Despite the late 1970s national backlash against disco, dance culture flourished in New York during the first years of the 1980s, but entered a period of relative decline across the second half of the decade when a slew of influential parties closed. Critics attribute the slump to the spread of AIDS, and understandably so, for the epidemic devastated the city’s dance scene in a way that began with yet could never be reduced to numbers of lost bodies (Brewster and Broughton, Buckland, Cheren, Easlea, Echols, Shapiro). At the same time, however, the introduction of a slew of neoliberal policies—including welfare cuts, the liberalization of the financial sector, and pro-developer policies—contributed to the rapid rise of the stock market and the real estate market, and in so doing presaged the systematic demise of dance culture in the city. In this article, I aim to explore how landlords who rented their properties to party promoters across the 1970s and early 1980s went on to strike more handsome deals with property developers and boutique merchants during the remainder of the decade, and in so doing forged a form of “real estate determinism” that turned New York City into an inhospitable terrain for parties and clubs.1 While I am sympathetic to David Harvey’s and Sharon Zukin’s critique of the impact of neoliberalism on global cities such as New York, I disagree with their contention that far from offering an oppositional alternative to neoliberalism, cultural workers colluded straightforwardly with the broad terms of that project, as will become clear.

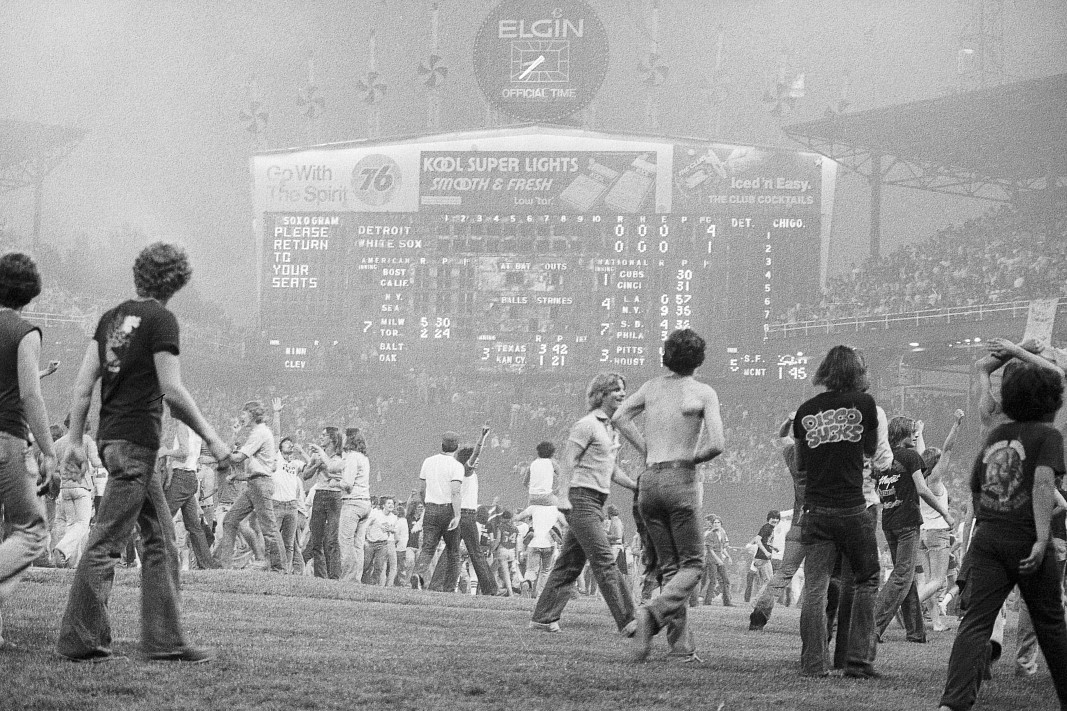

The dance culture that I want to discuss can be traced back to the beginning of 1970, when parties such as the Loft and the Sanctuary pioneered the weekly practice of all night dancing that would go on to be labeled (somewhat problematically) “disco.”2 Initially off the radar, the movement became highly visible following the opening of Studio 54 in midtown Manhattan in April 1977 and the release of the movie Saturday Night Fever later that year. Disco achieved mainstream saturation across 1978—thousands of discotheques opened and the genre outsold rock—only for the combination of the overproduction of the sound and the slowdown in the US economy across 1979 to generate a homophobic, racist, and sexist backlash against the culture. Led by the Chicago radio DJ Steve Dahl, the anti-disco movement highlighted the angst felt by white straight men about their increasingly uncertain future, and their perception they were losing ground to gay men, women, and people of color (or the alliance of dispossessed citizens that lay at the heart of the 1970s dance network). The “disco sucks” campaign, then, captured the crisis that enveloped the United States as disillusioned citizens sought out scapegoats to blame for the exhaustion of the postwar settlement, and picked on discophiles along with 1960s countercultural activists for leading the country into a cycle of supposedly unproductive hedonism.3 However, while the consequences of the backlash were far-reaching in terms of the number of dance venues that closed down nationally, as well as the cuts that were executed in disco departments across the music industry, New York City’s dance network was largely unaffected, and the independent record company sector that served it only temporarily troubled.

Downtown’s private parties survived with ease. “I read about ‘disco sucks’ in the paper and that was it,” comments David Mancuso, host of the Loft, the original downtown private party. “It was more of an out-of-New York phenomenon. New York was and remains different to the rest of the States, including Chicago. Out there they had this very negative perception of disco, but in New York it was part of this mix of cultures and different types of music.”4 Opened in stages across 1977 and 1978 as an expanded version of the Loft, the Paradise Garage thrived alongside Mancuso’s spot, especially when owner Michael Brody turned Saturdays into a gay male night (with a female and straight presence), and maintained the already successful Friday slot as a mixed night. Flamingo, which catered to an elite white gay male crowd, and 12 West, which attracted a more economically diverse gay male membership, also prospered until the theater and bathhouse entrepreneur Bruce Mailman opened the Saint on the site of the old Fillmore East at the cost of $5,000,000 in September 1980. Sporting a spectacular planetarium dome above its dance floor, the Saint started to attract 3,000–4,500 dancers every Saturday from opening night onwards.

Public clubs proliferated across the same period. Among the new spots, the Ritz opened as a rock-oriented discotheque that showcased live bands, the colossal Bonds switched to a similar format when its original owners become embroiled in a tax scandal, Danceteria operated as a supermarket-style entertainment spot that dedicated separate floors to live music, DJing, and video, and the Pyramid Cocktail Lounge took off as bar and dance venue that prioritized new wave, performance art, and East Village drag. Forging a more overtly multicultural aesthetic, the Funhouse caught on around the same time when Jellybean Benitez was hired to DJ at the spot, and drew in a huge Italian and Latin crowd. A short while later, Ruza Blue’s Wheels of Steel night at Negril and then the Roxy offered a mix of funk, rap, electro, dance, and pancultural sounds. Meanwhile the Mudd Club continued to integrate elements of punk and disco in its mix of DJing, live music, art exhibitions, and fashion shows, and Club 57 maintained its spirited combination of whacky parties, performance art, and film screenings. A number of these spots displayed the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Futura 2000, Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and other young artists who could not find a way into SoHo’s already sedimented gallery scene, and gave them jobs if they needed to supplement their income.5 As such, they operated as inclusive, self-supporting communities that forged a cooperative ethos that contrasted with the neoliberal logic of exploitation, division, and maximum profit.

Liberated by the decision of the major record companies to withdraw from dance along with the loosening up of audience expectations in the postdisco period, independent record companies such as Island, 99 Records, Prelude, Sleeping Bag, Sugar Hill, Tommy Boy, and West End also thrived across the early 1980s. Together they reestablished the position independent labels enjoyed in the mutually supportive network that defined the relationship between dance venues, dancers, and recording studios across much of the 1970s, and although few of their releases went on to achieve a national sales profile, the independents were able to thrive on locally generated club-based sales that would often run into the tens of thousands. Paradise Garage DJ Larry Levan enjoyed his most prolific and creative period as a remixer between 1979 and 1983, and along with figures such as Arthur Baker, Afrika Bambaataa, François Kevorkian, Shep Pettibone, and John Robie, Levan contributed to the creation of a chaotic, mutant milieu that drew the sounds of postdisco dance music, rock, dub, and rap into a sonic framework that was increasingly electronic.

While late 1970s disco producers recorded within the constraints of an increasingly demarcated and rigid format, early 1980s dance producers conjured up cross-generic combinations that drew explicitly from rock, dub, and rap. In the case of “Don’t Make Me Wait” by the Peech Boys, bandleaders Michael de Benedictus and Larry Levan introduce cluster storms of echo- heavy electronic handclaps around which a thick, unctuous bass line splurges out massive blocks of reverberant sound, vocalist Bernard Fowler channels soul music’s routinized theme of sexual attraction through the erotically charged, transitory environment of the Garage floor, and guitarist Robert Kasper plays hard rock. On another contemporaneous release, David Byrne’s “Big Business” explores the connections that ran between new wave, funk and dance while delivering elliptical lyrics that appeared to warn against the country’s rightwards shift. “Over time disco became less freeform and more of a formula, and the arrangements also became less interesting,” notes Mancuso of the shifting sonic terrain. “There were fewer and fewer good records coming out. It was obvious there would have to be a change. People didn’t want a set of rules. They wanted to dance.”

Neoliberalism and Downtown Culture

The shift to a neoliberal agenda can be traced back to the moment when the banking sector began to exert an explicit grip on New York in the mid-1970s. Unable to repay its short-term debts as a result of the decline of its industrial manufacturing sector and the flight of white taxpayers, New York’s government was compelled to strike a harsh deal that led to 65,000 redundancies, a wage freeze, welfare and services cuts, public transport price hikes, and the abolition of free tuition fees at the City University in return for a bailout (Newfield and Barret 3). In the eyes of free-marketeers, the city that had come to symbolize the intractable waste of the 1970s became a model of neoliberal adventure. “The management of the New York fiscal crisis pioneered the way for neoliberal practices both domestically under Reagan and internationally through the IMF in the 1980s,” comments David Harvey in A Short History of Neoliberalism. “It established the principles that in the event of a conflict between the integrity of f inancial institutions and bondholders’ returns on the one hand, and the well-being of the citizens on the other, the former was to be privileged. It emphasized that the role of government was to create a good business climate rather than look to the needs and well-being of the population at large” (48).

A committed Carter supporter, Mayor Ed Koch had little choice but to accept the environment of extreme financial restraint when he assumed office in 1978. Yet rather than emphasize his opposition to the settlement, or seek to introduce policies that would support the poor rather than the interests of large corporations, Koch embraced the fiscal restraints imposed on New York City with the zeal of a born-again bank manager. As Jonathan Soffer notes in his biography of Koch, the mayor’s inaugural speech “reflected a neoliberalism that was far more concerned with ‘business confidence’ than with aff irmative action,” and concluded that the “city had been too altruistic for its own good, leading to mistakes ‘of the heart’” (146). Koch made gentrif ication “the key to his program for New York’s revival,” adds Soffer (146), and went on to construct a governing coalition of “real estate, f inance, the Democratic Party machine, the media, and the recipients of city contracts,” comment Jack Newfield and Wayne Barrett (3). Struggling with the burden of a $1.8 billion debt in 1975, the city went on to produce a budget surplus ten years later thanks to strong economic growth. “At the same time,” note Newf ield and Barrett, “the poor were getting poorer, for the boom of the 1980s bypassed whole chunks of the city” (4).

At the national level, Jimmy Carter preempted Reagan’s embrace of neoliberalism by introducing deregulation into not only the gas, oil, airline, and trucking sectors, but also the increasingly powerful banking sector (this via the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980). Adding electoral positioning, revisionist history, the conviction of class interests, and affective reassurance to the mix, Reagan delivered a series of speeches and policy statements that aligned him with the so-called traditional voting constituencies that Carter had failed to favor: he characterized the countercultural coalition of the late 1960s as the cause of the country’s demise during the 1970s; he seized on policy developments around deregulation and welfare cuts not as a requirement but as an opportunity to unleash market-driven wealth at the expense of greater equality; and he embodied a form of brill-creamed 1950s conservatism that reassured many that these radical economic and social changes would help reestablish the country to its supposedly golden past.6 William K. Tabb maintains in The Long Default that the Reagan administration became “merely the New York scenario” of the 1970s “writ large” (15), the main difference being that Reagan lacked Koch’s progressive instincts around healthcare, gay rights, and other so-called liberal issues.

Along with the wave of artists, choreographers, composers, ex- perimental video filmmakers, musicians, performance artists, sculptors, and writers who gravitated to downtown New York during the 1960s and 1970s, the party hosts and promoters who operated in the East Village, the West Village, and SoHo appeared to be threatened by these developments. After all, they moved to the area because space was cheap, which in turn meant they could live in a community that was organized around creative work that put a low value on commerciality. As a result, they pursued unlikely interdisciplinary and cross-media projects, exchanged favors around performances, valued ephemeral art over the production of objects that could be sold, and forged a network that was notable for its integration and level of collaboration. “Artists worked in multiple media, and collaborated, criticized, supported, and valued each other’s works in a way that was unprecedented,” notes Marvin J. Taylor in The Downtown Book . “Rarely has there been such a condensed and diverse group of artists in one place at one time, all sharing many of the same assumptions about how to make new art” (31).

If the probusiness, progentrif ication policies of Koch and Reagan broke up that network, it would have made sense for politicians and cultural producers to be strategically opposed to one another. However, Sharon Zukin argues in Loft Living: Cultural and Capital in Urban Change that in fact the cultural producers forged an alliance with real estate investors and the city government in order to drive out industrial manufacturers from SoHo and other loft-rich areas. “Before some of the artists were chased out of their lofts by rising rents, they had displaced small manufacturers, distributors, jobbers, and wholesale and retail sales operations,” Zukin writes. “For the most part, these were small businesses in declining economic sectors. They were part of the competitive area of the economy that had been out- produced and out-maneuvered, historically, by the giant f irms of monopoly capital” (5).7 Zukin adds: “The main victims of gentrif ication through loft living are these business owners, who are essentially lower middle class, and their work force” (6).8 Of the 1975 amendment to the Administrative Code of the City of New York, Zukin argues: “With J-51 [the amendment], the city administration showed its irrevocable commitment to destroying New York’s old manufacturing lofts” (13). And in the postscript to the UK publication of the book, published in 1988, Zukin concludes: “With hindsight, and with the bittersweet taste of gentrif ication on every urban palate, it is not so diff icult to understand the ‘historic compromise’ between culture and capital that loft living represents” (193).

David Harvey develops the argument that cultural producers and capital colluded across the 1970s and 1980s in A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Indeed, Zukin notes that Harvey’s 1973 book Social Justice and the City inspired the analytical approach of Loft Living, and having written the introduction to that book, Harvey expounds on its central thesis; that far from being politically progressive, cultural workers became inseparable from the neoliberal project across the 1970s and 1980s. “The ruling elites moved, often factiously, to support the opening up of thecultural field to all manner of diverse cosmopolitan currents,” he writes, “The narcissistic exploration of self, sexuality, and identity became the leitmotif of bourgeois urban culture. Artistic freedom and artistic licence, promoted by the city’s powerful cultural institutions, led, in effect, to the neoliberalization of culture. ‘Delirious New York’ (to use Rem Koolhaas’s memorable phrase) erased the collective memory of democratic New York.” Harvey adds that a conservative distrust of the demographic make-up and outlook of artistic types caused ripples of dissent that were usually drowned out in the pursuit of prof it. “The city’s elites acceded, though not without a struggle, to the demand for lifestyle diversif ication (including those attached to sexual preference and gender) and increasing consumer niche choices (in areas such as cultural production),” adds Harvey/“New York became the epicentre of postmodern cultural and intellectual experimentation” (47).

Harvey’s and Zukin’s analysis is reasonable insofar as a number of cultural workers purchased their loft apartments and went on to make signif icant prof its on selling their properties, having contributed to the gentrif ication of the area. In addition, some went on to prof it from the market-led rejuvenation of New York’s economy through the sale of their works and the receipt of sponsorships from the benef iciaries of the neoliberal boom, from Wall Street brokers to public institutions that were charged with the role of marketing New York as a global center of cultural tourism. However, both Harvey and Zukin overstate the collusion inasmuch as only a tiny proportion of cultural workers could have moved downtown in order to participate in a self-conscious project of gentrif ication, while many lived in small apartments in the East Village because even the low rents of SoHo, TriBeCa, and NoHo were prohibitive. In addition, Harvey and Zukin underemphasize the experience of the vast majority of those workers, who were carved out of SoHo’s gallery economy from an early moment, and were compelled to leave the area in signif icant numbers when rents went up.9 While some of the work of the downtown artists was suitable for co-option by the sponsors of neoliberalism, a far greater proportion was grounded in collaborative, noncommodif iable practices that could not be sold in any straightforward way. Along with Harvey, Zukin mourns the shift from industrial to postindustrial capitalism, yet inexplicably attributes this to the existence of cultural workers when she argues that they “displaced” industrial manufacturers, or ousted them forcibly, even though the artists moved into empty lofts that had been evacuated by industry, either because those businesses had moved to areas that were more favorable than downtownNew York, or because they had succumbed to the national decline in the industrial sector. That could hardly be attributed to a relatively small group of cash-poor creative types.

New York’s downtown dance scene might have been post-Fordist in its co-option of ex-industrial buildings, yet its core ritual was anything but neoliberal, rooted as it was in the anti-individualist ethos of the dance floor, where dancers abandoned the self in pursuit of collective pleasure, often in settings that encouraged the kind of “inter-class contact” advocated by Samuel R. Delany in his book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (111). Indeed owners and promoters disregarded the prof it motive consistently, with David Mancuso and Michael Brody notable for spending huge sums of money in pursuit of perfect sound, Jim Fouratt and Rudolf Pieper for reinvesting Danceteria’s takings into risk-taking programs and costly interior redesigns, Bruce Mailman for seeking a degree of experiential perfection that left his investors dissatisfied, and so on. Moreover, whereas the arrival of artists contributed to the regeneration of SoHo and other downtown neighborhoods, the existence of dance venues, and in particular those that attracted a heavily gay and ethnic presence, was deemed to counter the gentrification process by local residents (who opposed Mancuso’s move from NoHo to SoHo, for example). Nor did neoliberal wealth trickle down to the protagonists of the New York dance scene. “All this money came into New York, and it was like, ‘Give all the money to the rich people and it will trickle down to the little guy.’ But that never happened,” notes Ivan Ivan, a DJ at the Mudd Club and Pyramid. “Money was coming into New York, but it was being enjoyed by a bunch of Wall Street guys doing blow, drinking champagne, and going to really fancy restaurants. It wasn’t really trickling down. Maybe some of the art world was getting some of that money, because these people had money to spend on art; but overall it was a pretty hairy time.”

Opposing Reagan, the Mudd Club staged an ironic inaugural party, Danceteria mocked the bland conservatism of the government’s domestic vision, and venues such as the Loft and the Paradise Garage positioned themselves as safe havens for dancers who lived at the hard-end of economic, sexual, and ethnic discrimination. These and other spots were profoundly aware of the way their practices existed in relation to wider economic and political developments. “The Pyramid was an amalgam of glamour and the grungy surround that we lived in in the East Village,” explains Brian Butterick/Hattie Hathaway, a drag queen who worked and performed at the Pyramid. “We also had a very strong 1960s influence that ran through everything; we were hippyish, if you will, idealistic. But of course we were living in the age of Reagan, so I don’t know how long our idealism lasted. After a couple of years the timbre of the shows became very sarcastic.” Ann Magnuson, who performed regularly at Club 57, Danceteria, and the Pyramid, comments: “At the time, it was, ‘Well, [Reagan’s election] that’s fucked up, but we’re going to keep on doing what we do. People were still saying, ‘I’m not going to let this get me down, or change who I am. But the anger kept on brewing and brewing, and the anger informed everyone’s work and performances. There was a lot more ranting and a lot more screaming and frustration and darker imagery.”

Most pointedly, party hosts and club promoters along with noncommercial creative workers were forced to confront the consequences of Koch’s drive to turn Manhattan into an oasis for property investment. “Between 1982 and 1985, sixty new off ice towers went up south of 96th Street,” write Newfield and Barrett. “Real estate values in gentrifying neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn went soaring, and the exodus of major corporations from New York was stopped. A new convention center was built, a half- dozen luxury-class hotels were financed with tax abatements, and tourism increased, injecting revenue into the Manhattan economy of theaters, hotels, and restaurants” (3–4). Concurrent property price inflation, which rocketed by 125% between 1980 and 1988 in New York City, priced many party hosts and club promoters out of large swaths of Manhattan, while tax abatements that totalled more than $1bn in “corporate welfare” left them full of resentment, as the following examples illustrate.10

Real Estate Determinism, AIDS, and Social Division

The Loft became a site of embattled struggle when David Mancuso left his 99 Prince Street location in June 1984 because his lease was about to expire and the building’s owner wanted to cash in on the rising value of the property market in SoHo. Mancuso could not afford to meet the landlord’s price, and, as a countercultural radical who was deeply committed to running an integrated and ethical party, would not have wanted to anyway, thanks to SoHo’s shift from a zone that encouraged artistic and social experimentation to one that was embedded in boutique consumerism and real estate mania. Mancuso had prepared for his exit by purchasing a building in Alphabet City, which was due to receive a significant government subsidy, but maintains that the move hit problems when the plans to regenerate the neighborhood were abandoned and the crack cocaine epidemic of the mid-1980s began to take hold. Mancuso lost a signif icant proportion of his crowd immediately, with many of his female dancers concerned about venturing into an area where it was so hard to catch a taxi home. Moreover, the very forces that persuaded Mancuso to move encroached on his ability to engage in activism. “It took a couple of years to see what damage Reagan was doing,” recalls the party host. “In 1982 I knew I had to move, and when I moved from Prince Street to Third Street a lot of things changed in my life that meant I couldn’t focus so much on politics. I was just trying to survive.”

Danceteria was also priced out of the real estate market. For three years, the promoters just about met their expenses as they showcased fledging bands, helped pioneer the staging of art-oriented events in a pop setting, and reinvented the interior of the third and fourth floors at a furious rate. But in mid-1985 Alex Di Lorenzo, the property mogul owner of the building, who doubled as part owner of the venture, decided to rent his space out for more money than Rudolf Pieper and manager John Argento could afford. “Our lease was up and the owner of the building had partners who were not part of Danceteria, and were making money from real estate,” recalls Argento. “We rented the whole building for $1.20 per square foot and he [Di Lorenzo] was getting offers of $25 per square foot. His siblings pressed him to rent the building for more money.” A realtor purchased the lease for $600,000, and Pieper and Argento were among the benef iciaries, yet Pieper had no control over the outcome and took little pleasure from the development. “When Danceteria opened, 21st Street was in an abandoned neighborhood,” he recalls. “You could walk for blocks and not f ind anything open at night. Then, gradually, the excitement of New York brought in hordes of moneyed bores from the rest of the country and real estate prices went up. The club would have continued where it was had not some speculator come up with an offer. Now it’s a residential building with ‘apartments of unsurpassed luxury.’ How exciting.”

The Saint closed a little under three years later, apparently due to AIDS, which struck the venue’s membership with particular force because the balcony area doubled as a feverish zone for promiscuous and often unprotected sex; indeed, early on AIDS was nicknamed “Saint’s disease” because the virus was so prevalent among the venue’s members (Shilts 149). Initially, the dance floor dynamic was not affected, largely because the venue’s long waiting list meant that sick and deceased members were replaced seamlessly, and also because the venue offered those who were sick or knew people who were sick with a chance to “dance their troubles away” (as the Saint DJ Robbie Leslie told me). But when turnout began to decline around the middle of the 1980s, Bruce Mailman opened the club to straight dancers on Thursdays and Fridays, and numbers caved in on Sundays as well during the venue’s f inal years.11 “The Fridays stopped and then Sundays became very, very thin towards the end of the 1980s,” comments dance floor regular Jorge La Torre. “I didn’t want to stop going, but when there weren’t enough people to get the party going and f ill the dance floor it wasn’t the same.”

The AIDS epidemic placed signif icant emotional and economic pressure on Mailman, who became involved in a public dispute with Koch as he fought to maintain the right of gay men to regulate their own sexual practices in the Saint and the St. Mark’s Baths (which he also owned). “Because the circumstances have changed, because political opinion makes us bad guys, that doesn’t mean I’m doing something morally incorrect,” Mailman told the New York Times in October 1985 as the tussle unfolded. “In my own terms, my behavior is correct and I’ll do what I believe as long as I can do it” (Jane Gross). However, according to Terry Sherman, a Saint DJ who was close with Mailman, the Saint closed only when a real estate developer made Mailman an eight-f igure offer that would have at least doubled his initial investment, and the owner accepted, in large part to satisfy his investors, who had long expressed their frustration that the immense costs involved in running the club meant they had not seen a return on their outlay. “Bruce was very ambiguous about selling the club because he loved it so much and the last season (1987–88) was actually crowded again on Saturday nights,” says Sherman. “He did say to me, ‘Maybe I shouldn’t sell it this year.’” Although numbers dropped from the mid-1980s onwards, La Torre conf irms that “Saturday nights always had a sizeable crowd,” and the ensuing success of the Sound Factory, which opened in 1989 and attracted a huge white gay male crowd, illustrated that AIDS did not amount to the teleological, retributive conclusion of queer pleasure on the dance floor and beyond. As devastating as the AIDS epidemic was for the Saint community, the venue was sold in the final instance because Mailman also needed to satisfy a set of investors, and those investors wanted to see a return on their money that embroiled the venue in the neoliberal turn.

For its part, the Paradise Garage became entangled in a perfect 1980s storm of gentrification, AIDS, and drug addiction. First the freeholder of the King Street location made it clear to owner Michael Brody that the venue’s ten-year lease would not be renewed when it expired in September 1987—because the empty parking lot that lay next to the Garage was about to be developed into an apartment block, and the new owner of that block along with the neighborhood association insisted that the club close down. “When Michael f irst got the lease there was no one living near the club,” notes David DePino, the alternate DJ at the Garage, and a close conf idant of Levan’s and Brody’s. “On the corner was a parking lot. Eight years later the lot was gone and in its place was a very big and expensive apartment building. The developer and the local neighborhood association wanted the club gone so they persuaded the landlord not to renew the lease.” DePino adds: “Neighborhood associations are powerful. It’s not something a landlord wants to have problems with.” Brody responded by searching out possible new sites, but contracted AIDS soon after and resolved he would not attempt to continue. Brody’s deteriorating relationship with Levan, his totemic DJ, helped him make his decision; always demanding, Levan had become extremely difficult to work with after he became addicted to heroin.

The independent label sector also lost momentum across the mid- 1980s, in part because its representatives were squeezed out by the major labels, which were emboldened by the economic recovery, the commercial success of the CD format, and the marketing bonus provided by MTV. The majors proceeded to cherry pick dance acts such as D Train and France Joli, rip them out of their integrated networks, and mismanage them into producing albums that did not work locally or nationally. Across 1983 and 1984, the majors also started to offer remix commission to cutting edge dance figures such as Arthur Baker, Franc¸ois Kevorkian, and Jellybean, who found themselves working on an increasing number of rock and pop tracks that did not translate in a club context. At the same time, the closing of Danceteria along with the Mudd Club, Tier 3, and other spots that showcased live bands alongside DJs deprived labels such as 99 Records and ZE of their principal means of promotion. Both ground to a halt across 1983–84, and although this could be put down to a mix of exhaustion and misfortune, the mid-1980s did not produce a new wave of danceable punk-funk acts to replace the likes of the Contortions, ESG, Konk, and Liquid Liquid. Nor did a towering f igure emerge to replace Larry Levan when his heroin addiction hardened, or Shep Pettibone after he went on sabbatical in 1984. When Chicago house music started to arrive in the city during 1985, dance DJs embraced it hungrily, in part because by then the majors had succeeded in reclaiming control of dance music, which they flooded with a pop sensibility (Shepherd, 1984a, 1984b).

The mid-1980s New York club-music milieu also fragmented as record companies and club owners attempted to target their offerings with greater precision. Whereas 1970s and early 1980s disco and dance had operated according to the principles of integration and assimilation, mid- 1980s rock and rap shifted away from polymorphous rhythm in favor of a heavier, more aggressive, more masculine aesthetic. The shifting terrain made it difficult for integrationist parties to survive, and Ruza Blue was ousted from the Roxy when the venue’s owner concluded that her vision was not sufficiently prof itable; soon after the venue along with rap music became more tightly def ined and heavily commodif ied as the MC-rapper displaced the DJ-integrator as hip hop’s emblematic f igure. “The management at the Roxy were clueless, and didn’t get what I was trying to do there,” comments Blue. “They started to book a lot of MCs and groups, and the scene became one-dimensional instead of three-dimensional. It became a bit violent and troublesome. There were mostly men in there. Not very exciting.”

Across the same period, the pluralistic sound that could be heard in white gay venues across the 1970s and early 1980s congealed around a beautiful disco/Hi-NRG aesthetic, in part because the high cost of membership and entry to the Saint encouraged its regulars to reimagine themselves as individual consumers rather than participants in a fundamentally collective ritual, which in turn led a significant number to write hostile letters to Mailman when they felt less than overwhelmed at the end of a night. The flurry of letters appears to have contributed to the drug overdose that killed the venue’s most established DJ, Roy Thode, and it also led the sacking of George Cadenas, Wayne Scott, and the venue’s most unlikely DJ, Sharon White, a black lesbian who liked to “play outside the box” (as she puts it). These and other developments encouraged many of those who held onto their positions to eliminate risk from their selections, which in turn led to an aesthetic stasis. The venue’s most popular DJ, Robbie Leslie, acknowledged as much when he told the New York Native in March 1984: “Music has evolved but New York’s gay market has faithfully held on to the romantic period of disco, which was 1978 through 1980. While we’ve all been dancing to that, we haven’t noticed that there are a lot of records being produced that over the past couple of years we’ve ignored because they haven’t f it into the mold that the audience has demanded” (Mario Z). When house music broke into New York in 1985, Saint DJs (with the partial exception of Terry Sherman) rejected it outright. Looking back, Leslie comments: “Overall we were walking on a cliff edge musically at the Saint and product was running scarcer by the week. I felt a feeling of imminent disaster.”

Meanwhile the Garage, the Loft and successor parties continued to espouse a pluralist ethos, but the heightened segmentation of the market, which witnessed rock and rap shift away from dance, and Hi-NRG targeting female pop and gay male dance audiences, left them with little to play beyond house music. Some outfits attempted to blend the sounds of house and rap, but the experiment was short-lived. Politicized by the inherently divisive consequences of neoliberalism and the effects of the crack epidemic on the black community, black rappers, such as Chuck D of Public Enemy, came to see house as “elitist” and objected to the way it tried to “separate itself from the street” (in Chuck D’s words). Back in 1987, the perception that house music’s followers were not interested in addressing the most urgent concerns of the black community led Chuck D to address the issue in more incendiary terms and label the genre as “music for faggots” (Reynolds 49). In so doing, he drew attention to the broader failure of the black community to address the question of homophobia as well as the threat of AIDS, and he also gave expression to the corrosive effects of neoliberalism, which encouraged groups that had once sought out common ground to see each other in terms of opposition and even betrayal.

“In the early ’80s, everything was progressive,” Bambaataa commented in an interview in 1994 (Owen 68). “People listened to funk, soul, reggae, calypso, hip hop all in the same place.” But by the late 1980s, continued Bambaataa, club culture resembled a form of “musical apartheid.” “If you wanted house music, you went to this club, reggae another club, and hip hop yet another club,” he added. In the early 1990s, significant proportion of the “gangsta” rap scene would go on to embrace the Hobbesian trajectory of neoliberalism, or the argument that the world was made up of individuals whose natural mode was one of warlike competition. “Reagan appealed to that American sense of individualism that was really tailor made for the hip hop generation,” comments Mark Riley, a regular at the Loft and the Paradise Garage who worked in the news department of WBLS and LIB. “I am therefore I am; greed is good; the accumulation of wealth is a worthy goal in life; to hell with everyone else.”

The demographic make-up of New York’s clubs shifted in line with the times, with Area a case in point. Opened in the autumn of 1983 by four Californians who wanted to place the idea of art production at the center of their venture, the venue attracted a mix of creative and for the most part hard-up partygoers who were drawn to the ingenious revamping of the club’s interior theme every six weeks. The cost of this work was so expensive the downers are said to have never made a prof it, but a year or so into its existence Area started to attract a new kind of preppy club-goer, and within a couple of years this new type had taken over the space. A dominatrix doorwoman, barwoman, performing artist, and promoter whose boyfriend Johnny Dynell DJed at the club, Chi Chi Valenti notes: “At Danceteria there were one or two of them—they were hideous geeks with a tie. But by the end of Area there were so many of them they weren’t just an irritant, they were a threat, and I took it very personally.” The shift mirrored changes that were taking place in the demographic make-up of downtown, where many low-earning cultural workers were forced to leave due to the cost of rising rents. “When I got to New York [in 1978] my feeling was the most uncool thing you could be was rich,” recalls Ann Magnuson, a performance artist who ran Club 57. “Then what started happening was the most uncool thing you could be was poor, and it sort of switched like that very dramatically. It shifted for me when Reagan got into off ice for the second four years.”

Koch introduced social policies that contributed to the city becoming a more stable and profitable investment prospect while making it much harder for clubs to operate. Falling in line with Reagan’s National Minimum Drinking Age Act, ratified in July 1984, the mayor raised the legal drinking age to 21 in December 1985, ostensibly to prevent college students from drinking and driving. Whatever the intent, the effect on clubs was regressive, because young dancers injected bodies and energy into the culture; interviewed in 1985, Rudolf Pieper referenced the drinking reforms as “the final nail” (Michael Gross). Feeding the panic that surrounded AIDS, Koch also rounded on the city’s gay sex clubs and bathhouses in the name of public health, closing the Mineshaft and the St. Mark’s Baths in rapid succession, even though public health would have been supported much more effectively by backing the numerous organizations—including the St. Mark’s Baths—that were educating vulnerable groups about the disease.

In broad terms, capital fed off club and music culture while offering little in return. When party promoters and musicians sought out cheap spaces in nonresidential areas in order to go about their work in affordable ways, they paved the way for young, smart, cash-poor populations to experience the area, only for that movement to function as the precursor to gentrification. In a parallel development, the government started to highlight New York’s cultural legacy in an attempt to promote the city as a tourist attraction, only for this to lead to the spread of expensive hotels and restaurants that made New York a less livable place for the core populations most likely to contribute to the city’s cultural life. Cultural workers might have contributed to the process of gentrification and tourism, but their involvement was often unwitting given that they were simply seeking out affordable space thanks to their lack of income. Moreover, their presence did not cause gentrif ication to happen, but simply enabled those with more money to move into the area and escalate property prices. Party hosts and club promoters were caught up in the same stream of developments, and their radically reduced presence in downtown New York across the 1980s speaks to the way rising property prices benefited owners and investors at the cost of those who wanted to undertake the simple act of congregating on a dance floor.

Buttressed by the introduction of socially conservative policies around zoning and other policing matters, the further embedment of neoliberal policies supporting the deregulation of the banking sector and property investment across the 1990s and 2000s has reduced the number of places where dancers can head out to such an extent that the regressive period of the late 1980s now resembles a period of wild opportunity. Indeed, the city’s retail, property, and corporate interests have become so embedded that even the dip in the real estate market that followed the banking crisis of late 2008 failed to augur a mini-revival in dance culture. As a result, a generation of teenagers and adults has grown up with few opportunities to dance beyond the comparatively constrained environments of social dance forms such as ballroom and the tango. Within this context, the highlighting of an era when collective, freestyle dance parties were numerous and vibrant reveals not only what New York once was, but also what it can become. The critique of the role played by neoliberal economics and politics in the culture’s collapse brings to the fore the sometimes-obfuscated business and policy agenda that surely must be challenged if an alternative urban environment is to flourish once again.

Notes

1. I am indebted to Jonathan Sterne for suggesting the phrase “real estate

determinism” after hearing an earlier version of this article at the EMP Pop Music

Conference at UCLA on February 26, 2011. My use of the “determinism” moniker

is not intended to suggest that the economic dictates everything around it, including

the cultural, but instead to draw attention to the way the cultural occurs within the

milieu of the economic.

2. Disco historians, such as Alice Echols and Peter Shapiro, refer to 1970s

dance culture as “disco,” but the culture was motored by private parties as well

as public discotheques, from which so-called disco culture got its name in 1973.

Indeed, the private party network was arguably more influential than its public

discotheque counter part for much of the 1970s, which is a case I make in Love

Saves the Day (Lawrence). In addition, the DJs who helped forge disco began their

work in 1970, some three years before the “disco” term was coined, and during

this pre-disco period and after drew on a wide range of danceable sounds that

included but was never reducible to the generic style that came to be known as

disco. Therefore, while “disco” works as a neat description of 1970s dance culture,

it obfuscates its richness.

3. I outline the relationship between the slowdown in the US economy,

the backlash against disco, and the rise of the Republican right in Love Saves the

Day (Lawrence 363–80). An equivalent argument has been made by Peter Shapiro

(227–32) and Alice Echols (205–15).

4. All interviews conducted with the author unless otherwise stated. I am

grateful to John Argento, Ruza Blue, Brian Butterick/Hattie Hathaway, Chuck D,

David DePino, Ivan Ivan, Jorge La Tor re, Robbie Leslie, Ann Magnuson, David

Mancuso, Rudolf Pieper, Mark Riley, Ter ry Sherman, Chi Chi Valenti, and Sharon

White, all of whom I quote in this article. In addition to these interviews, this

article is based on interviewing and archival work (car ried out for a forthcoming

monograph on New York dance culture in the f irst half of the 1980s) that is too

extensive to cite here.

5. By default, they also provided these employees, their friends and their

peers with a premobile phone, preinternet space in which they could congregate,

exchange ideas, and plan projects.

6. Regarding the importance of affect, Laurence Grossberg (253, 268)

maintains that Reagan was able to popularize a new conservatism because he

“embodied the sentiment, passion and ideology of the new conservatism,” and

“placed himself within the popular” both “rhetorically” and “socially.”

7. My emphasis.

8. My emphasis.

9. Indeed even larger numbers did not live in a loft in the f irst place, because

apartments in the downtrodden East Village were considerably cheaper.

10. The inflation figures are sourced from http://www.forecast-chart.com/

estate-real-new-york.html. Accessed Feb. 26, 2011. Soffer (259) provides the tax

abatement details.

11. The introduction of straight nights is noted in “Saint Says ‘No’” 1. In

an interview with Dar rell Yates Rist published in May 1988, Bruce Mailman noted

that Saturdays were attracting something closer to 1,200–500 a week rather than

the regular “3,000 week in, week out,” rising to “6,000” at some special parties

(Yates Rist 18).

Works Cited

Brewster, Bill and Frank Broughton. Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey. London: Headline, 1999.

Buckland, Fiona. Impossible Dance: Club Culture and Queer World-Making. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 2002.

Cheren, Mel. My Life and the Paradise Garage: Keep On Dancin’. New York: 24 Hours for Life, 2000.

Delany, Samuel R. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. New York: New York UP, 1999.

Easlea, Daryl. Everybody Dance: Chic and the Politics of Disco. London: Helter Skelter Publishing, 2004.

Echols, Alice. Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010.

Gross, Jane. “Bathhouses Reflect AIDS Concerns.” New York Times 14 Oct. 1985.

Gross, Michael. “The Party Seems to Be Over for Lower Manhattan Clubs,” New York Times 26 Oct. 1985, 1.

Grossberg, Laurence. We Gotta Get Out of This Place: Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005.

Lawrence, Tim. Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970–79. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2003.

Newf ield, Jack, and Wayne Bar rett. City for Sale: Ed Koch and the Betrayal of New York . New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Owen, Frank. “Back in the Days.” Vibe (Dec. 1994): 66–68. Reynolds, Simon. “Public Enemy.” Melody Maker, 17 Oct. 1987.

Reprinted in Simon Reynolds, Bring the Noise: 20 Years of Writing about Hip Rock and Hip-Hop. London: Faber and Faber, 2007. 47–55. “Saint Says ‘No’ to Straights on Saturdays.” Nightclub Conf idential 1.1 (May 1986): 1.

Shapiro, Peter. Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco. London: Faber and Faber, 2005.

Shepherd, Stephanie. “The 12′′ Single Is Here to Stay.” Dance Music Report (30 Nov. 1984a): 3, 12–13.

Shepherd, Stephanie. “1984: Conservative Consciousness Reigns Supreme.” Dance Music Report (29 Dec. 1984b): 3.

Shilts, Randy. And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. New York: St. Martin’s P, 1987.

Soffer, Jonathan. Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City. New York: Columbia UP, 2010.

Tabb, William K. The Long Default: New York City and the Urban Fiscal Crisis. New York: Monthly Review P, 1981.

Taylor, Marvin J. (ed.). “Playing the Field: The Downtown Scene and Cultural Production, An Introduction.” The Downtown Book: The New York Art Scene 1974–1984. Ed. Marvin J. Taylor. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2006.

Yates Rist, Dar rell. “A Scaffold to the Sky and No Regrets.” New York Native 2 May 1988, 18.

Z, Mario. “Robbie Leslie: The Pat Boone of DJs.” New York Native 12 Mar. 1984, 21 24.

Zukin, Sharon. Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change. London: Radius, 1988.

Dowload this article here (pdf)