How might we analyse the relationship between sexuality and the dance floor in 1970s disco culture- a culture that is commonly ridiculed, yet which was often progressive and continues to inform the contemporary thanks to its innovations within DJing, remixing, social dance and sound system practices? It has become commonplace to read disco as the site where a binary contest between gay and straight was staged: that disco emerged as an outgrowth of the Stonewall Rebellion of June 1969 and unfolded as a predominantly male gay subculture; that the dance movement was subsequently co-opted, commodified and tamed by films such as Saturday Night Fever (1977), which established it as a safe haven for straight courtship; and that the commercial overkill that followed the runaway success of the RSO movie culminated in an overtly homophobic backlash that turned on the culture’s perceived latent gayness. Rather than repeat this narrative, however, I want to outline some of the ways in which dominant conceptions of sexuality cannot fully account for the phenomenon of disco, and will argue that the conditions that coalesced to create the 1970s dance floor revealed disco’s queer potential- or its potential to enable an affective and social experience of the body that exceeded normative conceptions of straight and gay sexuality. In the analysis that follows, I will be referring to practices that unfolded in the United States, and in particular, downtown New York, where disco’s queerness was arguably most marked, even though the culture’s scope was ultimately international.

In order to assess the significance of queer disco, it is necessary to note that the social dances that preceded disco- most notably the Waltz, the Foxtrot, the Lindy Hop (or Jitterbug), the Texas Tommy and the Twist- were to varying degrees patriarchal and heterosexist. If this claim is sweeping, truncated and in some respects crude, it nevertheless draws attention to theway participants could only take to the floor if accompanied by a partner of the opposite sex, as well as the reality that in this situation it remained standardpractice for men to assume the lead. That did not make the dancesirredeemably regressive. To being with, they were often no more gendered than the wider social settings within which they emerged, and social dancebecame a site where these norms were challenged as well as imposed. As dance historians such as Katrina Hazzard-Gordon (1990) and Marshall and Jean Stearns (1994) note, vernacular dance provided African American communities with a reason to congregate as well as a channel for expressive release,while the under-historicized culture of drag balls that dates back to the Harlem Renaissance disrupted gender signifiers and roles. Successively, these dances also allowed for an increasing amount of space to exist between the dancing couple, and in turn this provided the female follower with greater independence from her male lead.

Yet on the eve of 1970, prior to the breakthrough of the social dance formation that would come to be known as disco, the rising autonomy of the female dancer in dances such as the Twist continued to be tempered by the ongoing role of men as the gatekeepers of the dancer floor. And while gay men were ushered to the front of the door queue in venues such as Arthur (a comparatively liberal discotheque situated in midtown Manhattan) on the basis that they would help energize the dance floor, once inside they could only take to the floor within the structure of the ostensibly heterosexual couple, andthe same restrictions were applied to lesbian women. Arthur closed in June 1969 not because the Stonewall rebellion made its practices look archaic, but because the pre-disco discotheque craze of the 1960s had come to resemble atired fad. At this particular historical juncture, dance floor practices lagged behind the demands of feminist and queer activists.

Instead of fading out altogether, however, social dance assumed a new form at the beginning of 1970 with the more or less simultaneous emergenceof two influential venues. In one, David Mancuso staged the first in a longseries of private parties that came to be known as the Loft in his NoHo apartment on Valentine’s Day. In the other, two gay entrepreneurs known as Seymour and Shelley, who were influential players in the gay bar scene in Greenwich Village, took over a faltering straight venue called the Sanctuary that was located in the run-down Hell’s Kitchen neighbourhood of midtown Manhattan. Together these venues contributed to the forging of a relationship between the DJ (or ‘musical host', as Mancuso prefers it) and the dancingcrowd that continues to inform the core practice of contemporary danceculture. And although gay men were an important majority presence in both of the Loft and the Sanctuary, participants (including participants who self-identified as gay men) did not consider either venue to be gay.

The Loft brought together several diffuse elements: the rent party tradition that dated back to 1920s Harlem; the practice of loft living in downtown New York, which emerged in the late 1950s and 1960s as manufacturers began toleave the city; the rise of audiophile sound technologies, which followed the introduction of stereo in the late 1950s; Timothy Leary’s experimental LSD parties; and the gay liberation, civil rights, feminist and anti-war movementsthat Mancuso aligned himself with during the second half of the 1960s. Mancuso, who had grown up in an orphanage in upstate New York, was used to experiencing families as unstable and extended, and brought this outlook into his parties, which attracted a notable proportion of black gay men, as well as straight and lesbian women. ‘There was no one checking your sexuality or racial identity at the door,’ says Mancuso. ‘I just knew different people.’ Because the Loft was run as a private party, Mancuso could have run it as anexclusively male gay event, but he chose not to. ‘It wasn’t a black party or a gay party,’ he adds.‘ There’d be a mixture of people. Divine used to go. Now how do you categorise her?

’The Sanctuary was also indelibly heterogeneous.‘ It had an incredible mixture of people,’ recalls Jorge La Torre, a gay male dancer.‘ There were people dressed in furs and diamonds, and there were the funkiest kids from the East Village. A lot of straight people thought that it was the coolest place in town and there were definitely a lot of women because that was part of what was going on at the time’ (because gay men such as La Torre were often involved sexually with straight women).‘ I would say that women made up twenty-five percent of the crowd from the very beginning, probably more. People came from all cultural backgrounds, from all walks of life, and it was the mixture of people that made the place happen.’ It would have been difficult for Seymour and Shelley to turn the Sanctuary into an exclusively gay discotheque, even if the idea had occurred to them. First, New York State law continued to assert that male- male dancing was illegal and discotheques were accordingly required to contain at least one woman for every three men; the female quota was filled by lesbians as well as straight women who wanted to be able to dance without being hit on by straight men. Second, while the Sanctuary’s owners could have paid off the police in order to get around that obstacle, it is unlikely there would have been a thousand self-identifying gay male dancers to fill up the venue in this formative stage of queer dance culture. Finally, straight dancers wanted to be part of the nascent disco scene, and thanks to the venue’s public status, which meant that anyone who joined the queue could potentially get in, there was no obvious way to identify and exclude them.

I am not simply questioning the common assumption that early discoculture was homogeneous in terms of its male gay constituency just because this is manifestly inaccurate and contributes to the systematic erasure of other histories, including the history of lesbian women. I also want to argue that the reductionist focus on disco’s male gay constituency underestimates and even undermines the political thrust of early seventies dance culture, which attempted to create a democratic, cross-cultural community that was open-ended in its formation. Dance crowds were aware of their hybrid character as well as their proximity to the rainbow coalition of the counter cultural movements of the late 1960s, and having witnessed the repressive state reaction against Black Panther activists, Stonewall Inn drag queens, and Kent State University and Jackson State University anti-war demonstrators, they took to exploring the social and cultural possibilities of the counter cultural movement in the relatively safe space of dance venues. In these settings, dancers engaged in a cultural practice that did not affirm their maleness or their femaleness, or their queer or straight predilections, or their black, Latin, Asian or white identifications, but instead positioned them as agents who could participate in a destabilizing or queer ritual that recast the experience of the body through a series of affective vectors.

Social dance

Whereas dancers in the 1960s took to the floor within the regulated structure of the heterosexual couple, dancers in the 1970s began to take to the floor without a partner. The transformation underpinned the historical experienceof gay male sexuality: the longstanding practice of cruising encouraged gay men to be open to the idea of moving onto the dance floor autonomously, while ongoing legal restrictions around male- male dancing encouraged gay male dancers to continue to take to floor and dance as singles- at least until the law that restricted men from dancing with each other was repealed in New York in December 1971. At the same time, however, the shift to solo dancing was partially inaugurated within the culture of the 1960s music festival, where women and men started to dance in a swaying motion to the sound of acid rock. Because of this, straight Sanctuary dancers who had participated in events such as Woodstock would have already been habituated to the idea of dancing solo, while others might have encountered the discourse of liberation that was so pervasive during this period else where. As George Clinton sang in 1970, ‘Free your mind and your ass will follow.’ On the floor, dancers did not experience the displacement of couples dancing as an individualistic and isolationist prelude to the neo-liberal era, in which the principles of partnership and cooperation would be savaged, but instead as a new form of collective sociality that exceeded the potentially claustrophobic contours of the previous regime.

Aside from that regime’s promotion of compulsory heterosexuality, the social dynamic of partnered dancing was necessarily limited because the men and women who formed dancing couples had to concentrate on their partnerin order to move rhythmically and expressively- and also avoid physical injury. As a result, dancing couples were internally focused, and communication with other dancers, never mind the musicians or the DJ, was a secondary matter. In contrast, the dancers who participated in the private party and public discotheque network of the early 1970s were able to develop free form movements, and because of this they experienced an increased ability to communicate and dance with multiple partners. As Frankie Knuckles, a male gay regular at the Loft, notes of that setting: ‘You could be on the dance floor and the most beautiful woman that you had ever seen in your life would come and dance right on top of you. Then the minute you turned around a man that looked just as good would do the same thing. Or you would be sandwiched between the two of them, or between two women, or between two men, and you would feel completely comfortable.

’The experience described by Knuckles does not merely describe the displacement of one sexual objective (to dance in order to seduce a member of the opposite sex) with another (to dance in order to seduce several members of both sexes). Bisexual promiscuity might be queerer than monogamous heterosexuality, but to entertain such a framing would be to entirely misread the function of the dance floor exchange by reducing it to intercourse. Instead dancers regarded the exchange as their primary objective, not as a means to an alternative end, and in contrast to the framing of earlier social dance forms, which were intended to service compulsory heterosexuality, the emergent dance milieu of the early 1970s articulated no equivalent function. While all manner of sexual liaisons could be read into the free flow of movement on the floor, with the opportunity for gay men to meet other gay men in a novel setting the most marked, participants, including male gay participants, have insisted that any intercourse that could come about at the end of the night was only exceptionally more than a secondary concern. This continued to be the case even at venues such as the Saint, the white gay private party that opened on the site of the old Filmore East in 1980, where sex could be enjoyed in the balcony area, but remained a side attraction for most.

By turning on a single spot, then, dancers could move in relation to a series of other bodies in a near-simultaneous flow and as part of an amorphous and fluid entity that evokes Deleuze and Guattari’s Body without Organs(BwO). Described by Ronald Bogue (2004, p. 115) as ‘a decent red body thathas ceased to function as a coherently regulated organism, one that is sensed as an ecstatic, catatonic, a-personal zero-degree of intensity that is in no way negative but has a positive existence, ’the dance floor BwO contrasted with other crowd formations: the cinematic crowd because it was physically active rather than passive and in constant communication rather than silent; the sports stadium crowd because its attention was not directed to an exterior event; the marathon runner crowd because its pleasure was based not on remaining within the crowd but rather leaving it behind; and so on. In other words, the very being of the dance floor crowd revolved around its status as a collective intensity, and while its resonance with the often asexual Deleuzian concept of the BwO could lead some to question its queerness, its erotics of bodily pleasure- an erotics that intersected with gay liberation, the feminist movement, and the counter-cultural revolt against 1950s conformism- confirms its disruptive sexual intent.

The DJ

The second factor to consider with regard to the queering of the dance floor is the DJ, whose craft was transformed by the shifting social contours of the dance floor. Earlier DJs saw themselves as subservient waiters who served up music prepared elsewhere, or as puppeteers who could manipulate the dancers. Whatever their sense of self-worth, DJs were also charged with the responsibility of encouraging dancers to not only dance but also leave the floor and visit the bar, because that was how most venue owners made their money. But as the Sanctuary DJ Francis Grasso confided, the newfound collective force of the 1970s dance crowd meant he had to change his style. Grasso is interesting because he was the only employee to survive Seymour and Shelley’s buyout of the Sanctuary, which means he witnessed the difference between playing to the regulated straight crowd and the more open, heterogeneous crowd that entered the venue at the beginning of 1970. ‘When the Sanctuary went gay I didn’t play that many slow records [records introduced to work the bar] because they were drinkers and they knew how to party,’ says Grasso. ‘Just the sheer heat and numbers made them drink. The energy level was phenomenal. At one point I used to feel that if I brought the tempo down they would boo me because they were having so much fun.

’Of course dancers did not just communicate by booing the DJ. They would also clap and cheer and whistle, while the very energy of their movements was also communicative, and it became the primary role of Grasso and his contemporaries to read the mood of the crowd and select a record that was appropriate for the moment. Because they were now attempting to both lead and respond, DJs contributed to a form of anti phonic music making that has characterized a great deal of African American music, and in order to increase the effectiveness of their playing in relation to the crowd, DJs started to segue and then beat-mix between records in order to maintain the rhythmic flow, or purchase two copies of the same record in order to extend the parts that their dancers particularly liked. As a result, a form of illegitimate music making emerged in which the conventional performing artist was displaced by the improvising figure of the DJ, who could draw on a wide repertoire of sounds and programme them within a democratic economy of desire. Thanks to the absence of the performing artist and the relative anonymity of the DJ, dancers began to respond to the sonic affect of the music rather than the image of the performing artist, and this unconventional circuit subtly challenged the hierarchical underpinnings of the music industry, in which the vocalist, musician and producer held an elevated position above the listener. Because the disembodied recording artist could be heard but not seen, the dancer could also begin to think of her or himself as a contributor to the collectively generated musical assemblage, and could also respond to the music outside of the hierarchical relations of artistry and fandom.

Dance music

Third, I would like to consider the position of pre-recorded music in this moment of flux and change. Again, the contrast with the 1960s is instructive, because whereas discotheque DJs of that era tended to play from a limited rockand roll repertoire that encouraged a similarly limited style of dance, and festivals/concerts from the same period tended to foreground the singular sound of rock, discotheque DJs of the early 1970s drew from a broad range of sounds. The term ‘disco music’ did not emerge until 1973, and when it did it referred not to a coherent and recognizable generic sound, but instead to the far-reaching selection of R&B, soul, funk, gospel, salsa, and danceable rock plus African and European imports that could be heard in Manhattan’s discotheques. Even when the sound of disco became more obviously recognizable during 1974 and 1975, DJs would intersperse the emergent genre with contrasting sounds. The introduction of sonic contrast and difference helped generate a sense of unpredictability and expectation on the dance floor, and the juxtaposition of different styles enabled dancers to experience existence as complex and open rather than singular and closed. In other words, DJs were generating a soundtrack that encouraged dancers to be multiple, fluid and queer.

At the same time, the disco genre, which drew together elements that could be found in R&B, soul, funk, gospel and so on, also generated a queer aesthetic, even in its singular incarnation, and this was something that was highlighted by Richard Dyer (1979/1995) in his article ‘In Defence of Disco’. Dyer, who completed his PhD at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in Birmingham, might have been isolated in his interest in gay sexuality, and perhaps even his love of disco, in that setting; these elements of popular culture received scant attention from other Cultural Studies scholars whose focus was directed towards class relations, the mods and the punks, government policy and, when Angela McRobbie (1980) raised her voice, gender. Dyer initially set out to defend disco from the leftist attack that, in contrast to folk as well as elements of rock, it amounted to little more than some kind of commercial sell-out, and his argument turned out to be apremonitory critique of the left’s reluctance to engage with the politics of pleasure. Yet it was Dyer's analysis of the aesthetic properties of disco music and the relationship of these properties to the body and conceptions of sexuality that is of greater concern here.

In the article, Dyer outlined a number of the key distinctions that existed between rock and disco. Whereas rock confined ‘sexuality to the cock’ and was thus ‘indelibly phallo-centric music’, disco, argued Dyer, ‘restores eroticism to the whole body’ thanks to its ‘willingness to play with rhythm’, and it does this ‘for both sexes’ (1979/1995, p. 523). Disco also offered dancers the chance to experience the body as a polymorphous entity that could be re-engineered in terms that confounded conservative models of masculinity and femininity, for as Dyer added: ‘Its eroticism allows us to rediscover our bodies as part of this experience of materiality and the possibility of change’ (1979/1995, p. 527). In other words, disco opened up the possibility of experiencing pleasure through a form of non-penetrative sensation- and he made this case shortly before Michel Foucault, following a trip to the United States, called for the making ‘of one’s body a place for the production of extraordinary polymorphic pleasures, while simultaneously detaching it from a valorization of the genitalia and particularly of the male genitalia’ (Miller 1993,p. 269). Published in Gay Left, the bi-annual journal of a collective of gay mento which Dyer belonged, ‘In Defence of Disco’ did not prompt a wider discussion about queer sexuality within the Cultural Studies discourse of the time, but three decades later that anomaly has been corrected.

The preference of the early 1970s dance floor for polymorphous ratherthan phallic rhythms is illustrated by the contrast between Olatunji’s ‘Drums of Passion’ and Santana’s cover of the same track, which was re-titled ‘Jingo’. Whereas Santana’s rock version developed a rigid beat and foregrounded the phallo-centric instrumentation of the electric guitar and the male voice, Olatunji’s original recording emphasized rhythmic interplay along with a chorus of voices that developed a call-and-response interchange between themselves and also the drummers. The owner of both recordings, Grasso only played the Santana version when he DJed in front of the pre-Seymour and Shelley straight crowd at the Sanctuary, but when the crowd diversified at the beginning of 1970 he immediately realized he could start to play the Olatunji. As Grasso recounts: ‘I said to myself, '‘If Santana works then the real shit is going to kill them!’’ I was good at mixing one record into another so I played the Santana and brought in ‘‘Jin-Go-Lo-Ba’’. The crowd preferred the Olatunji, where there’s no screaming guitar. They got into it straight away.’

Queerness could be harder to detect in the lyrics themselves, in large part because they drew so heavily on R&B’s heavily heterosexual thematics. Yet thanks to the support of a gay male constituency that was affluent enough to spend a significant amount of money on music, the black female diva became a key figure within disco, and vocalists such as Gloria Gaynor and Loleatta Holloway would go on to express their surprise that gay men should be their most fervent followers. Wronged by her man, Gloria Gaynor exemplified the way African American divas could be both emotionally articulate and grittily resistant when she recorded ‘I Will Survive’, which was released as a B-side until DJs and dancers homed in on the recording and prompted the record company to re-release the song as an A-side. In this instance, queerness had more to do with surviving heterosexuality than subverting it.

Other tracks developed lyrics that were deliberately innocuous because their clipped, repetitive content was designed to accentuate the beat and persuade the dancer to focus on affective sound rather than discursive meaning, while a third group of unknowingly queer recordings laid down heterosexual themes that turned out to be ripe for appropriation- so ‘Free Man' by the South Shore Commission acquired a new layer of meaning when gay male dancers interpreted it as an anthem of gay liberation rather than a tussle between two straight lovers. Then again, sometimes the straight trajectory of a lyric did not have to be reinterpreted if the delivery was strong enough in the first place, and that turned out to be the case in elements of Loleatta Holloway’s rendition of ‘Hit and Run’. In his remix of the record, Walter Gibbons took out Holloway’s first rendition of a frankly embarrassing set of lines that included references to the vocalist being an ‘old fashioned country girl’ who would ‘know what to do’ when ‘it comes to loving you’. But when the vocalist returned to the theme in an improvised vamp that had been largely cut from the original release, the delivery was so remarkably forceful their lame meaning was rendered totally irrelevant.

Temporalities and technologies

Temporal strategies also contributed to the emergence of non-dominant experiences of the body in the dance environment of the 1970s. The practice of staging parties late at night became the founding premise of a culture that aimed to invert the priorities of a society organized around day time work, and the protection afforded by darkness as well as the protected space of the danceparty enabled disenfranchized citizens a level of expressiveness they rarely enjoyed during the day (something Judith Halberstam [2005] has commented on in her book In A Queer Times and Place). In addition, the forward march of teleological time- the time of bourgeois domesticity and capitalist productivity- was upset within the disco setting, where repetitive and cyclical beat cycles created an alternative experience of temporality and the absence of clocks enabled dancers to move into a realm in which work- the work of the dance- was not required to be productive in a conventional economic or indeed heterosexual sense. Within this setting, DJs drew on a range of records that cut across temporal and spatial boundaries in order to evoke and in some respects create a radically diverse sonic utopia. Their practice of using two copies of a record to not only collapse but also extend time- by, say, extending a particularly popular section- culminated in the creation of a new disco format (the twelve-inch single) that enabled DJs to play long mixes that were specially remixed for the dance floor.

The emphasis on temporal length was important. If the record was long, the dancer had a greater opportunity to lose her or himself in the music, and therefore to enter into an alternative dimension that did not so much evacuate the site of the body as realign it within a new sonic reality. The new sonic reality turned out to be especially forceful in private party spaces (such as the pioneering Loft) that did not sell alcohol and could accordingly stay open long after the public discotheques that were governed by New York’s cabaret licensing laws had to close. The extended hours encouraged partygoers toengage in marathon-style dance sessions in which the physical was prioritized over the rational, and this opened up participants to the experience of the body as an entity that was not bounded and distinctive, but rather permeable and connected.

The confined space of the dance floor, in which dancers would inevitably come into contact with one another, heightened the experience of the body as extended and open, and a range of sound system, drug and lighting technologies enhanced this further. Julian Henriques (2003) has described the Jamaican sound system as a form of ‘sonic dominance’, in which the sonic takes over from the visual and creates a community based on sound. In these situations, the sound permeates the body, and therefore creates a situation in which the bounded body (often characterized as the masculine body) is penetrated and becomes difficult to maintain as a separate and unified entity.This was precisely the kind of situation that was engineered in disco, where figures such as David Mancuso as well as engineers such as Richard Long and Alex Rosner introduced a range of technological innovations in order to produce both purer and more powerful sound. Drugs- in particular LSD- were consumed in order to further the dancer’s distance from the everyday and enable entry into an alternative experience of both time and space, as well as to encourage the body to form a connected alliance with sound. Meanwhile, lighting was deployed sparingly, because bodies were more likely to exceed everyday constrictions in an environment that emphasized the connective dimension of the aural above the separating dimension of the scopic (because sound enters the body more forcefully than light). In as much as lighting was used, it was usually aimed at creating disorienting effects, again in order to encourage the dancer to experience the dance floor as an alternative and experimental space.

The conjunctural moment of the early 1970s encouraged these elements and practices to be adopted by a significant range of dancers and venues. This, after all, was the period when the counter-cultural movement's discourse of change, liberation and internationalism continued to resonate; a range of newly-politicized yet disenfranchized groups doubled their efforts to seek out liberated spaces; state repression of political activists encouraged a migration from the dangerous site of the street to the protected haven of the club; the failure of the first wave of discotheque culture and simultaneous evacuation of downtown New York by light industry opened up a plethora of unused spaces that were perfect for dancing; and the music industry had yet to work out how it was going to respond following the failed political promises of rock culture. Along with the Loft and the Sanctuary, spaces such as the Haven, the Limelight, Salvation, Tambourine and Tamburlaine operated dance floors that were remarkably coherent in terms of their social and aesthetic practices. For a while, protagonists believed that they were forging a culture that would go onto reshape the world and in some respects their aspirations have been borne out, if only because so many of their then nascent practices continue to echo. Yet the queer potential of the early 1970s dance floor also proved to be vulnerable to various forms of dilution and co-option, and this process unfolded in three notable ways.

First, a range of party organizers and accomplice dancers sought to split up the early disco scene into a series of discreet groups that were organized around identity, and this led to an inevitable closing down of the demographic range on New York’s dance floors as well as the emergence of a more normative and static conception of what kind of identities could be articulatedin the dance setting. De facto white-only male gay venues such as the Tenth Floor and Flamingo, which deployed Mancuso’s private party template to consolidate a self-anointed ‘A-list’ crowd, could be seen as examples of this kind of practice. Of course these venues catered to a demand because a significant fraction of white gay men considered themselves to be part of some kind of elite that was organized around beauty, professional success and intelligence, and only wanted to dance with men they judged to be their equals. What is more, participants in this stratum of New York dance culture regularly perceived their actions to be politically radical, because gay culture was still historically marginal and the practices of disco were understood to be aesthetically progressive. The tribal experience remained powerful and stoodas a challenge to many conservative practices. But it did not include people who were not white and male, and therefore revealed the way in which dance venues that were organized around gay men could enact an otherwise regressive social agenda. Largely excluded from these venues, lesbian women opened their first dedicated discotheque, the Sahara, in 1976; the four lesbian women who ran the business made a point of introducing a weekly slot when men could participate.

Second, as the demographic constituency of disco was divided and subdivided, a number of promoters began to seek out what they perceived to be an elite dance crowd, and this resulted in the introduction of a marked hierarchy with the dance scene from 1977 onwards, when a series of huge midtown mega-discotheques opened on the premise that they would cater to an elite audience that was organized around fashion, film and so on. The most famous of these was Studio 54, which bore some unlikely links to the culture of the Loft, but ultimately instituted a competitive and hierarchical entrance policy. Huge crowds would form outside the venue every night, and while the owners declared their intention to create a democratic mix inside, the prevailing culture was one of cruel exclusion. It followed that a venue that was so self-absorbed with its status would pay more attention to the scopic than the aural to lighting rather than sound, to being seen as a form of validation, and to the possible presence of a celebrity and so the primary activity at Studio was not dancing but looking. For reasons already outlined, this undermined the venues potential to function as a space of queer becoming.

Third, in order to sell disco to the perceived mass market- the suburban market, or the Middle American market- entrepreneurs reframed disco as the popular site for patriarchal masculinity and heterosexual courtship. The most notable example of this involved the filming of Saturday Night Fever, which was released at the end of 1977. Organized around the culture of the suburban discotheque and the figure of Tony Manero, played by John Travolta, the filmenacted the reappropriation of the dance floor by straight male culture in as much as it became a space for straight men to display their prowess and hunt for a partner of the opposite sex. The film also popularized the hustle (a Latin social dance) within disco culture, and in so doing reinstituted the straight dancing couple at the centre of the dance exchange. In an equally regressive move, the soundtrack was dominated by the Bee Gees, which threatened to leave viewers with the impression that disco amounted a new incarnation of shrill white pop. None of this would have mattered if the film had sunk without a trace, but it went on to break box office and album sale records, and in so doing established an easily reproducible template for disco that was thoroughly de-queered in its outlook.

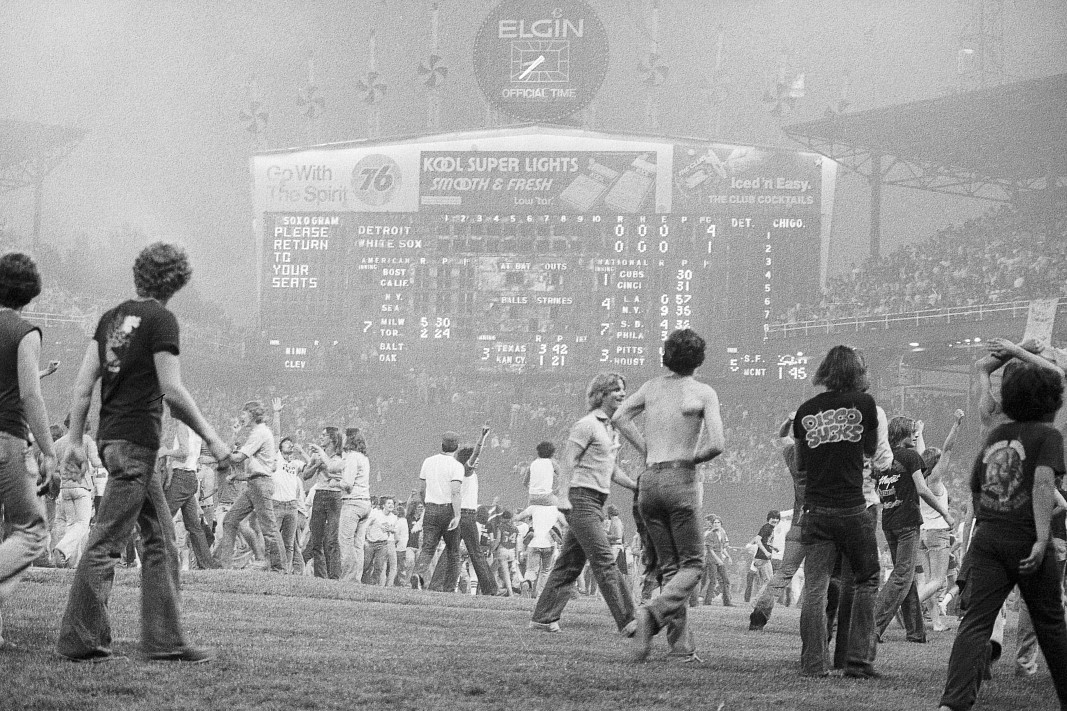

By 1979 conditions were ripe for a backlash against disco. Following the unexpected commercial success of Saturday Night Fever, major record companies had started to invest heavily in a sound that their white straight executive class did not care for, and when the overproduction of disco coincided with a deep recession, the homophobic (and also in many respects sexist and racist) ‘disco sucks’ campaign culminated with a record burning rally that was staged at the home of the Chicago White Sox in July 1979. The coalition of disenfranchized citizens that lay at the heart of disco culture were identified as the beneficiaries of 1960s liberalism, which in turn was blamed for the economic failure of the 1970s. As Stuart Hall (1989) and others have argued, this turn to a conservative discourse complemented and in many respects underpinned the accelerating shift to the individualistic, market-driven priorities of what was then referred to as the New Right, and which is now more commonly described as neo-liberalism.

Yet the backlash did not mark an end to disco per se, because the Loft and its multiple off shoots, including the legendary Paradise Garage, which was modelled on Mancuso’s party, continued to organize their dance floors according to the communal and explorative principles set out at the beginning of the 1970s. Indeed Richard Dyer ended up travelling to live in New York between February and September 1981, and having danced at the Paradise Garage, started to develop the philosophical framework that culminated in the publication of White (1997). In effect, the perceived failure of disco was really therefore the failure of a form of disco that valorized the patriarchal, the heterosexual and the bourgeois, and not the queer disco that I have outlined in this article. As such, the failure was not so much a failure of queerness as a failure of the regressive attempts to contain queerness and appropriate disco. This failure of the dominant rather than the queer would become more explicit in the period that ensued the backlash against disco, when non-hegemonic forms of dance culture flourished. That they, too, failed to become hegemonicis another story altogether.

Download the pdf .