‘Disco’ is the overburdened name given to the culture that includes the spaces (discotheques) that were organised around the playback of recorded music by a DJ (disc jockey); the social practice of individual freeform dancing that was established within this context; and the music genre that crystallised within this social setting between 1970 and 1979. Although disco has rarely been taken seriously, its impact was - and remains - far-reaching. In the 1970s, some fifteen thousand discotheques opened in the United States alone, with notable scenes also emerging in Germany, France, Japan and the UK, and the music, which revolved around a four-on-the-floor beat (an even-tempo ‘thud, thud, thud, thud’ on the bass drum), polyrhythmic percussion and clipped vocals, became the best-selling genre on the American Hot 100 during this period.

Since the 1970s, disco, which formally went out of production towards the end of 1979, has moved under a different guise, yet remains prevalent. The clubbing sections of Time Out are testament to the ongoing popularity and vitality of the social practice popularised by disco, and the music’s pounding rhythm is prominent in mainstream pop acts such as Kylie and the Scissor Sisters. Madonna wasn’t just born out of the embers of seventies disco (her debut album was rooted in the New York dance scene of the early 1980s); she also owes her recent revival to disco. ‘Hung Up’, Madonna’s first unblemished success for the best part of a decade, doesn’t just sound like disco (the album from which it is taken, Confessions on A Dance Floor, unambiguously references club culture). In sampling Abba’s ‘Gimme! Gimme! Gimme!’, a staple on the white gay dance floors of 1970s New York, it also recycles disco.

For the most part, disco’s political ambitions have been local. Seventies artists, producers and remixers released records that, inasmuch as they contained lyrics, were focused on the theme of dance floor pragmatics (‘Dance, Dance, Dance’, ‘Work that Body’, ‘You Should Be Dancing’, ‘Disco Stomp’, ‘Let’s Start the Dance’, ‘Turn the Beat Around’, ‘By the Way You Dance’, ‘Dancer’, ‘Can’t Stop Dancing’, ‘Boogie Oogie Oogie’, ‘Fancy Dancer’ and so on). Meanwhile dancers were, and remain, preoccupied with the experience of bodily release, temporary escape and the ephemeral community of the nightclub. Private and evasive, disco and dance successors such as rave have nevertheless been dragged into the centre of mainstream political culture at key moments of ideological struggle. John Major, seeking to establish a post-Thatcherite sense of purpose, picked on dance culture (as well as hunt saboteurs, countryside ramblers and civil liberties campaigners) in his Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994. Mayor Giuliani mobilised his pre-9/11 popular conservative constituency around the clampdown on clubbing activity and the sanitisation of Times Square sex. And the American New Right, searching out a polyvalent symbol of the ‘degenerate’ values of the 1960s (drug consumption, women’s rights, civil liberties, gay liberation, excessive public spending), drew on disco as a key target around which it could mobilise the long-suffering moral majority.

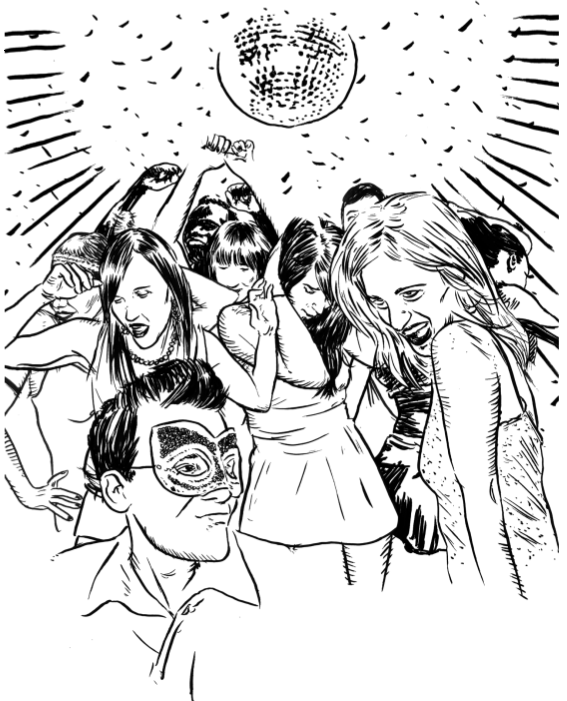

The disco that riled the gathering forces of the New Right was born in cauldron conditions. Lacking alternative social outlets, gay men and women of colour, along with new social movement sympathisers, gathered in abandoned loft spaces (the Loft, the Tenth Floor, Gallery) and off-thebeaten-track discotheques (the Sanctuary, the Continental Baths, Limelight) in zones such as NoHo and Hell’s Kitchen, New York, to develop a uniquely affective community that combined sensation and sociality. Developing a model of diversity and inclusivity, participants established the practice of dancing throughout the night to the disorienting strains of heavily percussive music in the amorphous spaces of the darkened dance floor. While the nonlinguistic practices of these partygoers differed from the direct action of their counterpart street activists, they were similarly committed to the liberation of the dispossessed, and a number of faces could be spotted shuffling between the club and the street. And who was to say that civil rights, gay rights and feminist protestors didn’t experience a form of the transcendence-throughenvelopment that was so central to the dance ritual in the midst of marching, chanting crowds?

The heat and humidity on these dance floors was almost tropical in intensity, and when urbanites and suburbanites picked up on this ethicalkinetic movement (‘Love Train’ by the O’Jays, released in 1972, captured the spirit of the floor and was adopted as a pre-disco anthem) it seemed, at least for a couple of years, as if the transgressive dancers of New York’s ‘downtown party network’ - the network of sonically and socially progressive venues that included the Loft, the Sanctuary, the Limelight, Gallery, the Tenth Floor, Le Jardin, the SoHo Place and Reade Street, which were for the most part clustered in downtown Manhattan - might be about to remould the United States through the sonic and bodily practices of their queer aesthetic. As disco stretched out, however, its DJs became less attuned to the mood on the floor, its clubs more oriented towards looking rather than listening, and its music more geological (structured according to the hardened co-ordinates of the classic pop song in which the lead vocalist and lead guitarist are dominant within a set verse-chorus structure) than aquatic (built around unpredictable structures and fluid non-hierarchical layers of textural sound). The backlash, which began to gather momentum in the mid-seventies, reached its crescendo in the final summer of the 1970s when the rabid rock DJ Steve Dahl detonated forty thousand disco records in a hate fest at Comiskey Park, home of the Chicago White Sox. The Left barely mustered a whisper in disco’s defence. Except, that is, for Richard Dyer.

In its commercialisation disco mirrored the folk and rock movements of the 1960s, and although its marketing, which tracked the upward curve of neo-liberalism, may have been unprecedented within the music sector, disco suffered disproportionately because it had few allies in the major record companies, whose ranks were dominated by white straight executives. Their sympathies lay with the rebellious postures of the Stones and Dylan rather than the gutsy emotional outpourings of the black female divas - among them Gloria Gaynor, Loleatta Holloway, Donna Summer and Grace Jones, as well as the black gay falsetto vocalist Sylvester, author of the gay anthem ‘You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)’ - who established a foothold in the music industry thanks to the consumer support of New York’s heavily gay dance floors.

In retrospect, 1977 was a transitional year. The opening of Studio 54, the glitziest and most exclusionary venue of the disco era, in April, followed by the release of Saturday Night Fever in November, steamrollered the ethical model of the downtown party network into smithereens, at least in terms of the emergent disco industry. Whereas the dance floor was previously experienced as a space of sonic dominance, in which the sound system underpinned a dynamic of integration, experimentation and release, at Studio this became secondary to the theatre of a hierarchical door policy that was organised around exclusion and humiliation, as well as a brightly-lit dance floor that prioritised looking above listening, and separation above submersion. Meanwhile Saturday Night Fever replaced the polymorphous priorities of New York’s progressive venues with the flashing floor lights of 2001 Odyssey and the hyper-heterosexual moves of John Travolta. Whereas the dance floor had previously functioned as an aural space of communal participation and abandon, it was now reconceived as a visually-driven space of straight seduction and couples dancing, in which participants were focused on their own space and, potentially, the celebrity who might be dancing within their vicinity.

Saturday Night Fever and Studio didn’t just dominate the disco landscape of the late 1970s; they also held sway over the cultural landscape of the United States. Fever became the second most popular film of all time (the Godfatherheld onto its poll position) and the best-selling album of all time, while Studio, thanks to its unnervingly compelling combination of celebrity gossip, drug scandal and door-queue carnival, hogged the front pages of the tabloids. As disco exploded in 1978, thousands of discotheque moguls and their patrons mimicked these contorted versions of dance culture, and while the initial experience was thrilling, the effect soon began to fade or, worse still, jar. By 1979 the combination of the shrill white disco pop that had come to dominate the charts and the exclusionary, individualistic practices that had come to dominate the dance floors led disco’s swathe of recent converts to question their new affiliation. Dancing became disengaged, and when a nationwide recession kicked in during the first half of 1979 the groundwork was prepared for the popularisation of the ‘disco sucks’ movement, a network of disco haters that first emerged at the beginning of 1976 and eventually coalesced around Steve Dahl, a disillusioned Chicago-based rock DJ/talk host.

Dahl and his anti-disco followers tapped into the homophobic and racist sentiments that underpinned the rise of the Anglo-American New Right and would culminate in the election of Ronald Regan and Margaret Thatcher. The ‘disco sucks’ slogan evoked the way in which disco drew dancers into its seductive, beguiling rhythms as well as the action favoured by so many of its most dedicated participants, and while Dahl claims to have been more concerned by disco’s superficiality and artificiality than the identity of any of its dancers, these terms had, by the late 1970s, become euphemisms for ‘gay’. As cultural critic Walter Hughes notes, ‘even the subtler critiques of disco implicitly echo homophobic accounts of a simultaneously emerging urban gay male minority: disco is “mindless”, “repetitive”, “synthetic”, “technological”, and “commercial”, just as the men who dance to it with each other are “unnatural”, “trivial”, “decadent”, “artificial”, and “indistinguishable” “clones”’.

Gay men, however, weren’t the sole focus of the anti-disco movement’s rage. Almost as target-friendly were the equality-demanding women and African Americans who had become intertwined with disco and, much to the displeasure of the New Right’s core following, were displacing white straight men from the centre of American popular music culture. ‘I think I tapped into young, brotherly, male - and dragged along for the ride, female - angst,’ Dahl told me. ‘You leave high school and you realise that things are going to be tougher than you thought, and here’s this group of people seemingly making it harder for you to measure up. There was some kind of anger out there and the anti-disco movement seemed to be a good release for that’.

The concerns of the New Right came sharply into focus just as disco’s commercialisation reached saturation point. In 1976, when Jimmy Carter defeated President Ford, nearly seventy percent of voters declared the economy to be their primary concern, yet by 1979 national conditions had dipped dramatically. Meanwhile, the Middle American heartland began to complain ever more bitterly at the way in which sixties social values had become increasingly entrenched in US governmental policy, with Carter perceived to have introduced a series of liberal policies, on issues from abortion to affirmative action, that were deemed to be favourable to African Americans and women rather than the so-called ‘average’ voter. Building on its early formation, when it was known as the ‘middle American’ revolt, the New Right deployed its support for the Protestant work ethos and abstemiousness against the corrupting influences of pleasure and play.

Under Carter, the argument ran, the United States had become unprofitable, valueless, sinful, profligate, stagnant, disorderly, vulgar, inefficient, unscrupulous and lacking in direction. The proponents of this critique might as well have been talking about disco and, to their good fortune, disco - populated as it was by gay men, African Americans and women - contained scapegoats galore. ‘It wasn’t just a dislike of disco that brought everyone together’, Dahl added (before he realised I wasn’t a sympathiser and abruptly ended the phone call). ‘It was all of the shared experiences. But disco was probably a catalyst because it was a common thing to rally against’.

Yet if, for the emergent New Right, disco was a metonym for a degraded capitalism, the organised Left, which had yet to adjust its antennae to the politics of pleasure, wasn’t concerned with that kind of distinction. As far as socialists were concerned, mainstream disco’s flirtation with upward mobility, entrance door elitism and rampant commercialisation was quite enough. Although Saturday Night Fever might have been set in the working class neighbourhood of Brooklyn, disco appeared to be disengaged from the concerns of class inequality, and, in contrast to folk and rock, its vocal content (which was never the point of disco) failed to address the wider social formation. Working one’s body - a common refrain in disco, in which vocal repetition, following in the tradition of gospel, emptied words of their meaning in order to open the self to spiritual inspiration - wasn’t the kind of labour that appealed to the Left in 1979, the seismic year in which Thatcher and Reagan were elected.

It was into this hostile terrain that Richard Dyer seemingly ventured with the publication of his far-sighted article, ‘In Defence of Disco’, which came out in the same month as the Comiskey Park riot. Dyer, however, wasn’t concerned with standing up to the escalating homophobia of the disco sucks bullies because he hadn’t heard their taunts. ‘I was living in Birmingham [in the UK] and was involved in Gay Liberation and I had the feeling that the kind of music that I liked was constantly being disparaged’, Dyer told me.

I was part of the Gay Liberation Front in Birmingham and we put on discos, in the sense that we played music that was on vinyl. They were free or very cheap, and we always befriended people who came along. It was meant to be a whole different way of organising a social space and there was always tension over what music should be played. There were those who thought it should be rock, and those of us who were into Tamla Motown and disco. We were criticised for being too commercial. It was just felt it was commercial, capitalist music of a cheap and glittery kind, rather than something that was real and throbbing and sexual. The article sprang out of the feeling of wanting to defend something when the last thing it needed was defending because it was commercially very successful.

Believing that the left-leaning Gay Liberation Front was out of synch with the wider gay constituency - ‘Most gay men had nothing to do with gay clubs, but gay men who had an identified gay lifestyle were probably into disco and clubbing’ - Dyer decided to pen a response in Gay Left, a bi-annual journal that he worked on alongside a collective of several other men. ‘All my life I’ve liked the wrong music,’ he wrote. ‘I never liked Elvis and rock ‘n’ roll; I always preferred Rosemary Clooney. And since I became a socialist, I’ve often felt virtually terrorised by the prestige of rock and folk on the left. How could I admit to two Petula Clark LPs in the face of miners’ songs from the North East and the Rolling Stones?’

The key problem, according to Dyer, was that disco, in contrast to folk and rock, tended to be equated with capitalism (even though the latter genres had been co-opted by the music industry much earlier than disco). Yet ‘the fact that disco is produced by capitalism does not mean that it is automatically, necessarily, simply supportive of capitalism,’ he countered. Dyer added that whereas rock confined ‘sexuality to the cock’ and was thus ‘indelibly phallo-centric music’, disco ‘restores eroticism to the whole body, and for both sexes, not just confining it to the penis’ thanks to its ‘willingness to play with rhythm’. Anticipating the queer materialist arguments of Judith Butler, Dyer concluded that disco enabled its participants to experience the body as a polymorphous entity that could be remodelled in ways that sidestepped traditional conceptions of masculinity and femininity. ‘Its eroticism allows us to rediscover our bodies as part of this experience of materiality and the possibility of change’.

Dyer was virtually a lone voice however, and while his arguments would have garnered the support of disco’s most dedicated evangelists in the States, this constituency was much too busy with the business of dancing to concern itself with developing (or for that matter reading) a theoretical defence of the genre. That said, Dyer might not have written ‘In Defence of Disco’ had he lived in the unofficial capital of disco - as he did between February and September 1981 - rather than Birmingham. ‘I went to live in New York and when I was there I went to the Paradise Garage,’ he says. ‘I was in a group called Black and White Men Together, I had a relationship with an African American man, and going to the Garage was very much part of that. Obviously there were lots of white people at the Garage, but nonetheless one felt one was going to a black-defined space. That made me reflect much more upon the fact that I was white’. The experience would trigger Dyer’s future work on whiteness, yet had the peculiar effect of closing down his work on disco. ‘I just remember thinking the Garage was fabulous. Of course there was absolutely no one at the Garage or the Black and White Men Together group who spoke about how awful all this disco music was. There was no one who said that. It just wasn’t something that anyone said’. It followed that, in this congenial environment, there was no need to mount a defence.

The tumultuous summer of 1979 bears an uncanny resemblance to the present. As neo-liberals on both sides of the Atlantic aim their fire at the last remaining vestiges of social democracy, people of colour (who ‘drain the welfare coffers dry’ and support ‘gang culture’) and queers (who threaten to undermine the ‘moral fabric of Christianity’) are blamed for the destabilisation of Anglo-American prosperity and order. Meanwhile dance music, which enjoyed a period of prolific creativity during the 1980s and 1990s, when house, techno, drum ‘n’ bass, garage (in its US and UK articulations) and grime made rock look leaden-footed, is once again facing charges of excessive hedonism and aesthetic banality. In Britain, the ebb and flow of the Mercury Prize has functioned as a barometer of dance music’s sliding fortunes. Whereas dance acts such as Reprazent, Talvin Singh and Dizzee Rascal captured the prize either side of the Millennium, rock acts are once again dominant. The winners of the autumn 2005 prize, the queer-torch-singing Antony and the Johnsons, might not fit the pattern of guitar band conservatism, traditional rock acts such as the Kaiser Chiefs and Coldplay filled up the shortlist to such an extent that dance was all but obliterated. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, and seeping back into Britain, came the politicised poetics of … Bob Dylan. Riding on the back of a Martin Scorsese documentary film and an autobiography, the folk-turned-rock star’s latest and most hyped revival has been received by leftist critics as evidence of his timeless political and artistic values, even though Dylan virtually created rock’s centrifugal myth of romantic individualism: the belief that a white straight man, as a creative and authoritative being, can speak for the ‘masses’. When dance plays second fiddle to ageing as well as contemporary rock, it is clear that it has ground to make up.

Yet beneath the narrative of these coincidences and echoes with the late 1970s, the status of disco has shifted considerably and the genre, somewhat surprisingly, has now acquired the aura of an undervalued cultural formation that is rich in musical material and political example. As such it is much easier now than at any point in the last twenty-five years to defend disco, and the reasons for this lie in the effects of AIDS, the death of legendary disco DJs, the commercialisation of rave, a growing interest in the genealogical excavation of the ‘sample’, and the emergence of anti-digital discourses in dance culture.

Fuelled by the rise of Chicago house (a DIY form of post-disco dance music put together with cheap synthesisers and drum machines) and the spread of Ecstasy (the popular feel-good drug of choice that was popularised in the UK during 1988), the rapid expansion of British club culture in the late 1980s was interpreted by dancers, as well as a good number of spinners, as the negation of disco. The pointedly ‘stripped down’ (naked except for the bare bones of percussion and minimalist instrumentation) non-musicality of Acid house, a subgenre of Chicago house, was contrasted with the elaborate productions of the high disco period, and while the early formation of acid and rave culture produced progressive versions of a de-masculinised and deheterosexualised dance floor, discourses around the music were less queer, with house/acid posited as the male straight (stripped down, hard, serious) antithesis to feminised gay disco (elaborate, soft, playful). There was no such disavowal of disco in New York, but nor was the culture valued. The high point of the AIDS epidemic from the late 80s to the early 90s created a milieu for nostalgia, yet the ruling DJ-production forces of the era - Todd Terry (the producer of sample-heavy tracks such as ‘Party People’, ‘Can You Party’ and ‘Bango’) and Junior Vasquez (the DJ at the Sound Factory, who developed a relentless tribalistic aesthetic) - were also moving into the territory of a hard house sound divorced from disco.

The roots of this revival were initially difficult to discern. Following the backlash against disco, the music industry in the States laid off its disco promotion staff - incidentally (but not coincidentally) the first group of openly-gay employees to be employed by corporate America - and replaced the name ‘disco’ with ‘dance’. Disco classics were still much loved, but their heavy rotation by DJs was motivated as much by necessity as desire, the major records companies having reeled in their dance output. Even Chicago house, which broke through towards the end of 1984 and gathered momentum during 1985, became something of an estranged cousin to the 1970s genre. Lazy history has it that ‘house was disco’s revenge’ (the phrase was first uttered by Frankie Knuckles, the DJ at the Warehouse, the key dance venue in Chicago between 1977-83). However, the most influential producers within the nascent genre - Marshall Jefferson and Larry Heard - were more concerned with imagining a contorted, technological future (synthesiser patterns and drum tracks that didn’t imitate disco) than referring back to a wholesome, organic past (synthesiser patterns and drum tracks that did), and the crucible for their experimental tapes wasn’t the Power Plant, where Frankie Knuckles, the mythological ‘Godfather of House’, was spinning a refined selection of disco classics and, when it was sufficiently sophisticated and well-produced, house, but the Music Box, where DJ Ron Hardy, blasted on heroin, was playing anything that sounded strange. The producers of techno, which emerged in Detroit a little after house surfaced in Chicago, were even more decisive than their Windy City counterparts in breaking with disco (even if Donna Summer’s futuristic disco recording, ‘I Feel Love’, was an important inspiration), and when New York started to run full throttle with the house baton in the late 1980s and early 1990s its most influential protagonists were the producer-remixer-DJs Todd Terry and Junior Vasquez, who dipped into disco but were primarily dedicated to developing the merciless sound of hard house - house that was heated in a Petri dish until it was reduced to its disco-inspired, electronically-fortified breaks.

The reverberations of disco were even harder to discern in the British club boom of the late 1980s, which drew heavily on the Chicago subgenre of acid house yet, according to the historians of the rise of house in the UK - Matthew Collin (Altered State) and Sheryl Garratt (Adventures in Wonderland) - was primarily inspired by the holiday island of Ibiza. There, the story goes, a group of white straight lads on holiday (Trevor Fung, Nicky Holloway, Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling, Ian St Paul) sampled the bitter-yet-ultimatelysweet taste of Ecstasy while listening to Balearic music (music popularised on the Island of Ibiza that featured a comparatively slow R&B beat with Latin, African and funk influences, including lots of classical guitar) and house, dancing under the Mediterranean night skies.Within months of their return, Ecstasy-fuelled parties were springing up in London and, to remind them of their Ibizan roots, clubs were regularly decorated with fake palms while employees handed out ice pops and the like. As it happens, house had already taken off in the north, where black dancers - in contrast to their black southern counterparts, who remained committed to the softer humanism of soul - consumed it as a black futurist outgrowth of electro. However this narrative was marginalised by the historians of UK dance, who paid tribute to the black roots of dance in New York and Chicago before attributing the ‘discovery’ of this music not to the Black Atlantic inter-connections forged by black British dancers but by the post-colonial narrative of white British dancers on holiday in the Mediterranean.

At this particular juncture and location, disco wasn’t even pre-history. Acid house’s stripped-down non-musicality provided the ultimate contrast to the elaborate productions that had come to dominate disco, and the UK dance scene simultaneously developed a progressive dance floor politics of sexuality that revolved around de-masculinised and de-heterosexualised identities (amorphous, baggy, intentionally sexless T-shirts were all the rage, while Ecstasy had the partially progressive effect of making straight men want to hug each other rather than chase after women). When the first analysis of this culture was published in a collection of essays edited by Steve Redhead, Rave Off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture, most of the contributors drilled their analysis with Baudrillardian theory and posited the experience as motivated by an aesthetic of disappearance. The fact that the Haçienda, the most popular club in Manchester during the halcyon days of the early house boom, had already been running successfully on an unlikely diet of black electronic music and indie rock prior to the introduction of house was erased by the contributors to Rave Off, as was the direct, New York-based inspiration for the venue, Danceteria, which opened just as disco was mutating into post-disco dance. According to this discourse, the Haçienda didn’t have a history; instead it arrived from a parallel universe (which is probably how most dancers understood their experience).

These years 1987-89 marked a noticeable shift in dance music’s centre of gravity. Whereas New York had been dominant during the 1970s and, in spite of inroads made by Chicago and Detroit, retained its pre-eminent position in the United States during the 1980s, the city’s dance culture was struggling to maintain anything resembling momentum by the end of Reagan’s second term in office. Of course it was AIDS, rather than the histrionic gestures of Steve Dahl, that killed, or at least came close to killing, disco. So rampant was AIDS within the city’s gay clubbing population that the virus was initially dubbed ‘Saint’s disease’, after the Saint, the biggest, most renowned white gay venue of the 1980s, where dancers were dropping in disproportionate numbers. The Paradise Garage, regularly touted as the most influential club of all, was also struck by the virus and closed its doors in the autumn of 1987 when its owner, Michael Brody, fell sick and decided against renewing his ten-year lease. The Saint shut down a short while later in the spring of 1988. ‘One of my best friends was [the owner of the Saint] Bruce Mailman’s assistant, and she said that towards the end the number of letters for membership renewals that were coming back marked ‘addressee unknown’ or ‘addressee deceased’ was just unbelievable’, Robbie Leslie, a resident DJ at the Saint, told me. ‘It wasn’t that the living were cancelling their memberships. It was just that they were dying off and there was nobody to fill the gap. It became an unfeasible operation’.

Ex-gay men, queered through ACT-UP’s trenchant campaign for statesponsored medical treatment and political acceptance, were politicised by the AIDS crisis. As the number of new cases reached its peak in 1993, dancing became less and less of a priority for those who survived. For those who continued to go clubbing, there was no room for nostalgia - the dominant aesthetic of the period was the rough, edgy sound of hard house - so when pioneering DJ Walter Gibbons, the Jimi Hendrix of the disco era who moreor-less invented the modern remix, passed away in 1994 his funeral was unceremonious and attended only by a handful of people. The fate of his record collection, which was donated to a San Francisco AIDS charity only to be returned because they could not be sold, was indicative of disco’s status. Here was a used-up culture for which there was no demand. (Today the collection would attract bids of tens of thousands of pounds, in all likelihood, if it were to be auctioned on eBay.)

Effective HIV therapy was adopted in 1996 and, as it gradually became clear that gay men with AIDS could live with the disease, disco began to come back into soft focus as the ultimate symbol of pre-AIDs abandon, a culture of innocence and release that could never be repeated. Memories and emotions inevitably coalesced around the Saint (especially if you were white and gay) and the Paradise Garage (especially if you were black and gay), and thanks to its greater influence on straight ‘Clubland’ the Garage soon began to bake up the largest slice of the nostalgia cake. The preciousness of the memory of the Garage was heightened further by the death of its resident DJ, Larry Levan, who passed away in 1992. For some, Levan died, at least in spirit, when the Garage (where he had worked as the resident DJ for ten years) closed in 1987. He continued to play at other venues, but the mystique and aura he had nurtured so successfully at the Garage were impossible to sustain, and his extraordinary remixing career ground to a rapid halt. When the spinner was invited to launch the Ministry of Sound, the London venue modelled on the Garage, he showed up empty-handed, having sold his records to feed his heroin addiction. Two years later, significant numbers of diehard New York clubbers turned up to his funeral, and for his next ‘birthday’ ex-Garage heads put on a birthday party, which became an annual event, with each celebration more nostalgic than the last (Garage classics and, in particular, Levan’s productions and remixes, would be played back-to-back at these events). The anniversary parties reached their crescendo when Body & Soul, which opened in 1997 and was quickly honoured as the latest New York party to pick up the torch of the ‘dance underground’, put on a Levan celebration and invited Nicky Siano, a supremely gifted disco DJ and one of Levan’s most influential mentors, to come out of retirement and play. Siano’s performance, true to the spirit of the 1973-77 era, when he played at the Gallery was widely considered to be New York’s most talented and influential DJ, was an extrovert affair and came to symbolise the moment when the latest generation of New York’s downtown clubbers, who had been introduced to the 1980s at previous Levan anniversary parties, began to grasp their culture’s roots in the 1970s and, more specifically, disco.

Plucked out of their cultural and institutional context, which, like any other, was riven with conflict and struggle, disco and Levan became the rose-tinted signifiers of lost communal harmony and musical sophistication. To refer to either one became a way of highlighting a set of aesthetic preferences and paying homage to the past while entering into a coded system that, combining seriousness and cool (two words that were rarely associated with disco during the 1980s), offered the prospect of privileged status to dance aficionados. Around this time it became seemingly obligatory for dance remixers and producers to dedicate their vinyl releases to Levan or the Garage or, more occasionally, the Loft (the influential party organised by David Mancuso from 1970 onwards), and record labels, picking up on the trend, started to release bootleg disco and Garage ‘classics’, largely because demand for these records, for so longer unwanted, was spiralling and fleet-footed Japanese kids, spurred on by Levan’s last ever gig, which took place in Japan in 1992, had been hoovering up the originals with consummate skill.

Unable to fall back on their own history of subterranean party networks and groundbreaking DJ innovators, British club kids were introduced to the sonic if not social possibilities of disco through the dreaded antagonist of the live musician - the sampler. Having come to characterise the cut-andmix aesthetic of 1980s hip hop, the sampler began to influence the shape of house when dance producers and remixers came to understand that their electronically produced tracks could gain a third dimension if they were interspersed with carefully chosen live quotation (a distinctive horn riff, or drum break, or guitar lick, or vocal phrase) from an old disco record. The groundwork for this trend was established by Chicago’s early house producers, who regularly copied (rather than sampled) favourite disco extracts, and this practice was taken to its logical conclusion when Todd Terry, the first major New York house producer and, not by coincidence, a hip hop devotee, placed the postmodern imprint of the sampler at the centre of his house releases during 1987-88. Terry’s technique was well received in New York, but it was the British dance press that, unable to contain its enthusiasm, declared Todd to be God. More or less coinciding with the Japanese hunt for disco rarities, British DJs and remixers, hoping to access disco’s apparently infinite seam of sampling possibilities and having almost invariably missed out on the vinyl first time around, started to do exactly the same.

The trend inspired the musician and writer David Toop to publish a piece on disco and its revival for the Face - the style magazine that had helped break Chicago house in the UK and which was still considered to operate at the cutting edge of British fashion and cool - in 1992. Citing ‘neo-disco tracks’ such as Joey Negro’s ‘Enter Your Fantasy’, Deep Collective’s ‘Disco Elements’, the Disco Universe Orchestra’s ‘Soul On Ice’, Grade Under Pressure’s ‘Make My Day’, the Disco Brothers and Sure Is Pure’s ‘Is This Love Really Real?’ and M People’s Northern Soul, Toop noted the way in which British house tracks were successfully negotiating a ‘space between nostalgia and machine futurism’. In between references to disco’s history of sonic innovation, camp extravagance and commercial saturation, Toop added: ‘Studded with (studied) disco clichés now distant enough to resonate with Antiques Roadshowmystique, throbbing with a new cyber-strength that the old classics could never match, they are smart enough to avoid a headlong plunge into unabashed shallowness’.

The sampler inadvertently introduced unknowing British house heads to the sonic possibilities of disco - however much they were curtailed, these snippets were often the high point of the track - and when streetwise labels started to release compilations featuring the full-length versions of disco tracks that had been popularly sampled, thousands of non-collectors were able to easily access non-commercial disco classics for the first time. These collections demonstrated the consummate skill of the producer/remixer, whose job it was to pick out these fleeting quotations from the complicated, layered text of the disco original. Yet, more often that not, the house track that had rejuvenated the live seventies version suffered in comparison, with the sampled house track sounding shallow and gimmicky when played backto-back against the disco records that had garnished their grooves, largely because the sampler, by highlighting and repeating an unoriginal phrase ad infinitum, can easily become the ultimate producer of cliché.

Even if the house version sounded good in the clubs, where the use of the post-disco technology of the drum machine came into its own via reinforced sound systems (Toop’s point above), the tracks didn’t stand up to - and, importantly, weren’t intended to stand up to - repeated listening. That wasn’t the case with disco, which would regularly employ the finest session musicians of the era in the pursuit of freeform, jam-oriented, transcendental grooves. Disco, so often characterised as worthless ‘cheese’ by UK-based house heads in the late 1980s, started to resemble a fine pecorino, with the full complexity of its flavour only coming to the fore when allowed to mature over time. (House tracks, meanwhile, began to take on the characteristics of a ripe briethanks to their tendency to provide intense pungent bursts of flavour over a relatively short period of time, after which they would start to go sour.)

The backdoor entrance of disco into contemporary house more or less coincided with a structural shift in the organisation of British dance culture. As Collin recounts in Altered State, published in 1997, British dance culture was born in the clubs but started to spread to disused warehouses and hastily erected tents around the M25 when dancers became frustrated with the early closing-time restrictions of Britain’s antiquated licensing laws. The birth of rave at the end of the 1980s ushered in an era of high-tempo techno and progressive house - stripped down, track-oriented music that complemented the spacious, echo-oriented contours of these improvised venues - but the rapid commercialisation of this culture in the early 1990s followed by the passing of the restrictive Criminal Justice and Public Order Act in 1994 dampened the momentum of rave.

That left dancers with a conundrum: having revelled in the initial transgression of Ecstasy culture, after which they rediscovered their enthusiasm through the daring spatial transgression of rave, dancers where beginning to wonder about the true oppositionality of their practices. The almost total failure of ravers to participate in the campaign against the punitive Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which offered an opportunity to join forces with other outlawed groups including ramblers, hunt saboteurs and civil rights organisations, further undermined the sense that dance culture was rebellious as well as hedonistic. With the number of outdoor events in decline, and those that remained tamed by the process of local authority licensing, many dancers returned to the clubs. There they discovered that the multinational drinks companies, whose products had been wholly marginalised by Ecstasy consumption during the late 1980s and early 1990s, were once again calling the shots. Offering clubs lucrative sponsorship deals, alcoholic brands now permeated flyer and related publicity material, and the drinks themselves were repackaged, usually through the deployment of fluorescent colours, in order to appeal to the aesthetic preferences of drug users, who didn’t so much stop taking Ecstasy as combine this consumption with alcoholic intake. As Collin notes, it was around this time that clubbers also started to complain about the quality of the drugs they were taking - an indication that either the active ingredients of Ecstasy were being diluted more and more, or that the effect of the drug was diminishing with repeated use (this being one of Ecstasy’s traits).

Faced with the additional comedown realisation that they were participating in a highly commercial culture in which so-called ‘Superclubs’, which prided themselves on their corporate identities, were coming to dominate the nightscape, a number of dance writers began to seek out an alternative political narrative to contextualise their practice and, looking west rather than south, came up with a new chronology of British dance culture that began not on an Ibiza beach during the 1980s but in NoHo lofts and Hell’s Kitchen discotheques during the 1970s. Collin opened Altered State with a section on the Stonewall rebellion of 1969, the Sanctuary, the Loft and the Paradise Garage, while Garratt devoted the opening chapter of Adventures in Wonderland to the rise of the modern discotheque, culminating in the opening of the Sanctuary, and chapter two to the black gay continuum that began at the Loft and culminated at the Paradise Garage. Sarah Thornton might have commented that the evocation of ‘black gay’ culture served the purpose of endowing the British club and rave narrative with a dose of ‘subcultural capital’ (Bourdieu’s cultural capital within a clubbing context) had she considered disco to be worthy of a single mention in her 1995 book on dance culture, Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital.

The move to highlight the contribution of African American gay men to the culture of disco to the point where, in its earliest formation, disco was black and gay, added an important layer to the historicisation of the genre, even if the black gay element was central rather than dominant at this juncture. Anthony Haden-Guest’s Last Party: Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night, published in 1997 and the first substantial book to be published on disco since Albert Goldman’s Disco (which came out in 1978), had erased this narrative in favour of a scandalous focus on the ultimately marginal celebrity contingent at Studio 54. Yet there was a sense that the switch in popular historiography towards highlighting the black gay presence in early disco culture was motivated less by the desire to produce a history of the marginalised than by the craving for a hip marginality that could lend glamorous credibility to Britain’s increasingly vacuous club culture. The authors of this popular historical narrative of UK dance culture were at the time employed, after all, by trend-setting magazines such as the Face and i-Dthat retained an investment in preserving the fashionable identity of the dance cultures they had helped break, and the black gay component of early New York dance culture seemed to be safe to write about because it was something that had happened in the past - and overseas. If any commitment to a politics of inserting a history of the dispossessed into the history of dance existed, surely they would have also drawn attention to the important incubator role played by early London clubs such as Stallions, Pyramid and Jungle, where black and white gay men constituted the core crowd, and northern venues such as Legend, Wigan Pier, Placemate 7 and the Haçienda, where black (and white) straight dancers embraced the challenging sounds of American dance. That they didn’t do so suggests a willingness to tick the boxes of alternative identity so long as they were positioned at a safe distance. Otherness, in this revised official history of dance, functioned as a prologue to a familiar main narrative: the centrifugal role of the white straight men (who just happened to now be wearing a Hawaiian shirt).

The excavation of disco in the late 1990s was also a sign of the maturation of dance culture - a phase that, for some, represented the scene’s loss of energy, cultural institutionalisation and sedimentation. Just as Britpop had, in the mid-1990s, reminded music consumers of the bleached version of rock history that has the genre beginning with the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, now, for the first time, at least in the UK, dance culture participants were being asked to explore the roots of their own practices. The move was in many respects counter-intuitive. Whereas rock fans tended to follow the career of an artist, collecting their records as, true to the Romantic roots of modern artistry, they developed over time, disco/dance functioned according to the pragmatics of the dance floor. If a piece of music worked, that is, made dancers dance, participants might go out and buy the record; if it didn’t they wouldn’t. However, as the generation of late eighties clubbers grew older, and ostensibly started to spend as much (if not more) time listening to dance music at home as in the clubs, their listening priorities shifted. Record-collecting became more important, especially amongst male consumers, and alongside this process came a new emphasis on the historical genealogy of dance, which invariably led back to disco. Early house heads, who had despised disco when they discovered Chicago house in 1987-88, now began to treat seventies dance as an object for connoisseur-like attention. In addition, as dance consumption shifted from the club to the home, repeated listening became a greater priority and disco, more than house, was able to bear this kind of close sonic scrutiny. The sample might have been a creative tool that could contribute to sonic combinations not available to seventies producers, yet its repetitive and fragmentary logic tended to produce its eventual redundancy. If the sample existed as a superior fragment from a wider text, why settle for just the fragment?

In the second half of the 1990s New York producers, responding to the limitations of the sampler as well as the drying up of the archival well, started to re-emphasise the ‘live’ component of their recordings. Having turned to sampling first time around because they lacked the musical know-how required to produce the sounds that were so abundant in seventies disco, house producers and remixers such as Masters at Work - ‘Little’ Louie Vega and Kenny ‘Dope’ Gonzalez - began to invite session musicians into the studio in order to jam over technologically-generated tracks. In 1997, operating under the Nuyorican Soul moniker, Vegan and Gonzalez took this trend to its logical conclusion and released an entire album, titled Nuyorican Soul, of live recordings that featured legendary seventies performers such as Jocelyn Brown, Vince Montana and Roy Ayers re-recording seventies classics alongside a live band or, in the case of Vince Montana, a whole orchestra. The album sent mild shock waves through Clubland where house fans, raised on a diet of pulsating drum machines, didn’t quite know what to make of the subtler and superficially less dynamic sound of live drums. In terms of its wider politics, the clearest message of the album - that dance music was in danger of eating itself alive if it failed to employ musicians to generate new sounds and reintroduce the ‘feel’ of grooving musicians into the dance matrix - was compromised by the over-emphasis on cover versions of soul classics. The mining of disco and its wider aesthetics, however, was unmistakable and largely welcomed by DJs, dancers and other producers.

The resuscitation of disco in the US and the UK coincided with the wider shift in political culture in which the morally conservative alliances of Reagan/Bush and Thatcher/Major, which propped up their economic liberalism with intermittent bouts of racism and homophobia, gave way to the comparatively progressive social politics of Clinton and Blair. Although there was no let-up in the neo-liberal agenda following the election of the Democratic President and the Labour Prime Minister, the Anglo-American cultural context shifted in important ways, with women, people of colour and gay men/lesbian women co-opted into the newly multicultural, liberal feminist, gay-friendly marketplace. Disco’s revival in the second half of the 1990s can, in this regard, be understood as part of the historical continuum that witnessed the rise of ‘Bling’ - untamed materialism based around the champagne lifestyle of expensive jewellery, fast cars and designer clothes - in US hip hop and UK garage. More amorphous in terms of its black and Latin roots, disco offered a milder entry into the quagmire of racial politics and, following the breakthrough introduction of protease inhibitors and cocktail treatment strategies, which produced dramatic results in the containment of AIDS, it also became a safer and more marketable gay lifestyle product. Disco, having been pronounced ‘dead’ as the New Right swept to power, came back to life (at least in terms of its public profile) as this era came to a close.

Disco’s status as a source of radical musicianship received its ultimate affirmation in the summer of 2005 with the publication of Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco by Wire journalist Peter Shapiro. Notorious for its high-minded avant-gardism, general seriousness and penchant for arrhythmic music, the Wire was never a likely home for complimentary articles about disco. David Toop’s feature on Giorgio Moroder was a rare exception, as were Peter Shapiro’s pieces ‘The Tyranny of the Beat’ and ‘Smiling Faces Sometimes’. As such Shapiro’s book was to be welcomed not so much for its arguments about disco music, which had been set out in other publications, as for the fact that he was taking these arguments, along with a new level of musical detail, to a cynical audience. If only Shapiro’s publishers had understood the wider critical contest that was at stake: their use of sparkling effects and lurid fluorescent colours on the covers of the US and UK editions of the book undermined Shapiro’s attempt to stake out disco’s right to be taken seriously.

The aspect of disco musicality that Shapiro fails to articulate adequately, which also happens to be the aspect that has proved to be the most enduring in terms of aesthetic innovation and global influence, is the role of the DJ. Spinners such as David Mancuso, Francis Grasso, Michael Cappello, Ray Yeates, Bobby Guttadaro, David Rodriguez, Tee Scott, Richie Kaczor, Nicky Siano, Walter Gibbons, Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles developed a mode of communication that mirrored the marathon trance grooves emerging from artists as diverse as Miles Davis, the Grateful Dead and War, although in contrast to the practices of these musicians they functioned as engineers of collage, melding found objects (vinyl records) that originated as distinct entities (works of art) into an improvised aural canvas, and as such challenged traditional notions of musicianship.floor. Experienced producers, vocalists and musicians stood by and gasped as weedy, know-nothing DJs were let loose in the studio and slashed their carefully constructed recordings, highlighting some tracks and cutting out others. The resulting releases, which revolved around an aesthetic of stripped down beats, the groove of the rhythm section and clipped vocals, set out the blueprint for house - the genre that would later return to these records for sample-friendly material.

One of the attractions of the seventies dance environment was the streetlevel status of its DJs, who were for the most part anonymous, low-paid music enthusiasts. In their hunger to search out new sounds and put on parties for friends, they became conduits for a new genre of music, but in spite of the often-adoring reception they would receive from the floor, only the most deluded could have imagined that they were a star or celebrity outside of their cocooned mini-universe. DJs were lucky to get an occasional mention in the media. Nicky Siano was probably the best-known spinner of the decade, yet his cuttings library consisted of a three-paragraph mini-feature in New York magazine and a couple of quotes in articles about disco that ran in the nationals. Some, such as Mancuso, and to a certain extent Levan, were media shy and believed that a higher media profile might undermine the feverishly protected privacy of their parties at the Loft and the Paradise Garage. But this fails to explain how the Paradise Garage, during a ten year reign at the apex of Nightworld that spanned the seventies and the eighties, didn’t receive a single feature exploring its dynamic - and only a short obituary in Billboard when the venue finally closed. Larry Levan and owner Michael Brody might not have favoured press coverage, but the press also wasn’t especially interested in a micro-scene whose black gay core continued to exist outside of the public eye.

Today, following the repeated excavation (and defence) of disco, a Google search on the Paradise Garage or Levan will yield results of some 135,000. Even Mancuso, perhaps the most influential pioneer of seventies disco, yet a barely-known figure outside of the downtown party network until Nuphonic Records released a compilation of Loft classics in 1999, achieves about 52,000 results. Fascination and the desire to experience in some respects go hand in hand, and many attribute the resurgent popularity of figures such as Mancuso to a wider desire to taste a slice of seventies disco. Of course the clock cannot be turned back to the 1970s, but the persistence of seventies and classics nights - adorned with, in the worst-case scenario, an industrial quantity of glitter, neon, wall mirrors and Bee Gees/Village People pop - indicates that promoters and, presumably, dancers are not about to tire from trying. To dance to disco at one of these events is not akin to experiencing the 1970s, for seventies music, played in the seventies, would have sounded new and challenging, while today it will normally sound like music that is thirty years old (whatever the symbolic or affective significance of that might be).

Some, such as Energy Flash author Simon Reynolds, argue that disco is a reactionary force in contemporary club culture. Writing for the Village Voice in July 2001, Reynolds is gently critical of New York’s ‘double take’ around disco, whereby a number of clubs - most notably Body & Soul - are seen to be evoking dance music’s ‘roots, origins, and all things ‘old school … With clubbing tourists coming from all over the world to experience ‘the real thing’ as a sort of time-travel simulacrum, New York’s ‘70s-style dance underground has become a veritable heritage industry similar to jazz in New Orleans’. Reynolds, however, overstates his case. Even the Levan birthday parties can’t be equated with disco nostalgia nights - the Levan remixes that form the staple of these nights were for the most part recorded in the post-disco era of the 1980s, and the classics (tried and tested favourites from the seventies and eighties) normally give way to newer music that references the past while teasing out the future - and nobody in New York has produced what might be called a disco record since the very early 1980s. While Todd Terry initiated the trend of sampling disco in New York, his biggest audience was in the UK, and it was in the UK that the practice was deployed to the point of saturation. New York producers and remixers responded to this particular malaise by combining live instrumentation with technologically generated beats - a step ‘backwards’ that is implicitly criticised by Reynolds (‘New York dance culture hasn’t delivered the shock-of-the-new in well over a decade’), but which has been a regular tool of the progressive music makers that Reynolds lauds elsewhere (such as jungle producers digging through their old record boxes in order to redeploy the bass from Jamaican dub into breakbeat techno).

Reynolds’s real problem with New York’s ‘disco-house tradition’ would appear to be ‘the scene’s premium on old-fashioned notions of ‘musicality’ and ‘soulfulness’’, which runs in opposition to his preference, outlined in Energy Flash, for dance music that is part of a rave/hardcore continuum built around ‘noise, aggression, riffs, juvenile dementia, hysteria’. Yet while the producers of hardcore have contributed to the creation of a dance market in which subgenres develop and disappear with startling speed, the mutant disco producers of the so-called deep house scene are engaged in a project that, evoking Amiri Baraka’s concept of the ‘changing same’, is more concerned with continuity and longevity than disruption and transience. Political struggle can only be ongoing if affiliations, rather than being dropped as soon as a more futuristic option emerges, are maintained over time.

(When the two paths converge - around, say, drum ‘n’ bass, which added jazz riffs and dreamy synthesizers to jungle’s throbbing rudeness - Reynolds tends to disapprove. Nevertheless such a strategy, which finds contemporary expression in the Deep Space dub-meets-techno-meets-disco framework developed by François Kevorkian, as well as Maurizio’s techno-oriented dub productions for Rhythm & Sound, offers a potentially productive solution to the conservatism and radicalism that runs through much of dance culture. For now, demand is strong enough to sustain all three approaches.)

Veteran seventies DJs who are still playing today - including the highprofile David Mancuso, Nicky Siano, François Kevorkian, Danny Krivit and Frankie Knuckles - are to varying degrees expected to deliver a seventies agenda (even if the agenda in the seventies was to play new music, not seventies music). The arguments that flow across discussion boards such as Deep House Page (www.deephousepage.com) and DJ History (www.djhistory.com) after a Mancuso Loft party, for example, illustrate the conflict that inevitably surrounds the performance of a ‘legend’ outside of her or his original milieu. Disco nostalgists (both those who experienced the seventies first time around, and those who weren’t there but wish they had been) are critical of Mancuso’s non-disco selections, of which there are a good number, while others urge the one-time cutting edge pioneer to play a higher proportion of new records in order to demonstrate the template’s relevance to the current conjuncture.

Whether it is through the playing of a disco record, the snatching of a disco sample or the mutation of disco’s sonic imprint, disco’s reach might be shrouded yet it is also resilient and widespread. Just as significant, though, is disco’s social template. First outlined by Richard Dyer back in 1979, and developed by Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson (Discographies: Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound) and Maria Pini (Club Cultures and Female Subjectivity) some twenty years later, disco’s politics of pleasure, experimentation and social equality, which draws on the potentially queer/affective experience of the amorphous body moving solo-with-the-crowd to polyrhythmic music, remains an enticing objective every time a DJ comes into contact with a group of dancers. Disco, like any music genre, is vulnerable to commercial exploitation. Yet few music genres (it is hard to think of any) have been so successful at generating and spawning a model of potentially radical sociality.

Thanks to Jeremy Gilbert for comments on an earlier draft of this article

To download this article click here.