During the 1970s and early 1980s, a diverse group of artists, musicians, sculptors, video filmmakers and writers congregated in downtown New York and forged a radical creative network. Distinguished by its level of interactivity, the network discarded established practices in order to generate new, often-interdisciplinary forms of art that melded aesthetics and community. “All these artists were living and working in an urban geographical space that was not more than twenty-by-twenty square blocks,” notes Marvin J. Taylor, editor of The Downtown Book. “Rarely has there been such a condensed and diverse group of artists in one place at one time, all sharing many of the same assumptions about how to make new art.” The musical component of this network was prolific. Minimalist and post-minimalist “new music,” disco, new wave and no wave emerged in downtown Manhattan during the late 1960s and 1970s; free jazz continued its radical flight during the same period; and hip hop mutated into electro in the early 1980s. During this period of frantic productivity, musicians attempted to work across the sonic and social boundaries of their respective genre-led scenes, while venue directors sought to introduce innovative musical programs that were performed against a shifting visual backdrop of installations, specially-commissioned artwork, lighting effects and experimental video films. It was, in short, a remarkable period in the history of orchestral and popular music in terms of aesthetic innovation and social relations as well as the way in which creativity and sociality are bound together. Arthur Russell, I argue in this essay, was not only a representative product of the downtown music scene, but also that his interactions with a range of musicians, scenes, spaces and technologies marked out the network’s radical potential.

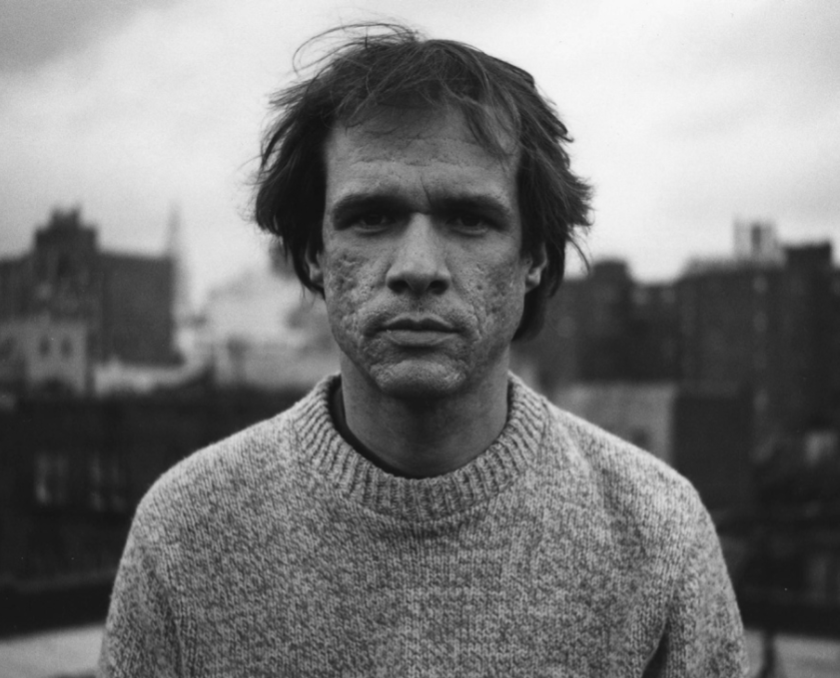

Following his arrival in New York in the summer of 1973, Russell performed and recorded orchestral music, folk, new wave, pop, disco and post-disco dance, as well as a distinctive form of voice-cello dub. If such a broad-ranging engagement was implicitly rhizomatic ⎯ or structurally similar to a horizontal, non-hierarchical root network that has the potential to connect outwards at any point, and is accordingly heterogeneous, multiple, complex and resilient ⎯ Russell intensified the non-hierarchical, networked character of his practice by working within these genres simultaneously rather than moving from one to another according to a sequential, dialectical logic. In addition, he also attempted to establish meeting points between downtown’s diverse music scenes, not in order to collapse their differences and generate a single sound, but instead to explore the points of connection that could provide new sonic combinations and social relationships. Although Russell worked beyond sound when he linked up with choreographers, photographers and theatre directors, his main focus was on the music he produced with a mutating group of musicians, many of whom were sympathetic to his cross-generic project. Russell regularly emphasized the presence of this collective network above his own input when it came to choosing artist names for his records, and he also developed a range of sounds that articulated and reinforced the decentralized complexity of the downtown scene. For these and other reasons, I will argue that Russell’s work can be best understood through the development of a new concept: the concept of rhizomatic musicianship, or a musicianship that moves repeatedly towards making lateral, non-hierarchical sounds and connections.

In developing an analysis of a musician who worked across generic boundaries in relation to a specific space and time, I hope to theorize the way in which a progressive musicianship can be understood in the context of the writings of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari ⎯ who developed the materialist metaphor of the rhizome in A Thousand Plateaus ⎯ as well as Manuel DeLanda’s elaboration of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the assemblage. Studies of music that begin with this theoretical framework have focused on composers who have developed their oeuvre within a single genre, or on specific genres that encourage rhizomatic practices or rhizomatic sounds (such as jazz fusion, dance and dub). However, very little has been written that begins with the musician, which implies somewhat problematically that composition and genre are the primary structures through which musicianship always takes place. Given that the concepts, practices and effects of composition and genre have contributed significantly to the stratification and hierarchical division of music, an analysis that starts with the musician offers an alternative way of analyzing sound according to its immanent rhizomatic potential (because sound, as I will go on to argue, can only move according to rhizomatic movements). Of course this focus runs the risk of framing the artist in the same terms that eulogize the composer as an individualized genius. To focus on Russell, though, is to focus on a collaboratively minded, commercially unsuccessful practitioner who wanted to make music that could build communities and touch the cosmic.

In order to avoid privileging Russell as an isolated genius, or conversely as a mere product of a determining social system, I develop an analysis of the downtown assemblage ⎯ a body of interacting buildings, creative producers, technologies and other components ⎯ that draws attention to the territory’s decentered, rhizomatic character. Second, I set out the terms of what might be called a “rhizomatic politics” and point to some of the ways in which Russell’s music is rhizomatic, providing an overview of his work in three aesthetic blocks ⎯ orchestral/compositional music, pop/rock music and disco/dance music. Third, I discuss Deleuze and Guattari’s writings on music, as well as the way in which their thoughts have been applied to a range of musical genres. Fourth, I expand my concept of rhizomatic musicianship through a detailed analysis of Russell, drawing out his relationship to genre (the organized spectrum of sound), making music (practices through which sound is generated), audiences (the intended recipients of sound), becoming-woman/child/animal (the non-dominant groups with whom he identified) and the cosmos. Finally, I introduce some concluding thoughts about the strategic consequences of Arthur Russell’s rhizomatic politics. Of course Russell did not read Deleuze and Guattari, or sit down in order to map out a strategy that could be characterized as rhizomatic, yet it is through A Thousand Plateaus that the contours and relevance of Russell’s musicianship can begin to be theorized.

1. The Downtown Assemblage

In A New Philosophy of Society, Manuel DeLanda draws on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of the assemblage to suggest that all social entities ⎯ from the subpersonal to the international ⎯ can be best understood through an analysis of their components. These components are not defined by their role in a larger assemblage, so “a component part of an assemblage may be detached from it and plugged into a different assemblage in which its interactions are different.” And although components have a degree of autonomy, the properties of the component parts do not explain the assemblage as a whole because the whole is not an “aggregation of the components’ own properties but of the actual exercise of their capacities.” In other words, assemblages are not reducible to their parts but emerge out of the interactions between their parts, so the capacities of a component “do depend on a component’s properties but cannot be reduced to them since they involve reference to the properties of other interacting entities.” Assemblage theory offers an alternative method for analyzing the world because components are not merely products of a grander social macro-structure. At the same time, DeLanda’s conclusion that an assemblage amounts to “more than the sum of its parts” avoids the pitfalls of an individualist perspective that interprets society as a “mere aggregate.” The collaborations and the network are more important than any purportedly individual contribution, even if the creative producers in the network are active agents and not mere products.

Assemblage theory enables an analysis of downtown New York that refuses to fetishize the territory’s industrial buildings as autonomous monuments of a bygone era, and the theory also helps avoid a portrayal of downtown’s artistic population as constituting a series of discreet creators whose individual contributions resulted in the “aggregate” of downtown. At the same time, assemblage theory encourages a critique that interprets downtown New York as being more than the “mere product” of a shifting historical era that marked the demise of industrial capitalism and the onset of neoliberal capitalism in the West. Born in Mexico in 1952, DeLanda moved to New York City in 1975 and made a number of short films on Super 8 and 16 before he became a programmer and computer artist in the early 1980s. Maybe his experience convinced him he was neither nothing nor everything.

A swirl of labyrinthine streets that offset the geometric grid of midtown and uptown, the SoHo/NoHo/TriBeCa assemblage of downtown Manhattan functioned as the center for the city’s light industry until structural limitations persuaded manufacturers to relocate to cheaper and more accessible zones during the 1960s. In search of expansive living spaces that were sufficiently cheap to enable them to pursue an unprofitable line of work, a range of artists, musicians, photographers, sculptors, video filmmakers and writers moved into the deserted area of downtown and forged a radical artistic community. Meanwhile, as downtown broke with its manufacturing past, industrial technologies were replaced by a series of creative technologies that ranged from traditional art materials and musical instruments to cutting-edge video cameras and synthesizers. These three sets of components ⎯ the space of downtown, the cultural producers who moved into the area, and the technologies they deployed ⎯ combined to generate a diverse range of concerts, exhibitions, installations, video films, sculptures and dance parties, as well as multi-media works and events that combined more than one of these elements. At times it was difficult to see a pattern in these forms of expression, although a general link could be detected in their attempt to break with the perceived straightjacket of the past (uptown) and the commercial (midtown) in order to develop an experimental minimalist and post-minimalist alternative.

There was no privileged player in the reconstituted milieu of downtown New York. While it is tempting to attribute absolute agency to the artists who moved into the empty loft spaces and proceeded to produce a radical art, they were only able to move into the neighborhood because, light industry having moved out, the state decided to sanction their illegal occupation of the abandoned buildings as a cost-effective way to regenerate the area. In addition, downtown’s semi-derelict condition and geographical location encouraged artists to develop an alternative practice that distanced them from the more comfortable conditions and rituals of midtown and uptown art, while the expansive contours of the lofts inspired them to develop big, bold, energized works ⎯ works they might not have produced in another milieu. The materials and technologies they used to make their art also acquired a level of agency, with the found objects of the neighborhood suggesting new forms of collage or installation, or new technologies such as the computer, the synthesizer and the video camera offering novel ways to capture the world. Most importantly, the sheer openness of downtown en-couraged a wide-range of creative producers to move into the geographical zone, and the resulting concentration of artists helped generate meetings and collaborations that would not have happened if these sets of creative practitioners had remained geographically discreet. With no clear hierarchy in the relationship between people, buildings and machines, downtown amounted to a collective aggregation of components that could act both materially and expressively, as well as either increase (territorialize) or decrease (deterritorialize) its degree of homo-geneity. Like all assemblages, the network did not evolve outside of the interactions of its components, and to varying degrees these interactions had material effects on the development of the network.

Although downtown did not follow a linear path of either deterritorialization or territorialization during the 1970s and 1980s, an overarching trajectory can be traced. The downtown assemblage deterritorialized from the manufacturing assemblage when light industry and its attendant workforce moved out. Cheap rents enabled the artistic population to survive by combining their work with part-time jobs ⎯ even Philip Glass had to return to taxi driving following the premiere of his acclaimed score for Robert Wilson’s opera, Einstein On the Beach ⎯ while nascent performance spaces received some support from public funding bodies. Downtown practitioners also produced a deterritorialized art by avoiding the methods that were being sponsored by established institutions (most notably in uptown Manhattan) or commercial entertainment institutions (which were located in midtown Manhattan), and the broad-ranging make-up of the downtown “artists’ colony” resulted in interdisciplinary meetings and collaborations that deterritorialized their former dis-ciplines. The hybrid, fragmented and fractured aesthetic that came to dominate many of these productions helped reinforce the downtown assemblage’s decentered character. “[T]he vernacular of Downtown was a disjunctive language of profound ambivalence, broken narratives, subversive signs, ironic inversions, proliferate amusements, criminal interventions, material surrogates, improvised impersonations, and immersive experientiality,” notes the art critic Carlo McCormick. “It was the argot of the streets, suffused with the strategies of late-modernist art, inflected by the vestigial ethnicities of two centuries of immigration, cross-referenced across the region-alisms of geographic and generational subculture, and built from the detritus of history on the skids as a kind of cut-up of endless quotation marks.”

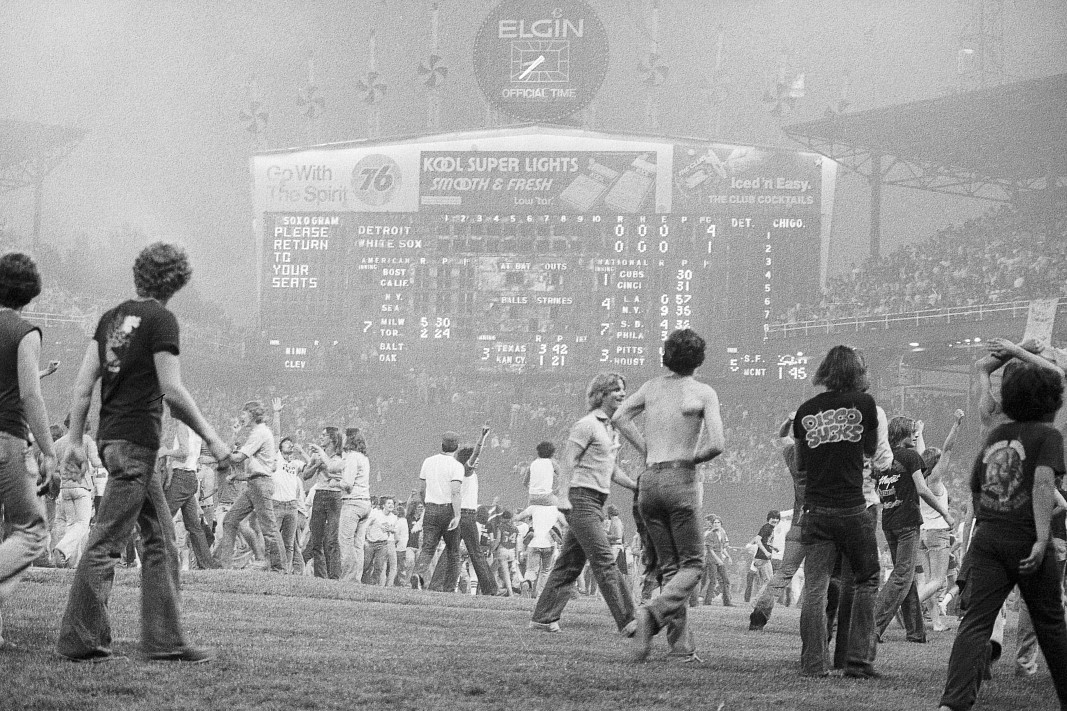

Three types of musician converged in downtown Manhattan during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Compositional minimalists started to perform in a range of spaces, including the Kitchen, an experimental venue for video and music that was located in the Mercer Street Arts Center; rock minimalists began to play in adjacent spaces in the Mercer Arts Center, with the New York Dolls taking up a residency in the venue’s Oscar Wilde Room from June to October 1972; and David Mancuso (the Loft), Robin Lord/Nicky Siano (the Gallery) and Richard Long/Mike Stone (the SoHo Place) staged all-night parties in a cluster of loft spaces. Although the collapse of the building that housed the Mercer Street Arts Centre in the summer of 1973 upset the equilibrium of these music scenes, each reacted by establishing a firmer and more demarcated foundation in downtown, with the Kitchen, the Loft and the Gallery moving to larger, more centrally-located premises, while the displaced rock minimalists regrouped in an underused, unpopular venue called CBGB’s, which was situated on the Bowery. By the time the reconfiguration was complete, each music scene was committed to a form of experimentalism yet operated as one of a series of self-contained aesthetic and social entities.

If the music scene was in a state of limited flux, with musicians exploring boundaries within but not between generic parameters, many still perceived music to be a space of relative mobility, in part because the art scene had been commodified more rapidly. The first art gallery opened in SoHo in 1968 ⎯ perhaps because art objects such as paintings were cheaper to create than musical recordings, and art was more attractive than music to individual investors ⎯ and journalistic accounts of “the rise of SoHo” focused on the area’s burgeoning art market. This process of commodification encour-aged individual artists to develop an identifiable and marketable style, and this relative sedimentation (or “molarization” in Deleuze and Guattari’s terms) of the art market prompted a number of artists to explore the freer (or more “molecular”) music scene. Laurie Anderson, a sculptor, followed this path by combining spoken word poetry with processed violin playing, and when the Rhode Island School of Design graduates David Byrne, Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz arrived in the city they quickly switched their attentions to the less institutionalized music scene. “When I came to New York I guess I was very na�ve,” Byrne told a reporter from Art News. “I expected the art world to be very pure and noble. I was repulsed by what I saw people putting themselves through, the hustling to try and get anywhere. My natural reaction was to move into a world that had no pretense of nobility. Since I’d always fooled around with a guitar, I formed a rock band.” One can imagine Deleuze and Guattari approving of their decision. “In no way do we believe in a fine-arts system; we believe in very diverse problems whose solutions are found in heterogeneous arts,” they write. “To us, Art is a false concept, a solely nominal concept; this does not, however, preclude the possibility of a simultaneous usage of the various arts within a determinable multiplicity.”

Cultural practitioners started to work in earnest across generic and disciplinary boundaries from the mid-seventies onwards. If they had not done so already, galleries, concert spaces and dance venues refashioned themselves as multi-media environments that promoted a range of artistic practices, many of which were presented against the backdrop of a sound system and a DJ. Showcasing a wide range of downtown performers, these venues began to attract significant audiences, which in turn meant that the performers could expect to be paid for their efforts. More than ever before, downtown artists and musicians could look forward to earning a modest income from their art, and this encouraged a further surge in productivity that culminated in what McCormick describes as “a total blur.” Downtown’s rhizomatic assemblage became a multitude, which made it ⎯ drawing on Tiziana Terranova’s description of multitudes ⎯ difficult to control yet also enormously productive thanks to its “dynamic capacity to support ‘engaging events,’ while acting with a high degree of distributed ‘autonomy and creativity’.”

The artistic movement was territorialized in legal terms in June 1974 when the New York authorities passed the Emergency Tenant Protection Act, which validated the previously shady practice of loft living and specified that residents had to be artists (or manufacturers). However, the attempt to revitalize downtown as a dedicated artistic zone in which residents would maintain the local infrastructure and start to pay taxes proved to be unsustainable. Realizing that prices could not be held down indefinitely and that the state would not be able to restrict residential use, a number of artists bought up properties as a real state investment, and at the same time non-artists also started to move into the area ⎯ either because they liked it or because they recognized an excellent investment opportunity when they saw one ⎯ and took to arguing with the regulatory authorities that they were in fact artists. During the second half of the 1970s, the gentrification of SoHo accelerated, with the opening of the Dean and DeLuca supermarket in 1977 a potent symbol that the area was no longer run “by the artists, for the artists,” even if the artist presence was still central to the area’s “cool” cachet.

Even when it was cheap, SoHo was still too expensive for many creative practitioners, and so many ended up living in satellite neighborhoods such as the East Village and Alphabet City. This process accelerated after property prices skyrocketed at the end of the decade, and towards the beginning of the early 1980s the New York Rocker declared that because “‘old SoHo’” had become an “affluent Disneyland” of “chi-chi novelty shops… and chi-chi eateries,” downtown now extended from “from Alphabet City to the Fulton Fish Market, NoHo to Tribeca [sic.].” The expansion of downtown resulted in the closing down of the supposedly Utopian period when artists were able to live only with other artists, although it could be asked: what is so Utopian about artists being able to live with each other? In the expanded version of downtown ⎯ a downtown that no longer revolved around SoHo ⎯ artists stopped thinking of neighborhoods such as the East Village as secondary satellites, and they also began to value the way in which they shared their buildings and streets with a variety of non-artists.

This expanded version of creative downtown also came under attack during the first half of the 1980s. The Reagan administration’s decision to divert money from welfare and the arts to the military resulted in arts organizations having to become financially self-sufficient, which in turn encouraged them to take fewer risks when drawing up cultural programs, and downtown’s identity as an area for artistic experimentation was further undermined when the beneficiaries of the stock market boom started to move into its chi- chi lofts. Taylor dates the end of the downtown era at 1984, by which time “the larger art world had encroached on the scene.” Kyle Gann, who writes about downtown music for the Village Voice, agrees that some kind of decisive shift had taken place. “After 1985, commercial pressures were about as difficult to avoid in Downtown Manhattan as rhinoceroses,” he comments. The pressures on downtown’s alternative culture continued to intensify during the 1990s when the AIDS crisis hit its peak and Mayor Giuliani set about clamping down on New York’s nightclubs and “cleaning up” the city.

Then again, the obstacles and limits did not always come from outside. “To read the history of Downtown between the decades, or what really happened between 1974 and 1984, is not to follow the footsteps imprinted in history but the skid marks of spontaneous encounters and urgent negotiations,” writes McCormick in The Downtown Book, and this kind of depiction of downtown is becoming commonplace. Yet McCormick introduces a point of qualification when he adds that the “dichotomy between external disillusion and insider membership is a relationship Downtown struck not only against the mainstream but also consistently upon itself” and that almost every “congregation that mattered was invented on its own conditions and fabricated its own turf.” The music scenes that emerged around new music, new wave/no wave and disco/dance were as notable for their internal rules as their laid back openness, and it was left to figures such as Arthur Russell to demonstrate that these sonic blocks of experimentation ⎯ the blocks of compositional music, pop and new wave music, and dance music ⎯ were porous.

Having lived in Oskaloosa, Iowa, between 1951 and 1967, and then San Francisco between 1968 and 1973, Russell moved to New York in the autumn of 1973. He spent his first months living uptown, near to the Manhattan School of Music (MSM), where he was studying, but headed downtown when Allen Ginsberg (a friend from San Francisco) invited him to share his East Village apartment. A westernized Buddhist who pursued his spiritual practice most intensely between 1970 and 1973, Russell thought about returning to San Francisco, where he could spend time with Yuko Nonomura, his spiritual teacher, and go hiking in the mountains. Yet Russell moved from Oskaloosa to San Francisco to New York because he judged these assemblages to be progressively less hierarchical and more intertwined, and although downtown Manhattan consisted of series of scenes that “fabricated” their “own turf,” they also proved to be relatively permeable. It was in downtown New York that Russell’s interactions proved to be most productive ⎯ i.e. where he was most effected and effective ⎯ and his interactions with other musicians formed part of the material exchange that led to the downtown assemblage becoming more eclectic, democratic and hybrid. Russell appears to have understood that he worked not as an autonomous individual but instead in relation to other creative practitioners given that his work emphasized repeatedly the process of interaction rather than his own authorship, and it was in downtown that he was most able to work rhizomatically between genres or scenes.

2. Rhizomatic Politics and Arthur Russell’s Musical Work

What might it mean to work rhizomatically? The key principles can be drawn from A Thousand Plateaus, a decentered, non-sequential book in which Deleuze and Guattari foreground their sympathies in the introductory chapter, which is titled “Introduction: Rhizome.” “A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines,” write the authors. “You can never get rid of ants because they form an animal rhizome that can rebound time and again after most of it has been destroyed.” Extending the category of the rhizome to include other natural and non-natural networks that are similarly organized, the authors add, “[T]he fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction ‘and… and… and…’” The rhizome is therefore indicative of Deleuze and Guattari’s realist ontology in that it is material (because strawberry plants, the internet, swarms of bees and other rhizomatic phenomena exist in the world) and metaphysical (in that it raises abstract questions about the nature of being), and it also contains an immanent spiritual goodness. “We’re tired of trees,” they write. “We should stop believing in trees, roots, and radicles. They’ve made us suffer too much. All of arborescent culture is founded on them, from biology to linguistics. Nothing is beautiful or loving or political aside from underground stems and aerial roots, adventitious growths and rhizomes.” Avoiding dualistic distinctions, Deleuze and Guattari caution that elements of the rhizome and the arborescent can be found in each other, and comment that there are “despotic formations of immanence and channelization specific to rhizomes, just as there are anarchic deformations in the transcendent system of trees, aerial roots, and subterranean stems.” But these nuances are submerged when they conclude: “Make rhizomes, not roots, never plant! Don’t sow, grow offshoots! Don’t be one or multiple, be multiplicities!”

How can a “beautiful/loving” rhizome be distinguished from a “despotic” rhizome? Or, what differentiates a progressive rhizome from a regressive rhizome? In the absence of any clear lead from Deleuze and Guattari, I would like to suggest that non-despotic rhizomes display an ability to co-exist with other rhizomes, or be faithful to the principles of their own structure, whereas despotic rhizomes are characterized by an inability to co-exist with equivalent structures. Further, rhizomes become especially beautiful and loving when they embody and/or voice the pluralism, multiplicity and complexity that is immanent in their devolved, flat, networked, non-individualistic structure, so that open/heterogeneous communities are broadly speaking more rhizomatic than closed/homogeneous communities because they have developed the principle of non-hierarchical flatness to its logical conclusion. All viruses are rhizomatic, but those that kill their hosts, such as the AIDS virus, are not especially beautiful or loving, which suggests that a straightforward celebration of the “viral” is politically limiting. It follows that human rhizomes must be assessed according to the same criteria and that the question must be asked: to what extent does human activity exist at the expense of other rhizomatic and non-rhizomatic structures? Human rhizomes have more potential than plant and animal rhizomes to form lateral relations across difference, yet if human rhizomes are to be beautiful and loving they must also have a planetary consciousness.

I would add that rhizomatic assemblages that include humans (or cyborgs, which are assemblages that combine the human with the animal or the technological) have the potential to intersect with a wide range of progressive positions that articulate a dynamic, non-fixed egalitarianism. Opposed to patriarchal culture’s rootedness in masculinity, the phallus and the experience of singular, centered sensation, a rhizomatic politics of gender and the body would be coherent with a feminist/queer politics that decentralizes the experience of non-genital sensation, and acknowledges gender and sex to be socially produced (as argued by theorists such as Rosie Braidotti, Judith Butler, Michel Foucault, Elizabeth Grosz and Donna Haraway). An equivalent rhizomatic politics of race would highlight the transracial interconnectedness of bodies, the non-privileged position of melanin in the human body, and the way in which diasporic networks generate hybrid identities (which would cohere with the work of critics such as Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hall). Because rhizomes are always in a process of becoming, a rhizomatic politics could align with queer and race projects that are anti-essentialist, i.e. articulate a non-fixed theory of identity, while the material character of the rhizome would militate against such a politics becoming overly reliant on the fanciful idea that being is merely a matter of postmodern discursive play. Of course human/cyborg rhizomes can possess a discursive dimension that has material effects, yet rhizomes are not exclusively determined by discourse because discourse does not frame the entire material world, so a rhizomatic politics should also be grounded in the material and the affective. In other words, sensation (music’s primary textural mode) must be considered alongside discourse (music’s secondary textual mode).

As I will go on to outline, Arthur Russell worked rhizomatically to the power of seven. First, he worked within a series of networks and prioritized the collaborative group over his own individual presence to the extent that he de-emphasized his own input. Second, his music-making methods were rhizomatic inasmuch as he democratized the decision-making process, encouraged co-musicians to improvise, immersed himself in editing, took to recording several versions of the same song, and valued the openness of live performance to the closed circuit of the commodified recording. Third, he made music that was aesthetically rhizomatic in that it was often decentered, loosely structured, non-hierarchical and non-teleological. Fourth, he worked across three broad blocks of sound ⎯ orchestral/composition music, pop/rock music and disco/dance music ⎯ and often worked on them simultaneously. Fifth, he worked with genres and sounds that were “non-despotic” and valued forms (such as pop, disco and hip hop) that were to varying degrees associated with the feminine, the black and the gay (i.e. the non-hegemonic). Sixth, he attempted to make connections between genres and sounds that were to varying degrees segmented. And seventh, as a result of these connections Russell helped generate the idea of an integrated downtown community (rather than a series of segmented, semi-autonomous scenes).

What follows is an initial outline of Russell’s rhizomatic politics ⎯ a politics that was concerned with the creation of an egalitarian, tolerant, integrated, non-individualistic artistic community (rather than an activist politics that argued and campaigned for the future introduction of such a community on a much wider scale). Russell did not develop his rhizomatic approach through individual study, but instead through a series of interactions that began in Oskaloosa, accelerated in San Francisco and reached their zenith in New York. He engaged with orchestral/composition music while in Oskaloosa, San Francisco and New York; he started to explore pop (in its loosest sense) in San Francisco, and then much more concertedly in New York; and he started to explore dance only after he had arrived on the East Coast. The rest of this chapter develops a condensed outline of those blocks, their relationship to the assemblages of Oskaloosa, San Francisco and New York, and their links to each other ⎯ at least as these relations were imagined and practiced by Russell. Because the thematic block approach creates an impression of generic order and relative separation that never existed in Russell’s day-to-day life, the blocks should be imagined as existing in parallel, even though can only be presented one at a time. Russell was respectful of the differences that existed between these blocks of sound, but the lines that ran between them also intrigued him, and whenever it was possible he kept sound in rhizomatic play.

a. Compositional Music

Arthur Russell’s primary musical affiliation as he grew up in Oskaloosa was with compositional (or orchestral/art) music. Suggesting a conservative outlook, his affiliation in fact constituted a rebellion against pop, the preferred music of his peers ⎯ “the jocks in school in the small town that I grew up in,” as Russell described them later ⎯ who liked to beat him up. After running away to Iowa City and then San Francisco, Russell enrolled in the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he studied composition as a part-time student, and also in the Ali Akbar College of Music, where he studied Indian classical music, again in a part-time capacity. Russell moved in tangents in both environments. The San Francisco Conservatory of Music became the avenue through which he started to take private lessons with an influential tutor, William Allaudin Mathieu, whose inspirations ranged from Nadia Boulanger (the influential French-born composer, conductor and teacher) to Pandit Pran Nath (the renowned north Indian vocalist), and during these lessons Russell focused on writing angular folk songs. Meanwhile, at the Ali Akbar College he persevered with his cello, a non-traditional instrument in this context, and looked to blend the aesthetic practices of Indian classical music (vocal techniques, the drone, devotional songs, rhythm cycles, etc.) with other musical forms. “He wasn’t letting anyone dictate to him that he needed to make a choice,” recalls Alan Abrams, a friend in the college. Russell pursued this dual track of Indian classical music and Western art music before he became aware of composers such as Terry Riley, who pursued a similarly unusual path in his attempt to overcome the formal conventions of Western art music. Signaling his intent, Russell featured the darbukka among more conventional western instruments in his first public concert, which was held at 1750 Arch Street in San Francisco in 1973.

In the spring of 1973 Russell decided to move to New York in order to develop a livelihood as a musician, and the following autumn he enrolled in the MSM, a prestigious launch pad from which to begin a career as an academic/composer. Situated uptown and embedded in the complex, intentionally alienated sounds of serial and post-serial music, the MSM failed to satisfy Russell’s desire to reach beyond the formal and social limits of the Western orchestral tradition. Russell sought out friendly alliances yet became perturbed by the way students were required to obey the aesthetic model set out by senior professors if they wanted to have a chance of pursuing a career as an academic composer. “He was having interesting problems with Charles Wuorinen [an influential serial composer who was based at the MSM],” remembers Christian Wolff, who Russell visited at Dartmouth during this period. “Wuorinen is this hyper controlling, rationalized serial composer, so he was completely at the other poll of what I imagine Arthur was interested in doing and what I was doing. The idea of him studying with Wuorinen blew my mind. They were at loggerheads the whole time.” On one occasion, when Wuorinen gave umbrage to one of Russell’s compositions, “City Park,” a repetitive piece that fused music with writings from Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein, Russell explained that he was excited by the way its non-narrative structure meant listeners could “plug out and then plug back in again without losing anything essential.” Wuorinen replied, “That’s the most unattractive thing I’ve ever heard.”

During his first semester Russell looked into the prospects of transferring to another college. Having spent an afternoon hanging out with John Cage the day after he arrived in New York, Russell got in touch with Wolff, one of the pioneers of indeterminacy, and thought about transferring to Dartmouth. That option appears to have become less enticing after Russell was invited by Wolff to play in a New York concert, at the end of which he met Rhys Chatham, the first Music Director of the Kitchen. Chatham was sufficiently impressed with Russell to persuade Robert Stearns, the director of the Kitchen, to appoint him as the venue’s next Music Director for the ensuing season, which ran from the autumn of 1974 to the summer of 1975. Having accepted the offer, Russell attempted to support other local and relatively low profile composers rather than build a program that accentuated the work of composers who were beginning to acquire an international reputation. His season opened with Annea Lockwood, a local musician, who performed “Humming: and Other Sensory Meditations,” a minimalist piece that invited audience participation. And the final concert featured Nova’billy, an upfront communist outfit led by Henry Flynt, whose wacky take on music and politics was not always respected by the serious end of the music market. It was left to Stearns to etch out a night for Steve Reich.

In rejecting the serial/post-serial establishment and exploring a line of orchestral music that has been variously dubbed “gradual music,” “phase music,” “process music,” “static music” and “minimalist music,” Russell joined a comparatively flat network in which the pioneering figures (especially Riley, Reich, Glass) were still young and lacked the authoritative gravitas that could come with an institutional base. Even though the aesthetic forged by these composers was still in its infancy, younger composers such as Chatham and Russell, as well as figures such as Peter Gordon and Garrett List, were not interested in repeating their approach, but instead sought to develop their own radical flights. “Arthur was very much influenced by the whole minimalist thing,” says List. “But we didn’t want to be minimalists, so we tried to find a way of dealing with it without jumping on the bandwagon.” Downtown’s compositional network was also flat because its participants sought to write music that would attract an audience ⎯ an outlook that had been dismissed by uptown composers, who were not overly concerned with their accessibility. “This [serial music] was seen as a complex music and the uninitiated listener was supposed to find it as difficult to understand as advanced physics,” notes Gordon, who developed a close relationship with Russell. “The composer’s ‘audience,’ therefore, was a small group of fellow composers, academics and aficionados. What we posited was a populist philosophy: new music could be composed which addressed both the sensual needs of the listener as well as the intellect. The audience for this music was seen as being the members of the community — artists, writers, neighborhood people.” Because the vast majority of downtown composers never had any money to put on shows, they regularly asked their composer/musician peers to volunteer their services, and a network based on an extended exchange of favors became the central mechanism through which new compositions got to be staged. Russell became a player in this network, playing for friends, who in turn participated in his own performances.

During his year as Music Director, Russell also staged a performance of Instrumentals, his first major composition. Although Instrumentals was notated, its modular structure allowed Russell and his co-musicians to select a range of sections to practice, after which they would listen to a tape of their efforts and decide collectively which blocks should be performed during the concert. This decentering of the author was embedded further thanks to Russell’s decision to encourage his musicians to use the notated score as a launch pad for improvisation, a move that signaled a further shift away from the stratified and hierarchical foundations of the compositional tradition. Drawing heavily on the basic standard era chord progressions that had dominated popular music during the 1930s and 1940s, the content of Russell’s provisional score contributed to the impression that he was deliberately distancing himself from the elitist underpinnings of compositional music, while the sheer length of the composition, which ran to a possible forty-eight hours, inevitably decentered the position of the composer, whose artistic intention would always remain fragmented. The introduction of an accompanying slide show (featuring nature photos taken by Yuko Nonomura) encouraged the audience and the musicians to assimilate the music in relation to the cosmos rather than the figure of the composer. Meanwhile, Russell conducted the concert in a deliberately low-key style in which he restricted himself to deciding when an improvisatory flight from the selected refrain had become so chaotic it was no longer feasible to continue. The clipped effect of these sections, some of which did not extend beyond thirty seconds, resulted in the performances out-popping pop in their sparkling brevity.

Glass believed Instrumentals demonstrated Russell was “way ahead of other people in understanding that the walls between concert music, popular music and avant-garde music are illusory.” (“There have been attempts from both camps to bridge the still very considerable gap between contemporary art music and the wilder shores of popular entertainment, with concerts by Peter Gordon at the Kitchen and some of the work of Brian Eno immediately coming to mind,” wrote Robert Palmer of a later performance in the New York Times. “Mr. Russell’s presentation, imperfect though it may have been, suggested not just a furtive embrace, but a real merging.”) Glass began to take a keen interest in Russell and, in his capacity as Music Director for Mabou Mines, invited him to play a cello piece during the theatre company’s performance of the Samuel Beckett radio play Cascando. A short while later, Glass arranged for Russell to compose the score for Medea, which was staged by the avant-garde theatre director Robert Wilson. (The high-profile commission appeared to mark a decisive turning point in Russell’s career as a composer, but Russell ended up falling out with Wilson and was eventually replaced by the British minimalist composer Gavin Bryars.) Glass went on to release Russell’s score for Medea on his own label ⎯ the piece was re-titled Tower of Meaning ⎯ and Russell followed this up with the release of Instrumentals, which came out on the Belgian label Les Disques du Crepuscule. The Wilson fall-out left Russell deeply disillusioned with the compositional world, however, and although he would go on to perform pieces for the cello at downtown venues such as the Kitchen and the Experimental Inter-media Foundation, he no longer harbored the dream that he could flourish as a composer of orchestral music.

b. Pop and New Wave

As a kid growing up in Oskaloosa, Arthur Russell held popular music in disdain, and when he moved to San Francisco in the late 1960s he steered clear of the city’s rock scene, which was so successful it was dominant (at least locally). Nevertheless Russell did start to compose avant-garde folk songs for the guitar and cello during this period, and he began to embrace pop music after hearing Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers play live in New York towards the beginning of 1974. That experience was powerful enough for Russell to decide to invite the band to perform across four consecutive nights at the Kitchen during his year as Music Director, and the following year he persuaded his successor to book Talking Heads. “Arthur’s unique contribution was to introduce rock groups to the programming, which was considered heresy at the time, but proved to be prophetic in its vision,” recalls Rhys Chatham. “I was shocked. But it made me think, and I ended up joining in.” Russell had come to appreciate that pop music as well as compositional music was engaged in a form of minimalism ⎯ or a pared-down repetitive music that could generate a transcendental experience ⎯ and in a 1977 interview with the composer-musician Peter Zummo he argued that pop was often ahead of the avant-garde in terms of aesthetic progressiveness. “In bubble-gum music the notion of pure sound is not a philosophy but rather a reality,” he told Zummo. “In this respect, bubble-gum preceded the avant-garde. In the works of Philip Glass or La Monte Young, for example, which are clearly pop-influenced, pure sound became an issue of primary importance, while it had already been a by-product of the commercial process in bubble-gum music.” Russell added that pop music’s commercial self-sufficiency enabled its practitioners to be honest and unencumbered, whereas avant-garde art music tended to generate pretentious discussions about value (including discussions about its superiority to pop and jazz) because its composers had to justify their right to be scheduled on aesthetic rather than commercial grounds.

The separation between the worlds of compositional music and popular music was so ingrained that even though the old Mercer Street Arts Centre housed both kinds of music, there was no point of interaction between the two sets of players. The cultures remained separate until Russell became interested in their points of intersection, and in a rhizomatic act he disrupted the institutional boundaries that existed between the two factions in order to demonstrate their overlapping aesthetic principles. The decision to programme the Modern Lovers and Talking Heads was Russell’s way of demonstrating that minimalism could be found outside of compositional music, as well as his belief that pop music could be arty, energetic and fun at the same time. “[F]or all of time painting has had the project of rendering visible, instead of reproducing the visible, and music of rendering sonorous, instead of reproducing the sonorous,” write Deleuze and Guattari, and the showcasing of the Modern Lovers and Talking Heads, like the construction of Instrumentals, was intended to render audible the lines that run between compositional music and pop. Within a couple of years the Kitchen was regularly programming rock-oriented performers, and two of its most prominent composers, Glenn Branca and Rhys Chatham, became significant figures in the No Wave scene.

Although Russell worked in a range of pop contexts during the 1970s and early 1980s, he consistently avoided anything that required him to either assume the role of the lead artist or sacrifice his desire to pursue other forms of music at the same time. When John Hammond invited Russell to record some demos at Columbia, Russell upset the legendary A&R executive (who had most recently talent-spotted Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen) by turning up not by himself but with a unique mix of pop and orchestral musician friends. A short while later, Russell appears to have stepped back from the offer to become involved with Talking Heads because he was afraid that the band was too self-consciously arty, ironic, cool and straight-suited for his looser, more Beatnik persona. Instead he developed a tight alliance with Ernie Brooks, the bass player from the Modern Lovers, and invited the drummer David Van Tieghem (who played with Steve Reich) and the guitarist Larry Saltzman (who came from a pop background) to form the Flying Hearts. The group recorded a series of light, quizzical songs that were full of promise but failed to win a contract with any of New York’s record companies, who were focused on the zeitgeist of punk and new wave. Seeking out a friendlier environment, Russell took up an offer to record with the Italian pop-rock outfit Le Orme, and when that did not work out as planned, he teamed up again with Brooks and joined the Necessaries, a new wave outfit that the bass player had joined following the break-up of the Flying Hearts. Russell helped the Necessaries win a recording contract with Sire, the cutting-edge new wave label, but he became disillusioned on a number of counts. First, the band’s pyramid structure prevented him from developing his own songs; second, the tight, fast aesthetic proved to be aesthetically restrictive; and third, the rigors of playing in a band that wanted to break through restricted his ability to participate in parallel music projects. Russell’s concerns ended up bubbling over during a promotional trip to Washington. As the tour van approached the Holland Tunnel ⎯ the symbolic staging post at which he would have left downtown New York in favor of a one-way journey into a recognizable sound, a life of on the road, and a requirement to devote all his energies to a single project ⎯ Russell decided that he had had enough and jumped out.

By the early 1980s, the exchange between pop/rock and new music was at its most intense, with no wave one of the most important sites of this exchange. “The no wave bands were at the borderline between art and pop, not only demographically (in terms of membership and audience), but also institutionally, insofar as they trafficked back and forth between art institutions (the alternative spaces) and seedy rock clubs,” notes Bernard Gendron. “Such sustained crossover activity between avant-garde and pop institutions was altogether unprecedented in the history of rock music or any American popular music, for that matter.” For all of its diversity, however, no wave regularly fell back on a series of aesthetic and performance strategies that were aggressive and even violent, and Russell appears to have been put off by the pressure to, in the words of his composer-musician friend Ned Sublette, simulate “the sound of World War Three.” Russell was too delicate and sensitive a soul to flourish in a scene that was charged by charismatic individuals and reverberant noise, and when the New York Rocker ran an extensive survey of the downtown scene that focused on the crossover between the art and rock scenes in June 1982, Russell did not feature, even though he had helped forge the early connections that culminated in downtown’s most popular point of crossing.

That did not deter Russell from playing and recording pop-oriented material in a barely traceable series of set-ups. He reformed the Flying Hearts with Brooks and other floating musicians and vocalists; he played in folk-oriented groups with Brooks and Steven Hall (who was introduced to Russell by Ginsberg in the mid-1970s and became one of Russell’s closest friends); he established a mutating improvisational/experimental pop outfit called the Singing Tractors that included Mustafa Ahmed (an African-American percussionist), Elodie Lauten (another composer-musician) and Peter Zummo; and he invited these and other musicians/vocalists to play on recordings of his own songs. “We would rehearse, get a set list out of Arthur, go on stage and have no idea what was happening,” recalls Zummo of Russell’s modus operandi with the Singing Tractors. “There was just no way to tell whether we were playing the songs in the order they were indicated on the set-list or not. He would just start going and you would have to make a decision, but it would be a difficult time to make a decision. That happened all the time.” The tangential explorations continued in the recording studio, sometimes to the frustration of Russell’s peers, who often did not know what they were working on, or when their contributions would be formally wrapped up. “Working with Arthur was not easy and not typical,” remembers Ahmed. “I worked for hours on tracks but never got the sense we were finished because of his constant editing. Anyone who worked with Arthur would tell you this was the most frustrating aspect about working with Arthur. He never seemed to finish anything. Arthur was never satisfied.”

Russell’s obsession with editing tape ⎯ of bringing separate sonic recordings into the same sonic continuum ⎯ culminated during the recording of World of Echo, which was released in 1986. “We would be mixing on a piece of tape and I would see a splice go by,” recalls engineer Eric Liljestrand. “It was all very confusing. I could never really tell what we were working on until it was done.” On the album, Russell’s cello playing accentuated affective range rather than virtuosic ability, while his voice, which had been subjected to the will of the instrumental tracks on previous pop recordings, discovered a similar freedom. Yet it was the interconnected quality of the voice and cello, which fused together like drifting gases, floating and merging until at points they were difficult to distinguish, that stood out. A shimmering, mystical celebration of vowel sounds, “Tone Bone Kone,” which would become the symbolic opening song of the album, expressed itself as textural affect rather than semiotic meaning, and for the rest of the album the songs evolved in meandering, mesmerizing threads, fluttering about in tender butterfly movements that were impossible to predict and would have been terrible to contain or discipline. “When I have written songs,” Russell wrote in some accompanying, unpublished notes, “the functions of verse and chorus seem to be reversed for some unknown reason.” The comment underestimated the extent to which structure was dissolved almost entirely, and Russell’s decision to blend all of the songs together into one continuous plateau where there was no beginning or end suggested that if listeners did not willingly abandon their bearings before listening the album would do this for them. The aim, Russell noted around the same time, was to “redefine ‘songs’ from the point of view of instrumental music, in the hope of liquefying a raw material where concert music and popular song can criss cross.” That made World of Echo the song-oriented successor to Instrumentals, which introduced popular forms into compositional music.

c. Dance Music

Arthur Russell did not plan to move into disco, just as he never planned to be blown away by the Modern Lovers, but having had serious affairs with two women, he started to date men, and one of them took him along to the Gallery, one of downtown New York’s underground private dance parties. Russell was inspired by the dance environment, in which a predominantly black gay crowd formed a material-spiritual body that built to an ecstatic peak through dance, and in so doing introduced additional sonic and affective layers (screams, whistles, whoops, smiles, bodily movements, etc.) to the vinyl selections. Integral to the Gallery assemblage was the DJ, Nicky Siano, who would select records in relationship to the mood on the dance floor, thereby extending and the world of recorded vinyl. The collectively generated selections created a profound impression on Russell. Arriving from a background in minimalist art and pop music, he was struck by the way in which 1970s dance music offered an aesthetically radical African-American variation of the stripped down minimalist sounds he was hearing in other parts of downtown. In addition, the economic viability of disco was established at a grassroots level, with the record companies providing free test pressings to DJs, who would in turn report back on their dance floor effectiveness, thereby providing the companies with valuable information about the commercial viability of their records. From 1976 onwards the importance of maintaining this link between the dance floor and the wider disco market was embedded further when record companies started to invite DJs to remix songs that were being lined up for release on the new disco format, the extended twelve-inch single, and DJs took to testing demo versions of these remixes with their dancers in order to gauge which parts required further work. It made sense, then, that Russell should be drawn not only to disco’s social milieu but also to the culture’s mode of music making, which was experimental, democratic and self-sufficient.

Teaming up with Siano, Russell started to record “Kiss Me Again” in November 1977, and he ferried reel-to-reel and acetate tests between the studio and the Gallery until Sire released the single towards the end of 1978. Although the track would turn out to be one of Russell’s more orthodox dance recordings, it nevertheless subverted a range of disco conventions. Running at thirteen-minutes, which was twice the length of a regular disco twelve-inch, “Kiss Me Again” stretched out into a mutating exploration of becoming-sound ⎯ and therefore encouraged dancers to do the same. Ordinarily figured as the smooth-running engine of any disco recording, the rhythm section ⎯ the drums, the bass and the rhythm guitar ⎯ was tripped up intentionally by Russell’s decision to deploy two drummers and two bass players, which created a subtle dissonance. And although the vocalist hoped to echo the typical performance of the disco diva, who would draw on soul and gospel techniques in order to deliver an assured performance that blended ecstasy, passion and pain, Russell aimed to destabilize her voice by inviting Siano (who was regularly high and had never entered a recording studio prior to “Kiss Me Again”) to produce her. The vocalist’s nervous delivery complemented the song’s lyrics, which recounted the story of a woman caught up in a S/M relationship ⎯ hardly the run-of-the-mill story of romance and resistance (or moving one’s body) that was so common to disco. Following the practice of cutting edge remixers such as Walter Gibbons, Russell observed the reaction of the dance floor to a series of reel-to-reel tapes and test pressings in order to ascertain how the record could be improved. A collective production that drew in a range of musicians, technologies and crowd responses in addition to Russell’s own musicianship, the record was released under the anonymous collective name of Dinosaur, even though it would have served Russell well to foreground his own name on his debut release. That, however, would have ignored the fact that the record was a product of the Gallery assemblage.

Russell accentuated the dance floor component in his next collection of recordings, which were released under the anonymous artist name Loose Joints. Whereas demos of “Kiss” had been used to test the response of the dance floor, this time around Russell invited dancers into the studio in order to channel the heightened affective atmosphere of the floor onto an original vinyl recording. Working in conjunction with Steve D’Acquisto, a pioneering New York DJ who he had met at the Loft, the incubator of the downtown disco scene, Russell invited a group of dancers to sing, play percussion and party alongside a number of the seasoned session musicians, and engineer Bob Blank, one of disco’s most experienced studio hands, remembers this being the moment he realized there was “a different vibe out there in the trenches.” “It was like a circus,” says Blank. “It was really important to let these people, who were regulars at the party, perform with the music because it was all felt.” Dominated by the regimented sound of European producers and the disciplinary R&B groove of Chic, disco’s aesthetic had become slick and heavily mediated by the end of the 1970s, but Russell hoped to develop a looser sound that was connected to the organic spirit of the down-town dance floor, and so he ensured that the established “profes-sionals” adapted their playing to the go-with-the-flow perspective of the dancer-musicians. Released under the studio name Loose Joints, recordings such as “Is It All Over My Face?” and “Pop Your Funk” featured drums that dragged behind the beat (instead of keeping the tempo precise or tight), jangly percussion, flat homoerotic vocals, street noise and ringing phones. Containing the plural voices of downtown disco, these and other records inspired by their uncon-ventional aesthetic combinations contributed to the adaptable resil-ience of downtown’s dance network during the national backlash against disco, which persuaded the US majors to slash their disco output in the second half of 1979, and were later judged to be seminal examples of “mutant disco” or “disco-not-disco.”

Russell’s next set of recordings, which were laid down shortly after the Loose Joints sessions, opened up disco not to the atmosphere of the dance floor but instead to the practices of downtown art music. A number of downtown composer-musicians (including Julius Eastman, Peter Gordon, Jill Kroesen and Peter Zummo) were invited to join the principle players from the Loose Joints line-up (the Ingram brothers and the Loft singers) and read from a detailed score of Cagean-like parabolas. Russell’s ambition, however, was not to reproduce the form of lavish orchestral disco that could be heard on labels such as Philadelphia International and Salsoul, but instead to develop a form of conceptual minimalism that, evolving out of Cage and Young’s principle of indeterminacy, commenced with the written score before opening out into an improvisational jam. Intent on illustrating the serious minimalist credentials of disco to the wider downtown compositional com-munity, Russell took a performance of his “orchestral disco” music into the Kitchen, and in so doing revealed the minimalist connection that existed between the downtown compositional and dance scenes ⎯ a connection that seemed unlikely to the scene’s more conven-tional composers, who (like many of their new wave peers) were skeptical about the aesthetic value of disco.

Russell’s dance productions were becoming more and more deterritorialized. “Kiss Me Again” worked with the refrain of a recognizable verse/chorus structure, yet opened out into the lines of flight of the rhythm section. The Loose Joints sessions also began with the text of a prepared song, although on that occasion Russell encouraged the musicians to develop a jam that was rooted in the improvised ethos of the dance floor. Then, with the orchestral disco sessions, Russell deterritorialized the dance and art spheres, after which he made a copy of the master tape and started to explore the infinite sound combinations that existed in the two-inch master tapes. Cutting and editing between the different tracks and sessions, the subsequent release, which was titled 24 → 24 Music, amounted to a vibrant, startling democracy of downtown sound that included a funk-oriented rhythm section, fusion-driven horns and keyboards, reverberant rockish guitars, and a range of voices (operatic/mono-tone/deranged/shouted). Appearing under the artist name Dinosaur L ⎯ a subtle but deliberate mutation of Dinosaur ⎯ 24 → 24 Music suggested a production that was rooted in reels and reels of multi-layered, twenty-four track tape that contained limitless immanent potential.

Russell continued to work as a lightning conductor of the downtown soundscape during the mid-eighties when he integrated Latin rhythms (which were ubiquitous on the streets of the East Village) and the looped breakbeat ethos of hip hop (which had made its way from the boroughs to the downtown club scene) into a series of dance productions. Working in collaboration with Ahmed and Gibbons, Russell released two standout twelve-inch singles, “Let’s Go Swimming” and “Schoolbell/Treehouse,” both of which developed a tidal polyrhythm of forward flows and drag-back undercurrents. Moving away from the disco-not-disco of “Is It All Over My Face?” and the avant-garde orchestral disco of 24 → 24 Music, the two records forged a form of jittery, jagged dance music that confounded easy categorization. “This is an impossible dance music, jumbling your urges, making you want to move in ways not yet invented, confounding your body as it provokes it,” Simon Reynolds wrote of “Let’s Go Swimming” in Melody Maker. “In its tipsy mix, I seem to hear Can, Peech Boys, Thomas Leer, Weather Report, hip hop, but really this is unique, original, a work of genius.” Having become habituated to the regulated sequencing of mid-eighties hip hop and house, New York’s DJs struggled to assimilate the unfixed contours of “Swimming” or “Schoolbell,” which left a disappointed Russell to forecast (correctly) that his broken-up aesthetic would eventually be “commonplace.” Instead of turning away from polyrhythm, however, Russell began to integrate black funk aesthetics into the pop recordings that he worked on right through to his death in 1992. The posthumous release of a number of these tracks on Calling Out of Context in 2004 provides evidence of a musical perspective that continued to draw together disparate influences while steering clear of rock music’s all-too-frequent disavowal of black music.

3. Deleuze and Guattari: Music, Composition, Genre

“This is how it should be done,” write Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in a passage in which it is difficult to not imagine Arthur Russell. “Lodge yourself on a stratum, experiment with the opportunities it offers, find an advantageous place on it, find poten-tial movements of deterritorialization, possible lines of flight, exper-ience them, produce flow conjunctions here and there, try out continuums of intensities segment by segment, have a small plot of new land at all times.” Having lodged himself in the downtown assemblage and experimented with the opportunities that were on offer, Russell became a notable “producer of flow conjunctions” in the wider downtown music scene when he introduced pop/rock into the heart of the downtown compositional scene, and forged a point of meeting between disco and the compositional scene. How, then, can his work be theorized in terms of its affective qualities, and, secondly, with regard to Deleuze and Guattari’s writings on music?

Music is especially rhizomatic because it is made up of sound waves that move through matter. Although light waves move more quickly than sound waves, they are less rhizomatic because they tend to be mono-directional (and can therefore be easily focused, as is the case with spotlights), whereas sound is omindirectional (and tends to spread, as is the case with a ringing bell). In addition, whereas light waves can move freely through air and transparent matter (glass, clear/shallow water, light plastics etc.), they cannot move through opaque material (earth, rocks, deep water, heavy fibres, etc.), while sound waves cannot pass through a vacuum, or non-matter, but can pass through everything else (which is why it is so difficult to insulate sound). The senses of seeing and hearing are similarly structured in that the seeing agent separates itself from the object of its vision through the eyes, which project the object as being in front and separate, and can also block out the object of vision with relative ease by closing its eyelids or averting its gaze. The hearing agent, in contrast, actively absorbs the sound waves of the object not only through its ears but its entire body, and this agent is unable to easily block out the object of sound, with the strategy of turning or blocking its ears of limited effect. In contrast to light waves, then, sound waves are structured according to their rhizomatic con-nectivity, and music, which is the cultural organization of sound, necessarily becomes a promising terrain for a rhizomatic politics. As Edward Said has put it, music has a faculty to “to travel, cross over, drift from place to place in a society, even though many institutions and orthodoxies have sought to confine it,” and this makes it materially transgressive (even if it might not always be politically progressive).

Early on in A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari note that music has “always sent out lines of flight, like so many ‘trans-formational multiplicities,’ even overturning the very codes that structure or arborify it,” and conclude that music is “comparable to a weed, a rhizome.” They go on to note that music begins with a refrain, after which its object becomes the deterritorialization of the refrain, the “final end of music: the cosmic refrain of a sound machine.” Whereas color tends to cling to territory, they add, sound is an effective deterritorializer, and music that breaks away from the refrain is invariably rhizomatic and therefore related to the process of becoming. “What does music deal with, what is the content indissociable from sound expression?” ask Deleuze and Guattari. “[M]usical expression is inseparable from a becoming-woman, a becoming-child, a becoming-animal that constitute its content.” In other words, music is a process of becoming-other that, in the words of Ronald Bogue, unfixes the “commonsense coordinates of time and identity,” in which the commonsense is figured in the man/ adult/human oppositions to woman/child/animal. The becoming, adds Bogue, does not involve the imitation of a woman/ child/animal, because this would enforce social codes, but “an unspecifiable, unpredictable disruption of codes that takes place alongside women, children, and animals, in a metamorphic zone between fixed identities.” In this respect, becoming-woman/ child/animal might be understood as a range of bodily expressions that get to be closed down by dominant heterosexuality and accordingly exist as an affective-material articulation of the sexual politics posited by queer theory.

Nevertheless Deleuze and Guattari do not romanticize music and note the dangers that lie within. Music can drag listeners into a “black hole” as well as open them to the “cosmos,” they argue, and since its “force of deterritorialization is the strongest,” it can also effect “the most massive of reterritorializations, the most numbing, the most redundant,” resulting in a “potential fascism.” What distinguishes a potentially democratic music from a potentially fascist music? Referring to Spinoza, a key philosophical influence on Deleuze and Guattari who maintained that the central issue of ethics was the ability to affect and be affected, Andrew Murphie argues that music becomes ethical when it is productive rather than anti-productive, when it sets free lines of flight rather than wears itself down through repetition that does not change, when it enables “movement and connection between different communities, different territories, environments, individuals” rather than erases difference and “allows both connection and escape from sovereignty.” Or as Bogue puts it, “The final ethical measure of any music is its ability to create new possibilities for life.”

Deleuze and Guattari stay close to the art music cannon in their discussion of music, with Boulez, Cage, Debussy, Messiaen, Schumann, Varése and Verdi cited for their becoming-ness, and the applause directed towards Boulez (the central figure in European serialism) for his work around “nonpulsed” or “floating” time that “affirms a process against all structure and genesis” might have puzzled the pioneers of minimalist music, who were clear about the way in which their aesthetic contrasted sharply with unapologetically elitist movement of serialism. In contrast to serialism, minimalism signaled a return to tonality (versus atonality), single notes (versus complex harmonic sequences), accessibility (versus difficulty), repe-tition (versus progression) and improvisation (versus music that was entirely scored). A choice had to be made: as Glass put it, European serial music was a “wasteland” dominated by “maniacs” such as Boulez and Stockhausen, as well as US proponents such as Babbitt, “who were trying to make everyone write this crazy, creepy music.” Deleuze and Guattari demonstrate that they do not feel bound by the ideology of serialism when they comment on Young’s “very pure and simple sound” and go on to celebrate the move “from modality to an untempered, widened chromaticism” before adding, “We do not need to suppress tonality, we need to turn it loose.” Elsewhere, they describe Balinese culture as an example of a rhizomatic plateau, or something that is always in the middle rather than at the beginning or the end, because it offers “a continuous, self-vibrating region of intensities whose development avoids any orientation toward a culmination point or external end.” That, however, does not lead them to highlight the way in which Balinese Gamelan formed the aesthetic framework for Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians ⎯ which debuted in 1976 and was considered his first major post-minimalist composition ⎯ and they are surprisingly hesitant when it comes to the rhizomatic potential of minimalism and post-minimalism given that this alternative movement had achieved a foothold in Europe by the time they published A Thousand Plateaus.

The suspicion that time and place cannot explain the omission of minimalism and post-minimalism from Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis is reinforced by the fact that the Belgian minimalist composer Wim Mertens published his own Deleuze-inspired account of minimalism in 1980 (the same year that A Thousand Plateaus was first published in France). In American Minimal Music: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Mertens draws a parallel between the Deleuzian concept of the decentralized work, which does not rely on teleological development and lies outside of history, and the goals of the minimalist composers, who generate “singular intensities” that are “ever changing and shifting” and have “no content” beyond themselves. Mertens analyses the way in which minimalist music shifts the listener’s attention from the content of change to the process of change. “In repetitive music this change is a kind of new content, and in a way one gets the suggestion of an entirely free flow of energy,” he argues. “The ecstatic state induced by this music, which could also be called a state of innocence, an hypnotic state, or a religious state, is created by an independent libido, freed of all the restrictions of reality.” In this Mertens rearticulates Jacques Attali’s analysis of the way in which minimalism’s “increase in libidinal intensity” compensates for the loss of historical content (the primary object of serial and post-serial music). “What is important is the shift of energy,” writes Attali, who is quoted by Mertens. “The intensity exists but has no goal or content.”

The striking absence of any sustained reference to minimalism/post-minimalism in A Thousand Plateaus is trumped only by Deleuze and Guattari’s failure to reference the entire field of popular music. Admirers of their theoretical work have stepped in to deploy the concepts of the rhizome, the assemblage, and the Body without Organs (which is described by Bogue as “a decentred body that has ceased to function as a coherently regulated organism, one that is sensed as an ecstatic, catatonic, a-personal zero-degree of intensity that is in no way negative but has a positive existence”) to a range of music genres. Tim Jordan analyses rave culture in Deleuzian terms and notes that dancers abdicate their subjective identity in order to merge into a collective body that resembles a Body without Organs. Simon Reynolds draws attention to the rhizomatic structure of the music of Can, Miles Davis, dub, hip hop, house and jungle. In a wide-ranging analysis of improvisation, Jeremy Gilbert draws attention to the way in which the groundbreaking jazz fusion albums of Miles Davis are “perfectly rhizomatic,” and argues that “music made through a non-hierarchical process of lateral connections between sounds, genres and musicians, which aims always to open onto a cosmic space, must be archetypically modern and rhizomatic in Deleuze’s terms.” In a separate piece, Gilbert also comments on the way in which Richard Dyer’s “In Defence of Disco” essay anticipated Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis of music by a year, and in so doing provided an example of a music culture that achieved the quality of a BwO more convincingly than any of the compositions cited in A Thousand Plateaus. In addition, Drew Hemment examines the affective modes of the electronic dance music assemblage, while Michael Veal notes the way in which dub has influenced applications of Deleuzian theory. A convincing case can therefore be assembled that Deleuze and Guattari’s theory not only could but also should be applied to popular music because it is there that it can find its most persuasive home.

The qualities associated with Deleuze and Guattari’s depictions of the rhizome and the BwO were certainly felt in music scenes that emerged in downtown New York during the 1970s and early 1980s. Mertens refers to minimalism’s ability to create a “hypnotic” or “religious” or “ecstatic state,” as well as an “independent libido, freed of all the restrictions of reality,” and all of these elements were prominent in the new wave scene that developed out of CBGB’s and the no wave scene that mushroomed soon after. At the same time, Mertens’s description seems to better describe the Gallery, where the DJ and the dancers embarked on a trance-inducing journey that, evoking the title of A Thousand Plateaus, would vary according to the shifting plains of affective intensity that were generated through the collective act of “playing the vinyl.” Mertens writes that repetitive music “can lead to psychological regression,” but it was on the floor of the Gallery rather than CBGB’s or the Kitchen that dancers whooped and screamed as they let go of their socialized selves under a sky of multicolored balloons. And while Mertens draws attention to the way the “so-called religious experience of repetitive music is in fact a camouflaged erotic experience,” it was at the Gallery that participants generated an unrivalled exchange of sensual movement.