Chatman, who was tight with both Gibbons and Cayre, remembers Gibbons being involved, too involved, with the Instant Funk track. "Walter's whole being was taken over by something else during the remix of 'I Got My Mind Made Up' and that made Kenny very, very nervous," she says. "Walter became very judgemental of everybody around him -- he was against any kind of cursing -- and he became very uncomfortable with the material."

Having stretched the boundaries of remix culture to breaking point, Gibbons went a step too far. "Walter asked Kenny to change the lyrics and there was no way that was going to happen," says Chatman. "I told Walter he was being totally unrealistic. Kenny then went with Larry." Chatman adds a cautionary note. "Did I witness these conversations? No. But I was in touch with Walter for quite a while and I remember as clear as can be that the lyrics to Instant Funk made him very uncomfortable."

Chatman insists that Cayre was acting with the best intentions. "Kenny was more than willing to let Walter finish the mix. Kenny is a stand-up guy. If he believes in you he will stand by you through everything." According to Chatman, Cayre was absolutely crazy about Gibbons and Gibbons thought the world of Cayre. "There is no way in the world Kenny would have ever taken the mix away from Walter. They had a real bond. Walter just became uncomfortable with the material. What can you do in a situation like that? The music is what it is."

The events of the "I Got My Mind Made Up" remix happened some twenty-five years ago. Since then, memories have faded and seeped into each other to the point where absolute clarity over what happened when and why has been lost, or at least put on hold. History isn't always a blur, but it can be, and, for the time being at least, the truth behind Instant Funk must remain suspended, especially as Gibbons and Levan are no longer around to provide their version of the story.

Yet the elusive truth behind "I Got My Mind Made Up" matters because the twelve-inch is widely considered to be one of the most spellbinding remixes -- if not the most spellbinding remix -- of the 1970s. It helped propel the single to the top of the R&B charts and it launched Levan onto the remixing map. With the dubious benefit of partial hindsight, it could now cement Gibbons' reputation as the most influential remixer of the 1970s.

The Instant Funk twelve certainly sounds like a Gibbons Galaxy reel transposed onto vinyl. A deceptive sweet-lush intro is followed by a crackling percussive break interspersed with a rhythm guitar, repeated snippets of the song's upfront chorus and an extended keyboard jam, followed by the incredulous female reply of saaay whaaat? Then, in its full-frontal glory, comes the chant of I got my mind made up, come on, you can get it, get it girl, anytime, tonight is fine. The instrumental track and vocals ensue, producing a room-rocking crescendo, before the track cuts to another deep-down break, during which the bass and rhythm guitars groove over an undulating percussive backdrop. A final reprise of the song concludes the track.

The swirling structure and drum-happy attitude is classic Gibbons -- everlasting beats followed by a vocal release to the power of two -- so if Levan did mix "I Got My Mind Made Up" it should at least be acknowledged that he was adopting Gibbons' template beat for beat, phrase for phrase. Levan may have developed his own unique style during the eighties, but this much cannot be said of the ghetto-style groove of Instant Funk.

"'I Got My Mind Made Up' is very much in the style of Walter, so I wouldn't be surprised if he mixed it," says Danny Krivit. "But that doesn't mean that Larry didn't feel the record in the same way." Krivit notes that Levan's remix of "C Is For Cookie" is "much gutsier" than Roy Thode's flipside, so it's conceivable the Garage DJ could have come up with the Instant Funk remix. But whatever the truth, Levan's legacy will remain unaffected. "Larry wasn't credited with doing that many great mixes in the seventies. He did a few, but the eighties was really his decade."

Gate, now back in Glasgow, senses that Gibbons might be viewed differently if he had been credited with the "I Got My Mind Made Up" remix. "Instant Funk took Larry from being just another New York DJ to being a contender in the record industry overnight," he says. "There is no doubt that Larry would have made a name for himself as a remixer without it. But if Walter and not Larry had been credited with Instant Funk, Walter might have been known as the genius."

* * * * *

The relationship between Walter Gibbons and Salsoul may have been drawing to a close, but it wasn't over. In March 1979 Cayre released Disco Madness, which included six new Gibbons remixes and was issued as both a regular album and a DJ-friendly double-pack. "It was the first time a label released an album of mixes by a single remixer," says Ken Cayre. "Every DJ was inspired by Walter."

All of the mixes were radically different to existing versions -- some of which had already been mixed by Gibbons-- and marked a hardening and deepening of his aesthetic. "I don't consider Disco Madness to be a mix of the original music," says Tom Moulton, who regarded the new versions to be so far-reaching that they amounted to new songs. "It wasn't called Disco Madness for nothing. Most people felt the same way. I always said, 'If you want to know anything about that album, ask Walter.'"

On the first part of the double-pack, Gibbons revisited "Magic Bird Of Fire" and, remixing his own remix, elevated the beats and lowered the instrumentation. Faced with the challenge of reworking "Ten Percent", the studio whiz zoomed in on bongos and deep down keyboards. When it came to "Let No Man Put Asunder", a buried album cut by First Choice, he generated a dub-like workout of stripped down beats, sunken synthesisers and subtly echoed vocals.

For part two, Gibbons laid down a fierce, skipping beat for "It's Good For The Soul" and interspersed the chorus with his own infectious chants of "alright", "woo-ooo", "it's good for the soul" and "alright-alright-alright-alright-alright-alright-alright-alright" -- as if, unable to contain himself in the control booth, he kept on skipping into the studio to have a quick dance. The penultimate remix, "My Love Is Free", originally a Moulton twelve-inch, became so deep it almost disappeared into itself. To round things off, "Catch Me On The Rebound" was whittled down to the beats and Holloway's vamp.

Gibbons mixed two more twelve-inches for Salsoul in 1979: two Double Exposure album cuts, "Ice Cold Love" and "I Wish That I Could Make Love To You", plus "Stand By Your Man"/"Your Cheatin' Heart" by the Robin Hooker Band. All displayed a southern-soul-veering-into-gospel vibe that would have appealed more to a church barn dance than a drugged-up dance floor. Catchy, hypnotic and stomping, yet occasionally cheesy, they sounded like the work of a man who had an extraordinary feel for dance music but had fallen out of synch with Clubland.

That was reflected at Salsoul HQ, where the big remixes were going to other DJs. Tee Scott remixed "Love Thang" by First Choice and "Slap, Slap, Lickedy Lap" by Instant Funk. Bobby "DJ" Guttadaro went into the studio with Bunny Sigler's "By The Way You Dance", First Choice's "Double Cross" and Loleatta Holloway's "Greatest Performance Of My Life". And Larry Levan remixed just about everything else: Instant Funk's "Body Shine", plus six tracks for his Salsoul remix album --"Double Cross", "First Time Around", "Greatest Performance Of My Life", "Handsome Man", "How High" and… "I Got My Mind Made Up".

Levan also started to receive big remix commissions from other labels in the same year, including "Give Your Body Up To The Music" by Billy Nichols (West End), "When You Touch Me" by Taana Gardner (West End) and "Bad For Me" by Dee Dee Bridgewater (Elektra). All of these records were huge on the dance floor and, combined with his Salsoul work, make it clear that, even without the Instant Funk, Levan would have still established himself as a remarkably talented remixer by the end of 1979.

Gibbons, meanwhile, started to feed on scraps. His remix of Colleen Heather's "One Night Love Affair" for West End skipped along in a fairly predictable manner before breaking into a series of wild beats and handclaps interspersed with bass, horns and vocals. Released in the same period, his version of Gladys Knight & the Pips for Buddah also veered between the conservative and the crazy: "It's Better Than A Good Time" was a comparatively conventional, gospel-oriented effort, while the incredibly groovy flipside, "Saved By The Grace Of Your Love", featured southern-style yee-haas, handclaps and hallelujahs, all recorded at a sky high beat-per-minute tempo that would have flummoxed the most dextrous dancer (and probably wasn't intended for them in the first place).

Gibbons continued to DJ during this period, holding down spots at the Buttermilk Bottom and Xenon, but his sets became increasingly bizarre and his residencies increasingly ephemeral. "I got Walter his job at Xenon and the owners complained because he only played gospel and Salsoul," says Tony Smith, who had been working at the midtown location seven nights a week and was on the lookout for a helping hand. "I said, 'Walter, you can't do that!' There was so much great music out there at the time. Larry was coming out with all this new stuff. But Walter wouldn't change and after three weeks they told me to fire him."

Smith was shocked at the metamorphosis. "When I met Walter he was so wide-ranging. You didn't know what he was going to turn you onto. He could make a rock record sound like disco." Now, however, Gibbons was using a marker pen to blot out any unsavoury words that appeared on his records, as well as highlight any song titles that contained the word love with a heart. "His musical horizon shrank. All of a sudden the music had to have all these big messages and he wouldn't play any negative songs." Smith had no choice but to sack his friend. "It wasn't good. We fell out over that."

Somewhat inevitably, Gibbons also fell out of synch with the studio circuit. "Ken Cayre always went for the hot thing," says Bob Blank. "Larry became hot and Walter didn't have a base." The competition was growing and Gibbons was becoming yesterday's man. "It's the pop business," adds Blank. "Nobody's a star forever." Gibbons continued to hang around Blank Tapes Studios, but had become a peripheral figure. "Mel Cheren would call him when Kenny Nix was recording Taana Gardner and Walter would show up. He was always very cordial. I think he just didn't have the drive to become a star."

Gibbons was travelling backwards in time. Twentieth century popular culture in the United States had been defined by the tension between Saturday night partying and Sunday morning prayer, with the spirituality of gospel gradually giving way to the corporeality of the blues. Gibbons, however, was moving in the opposite direction, swapping the sin of sex for the salvation of God, and nobody else from the New York underground was willing to join him on his journey. "When Walter went religious he alienated all of his friends," says Kenny Carpenter. "He was really fanatical about the whole thing."

That didn't stop Steven Harvey from profiling Gibbons -- now sporting a mullet-shaped perm -- in his seminal overview of the New York underground, "Behind The Groove", which was published in Collusion in September 1983. Having met at Barry's, a record store on Twenty-third Street where Gibbons recommended danceable gospel tracks such as "Things 'Have' Got To Get Better" by Genobia Jeter, they reconvened at Harvey's apartment. Gibbons arrived with some homemade acetates of Philly-style tracks that included his own vocals. "They definitely had the spirit," Harvey later recorded.

Gibbons told Harvey that he was now playing records at his own house parties and added that he took requests, even for records that he considered to be unchristian, because that could help him get into the mindset of his dancers and help reshape their outlook. When one dancer asked him to play "Nasty Girls", Gibbons put it on, and then segued into "Try God" by the New York Community Choir. "For me, I have to let God play the records," he told the writer. "I'm just an instrument."

The last time he saw Scott, Gibbons added, he gave the Better Days DJ a mix that blended "Law Of The Land" by Undisputed Truth, "Ten Percent" by Double Exposure and a spoken version of the Ten Commandments. "He played it and the crowd roared like I've never heard in my life," Gibbons told Harvey. "Especially after the part where he's saying 'thou shalt not commit adultery, though shall not steal, though shall not kill' -- there was such a roar." Gibbons said he was taken aback. "It was very interesting." The DJ's proselytizing outlook had become more entrenched than ever.

* * * * *

Popular opinion had it that Walter Gibbons had traveled to Cloud Cuckoo Land and wasn't about to come back anytime soon, but in 1984 he approached his old friend Tony Smith, who was now the alternate DJ at the Funhouse, and handed him two white test pressings of a new recording. "I knew I had to play it otherwise we would never be friends," remembers Smith.

The record in question -- "Set It Off" by Strafe, the debut release on Jus Born Records, which was co-owned by Gibbons -- was a revelation. The vocals, performed by Steve "Strafe" Standart, a childhood friend of Kenny Carpenter, were mesmerizing, and the sparse rhythm track, all syncopation and repetition, brought together the seemingly incompatible worlds of breakbeat hip-hop and the downtown underground onto a single slab of vinyl. Once again Gibbons had taken a gravity-defying leap into the future of dance.

The Funhouse crowd, however, wasn't ready for Strafe. "They were really into the Arthur Baker sound," says Smith. "I played 'Set It Off' for ten minutes and it cleared the floor. Everyone in the booth was stunned by the record -- it was so incredible and different -- but Walter left under a real cloud. He was really disgusted. I said, 'Walter, there's no one here over eighteen!'"

When Smith discovered that lightman Ricky Cardona had made a reel-to-reel tape of his set, he made a copy of "Set It Off" and started to play the record once a night until, after a month of extremely careful programming, his dancers started to ask him the name of the unreleased track. "They didn't know the name of the song so they were calling it 'On The Left'," says Smith.

By the time Gibbons returned to the club to give the alternate DJ a copy of the vinyl, "Set It Off" had become a dance floor favorite. "Everyone screamed when I put it on," says Smith. "Walter was totally shocked. He eventually gave me all these other mixes of the song, including a reggae version." "Set It Off" became a Funhouse classic. "The original song was four minutes long and really sucked. I couldn't believe Walter got eighteen minutes out of it. The artist really hated Walter's mix. He didn't have Walter mix his next song and we haven't heard of him since."

Even though he was spending more and more time in the studio and would eventually leave the Funhouse in the summer, Jellybean also played "Set It Off". "It was very, very different to everything that was out there," says the DJ. "It had soul, it had electro, it had Latin. It had a whistle in it, and a lot of the kids on the dance floor would bring whistles. It was a long record that took you on a journey. It captured so many different things -- and it had just the right energy."

In June 1984 Billboard described "Set It Off" (which carried the inscription "Mixed with Love by Walter Gibbons") as a "low-budget production making some substantial neighbourhood noise here in New York, in the same way unusual cuts by Peech Boys and Loose Joints have." Yet while Larry Levan broke Peech Boys and Loose Joints at the Garage, "Set It Off", which was a little too electro-oriented for the King Street crowd, followed a different trajectory.

"Strafe got played at the Garage quite a bit, but it was getting more play in a lot of other places," says Danny Krivit. "It was unbelievably big." By this point Krivit spinning in a number of venues, including the Roxy, Down Under, Laces, Area and occasionally Danceteria, and "Set It Off" worked in all of them. "I could play the record all night, wherever I was DJing. I could play it on the worst sound system and it still sounded good. It was just this huge thing for me."

For his second release on Jus Born, Gibbons returned to the more familiar build-and-break template of his 1970s remixes, although it's hard to think of a more beautifully executed version of this aesthetic than "Searchin" by Arts and Crafts. Having laid down a hypnotic bongo beat, Gibbons brought in a dreamy bass, soulful male and female vocals, a gentle keyboard and a jazzy sax, and he gave each new part its own discrete space in which to evolve. The result was an almost wistful yet ultimately uplifting tapestry of decentralised, floating sounds in conversation with each other -- the future sound of deep house incarnate.

There was, however, no record industry rush to sign up Gibbons and, left with no choice but to plough his own groove, the idiosyncratic evangelist teamed up with Barbara Tucker, then an unknown gospel vocalist, to produce a remix of "Set It Off". Released in 1985 under the moniker Harlequin Four's, the record was the third (and probably last) issue on Jus Born Records. "After 'Set It Off' I thought he would get back into the music business," says Smith. "The record went to number one. But nobody gave him any offers."

Gibbons recorded two of his final releases with the avant-garde cellist Arthur Russell, who had started to produce dance records following his introduction to the Gallery in 1977. Having co-produced "Kiss Me Again" with Nicky Siano in 1978, Russell asked to be introduced to Gibbons after he heard Sandy Mercer's "Play With Me", and Steve D'Acquisto, who went on to record "Is It All Over My Face" with Russell, arranged for the two of them to get together.

Gibbons remixed an unreleased version of Russell's seminal "Go Bang" -- "Walter's mix is very different to the François mix," says Colin Gate. "It's weirder with loads of crazy things happening" -- and the two sound sculptors reconvened when Russell, who loved "Set It Off", asked Gibbons to mix "Schoolbell/Treehouse", which would later re-emerge as a voice-cello solo on Russell's meditative dub album, World Of Echo.

Released on Sleeping Bag in 1986, the Gibbons mix of "Schoolbell/Treehouse" revolved around a spaced-out array of bongos, piercing hi-hats, discordant synth stabs, scratchy cello solos and hovering trombone passages, maintaining a steady-but-jolty tempo before accelerating to a heart-attack finale. Wispy yet self-assured, Russell's voice presided over the mayhem, guiding the listener into the deep-down world of demented dance. "Walter could discuss the different textures of music for days," says Sleeping Bag owner Will Socolov. "The only other person who discussed sound in that kind of detail was Arthur. I think that's why they became friendly."

Having received a commission from Geoff Travis at Rough Trade, Russell also asked Gibbons to remix "Let's Go Swimming". "There were incredible scenes of screaming and fights," says Gary Lucas, who oversaw the recording process, which began at eleven-p.m. and wound up at eight the following morning. "Arthur was shrieking and tearing his hair out, raging around the studio like a psychotic bat, while Walter was calmly snipping and pasting the tape as if it was macramé." There were streams of tape all over the studio. "Arthur would say, 'You're ruining my fucking vision!' And Walter would reply, 'Arthur, Arthur, calm down!'"

"Mixed with Love by Walter Gibbons", the Coastal Dub version of "Let's Go Swimming" was less song-oriented and more conceptual than the Gulf Stream Dub and the Puppy Surf Dub, both of which were completed by Russell. As with so many Gibbons mixes, the track was constructed over a bongo beat, although on this occasion the rhythm was never allowed to settle into a groove, but instead lurched from beat to beat, with Russell's manic synthesiser riff rolling over a rumbling bass and cello. "Walter created a visionary soundscape for the song," says Lucas. "He took the song out to the stratosphere."

Two other Gibbons remixes were released in this twilight period: "4 Ever My Beat" by Stetsasonic, which came out on a Tommy Boy double pack, and "Time Out" by the Clark Sisters, which was released on Rejoice/A&M. Steering an uneasy path between synthesizer pop, jagged beats and run-of-the-mill gospel, the "Time Out" mix encapsulated the conundrum of combining feel-good vocals with a left-of-leftfield sensibility. Gospel Gibbons' ever more angular vision didn't sit easily with gospel.

The message was a lot simpler to communicate from behind the counter at Rock and Soul, situated on Seventh Avenue between Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth Streets, where Gibbons sold records and dished out sermons with equal gusto. Saxophonist Peter Gordon, another Russell collaborator, became the recipient of one particularly violent tirade when he handed Gibbons a copy of "That Hat", the B-side of which was titled "The Day The Devil Comes To Get You".

During this period Gibbons amassed a collection of approximately five thousand gospel records, many of which were signed copies purchased directly from church congregations in New York. "He thought gospel was the pure message of God and that something was wrong with you if you didn't get it," says Krivit, an occasional customer. "Every time he opened his mouth he would preach at you. It seemed to a lot of people he was just history, especially as there was less of a nostalgia thing going on at the time."

Yet ever since Bobby "DJ" Guttadaro, Francis Grasso and David Mancuso started to push Dorothy Morrison's "Rain" at the turn of the 1970s, gospel had demonstrated its ability to heighten the celebratory mood of the dance floor, and Gibbons continued to unearth the occasional treasure, including "Stand On The Word", which was recorded live in the First Baptist Church in Crown Heights in 1982.

"'Stand On The Word' was Walter's biggest record at the time," says Gate, who visited the church in order to track down the origins of the song. "The record was recorded in his local church -- the Jus Born studios were only a couple of blocks away. Walter played this record after the church pressed up a couple of hundred copies for the congregation." The song soon became a Garage, Loft and Zanzibar classic, and Tony Humphries went on to remix the record -- which was attributed to the Joubert Singers, after Phyllis McKoy Joubert, who penned the song for the Celestial Choir -- for Next Plateau. For many, Gibbons had lost his way but not his ear.

* * * * *

Walter Gibbons might have started to preach the Gospel with even more vigour after discovering he had contracted the Aids virus sometime in the second half of the 1980s. For a while nobody could tell he was sick: after all, Gibbons had always looked undernourished. But as the disease progressed, there could be no mistaking its presence. "I saw him at Rock and Soul about a year before he passed away," says Bob Blank. "He was in terrible shape. He was very thin and had lost a lot of his hair. He looked around and said, 'I just love being in contact with music. This is what I love.'"

Knowing that his corporeal end was near, and riding on the back of a new wave of interest in disco's pioneering DJs and remixers, Gibbons embarked on a mini-tour of Japan, where he played at the Wall (Sapporo) and Yellow (Tokyo) in September 1992. Mixing classics, house and hip-hop with his treasured reel-to-reels, he was received enthusiastically by local DJs and music aficionados. In between appearances, Gibbons went to listen to Larry Levan and François Kevorkian, who were playing at Gold as part of their Harmony tour. According to DJ Nori, Gibbons loved Japan and wanted to live in Sapporo.

Gibbons returned to Japan in 1993. Eyewitnesses say he was skinny but radiantly happy -- so happy that, during one of his nights at Yellow, he refused to stop playing when police raided the club and ordered it to close. The night was eventually reconvened as a private event and the party hit a new high, with Gibbons channelling his entire soul into the music. At the end of the set he asked to be taken to Hakone and, when he finally saw Mount Fuji, he kept uttering, "It's beautiful. It's beautiful!" He was subsequently whisked to a hot spring where he was able to revitalise his tired body.

Gibbons played his final set in New York at Renegayde, a monthly night organised by Joey Llanos and Richard Vasquez. Drawing on sixties Motown, Philly Soul, disco, early eighties dance and contemporary house, the ex-Galaxy spinner took his dancers on a timeless voyage of devotion and love, sequencing his selections according to ambience rather than chronology or genre. Gibbons demonstrated little in the way of turntable pyrotechnics but stretched the metaphor of the DJing journey to breaking point. Sincerity was more important than dexterity.

Aware that Gibbons regarded himself as an instrument of God, DJ Cosmo, who attended the Renegayde gig, wasn't sure if she had "heard Walter play" or if it was "God on the decks that night." Either way, Gibbons' "pure and beautiful musical aura" provided a striking contrast with the freakish mood of the post-Garage club scene. "I was really struck by Walter's honesty to himself, to his faith and to his audience."

DJ-producer Adam Goldstone, who also went to the party, admired the way Gibbons created an "uplifting, spiritual and positive atmosphere" without slipping "into religious proselytising or the kind of lazy, saccharine clichés that seem to pass for soulful dance music these days." The vibe in the room was electric. "I think everyone at the party realised they were sharing in something special."

Nightworld was war-wearily accustomed to seeing Aids devour its favourite sons and by the time of the Renegayde party it was clear that Gibbons would soon follow. "Walter was looking very thin," says Quinton Deeley, a London-based New York dance enthusiast. "He was obviously in poor health. It was poignant to see him play so well despite his advanced illness." Renegayde turned out to be the DJ's last public performance.

Frail, isolated and all but blind, Gibbons started to go out to Beefsteak Charlie's with François Kevorkian and Tom Moulton every Tuesday night. "A lot of people abandoned Walter, but he wasn't the most outgoing person either, and he didn't attract a lot of friends," says Moulton. "We would help him down the stairs. Beefsteak Charlie's had a salad bar and shrimp, all you could eat, and watching Walter shovel down that shrimp, I don't know where he put it. He kept saying, 'Boy, this shrimp is so good!'"

Gibbons continued to play records until the very end -- Moulton says the ex-Galaxy DJ developed a special "notch system" in order to recognise his records by touch -- and when he learnt that Moulton had just finished remastering a series of Salsoul twelve-inches he asked him to try and get hold of an advance copy. No tests were ready, so Ken Cayre put through a special set, which Moulton took to his old sparring partner. "Walter played one and said, 'Oh, it sounds great!'" remembers Moulton. "Then he cued up another record and mixed it in perfectly. He was a DJ to the very end."

Having spent his final weeks living alone in a YMCA, Gibbons died of complications resulting from Aids on 23 September 1994, aged thirty-eight years old. One of his final acts was to donate his record collection to an Aids charity based in San Francisco. Only a small number of people attended his funeral, and his memorial service, a dignified affair held on 11 October at the Church of St. John the Baptist on Thirty-first Street, was also relatively quiet -- much more quiet than the equivalent service held for Levan in 1992. Billboard marked the moment with a brief obituary at the bottom of its weekly dance music column. Devastatingly shy to the end, Gibbons might have been happy to pass away without too much of a fuss.

Yet we can forgive ourselves a certain amount of frustration that this groundbreaking remixer and DJ hasn't received more attention during the ongoing revival of interest in the disco decade. The name of Gibbons rarely features alongside canonical seventies spinners such as Francis Grasso, David Mancuso, Nicky Siano, Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles, even though it is difficult to think of a more accomplished or visionary mixmaster. And as a remixer he has received significantly less attention than Tom Moulton, François Kevorkian and Larry Levan, even though he was arguably the most influential of them all when it came to establishing the future contours of remixology.

According to Blank, Gibbons was in a league of his own in the studio. While most remixers would enter unprepared, Gibbons would always do his homework, and while most remixers would bark out instructions, Gibbons would always sit with his hands on the mixing board. Yet the thing that most impressed Blank was the DJ's intuitive outlook. "It was quite easy to chop up a record and extend certain sections," says the engineer. "The difficult thing was to take a multitrack and create a flow. The skill lies in feeling the music and that's what Walter could do. He would sit at the board with the mute buttons, and he would cut and edit in real time."

Gibbons took the art of remixing to an emotional level. "He would come in and say, 'I want this song to be the love mix,'" remembers Blank. "He would listen to the bass part and say, 'That part is really about love.' These are amazing concepts. That's totally different to someone who comes in and says, 'I've got to get this mix out in a day and we've got to have three breaks!'" Gibbons was nurturing a new affective sensibility. "He would say, 'I want the flow to be like this, and just when you think you've hit this peak I want to go back into the groove.' Nobody was doing that. It was an amazing way of working."

When it came to plunging into a multitrack and excavating its core energy, Gibbons wasn't just the best: he was also the first. "By the time Larry came by I had done a thousand dance records," adds Blank. "I knew what was supposed to happen. I didn't say, 'Oh my God, there's the bass drum!'" It was different with Gibbons. "Nobody had heard the strings all by themselves or the rhythm chopped into these syncopated moments, but once he did it people began to understand there was a formula. When the next person came in after Walter, I would bring up all of his good ideas. That was my job -- to remember all the cool things."

The point is not to elevate Gibbons in order to denigrate others. Rather, it is to acknowledge that, at least for a few years, he was streets ahead of his contemporaries. As a breakbeat DJ working with reel-to-reel tapes, he at least paralleled and arguably anticipated core aspects of hip-hop culture. And as a remixer producing stripped down tracks that shifted between insistent beats and floating instrumentation, he developed an early blueprint for house. Gibbons was the first DJ to move into the protected world of the studio, and in the second half of the seventies and the first half of the eighties there were only three DJ remixers who really mattered: Gibbons, Kevorkian and Levan. Gibbons was the first.

Yet if there was a potential flaw with Gibbons' practice, it lay in the unrelenting purity of his vision. "Walter was an innovator, but he also had an abstract I don't give a shit approach," says Kevorkian. "Walter didn't care if anyone danced, whereas Larry would make it for the party. He was a little more conscious of what people liked. Whereas Walter was conceptually the most advanced, he was also a lonely genius. Walter was an innovator, but Larry made it work. He turned records into hits."

Scattered but not discarded, a series of unreleased Gibbons mixes continue to levitate around the outer reaches of the dance ether. Jeremy Newall spotted a reel of "Making Love Will Keep You Fit"/"Freakin' Freak" by Brenda Harris (Dream Records), marked "mixed by Walter Gibbons", in Tom Moulton's office in New York. Somewhere, surely, there is a copy of "Faith", the track Gibbons mixed and produced with Steve D'Acquisto (referenced by Steven Harvey in his Collusion article). And then there is the mouth-watering prospect of that "Go Bang" remix.

Some "lost recordings" are beginning to surface. Audika released Arthur Russell's "Calling All Kids", "remixed with love" by Gibbons some time between 1986 and 1990, earlier this year. And Colin Gate, who purchased the key elements of Gibbons' record collection when it was eventually returned to Rock and Soul, is hoping to release a collection of Gibbons' unreleased acetates, mixes and songs. "Walter's acetates are much more intense than his Salsoul remixes," says Gate. "You can hear slices of his DJing style on remixes like 'Just As Long', where there's that looped section with a kick drum and hi-hat pattern with a clap. Some of his acetates extend that house sound for ten minutes, not just a few bars."

Marking the tenth anniversary of Gibbons' death, this Suss'd compilation brings together his groundbreaking Salsoul catalogue for the very first time and, considered as a collection, the remixes create an indelible impression. These mixes could barely be contained on three CDs, whereas the equivalent Levan compilation barely stretched to two, and the quantity of the ex-Galaxy DJ's output in no way detracts from its quality.

"Compared to the Larry Salsoul compilation on Suss'd, Walter's mixes are more groundbreaking and seem to demonstrate a very hands-on type approach," says DJ/Salsoul aficionado Jeremy Newall, who helped compile both CDs. "It was probably Larry's personality, the size of the Garage, and the success of records like Taana Gardner and the Peech Boys, as well as his obvious DJ talents, that made him the deity he is today." Gibbons might be about to receive a little more recognition himself. "Hopefully this package will bring a lot more respect to Walter. It is deserved, without any doubt."

These remixes would have surely been reissued long before now were it not for Gibbons' conversion. Yet there is also a peculiar proximity between the DJ-remixer's evangelism and the practices that continue to underpin Nightworld to this day. Definitively fervent, DJs try to convert anyone who will listen to their favourite records, while dancers enter into a quasi-religious ritual in which they and their priest-like spinners generate a collective, spiritual high.

Gibbons experienced both sides of this divide -- dance floor spirituality on the one hand, born-again Christianity on the other -- and magnified the continuum that exists between them. Magical and evangelical from the beginning to the end, he lived and died in music. The spirit of his remixes, all of them mixed with love, will continue to move and shape dance floors for the rest of time.

Thanks:

Chidi Achara, Chris Barnett, Bob Blank, Kenny Carpenter, Ken Cayre, Denise Chatman, Quinton Deeley, Ian Dewhirst, Allan Felder, Adam Goldstone, Yuko Ichikawa, Jellybean, JJ, Dr Bob Jones, François Kevorkian, Gary Lucas, Danny Krivit, Cedric Lassonde, Colleen "Cosmo" Murphy, DJ Nori, Alex Pe Win, Steve Reed, Alex Rosner, Will Soclov and, especially, Colin Gate, Niki Mir, Jeremy Newall and Tony Smith.