David Mancuso and Louis Vuitton: Can they “Fall in Love”?

29 September 2022

With Lucky Cloud’s autumn party just passed, David Mancuso’s birthday around the corner and with my invitation to the NYC Loft’s Halloween party just arrived through the letterbox, I thought that now would be as good a time as any to reflect on the Louis Vuitton men’s fashion collection titled “Fall in Love”, which was launched during the summer, and in particular the company’s claim that the collection was inspired by David and the Loft.

That’s right. The team at Louis Vuitton, the flagship fashion house within LVMH (Moët Hennessy–Louis Vuitton), the world’s largest and most profitable luxury corporation, had a good, long think and concluded that it would be entirely reasonable to align itself with a person who paid almost no attention to his appearance, spent the very minimum on clothes, placed no value on material possessions (other than stereo equipment and vinyl!) and across the course of 46 years ran a house party that placed anti-commercialism and egalitarianism at the centre of its ethos. The development smacked of appropriation, or the process whereby a usually powerful person or organisation draws ideas from a marginalised, relatively powerless other and profits from the process, either in terms of money or cultural capital or both, with little or nothing trickling down to the original party—in this case the host of an actual party.

Hardly an aside, the designer of the collection is Virgil Abloh, the first Black artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s menswear collection; the most influential Black man employed in an industry that has a grim track record when it comes to promoting designers of colour; a provocateur who used his position to introduce a radical aesthetic into an often conservative sector rather than go with the flow; a significant player within hip hop culture who’d integrated hip hop aesthetics along with hip hop people into the fashion world; and a credible DJ who demonstrated a concerted interest in high-quality sound. Having conceived the collection, Abloh tragically passed away at the age of 41 in late November.

There are interesting discussions to be had about Virgil Abloh and his creative practice in relation to David. To what extent should Virgil Abloh feel free draw on the ideas and reputation of David without David being involved or represented? Given that Virgil Abloh held a powerful position within the fashion and music industry, how might he reasonably interact with the legacy of a party host who avoided and opposed corporate capitalism for his entire life? Does it matter if Virgil Abloh’s preferences around music and sound didn’t really coincide with David’s—because David had long become used to DJs and promoters claiming to have been influenced by him even though invariably believed their efforts diluted his practice? If the advancement of Black aesthetics through neoliberal culture comes at the indirect expense of the wider Black community is that a price worth paying?

But this isn’t about Virgil Abloh. Many people—some of them very hip, others less hip—have attempted to establish a connection with David. This has been going on for decades. And in this particular instance we can’t even be sure about the extent to which the collection was even his work, given that it his ideas—unspecified ideas, in the final instance—were put into practice by the Louis Vuitton creative team.

From the Louis Vuitton “Fall in Love” collection, 2022, as inspired by David Mancuso and the Loft.

What’s new here is the involvement in this process of a multinational corporation, in this case Louis Vuitton. That was my concern when I first heard about the collection and I’m absolutely certain that this would have been David’s overwhelming concern, because he never held anything against individual workers. I’d written the book that established the importance of David’s utopian-inspired contribution and I’d also worked alongside David co-hosting Loft-style parties in London for eight years. During that time David would regularly get upset when, in his eyes and to his ears, an individual or an organisation took advantage of Loft. During this pipers his concern was no doubt heightened because he and the Loft had fallen on hard times. If Louis Vuitton was claiming a seamless compatibility with David’s principles I thought I should comment on what appeared to be a blatant twisting of his intention.

News of the collection reached me when Tina Magennis—a dedicated regular at the Loft ever since David held his first “Love Saves the Day” party on Valentine’s Day 1970—sent me a link to a Mixmag article published on 26 July. The matter-of-fact report left me feeling uneasy, as did other journalistic accounts of the launch of the collection. There was no suggestion that Louis Vuitton’s alignment with David could be anything other than cool and positive, bringing a form of “deserved attention” to the Loft, with gratitude due to a fashion corporation that was forward-thinking enough to support the cause. I wondered: what about the Loft being the absolute inverse of everything Louis Vuitton stands for?

I turned to the “Fall in Love” press pack. In addition to the highly-stylised photographs of models wearing items that don’t resemble anything or anyone I’ve ever seen at a Loft party—of which a little more later—it includes a text that draws parallels between DJing and clothing design, paying homage to David Mancuso for the formative contribution of his Loft parties. “Through the eternal eye of Virgil Abloh, the job of a disc jockey is akin to that of a designer,” explains the text. Much is made of David’s political intent, from his commitment to civil rights, gender equality and queer rights to the way he hoped to transform the outlook of his guests through the selection of music. “Founded in a similar approach, the Louis Vuitton legacy of Virgil Abloh continually explores how the evolution of dress codes can be used as tools to promote ideas of anti-prejudice and egalitarianism,” the text continues. “Echoing Mancuso’s full-record sets, the ‘Fall in Love’ collection is constructed like a complete wardrobe.”

Although the text is short it contains several inaccuracies that David would have found extremely irksome. One of the more outrageous inaccuracies claims that David is popularly considered to have been the first DJ; a quick bit of research would have confirmed that DJing started to take root in New York City in the early 1960s and that beat-mixing pioneer Francis Grasso started out before David. But the inaccuracies are ultimately unexceptional and crop up regularly in pieces about the Loft. I’m more interested in two of the text’s most tendentious claims: first, that an innate synergy exists between clothing design and DJing (or what David preferred to think of as musical hosting—it’s a subtle but important distinction that unfortunately I won’t have time to get into here); and, second, that Louis Vuitton and David Mancuso share the same set of social values.

Can the art forms of clothing designing and selecting music at a dance party be “akin” to one another? Well, to a certain extent they can given that a significant number of contemporary cultural producers self-consciously draw on a wide range of historical influences in order to generate new forms of expression. However, it’s also hard to think of two process that are more different. One revolves around the visual, the exterior and the distinctive, encouraging us to look at ourselves. The other revolves around the aural, the interior (how music permeates our bodies) and the connective, encouraging us to forget about ourselves and interact with others through dance. One welcomes the presence of mirrors. The other breaks down if there are mirrors. Minor correction: the only mirrors that found their way into the Loft were the tiny ones that made up David’s spectacular mirror ball, itself a mesmerising object that drew dancers out of themselves and into the gyrating energy of the party.

With the mirror ball the unifying point, David selected music in conversation with his dancers so they could embark on a collective, unfolding journey that helped them to relax their egos and enter a heightened plane of consciousness that touched the vibrational, interconnected, material-spiritual essence of the universe. David spent a lifetime shaping the Loft to fulfil this goal. Is this what Louis Vuitton’s approach to clothing design is really about? Can we access the essence of what it is to be human, entering into a form of collective joy and maybe experiencing a form of cosmic transcendence, by putting on a pair of shoes, a shirt, matching trousers and a jacket? Is this what goes down in the changing rooms of Louis Vuitton’s stores? I mean, I’m always on the lookout for a good party.

We shouldn’t need to explain why this can’t be the case but apparently we do. Here goes. The act of purchasing clothing and in particular highly expensive clothing doesn’t contribute to the relaxation of the ego in a social setting organised around music and dance. Instead it reinforces the ego via a process that is largely individualised, from the moment of selecting an item to trying it on in front of a mirror to the look-at-me entrance into the kind of party where luxury clothes are worn. If the item happens to show the midriff we can say that it literally amounts to navel-gazing.

Yet the dubiousness of the argument that Louis Vuitton’s approach to designing clothes is similar to David’s approach to selecting music and hosting parties pales into insignificance when contrasted with the claim that Louis Vuitton has decided to release “Fall in Love” because, like David, it’s concerned with tackling anti-prejudice and promoting egalitarianism.

I don’t want to be unfair. The anti-prejudice claim is reasonable in terms of the relative diversity of LV’s regular employees, executives and catwalk models along with the boldness of appointing someone like Virgil Abloh to such an influential position in the first place. The company has some distance to travel until equality of opportunity is achieved but it record compares favourable with many other corporations. The anti-prejudice claim is less reasonable in terms of the relative homogeneity of its models, all of whom fit the industry-standard requirements around ableism, age, body size, conventions of beauty. But the real problem lies in LV’s claim to share David’s concern with egalitarianism. This is a deeply embarrassing claim that would have been offensive to David and must offend anyone who formed a deep connection with David and the Loft.

Let’s remind or ourselves of LVMH—fully Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, with Louis Vuitton one of the corporation’s most important and historic houses—and its place in the world. It describes itself as the world’s leading luxury goods group. It’s also the world’s most valuable as well as most profitable luxury brand. In 2021 it recorded profits of €17 billion, which was more than double 2020 and up 49% on 2019. Whereas David was at his happiest running an egalitarian party Bernard Arnault, the co-founder, chair, and chief executive of LVHM, appeared to be at his happiest reporting multi-billion profits to shareholders. As Arnault noted, LVHM had “enjoyed a remarkable performance in 2021 against the backdrop of a gradual recovery from the health crisis.”

Louis Vuitton report on results for the first half of 2022. Source

We should count our blessings that at least LVHM has recovered strongly given that during the pandemic incomes fell for 99% of the global population and over 160 million people were forced into poverty, with women, ethnic minorities and developing countries the hardest hit. During the same period the wealthiest people in the world—measured variously as the 1%, or the 0.1%, or the 0.01%, or even the 20 wealthiest people in the world (who between them own as much as the poorest 50%)—increased their wealth sharply. Already the beneficiaries of legislation that has favoured multinational corporations over other sectors of the economy during the last 40-plus years, LVMH investors have seen their shares rise by 170% over the last 5 years and 72% over the last three. Although the company is concerned about anti-prejudice, it operates at the heart of an economic system that systematises prejudice. Meanwhile its shareholders might well have spend some of the money they’ve accrued during the the economic mayhem of the last few years on jackets—and champagne.

If LVMH is serious about tackling prejudice and promoting egalitarianism in a spirit that connects with David then it would be reasonable to expect it to be able to attempt to follow the example of Warren Buffet, chair and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, who is the fifth wealthiest person in the world yet lives a remarkably modest lifestyle, https://www.mostinside.com/11-incredible-lifestyle-facts-of-warren-buffett/, and has donated $48 billion to charity. Bernard Arnault is the third wealthiest person in the world as well as Europe’s richest man, having generated most of his wealth through LVMH, and is currently worth $135 billion. How does he and LVMH compare?

There are no easy-to-find records of Arnault’s charitable donations as well as no easy-to-find reasons why Arnault might want to withhold information about his personal contributions, leaving us with one conclusion to reach. Arnault did spearhead LVMH’s donation of €200 million to the Notre Dame restoration fund back in 2019, although that cause generated a significant backlash thanks to the manner in which contributors seemed to be far readier to support classic French heritage rather than those most in need. LVMH also donated $11 million to fight wildfires in the Amazon, again in 2019. I wonder what “significant” contributions have been made since—significant is placed in quote marks because the total donated to Notre Dame and the Amazon doesn’t even come vaguely close to matching Buffet’s contribution—I make it less than 0.5%.

Admittedly LVMH has sponsored numerous art exhibitions as well as the building of the Fondation Louis Vuitton in the Bois de Boulogne, which cost 780 million euros. That’s a serious amount of money for a building, especially as the initial cost was set at 100 million euros. Then again, FRICC, a French anti-corruption group, went on to accuse the LV Fondation of deducting 60% of the costs from taxes and tax refunds, with LVMH also receiving €600 million from the government, turning the building into a version of corporate welfare (because the building is named after Louis Vuitton and contributes to the brand’s image and therefore profitability). “Corporate welfare” refers to instances when governments prefer to give handouts to wealthy corporations rather than those who are most in need or genuine public services.

What, then, did David make of the corporate world? Did egalitarianism matter to David? Was he concerned with economic equality as well as gender/racial/sexual equality? What might he have made of a tie-in with a corporation that targets an elite clientele?

We can take it for granted that David opposed racism, sexism and homophobia. He demonstrated on the streets for social change and he welcomed dancers of colour, women and queers into the Loft from the very beginning. Yet references to David’s opposition to discrimination routinely sideline questions of economic inequality, even though he was as concerned about economic discrimination as any form of discrimination. “David sort of prided himself on having a membership that was truly mixed; mixed racially, mixed ethnically, mixed sexually and, most importantly, mixed economically,” Mark Riley, a lifelong friend of David’s, told me. “You know, it wasn’t all rich people from the Upper West Side and middle-class people from Queens. Halston could be there and a homeless person could be there and they would all be treated with the same level of respect.”

David attempted to transcend class barriers within his party from the outset. He initially asked guests to pay $2 at the door—a contribution that might not have even covered his costs, which included organising a buffet, a punch made out of fresh fruit and the cloakroom, not to mention running and equipment costs. By the end of his time at 647 Broadway, the Loft’s first location, the price had gone up to $4 and by the end of the late 1970s it had risen to $12.99, in large part because the running costs at 99 Prince, where he reopened in late 1975, were exponentially higher. The entry fee hovered around $12.99 for the next couple of decades. “I never sold anything on the premises and I never allowed anything to be sold on the premises,” he told me while I was researching Love Saves the Day. “Everything was covered by the contribution. I tried to create a situation in which there was no economic inequality.” Because everything was included in the price, because dancers were free to bring their own bottle if they wanted to drink alcohol, and because David forbade his guests to sell anything (ie drugs) in his home, the Loft operated as a money-free space. This was of the highest importance to David, who believed that if the party was to become a space of utopian freedom and expression it had to exclude the use of money.

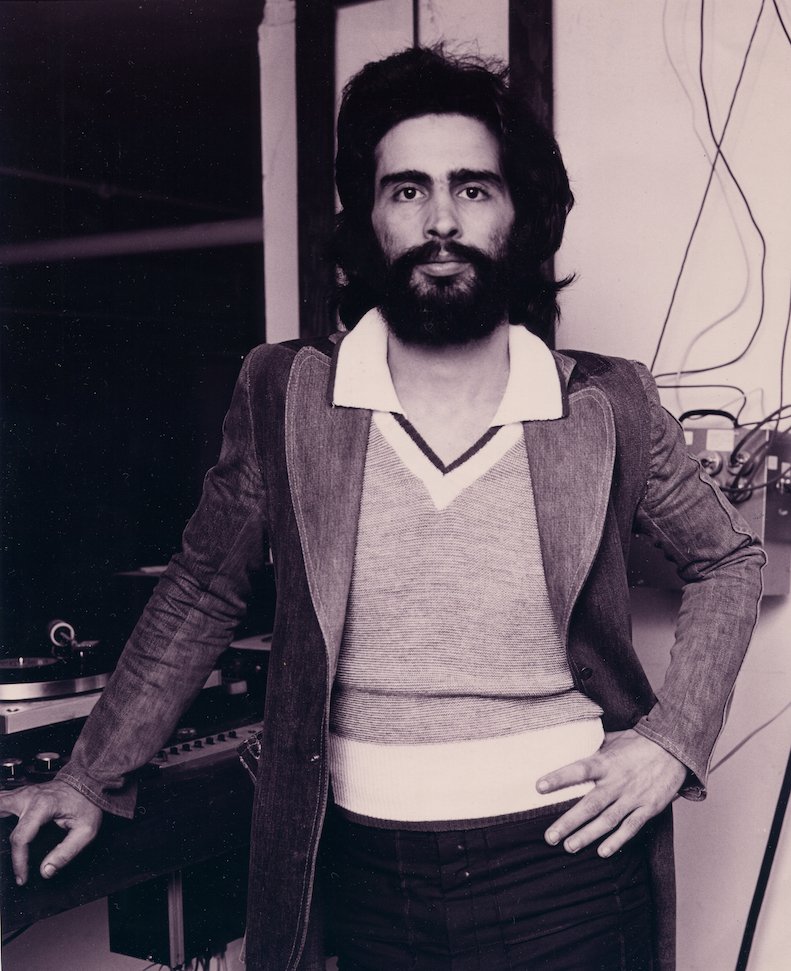

David Mancuso, 1975, photographed by Peter Hujar, courtesy of the Peter Hujar Estate. The photo first appeared in the Village Voice.

David kept on thinking up ways to make the Loft ever-more equal. He admitted guests even if they didn’t have any money; if they were broke a guest would write an IOU. Instead of trying to profit from the busiest time of the year, over Christmas and New Year’s Eve, David put on parties during the festive period for free. When he had to take tough financial choices about whether to operate a bar or not—for instance, he could have remained on Prince Street if he started to sell alcohol—he always refused the bar option on the basis that it would fundamentally alter the ethos and personality of the Loft. He always gave out his invite cards for free, because the idea of charging someone to attend a party in your home went against the spirit of the house party. When the Paradise Garage (the Loft-inspired private party that went on to be universally recognised to have been New York’s most influential underground venue, at least until I attempted to redress the balance somewhat in Love Saves the Day) introduced a fee for its membership cards and also set a higher entrance price for guests than members David objected, considering both to be a form of (in his words) “economic discrimination”. He objected to the very idea of a VIP and wouldn’t countenance supporting a venue that operated a VIP space.

David also lived according to a value system that opposed the basic operation of capitalism. In addition to the buffet, staff wages, utility bills, legal fees and internal work, David spent any leftover money on purchasing the best available sound equipment (which everyone got to enjoy) and taking friends out to eat. He barely spent any money on clothes. He sourced all of the Loft’s furniture from the street or local buildings that were being torn down, or had a carpenter build whatever else he needed. He travelled abroad only once between 1970-1998 (and hardly ever missed a Saturday night party between 1970 and 1986). In short, David lived according to egalitarian principles that in turn encouraged cross-class interaction to take place in his home. As he told the writer Andy Thomas, people were able to connect and “the vibrations became much freer.”

Although his main purpose in life was to create a little bit of social progress in his front room, David was also concerned with equality outside the Loft. Having participated in the civil rights and anti-war movements in particular he co-founded and offered free space to the first record pool, a DJ-led centre for the distribution of free promotional records, because he thought it was wrong that record companies should indirectly make money out of the low-paid DJs who not only brought their records but helped turn many of them into hits. He lamented the way that the corporatisation of disco, at birth an organic culture, led to a dilution of the sound and the experience. At some point he started to refuse to play bootlegged records on the basis that the recording musicians wouldn’t receive any proceeds. He once scolded a nephew when he picked up a dollar bill that was lying on the street, reasoning that it was possible that the person who’d dropped the dollar needed it to buy some food and might come back to look for it.

From the late 1990s onwards David’s anti-materialism was put to the test. As his good fortune and income declined during moves to Third Street (1984) followed by Avenue A (1994) to Avenue B (1997), Avenue B being the last home that was big enough for a party, friends and prospective partner-allies suggested ways he might revive his finances. David refused just about everything save for the proposal that he make and sell Loft T-shirts. I started to interview and become friends with David in 1997, around the time he reached his lowest point in terms of income. I always bought him lunch or dinner because it was clear that he was completely broke. As we spoke David explained that he couldn’t bring himself to compromise the core values of the Loft because the party was sacred to him and could be traced back to the earliest experience of growing up in a children’s home. David approached me (and Colleen Murphy, a close friend of his from New York, to start hosting parties in London) in part because I wasn’t a “party promoter”, or a professional party organiser, which for David strengthened the chance that the parties could revolve around passion rather than money (not that David underestimated the importance of what he liked to euphemistically refer to as “green energy”). During this period he began to accept invitations to work as a musical host in different countries and overall found it to be a positive experience that enabled him to spread the word while putting bread on the table and paying the rent. This was as far as David went in terms of compromising his vision of the Loft as a house party. Throughout the 20 years that I knew him he was always the most rigorously anti-commercial person I’d ever met within the party/club/music scene and industry. In 46 years of hosting parties—David passed away in November 2016 aged 72—he didn’t once advertise an event. Nor did he ever accept any form of sponsorship.

What about the clothes themselves?

Given that Louis Vuitton is concerned with egalitarianism, I should mention the price of the items that appear in its menswear collection (because however concerned LV is with anti-prejudice it didn’t release a Loft-inspired collection for women, and as for the trans community…). It turns out that jackets range from £2,000-4,750, jumpers are around £1,000, trousers £1,200, shirts £730-1000, and trainers and boots £590-1,280. I checked out the T-shirts, just in case there were any that were affordable, but they cost £575-750. I haven’t even spent £575 on clothing and shoes since the start of the pandemic, which contributed to me losing half my job. Not even remotely, now I come to think of it. Ah, hang on, Arnault once said: “Affordable luxury–these are two words that don’t go together.” Got you.

Turning to the collection itself, the “Fall in Love” text outlines some of the ways the items are supposed to capture and enter into a conversation with David and the Loft. “Echoing Mancuso’s full-record sets, the ‘Fall in Love’ collection is constructed like a complete wardrobe,” it opens, demeaning David’s practice while revealing nothing about the clothing. By the fourth of six paragraphs provides some specifics: paragraph to address the specifics of the range runs:

“A contemporary silhouette loosely informed by the 1970s cuts a lean line expressed in snug jackets and trousers that span the wide and the flared. Rollnecks and a red suede jacket play to that mood while hinting an idea of stagewear. Equalising dress codes, a two-button notch-lapel black suit mirrors the clubwear ease of a sculpted black tracksuit. Their properties meld into a logo-embroidered moleskin over-shirt and a formalised rainproof jacket with monogram topstitching. A technique likewise employed on leather jackets, topstitching appears in a distressed flower logo created in the image of soundwaves. Graphics promote the imaginary Louis Vuitton single Love Potion.”

Two more short paragraphs follow. The first notes that “shirts adorned in music notes nod to the parallels between sound and fashion” and adds: “Workwear covered in grease-effect paint motifs pays homage to the idea of the artist, a sentiment further expressed in bird prints featured throughout the collection as a symbol of freedom, both artistically and as the core of the universal values shared by David Mancuso and Virgil Abloh.” A passing phrase notes that “soft leather dancing shoes – created in loafers as well as oxford styles – are imbued with the wear of movement.” The second, which describes the “Fall in Love” bags, concludes with the following information: “A Record Canvas line in monogram takes inspiration from archive Louis Vuitton notebooks and evokes a vintage sensibility. Realised in blue, burgundy and dark green, it comes as a Keepall, a City Keepall, an Avenue Slingbag, a Christopher backpack, a Trio Messenger, and a series of small leather goods.”

When I first read the text I felt a strange sense of betrayal and I still do. From the very outset I’d been fairly convinced that Louis Vuitton’s attempt to associate itself with David and the Loft was inappropriate and I was unlikely to change my mind about that. What I didn’t expect was the rationale for the collection’s aesthetic choices to be so unbelievably thin and irrelevant. It was as if “Fall in Love” had nothing whatsoever to do with its supposed inspiration, meaning that anyone with even the tiniest amount of knowledge about David and the Loft would be unable to identify any links between the two. Music notes? Grease-effect paint motifs? Bird prints? Soft leather dancing shoes? A canvas bag that embroidered with LV that could conceivably hold five 12” singles rather than the 200-300 David would haul with him at great effort and discomfort during the late-in-life instances when he wasn’t able to host parties in his own home (when of course no record bags were needed)? None of this is specific to the Loft.

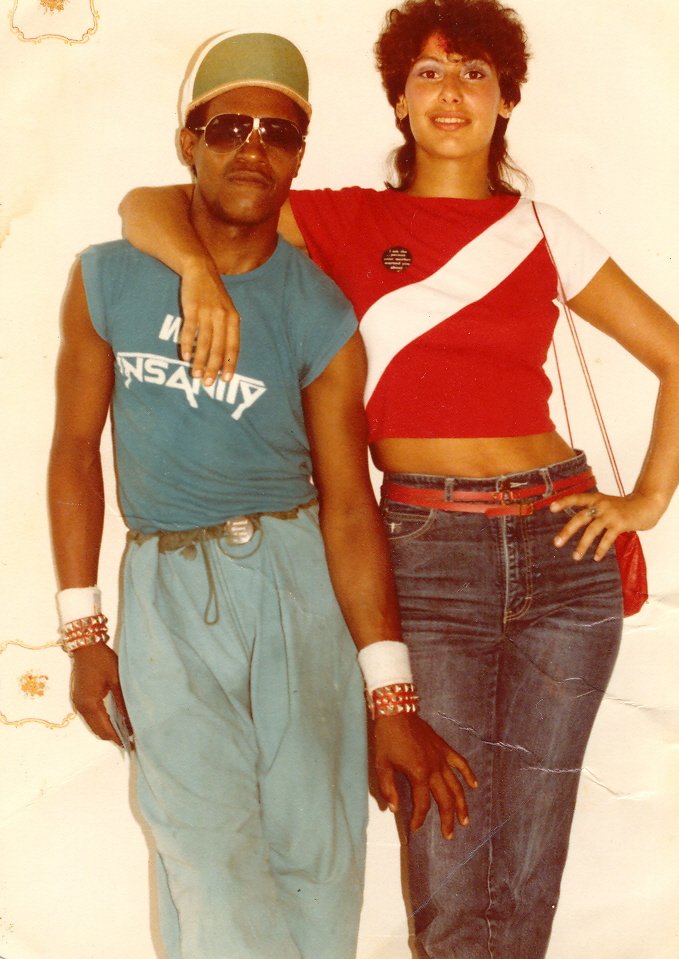

Louis “Loose” Key and Roxana Tash preparing to go to a party at the Prince Street Loft in 1982. Photographer unknown; courtesy of Louis “Loose” Kee Jr. As Loose described the clothing worn at the Loft during an interview I conducted with him for Life & Death on the New York Dance Floor: “We all wore the same kind of clothes, men and women—baggy pants, a T-shirt with shredded arms and sometimes beads. It was a fad. You’d have a T-shirt, you’d get a scissor, you’d cut the sleeves to make them shredded, and you’d put little beads through the shred so they would hang like braids. Some people used beads with different colours. The pants would be military-issue fatigue pants with a draw string on the bottom leg and a draw string at the waist. Some had pockets, some didn’t. They were usually in green. We wore them because they didn’t restrict the legs, so any movement that you wanted to try wouldn’t rip your pants. They were dark so you could roll on the floor all you wanted without getting dirty.” Loose continues: “Shoes: either Chinese slippers or Capezios. Capezio is the name of a shoe company that made a dance jazz shoe and most of the dancers would buy Capezios if they had the money or five dollar Chinese slippers from China Town if they didn’t. There were also these things called roach clips, or alligator clips, which we used if we smoked a joint. They had a long bird feather stuck on one end. Sometimes the feathers were attached with suede string and beads. It clipped on your body as an ornament and it was used when your marijuana cigarette got down to the roach, so you wouldn’t burn your fingers. This was all fashion mixed with function. It wasn’t about fancy style. The style was urban street wear. A lot of the movies we were watching were blaxploitation movies and martial arts movies, and the martial arts movies had a lot of kicking, flexibility, fighting, and you'd see all these gangs also wearing baggy pants and shredded t-shirts. People dressed creatively and practically. You wore something that was comfortable and durable.”

The disjuncture between the items as they are photographed in the Louis Vuitton publicity and the clothing that dancers tended to wear to the Loft is even greater. From the outfits shown in 20 shots I can imagine maybe one pair of trousers and one shirt making it to the Loft dance floor without making the wearer look like a tourist. It’s not just about the obvious practical limitations of the outfits; their tone is also all wrong. The publicity claims that the collection has been shaped “through memories of the legendary Loft”, but there’s no evidence of any history being evoked here. The outfits are unrelentingly cool whereas the Loft was unrelentingly warm. The models are upright, stiff, vacant and unsmiling, and so capture nothing of the welcoming, joyous energy that defined the Loft as soon as you passed through David’s front door. The setting for the photo shoot attempts to replicate an ex-industrial aesthetic that could have worked but doesn’t, in part because the floors are concrete rather than wooden. I’m not sure if downtown’s industrial infrastructure began to go concrete before Dean & DeLuca opened what was once its flagship store in 1977, although maybe some art galleries went down that route at an earlier point. Probably. Anyhow, David always made sure that his dance floors were made of wood. Cool vs warm, again and again, in what amounts to a complete disconnect, and this in a clothing collection that wants to demonstrate an affinity with a party that was all about connection.

The point isn’t whether the “Fall in Love” collection is cutting-edge or beautifully tailored within the wider terms of the fashion industry. (I think that most of the items look awful—their not even wierdly exciting—but can’t offer an informed judgement on this.) The point is whether the collection’s contribution to clothing intersects with anything that might have been worn at the Loft, and the short answer is that it doesn’t, not by a long way.

As Louis “Loose” Key Jr., a regular dancer at the Loft from 1980 through to the present day, put it in an interview I conducted with him for my third book, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983: “The Loft wasn’t about your dress and attire. It was about being communal.” As Loose explained to me, dancers wore functional T-shirts, military-style gas pants, and either Capezio jazz-dance shoes or five-dollar Chinese slippers. Many shredded the sleeves of their tees, threading beads onto the shred so they hung like braids. Some also attached an alligator clip adorned with a long feather to part of their clothing as an ornamental smoking accessory for when their joints burned down to the roach. “People dressed creatively and practically,” he noted. He also told me that the Loft was the “complete opposite” of Studio 54, where regular theme parties are staged for the likes of Giorgio Armani, Yves St. Laurent, Valentino and Gianni Versace, dancers would buy expensive outfits in order to be somebody and narcissism reigned supreme. Now there was a dance venue that could have matched Louis Vuitton’s synergistic intentions.

Early into his time in New York, after he started to earn some money, David began to buy clothes and wanted to look good, as did many of his peers (which is a story for another time). “If you see the way I dressed in early pictures, I was like a real Italian kid from upstate and I talked like one, too,” he told me. Queer photographer Peter Hujar’s shots of David from 1975, taken for a Vince Aletti feature about the Loft published in the Village Voice, present the party host as handsome, groomed, calm, focused and suave. That day David wore a well-cut jacket, a collared V-neck jumper and what look like nice-fitting trousers. Maybe David’s Italian look was still in its heyday although it’s more likely that he dressed up for the occasion. David had, after all, been forced to stop hosting parties in his 647 Broadway space in June 1974 and his next move took him to 99 Prince Street, located in the heart of SoHo. Bruised by the closure and determined to establish the Loft on a secure legal footing, especially because the rent and costs at 99 Prince Street were significantly higher than they had been on Broadway, David applied to the city for permission yet faced concerted opposition from the SoHo Artists’ Association. As he told me: “One woman turned to me at my hearing and said, ‘David, if I try and sell my space and the buyers look out of their window and see n****** and spicks…’ That was what she said. I thought she would say, ‘Car traffic.’ […] The fact they called themselves artists was a cover-up for people who were there to buy buildings and gentrify the area in a narrow direction. My survival was at stake.” So David made sure he looked respectable for the photo shoot.

As David settled into Prince Street his style became very relaxed. His standard outfit consisted of a T-shirt or a collarless cotton shirt plus slacks. When it came to spending money, David prioritised staff wages, rent and stereo equipment, with clothing probably bottom of the list. When David went to Warners for a Record Pool with Mark Riley he wore odd socks and no shoes—the receptionist apparently looked at him warily, wondering if it would be necessary to call security, until he confirmed who he was, at which point he was ushered to his meeting like a king. The staff a Lyric Hi-Fi, the Upper East Side hi-fi shop where David began to purchase the most advanced stereo equipment known to the world in the late 1970s, tried to figure out why someone who was ready to spend thousands of dollars on a single cartridge would show up looking like a tramp.

David wasn’t being downwardly-mobile or attempting to cultivate some kind of image. He just didn’t believe that clothing was particularly important. From the time I met him some 20 years later to the time he passed away almost 20 years after that David would wear construction boots (during one trip to London he dived into a builders’ merchants store so he could buy a new pair), loose-fitting and usually well-worn jeans, a T-shirt and on top of that a regular shirt that was usually chequered. That was all he ever wore, and he didn’t dress differently if he was meeting up with a friend for lunch or musical hosting at a party. His greatest show of vanity involved him dying his hair. At the same time his ultimate aspiration was to be able to perform his duties at a party without being the focus of attention because if that came to pass it would mean that dancers were focused on dancing with one another and the party would go higher. In short, David showed almost no interest in clothes and as it happens he also had next to no money to spend on clothes for the last 32 years of his life. It wouldn’t have occurred to him to introduce a dress code at the Loft because he hated restrictions and he hated the idea of excluding anyone from his party.

In case the obvious needs to be stated, there’s nothing wrong in turning to clothing for comfort or to look good or to express oneself individually or as part of a wider group. Many people, including people who live on the margins of society, find particular succour and joy in clothing. We all participate in the ritual of putting on clothes every day of our lives. We are the only animal on the planet that needs to wear clothes in order to survive. Yet putting on clothes is categorically different to dancing to music, and what significance there is in putting on clothes changes when the clothing ceases to fulfil a straightforwardly practical function or express the soul, or when the soul that the clothes express is rooted in extreme wealth along with the dead end if not outright problematic ideas of exclusivity and even superiority. And that’s what Louis Vuitton brings to the catwalk, the shop floor and the changing room, because if the corporation’s items weren’t exclusive the company couldn’t charge the astronomical prices it gets away with. “Luxury goods are the only area in which it is possible to make luxury margins,” Bernard Arnault once commented, revealing his business model.

Before anyone complains that I’m picking on Louis Vuitton or LVMH, let me acknowledge that the company is nothing more than a massive conglomerate in a wider neoliberal economy that has resulted in corporations becoming ever more wealthy and powerful as we the people become comparatively poorer and the world teeters on the brink (or has already slipped over the brink) of ecological catastrophe. It can be tricky critiquing corporations. They dominate the world in which we live to the extent that many if not the majority of the technologies, banking services, energy sources, pharmaceuticals, clothes, food and drink, and media and entertainment companies that we use on a daily basis come to us via corporations. This wasn’t the case 50 years ago and could have hardly been imagined when the Mesopotamian shekel, the first known currency, emerged 5,000 years ago, never mind when modern humans first emerged in African about 300,000 years ago, never mind the 13.7 billions years that have elapsed since the Big Bang. We are led to believe that without corporations life is unimaginable, that their presence is inevitable and something we should embrace. History suggests otherwise, with social dance far more intrinsic to human existence, forming the glue that first persuaded humans to group together in order to survive, as Barbara Ehrenreich argues in Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy. Yet here we are today, living in a world where we are routinely informed that there is no straightforward way to live outside of neoliberalism, and Louis Vuitton is by no means the only player.

David Mancuso at the Light, London, June 2005, on the day we, Lucky Cloud Sound System, introduced our newly-purchased Klipschorns to the party. This was David in his standard outfit--a shirt, a T-shirt, trousers, socks--minus the chunky trainers/boots. Photograph by me.

Corporations go to extreme lengths to persuade us to love them and Louis Vuitton is a corporation that many have grown to love. It creates beautiful products that it sells through seductive fashion shows, models and advertisements that some find awe-inspiring. It feeds into widely-shared fantasies of a heightened aesthetic lifestyle where the problems of financial hardship and scarcity don’t exist. Its employment practices exist at the comparatively progressive end of corporate culture. It has employed creative, cutting-edge designers, with Abloh the most revered and notable. And yet the stark reality remains that it is one of the world’s most powerful corporations, operating in one of the most profitable, inflated and exclusive sectors of the global economy. This doesn’t straightforwardly make it any worse than other corporate players and the damage it causes is less overt than the damage wreaked by gas and oil companies. At the same time its focus on clothing and the wider luxury market makes its attempt to establish a connection with David and the Loft particularly distasteful.

Would David have accepted money, even a large sum of money, from Louis Vuitton in return for the use of his name in a clothing range? It’s impossible to imagine him saying yes. Anybody who knew David would understand just how problematic he would find Louis Vuitton’s framing of the Loft. Other questions follow. Did Louis Vuitton request permission from David’s cousins or the board that has overseen the affairs of the NYC Loft, an ongoing party and community, since David passed away? Thinking also about Virgil Abloh, to what extent have we been presented with his vision of a Loft-inspired collection given that he died before its completion? Did he have much or even anything to do with the material that accompanied the release of the collection? The PDF that outlines the collection ends with a very brief overview of Louis Vuitton, the man and the company, and concludes that “audacity has shaped the story of Louis Vuitton.” Audacity: that sounds like a good description.

Louis Vuitton’s synergy with the Loft was always obviously superficial. Nobody could have ever believed that its intention was to build a meaningful, sustained relationship with the culture of the party and its legacy. It merely wanted its customers to experience a form of vicarious access that wouldn’t involve them changing their lifestyles. The point was to make them feel as though they were cool, connected and, somewhat strangely (given that the Loft got going in 1970) on the pulse as well as vaguely politically progressive, which seems to boil down to not being overtly racist, sexist or homophobic. Next month’s collection was always going to sell them a different set of cultural references.

At the same time Louis Vuitton isn’t just part of a corporate economy that can co-opt culture on a whim while maximising its profits and contributing to the acceleration of inequality. It’s also part of an industry that, for all of its insistence that it loves us, has had a directly negative impact of David and the Loft. After all, David held his final party on 99 Prince Street in June 1984, having been priced out of an area where rampant retail alongside multi-millionaire loft living was taking root. David ended up purchasing the Pilgrim Theater on Avenue C in the hope that it would provide the Loft with a permanent home. He had become frustrated with the lack of a genuine community in SoHo, concluding that local artists often came from real estate families who could see how purchasing the area’s buildings would turn into an investment bonanza. A move to the Lower East Side, where immigrants had developed roots for decades, would provide the Loft with a much more conducive setting. Government money had also been promised to help regenerate a historically poor neighbourhood that had also become the drug capital. But Ronald Reagan cancelled the regeneration in order to prioritise military spending and tax cuts for the wealthy, leaving David to enter into a war zone. A slow, calamitous decline followed until David was left with more or less nothing.

Meanwhile Prince Street and SoHo became a giant shopping centre, or the absolute inverse of what the Loft was (and still is) about. Occupying the cheaper end of the fashion market, J Crew turned 99 Prince Street its flagship store for 21 years. Since late 2018/early 2019 Moncler, whose prices parallel those of Louis Vuitton, has occupied the space. I did wonder for a moment if Louis Vuitton owns Moncler, because Arnault’s strategy has apparently been to acquire as much of the luxury market as possible. Not yet, it turns out.

Arnault, however, knows what it means to “Fall in Love”, especially with a rival luxury brand, and declared that the recent $16 billion acquisition of Tiffany was “just the beginning” as he extended LVMH’s array of luxury houses to 70, including 14 in retail and fashion. It might not come to pass, but if LVMH purchases Moncler Arnault could hold a launch party in the store and, given the history of 99 Prince Street, organise it around the theme of the Loft. Guests could be encouraged to wear “Fall in Love” outfits, donning music notes, grease-effect motifs and birds prints to show just how much they appreciated the Loft. If David Mancuso were alive he could have been the guest DJ. And at the peak of the party he could play “Love Potion”, the imaginary Louis Vuitton single.

Only that David would have said no.