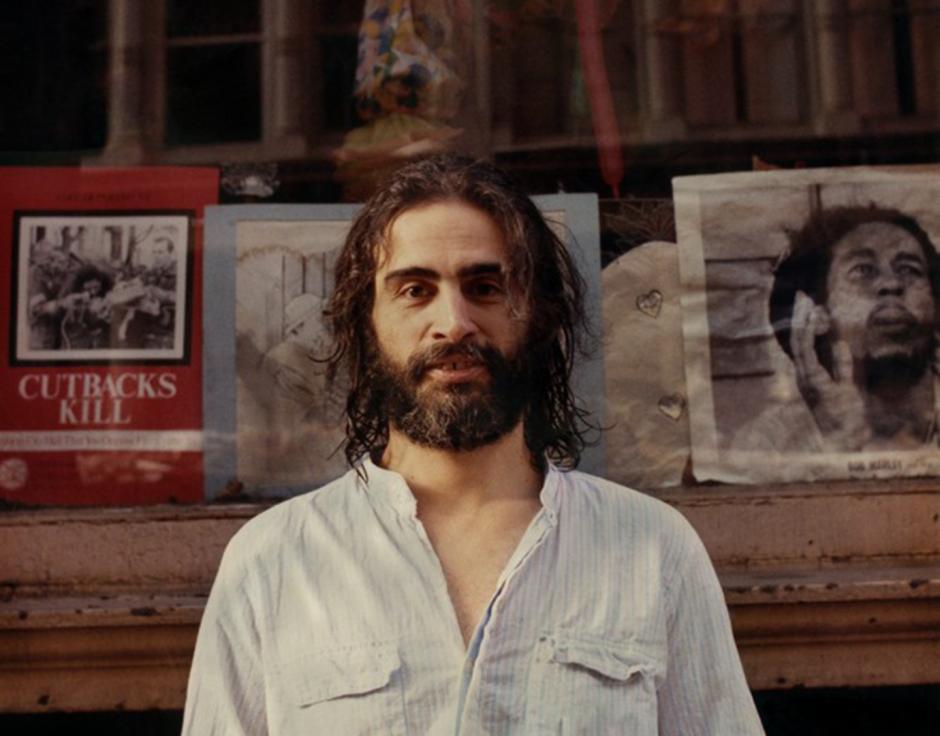

David Mancuso outside Prince Street Loft, New York, 1988. Photo by Pat Bates

Disco historian Tim Lawrence, author of Love Saves The Day, remembers the late party purist's selection policy at parties in New York, London and Sapporo

David Mancuso made an incomparably profound contribution to the development of contemporary party culture. His vision was the simplest one he or anyone who knew him could imagine, and it inspired many. Yet as the culture stretched out his vision of the role of music within party culture went through turns and somersaults, a number of which took it to the point where it was barely recognisable to Mancuso. In ways that could seem dogmatic yet ultimately resonate as being profoundly ethical, insightful and even mystical, he barely wavered from his original vision during an unprecedented run that dates back to Valentine’s Day 1970. Inevitably he made some false turns as he made his way, yet any deviation only led him back to a path already established. When he passed away a week ago he left a legacy that was almost monk-like in its purity.

Mancuso’s musical philosophy placed music as a central component in a universe that in essence amounts to an unfolding party. Shaped through experiences that ranged from growing up in a children’s home to participating in the kaleidoscopic energies of the countercultural movement, he began to host private parties that combined the Harlem rent party tradition, audiophile stereo equipment, Timothy Leary’s LSD gatherings and downtown loft living with music capable of providing a form of life energy to enable his social gatherings to go further in their journey towards communal-transcendental transformation. Not even Francis Grasso, whose work at The Sanctuary paralleled Mancuso’s early efforts, was this far advanced. And Mancuso was only just starting out.

Prior to Mancuso, DJs were paid to “work the bar”, or whip crowds into a hurried frenzy before “killing the floor” with a slow number that contained the subliminal lyrics “It’s time to drink now”. There was no conversation, no flow. But Mancuso went about his work in the privacy of his own home, not a public space, and with alcohol set aside for the kind of stimulant whose initials inspired him to write “Love Saves the Day” on invitations to his February 1970 gathering, he was able to select music in relation to the energy of his dancing guests. The result amounted to a form of collective, democratic, participatory, improvised music making that was rooted in antiphonal conversation rather than virtuoso monologue. The practice of dancing to pre-recorded music had taken a great leap forward and there could be no shuffling back.

From that night onwards, Mancuso introduced an improbably wide range of sounds into the New York City party scene, with selections such as War’s “City, Country, City” , Chicago’s “I’m A Man” , Eddie Kendricks’s “Girl You Need A Change Of Mind” and Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa” becoming elements in a sonic tapestry that wove in Latin, African, rock, gospel, breakbeat and even country while prioritising explorative records that reached dramatic crescendos. The discovery that long records enabled the party to enter into a deeper socio-psychic plane spearheaded a collective desire that culminated in the innovation of the 12" single. Meanwhile Mancuso placed records on the turntable according to the signs and signals of his dancing guests, conscious that a ‘third ear’ combining the consciousness of everyone gathered would ultimate lead to a journey that loosely followed the three bardos of intensity outlined by Leary in his notes on the acid experience.

The practice of mixing between two records – a technique pioneered by Grasso at the Sanctuary – seemed somewhat insignificant within the context of The Loft, as guests came to name Mancuso’s parties. Instead Mancuso remained more interested in the way records could be knitted together according to instrumental signatures, lyrical themes, production values and energy patterns to form an unfolding journey that by the early 1980s could last for up to 18 hours. The means of segueing from one record to another was just a technical matter that shouldn’t become more important than the music itself.

Mancuso related to music within an ethical framework that sought to bring social progress to the world, albeit on a local level. He co-founded the first record pool, the New York City Record Pool, in order to help his peers receive free copies of records to play/promote without record company support. He refused to play bootlegs on the basis that the original artists wouldn’t get their share of the sale. He declined to speak of his music selections or his playlists, preferring to attribute everything to the collective endeavour of The Loft. When asked about his approach to playing records, he’d wonder about the premise of the question because the truth of the matter was he couldn’t even play a musical instrument. He kept sound levels to 100dB because anything louder might damage the ears of one of his guests, and why would he want to harm someone entering a social situation?

In order to take the party deeper and higher, Mancuso devoted much of his life to the perfection of The Loft’s sound system. He introduced audiophile stereo components from the get-go, and by the late 1970s had established the core element of a system that included Klipschorn speakers, Mark Levinson amplifiers and Koetsu cartridges. Early into The Loft’s run he also hired sound engineers Alex Rosner and Richard Long to respectively design tweeter arrays and bass reinforcements that enabled him to give records a frequency injection at key moments in the party, yet he ditched the kind of innovations that later became a major feature of discotheque sound system design aftter concluding that music was perfectly capable of speaking for itself when channelled through a sufficiently accurate system.

Such was his faith in the emancipatory power of music, Mancuso even removed the mixer from his set-up in the early 1980s, finally convinced that such equipment introduced unnecessary stages in the electronic circuit that lay between the needle and the loudspeaker. Why only go 97 per cent of the way up a mountain when you can reach the summit, Mancuso once asked me. Ultimately he came to believe that the system’s sole purpose was to reproduce the original recording as precisely as possible so that the music would “play us”.

From the very beginning through to the very end Mancuso thought of himself as a musical host rather than a DJ. His reasoning was simple. Whereas DJs usually operated as for-hire freelancers who entertained crowds by deploying a set of technical skills, Mancuso was the host of an entire party, an entire environment, with music just one of his responsibilities. Indeed he lacked the technical skills that most DJs could draw on, didn’t get paid for his work, and didn’t even see himself as an entertainer. Rather, he compared himself to the host of a rent party who in less developed settings turned to a record player tucked away in the corner of the room in order to give guests something to dance to. And while the peerless clarity of his sound system threatened to bestow authority upon Mancuso, he remained firm in his mind that the newfound power of music confirmed his humble place in the universe. As he told me in an interview conducted in 2007:

“I’m just part of the vibration. I’m very uncomfortable when I’m put on a pedestal. Sometimes in this particular business it comes down to the DJ, who sometimes does some kind of performance and wants to be on the stage. That’s not me. I don’t want attention I want to feel a sense of camaraderie and I’m doing things on so many levels that, whether it’s the sound or whatever, I don’t want to be pigeonholed as a DJ. I don’t want to be categorised or become anything. I just want to be. There’s a technical role to play and I understand the responsibilities, but for me it’s very minimal. There are so many things that make this worthwhile and make it what it is. And there’s a lot of potential. It can go really high.”

Save for the creation of the New York City Record Pool, Mancuso remained remarkably focused on his own parties, perhaps because the countercultural movement’s wider aspiration to change the world had in many regards ended in disappointment, with state repression playing a significant part. Yet the power of his parties attracted a dedicated crowd of dancers as well as a significant number of discotheque DJs, who’d head to The Loft once they were done for the night, and although each step only amounted to a baby step, by the end of the decade it would be possible to cite The Loft as the most influential party of its era. Many of the most influential party spaces – private parties such as The Tenth Floor, The Gallery, Flamingo, 12 West, The Soho Place, Reade Street, The Paradise Garage and The Warehouse – were modelled directly or vicariously on The Loft. Meanwhile many of the most influential DJs and remixers of the period – Larry Levan, Frankie Knuckles, Nicky Siano, François Kevorkian, David Morales, Tony Humphries – absorbed the “Love Saves the Day” vibes as they headed to The Loft on a regular basis. Even if he sometimes wondered about the way his model was adapted in some situations, especially when exclusionary policies crept in, Mancuso was largely happy for the message to spread. It’s like a good joint, he once told me, you pass it around.

Mancuso’s belief in the centrality of the party versus the musical host/DJ received its ultimate test when he was unable to play at a party himself. The first time this happened in London, where he had started to co-host events with myself, Colleen Murphy and Jeremy Gilbert, Colleen was able to step in seamlessly. The parties in London as well as Sapporo, Japan, also continued with barely a hiccup when a doctor suggested to David that he stop travelling internationally a few years later. Around this time David had started to effect an incremental, monk-like withdrawal from his own parties. The result is that, at the time of his passing, David had overseen the creation of three Loft parties in three cities that had been running for 46, 16 and 13 years respectively and were all set to continue along the purist lines he had maintained for a lifetime. He had fulfilled the dream of being able to disappear in the middle of a beautiful party.

As he told me in an interview: “I don't want to go into the ‘I won’t always be here’ thing, but if I’m not here tomorrow, we now know what to do and what not to do.”

Lucky Cloud Sound System party in London. Photo by Tim Lawrence