I Hear Music in the Streets: New York 1969-1989

La Fabrica, 2025.

Edited by Guillermo M. Ferrando, text by Tim Lawrence

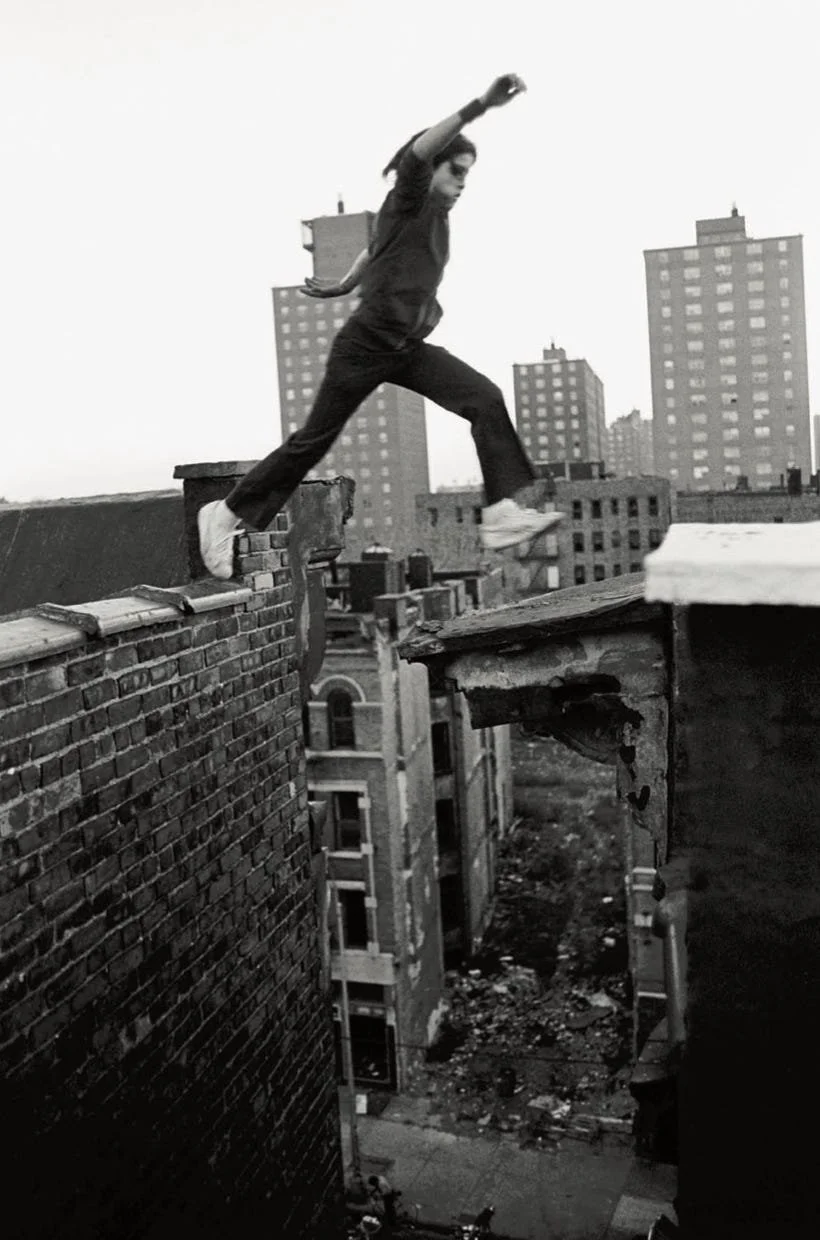

New York in the 1970s and 1980s, mythology has it, was a crumbling, crime-ridden, garbage-swamped disaster zone, a hellhole where nobody in their right mind would want to live. Matters came to a head as early as June 1975, when police and firefighter unions published a pamphlet with a bold “Fear City” headline that warned tourists not to visit and to take extreme caution if they did. In October the city teetered on the brink of bankruptcy. Asked to offer support, President Ford told the city to “drop dead”, or something along those lines. The collapse was complete and it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that the city began to properly recover.

This version of New York history has been repeated so many times it’s become common sense. Yet the photos included in this book depict a city that, far from enduring a catastrophic and humiliating fall, brimmed with humanity, energy, even joy. A photograph can be made to depict just about anything, but in this instance there’s no deception at hand. The selection process was tough because of an overabundance of options. Digital photography wouldn’t properly break through for another 20 years or so, yet the archives contain such consistently rich and inspiring images it’s easy to conclude that New York during the 1970s and 1980s must have been the most enthralling and beautiful place to live on earth, dilapidated buildings and all.

Spanish Harlem, 1988. Photo: Jose Rodríguez.

The gap between appearance and reality is simple to understand, the reasoning just isn’t very popular with the corporate status quo that executed a de facto coup d’état in the city in 1975 and from there rolled out a radical programme of economic liberalisation, tax cuts for the wealthy and cuts to the public sector, eventually across significant swaths of the planet. New York, through no obvious fault of its own, became the petri dish where the experiment was trialed, at least in the West.

During first six decades of the 20th century, when the city established itself as a global leader in terms of culture, finance and international politics, there were few indications that New York would become the site of a right-wing coup. The 1960s, however, witnessed a western-wide slowdown in industrial production, a collapse in tax revenue, a decline in public services and the onset of the urban crisis. Ongoing white flight, or the mass abandonment of the city for the suburbs by the white middle-class, further reduced the city’s income. Having attracted internal Black American and Puerto Rican migration during the 20th century, New York became a definitionally racialised city, especially after the 1965 Immigration Act ended the systematically racist favouring of white migration into the US. Many white people masked their prejudice with tales of family values and self-pity.

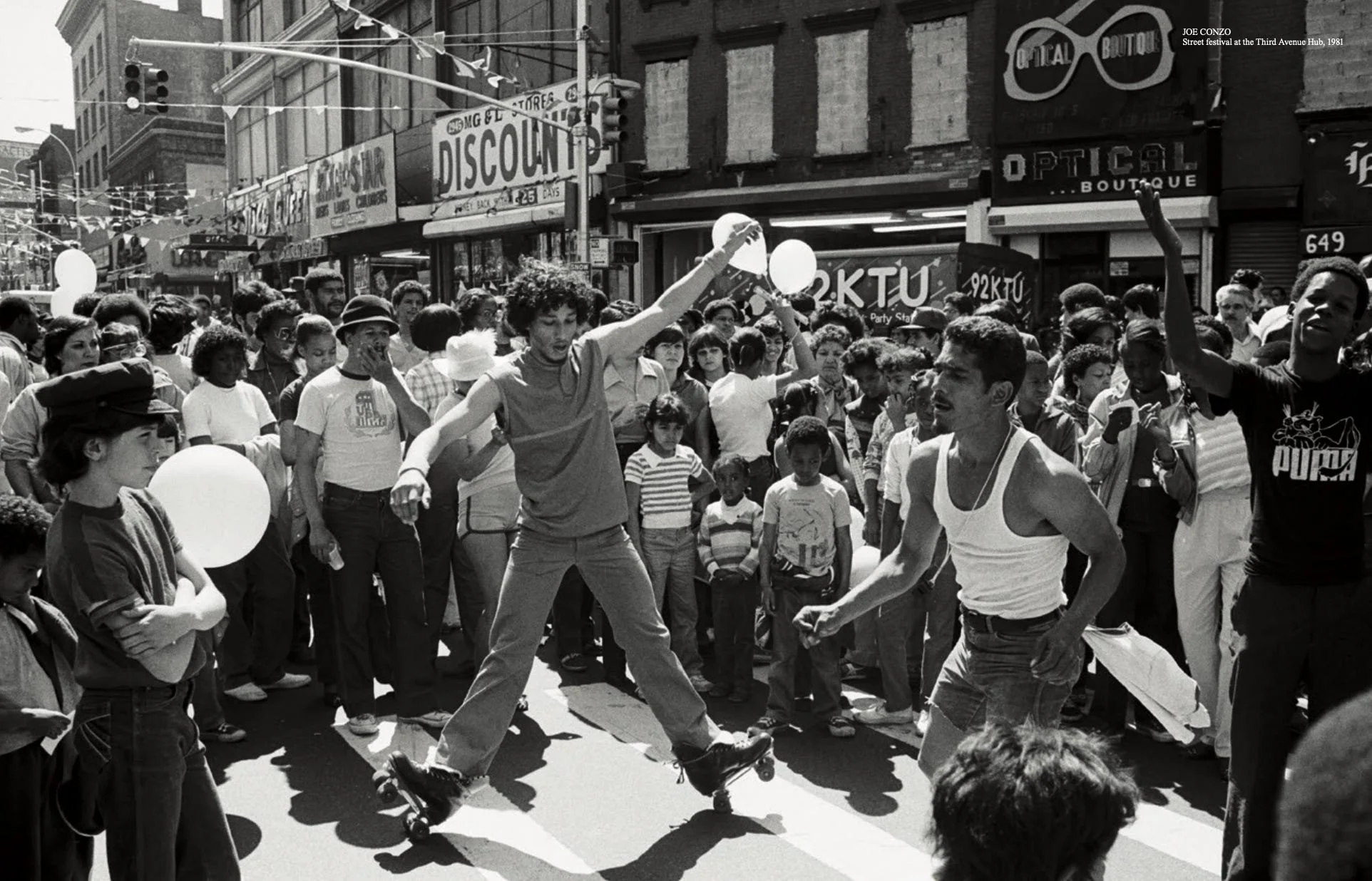

Street festival at the Third Avenue Hub, 1981. Photo: Joe Conzo

John Lindsay, the startlingly progressive mayor who held office from 1966 to 1973, rode the storm. Besieged by challenges on his first day in office, he pronounced that New York remained a “fun city”. On the night of Martin Luther King’s assassination he travelled straight to Harlem and formed an indelible bond with the Black American community. Instead of cutting jobs he created jobs. The city’s population discovered a new voice. In the summer of 1969 alone three major events—the Stonewall rebellion, the Harlem Cultural Festival and the New York-populated Woodstock festival—accelerated new forms of collectivity. Meanwhile the civil rights, Black power, gay liberation and countercultural movements carried the promise of renewal and equality.

The economic challenges nevertheless only intensified during the opening years of the 1970s as growth slowed and absenteeism spiralled. The oil crisis and ensuing recession of 1973 confirmed that capital needed a new way to maximise its return now that colonialism, slavery and industrial capitalism were exhausted. Chile’s General Augusto Pinochet, whose coup d’état of September 1973 was covertly supported by the US, trialled a way forward: economic liberalisation combined with trade union and wider social repression. By the time New York City ran out of money in October 1975 President Ford, Nixon’s unelected successor, knew what needed to be done and refused bailout money.

Stripped Chrysler, South Bronx, 1970. Photo: Camilo José Vergara

Disavowed by the federal government during the most intense period of its inevitably tumultuous transition from an industrial to a postindustrial economy, New York became hostage to the demands of the banking sector. From this point on, a cabal of powerful financiers started to dictate the terms of public policy and ushered in an unprecedented round of austerity in return for earmarked money. For the economic and urban geographer/historian David Harvey, the corporate seizure of democracy marked the birth of neoliberal capitalism.

The ideological shift required a good justification story to and served a jacked-up parable that revolved around just how awful it was to live in New York City during the 1970s. Ideologically jacked-up by a corporate class that needed to reign in the social democratic ethos of the city, the story of deepening challenges met with willpower was turned into story of spiralling doom. Garbage piled skyscraper-high, the urban terrain became uninhabitable, the act of stepping outside one’s front door amounted to a gamble with mortality, a cataclysmic collapse in social relations left the city all but lifeless, collapsed in the gutter of shame. City Hall and social democracy to blame.

Yet the lived experience was of a city that flourished under deliberately generated duress. After all, it was during the 1970s and much of the 1980s that New Yorkers conjured their most compelling and enduring contributions to art, dance, music and transformative ways of living. They also moved and interacted in a way that led the city to finally fulfil its melting pot promise. Meanwhile the city entered its first and last period of sonic dominance, or an environment where music and sound rather than visual culture define how people experience their day-to-day lives in a way that emphasises connectedness, not separation. There was music in the streets and it shaped an era.

As the middle class moved out and new waves of migrants moved in, New York became the embodiment of a working-class city. Residents escaped cramped living conditions by spending increasing amounts of time on tenement building steps and in the city’s streets, parks and beaches as well as bars, hangouts and nightspots. As they did this fresh forms of entertainment emerged to offer fun, respite and catharsis, making the city newly communitarian, expressive and relevant.

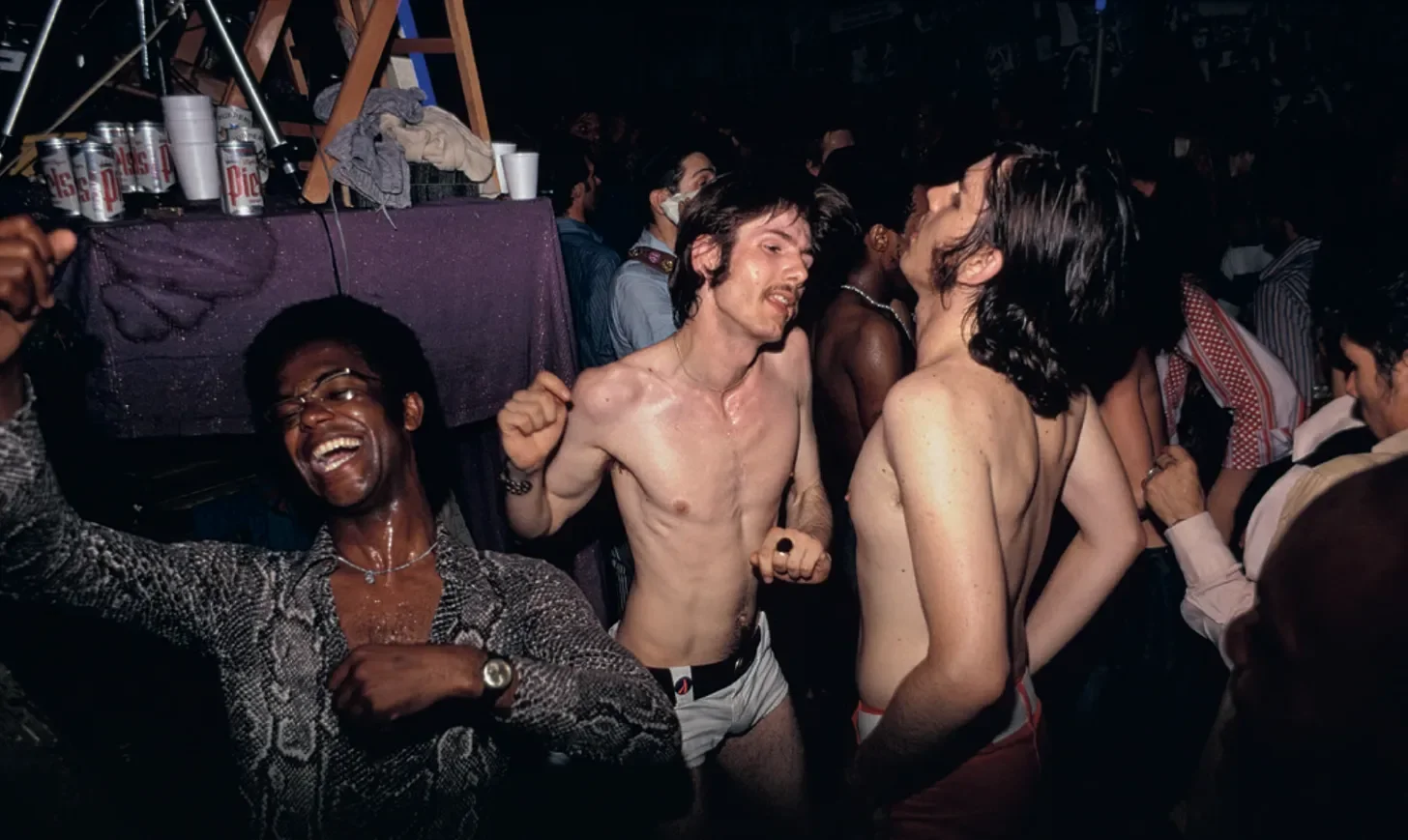

Sonically and socially confined during the 1960s, DJing flourished thanks in part because it amounted to a definitionally cheap form of entertainment. The practice discovered its transcendent potential when the relentlessly utopian David Mancuso started to host weekly invite-only parties in his downtown loft—soon dubbed the Loft—that bypassed New York’s restrictive cabaret licensing laws. High-end stereo equipment and open-ended music selections shaped a crowd that seemingly encompassed every vector of social identity, including class. Meanwhile two gay entrepreneurs called Seymour and Shelley took over the Sanctuary, a failing Hell’s Kitchen discotheque, and became the first owners to welcome the city’s LGBTQ community into the venue’s newly and definitively diverse mix. Liberation, love and LSD fuelled the night.

Dance at the Gay Activist Alliance, Firehouse, 1971. Photo: Diana Davies

From this point on DJing became an interactive art form that was rooted in Black American antiphonal/call-and-response aesthetics. Rock is routinely considered to be the ultimate musical expression of the countercultural movement, yet the revitalised practice of DJing—a form of musicianship that was improvised, unrepeatable, non-commodifiable, anti-individualist, democratic, sonically integrationist and reality-stretching—amounted to a more radical break with the status quo.

During the opening years of the 1970s private parties and public discotheques mushroomed in downtown New York, Fire Island and in pockets of commercial midtown. A mobile discotheque scene also flourished in Brooklyn and Harlem as well as the Bronx, where DJ Kool Herc started to host parties with his sister in the recreation room of their Sedgewick Avenue home. Herc shaped a yet-to-be-named approach that overlapped significantly with the wider DJ scene save for his preference to perform alongside MCs.

Kay Gee of the Cold Crush Brothers, Harlem World Club, 1981. Photo: Joe Conzo

The DJs who worked in these spots drew together whichever danceable recordings they could lay their hands on: rhythm and blues, soul, funk, gospel and rock along with recordings featuring African musicians (much of it recorded in Europe) and some homegrown Nuyorican salsa (much of it released on the breakthrough Fania label). In the autumn of 1973 music journalist and Loft regular Vince Aletti published an article in Rolling Stone that charted the rise of DJ culture and described their heady range of their selections as “discotheque music”. During 1974-75 a loose amalgamation of these sounds began to circulate as a new genre called disco.

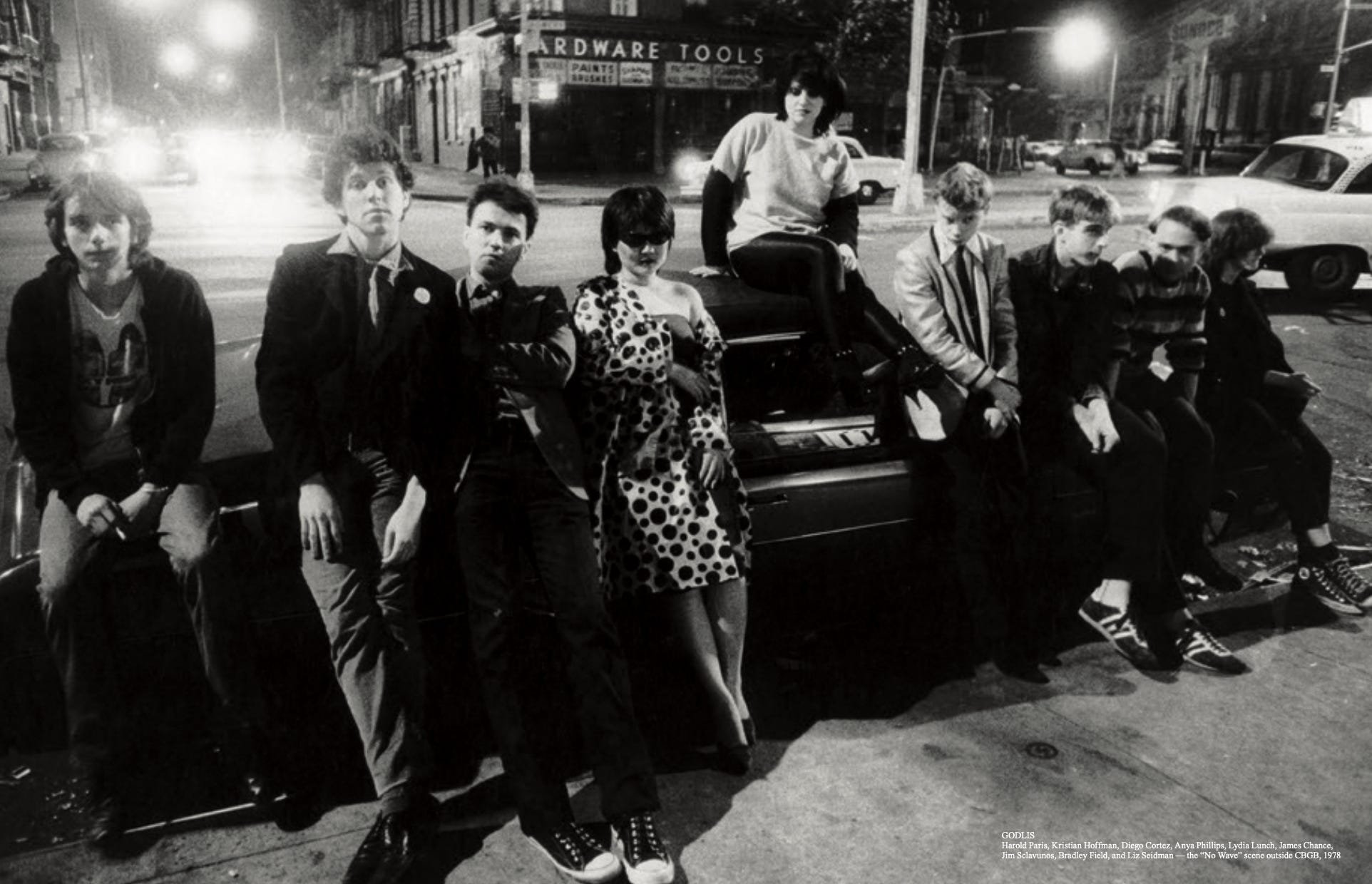

All the way through rock bands performed wherever they could find an audience, from the Fillmore East to Tompkins Square Park to the Oscar Wilde Room in the Mercer Street Arts Center. In 1972 the New York Dolls and other line-ups started to thrash out an artistic version of stripped-down rock, later described as proto-punk. When the Mercer Street Arts Centre collapsed in the summer of 1973 the band scene relocated to CBGB on the Bowery. In 1974 their sound came to be known as punk, even though the name never quite captured the scene’s artistic intent.

Determined to flee what they considered to be the stifling, conservative, materialistic lifestyle of their parents, a breakaway generation of young suburban refugees gravitated to downtown’s flourishing band and creative art scene. Even if participants moved to a different rhythm than those who frequented the parallel DJ scene, they were similarly grassroots in their outlook. Those with some money moved into the deindustrialised warehouses of SoHo and NoHo. Those who had no money went to live in the neglected tenement enclaves of the East Village.

Left to right: Harold Paris, Kristian Hoffman, Diego Cortez, Anya Phillips, Lydia Lunch, James Chance, Jim Sclavunos, Bradley Field, Liz Seidman, outside CBGB, 1978. Photo: GODLIS

If anything the city’s cultural production accelerated in the aftermath of the fiscal crisis. Blondie, the Ramones, Talking Heads and Television struck recording deals with on-the-ball labels. Bronx DJs stretched out the practice in terms of musical breadth (Afrika Bambaataa) and technical wizardry (Grandmaster Flash). Having introduced an element of salsa into disco, as its name promised it would, Salsoul became the first label to commercially release a 12” single, a new format that allowed remixers to meet the energy of the city’s dance floors. Musicians, producers and remixers—most notably Black music devotee Tom Moulton and the technically and emotionally radical DJ Walter Gibbons—stretched out disco’s ecstatic potential.

A period of commercial overdrive, media fawning and social exclusivity followed when Studio 54 opened in midtown in the spring of 1977. Later that year the Brooklyn coming-of-age disco movie Saturday Night Fever ratcheted up disco’s visibility and established the groundwork for its mass popularisation and dilution. Yet the city still jumped, still moved, still seemed to know no bounds. When a power cut interrupted a Loft party Mancuso invited dancers to tune their boomboxes into the same local radio station and continued the dance ritual via candlelight.

Rafael, thirteen, the Bronx, 1977. Photo: Stephen Shames

Punch-and-Judy history has it that punks and disco became mutually antagonistic during the 1970s and through their opposition discovered meaning. However they barely knew of each other’s existence until 1976 and during 1978-79 Hurrah followed by the Mudd Club and Club 57 opened as so-called punk discotheques while ushering art exhibitions, fashion shows, video and film screenings, immersive happenings and performance art into New York’s dance milieu. The Mudd Club’s Anita Sarko became one of the era’s most daring DJs. Music didn’t divide, it brought people into contact with one another, encouraging scenes that had barely formed to overlap.

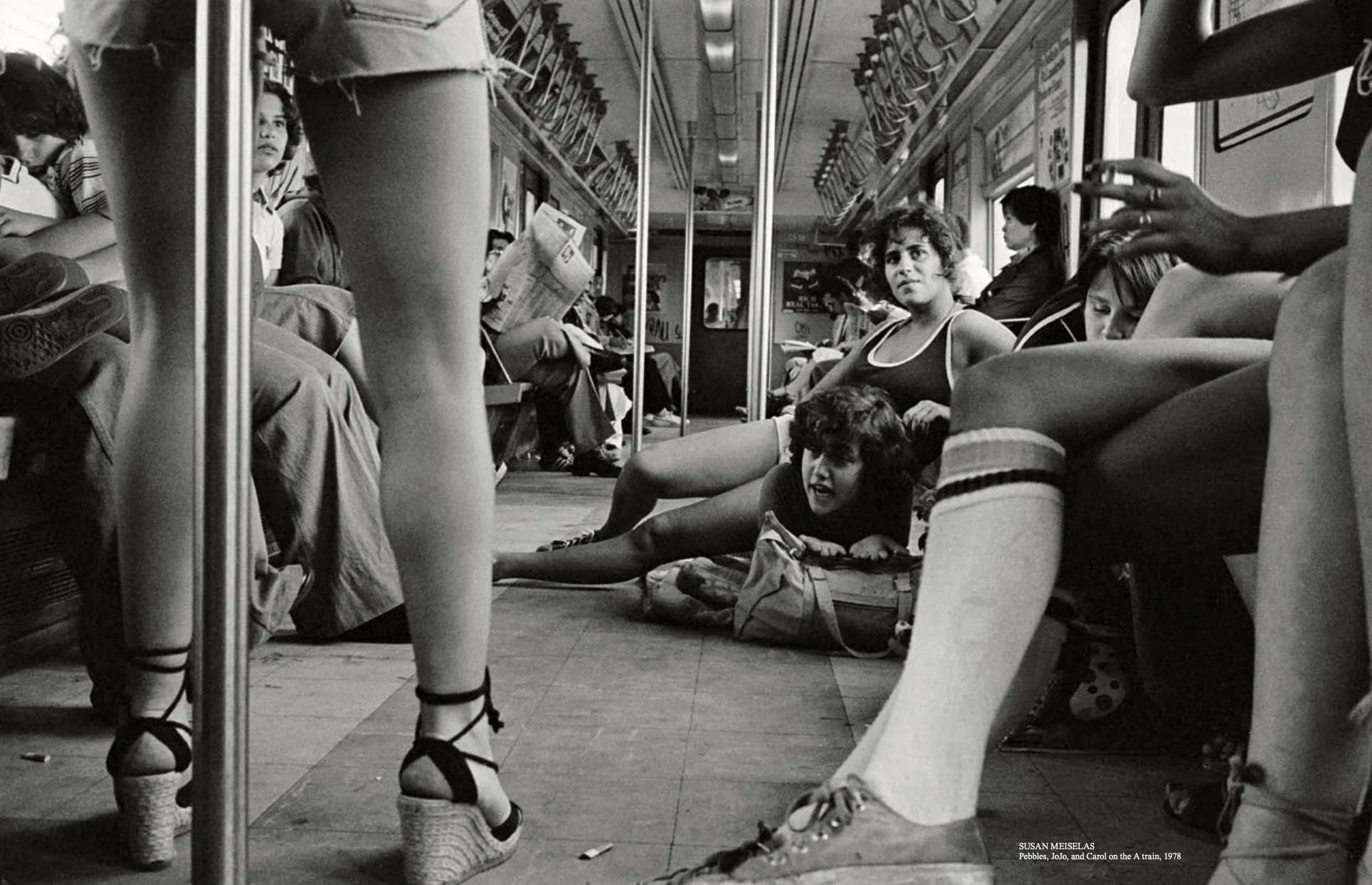

More than any time before or since, music seeped through every nook and cranny of the city. Discotheques and party spaces established new circuits of connectivity as they multiplied. Boombox culture exploded as New Yorkers took to playing their favourite music as they moved through the city’s streets. WBLS and several other local radio stations fed the fever. On weekends Central Park hopped as dancers gathered to start or continue a party. The subway pulsed with beats on top of screeches as brakes halted wheels.

The A Train, 1978. Photo: Susan Meiselas

None of this evokes the unliveable city of popular mythology. Of the more than 300 people I’ve interviewed about life in New York during the 1970s and early 1980s, no one told me they considered leaving because of the much-reported crime and drudgery. Quite the opposite was true; they didn’t want to go away, even for a weekend, for fear of missing something extraordinary. “It was like Halloween every night,” recalls Club 57 organiser and performance artist Ann Magnuson.

Community interaction and expression became heightened because New York was open and affordable. If the challenges and struggles rooted in moving from industrial to post-industrial capitalism were real, New York’s multiracial working-class citizenry was already used to navigating poverty, racism and violence. The city remained a fun place to live.

Peaking in the summer of 1979, the backlash against disco didn’t symbolise a breakdown in social and music relations, at least not in New York. Instead it created space for a grassroots rejection of the commercialisation of the sound by downtown and Bronx DJs alike. As the corporates withdrew from a recently-lucrative market, spurred on by a simultaneous downturn in the economy, city’s DJs, musicians and dance crowds breathed a sigh of cathartic release. If anything they now moved with ever-greater freedom and expression.

For all the talk of impending collapse, the 1980-83 period amounted to the most significant cultural renaissance of the twentieth century. Art, contemporary dance, no wave film and experimental theatre continued to invent new ways to experience and imagine the world. Yet it was the extending music scene that continued to define the personality of the city.

Moving beyond join-the-dots containers of disco and punk, the soundscape became funkier, rootsier, more hybrid, less orderly. The definitively adaptable genres of rap and dub entered the matrix along with synthesisers and drum machines, which breathed fresh sounds and energy into the circuitry. Reviewers took to describing new releases with hybridised monikers to capture the era’s rapidly evolving sound combinations.

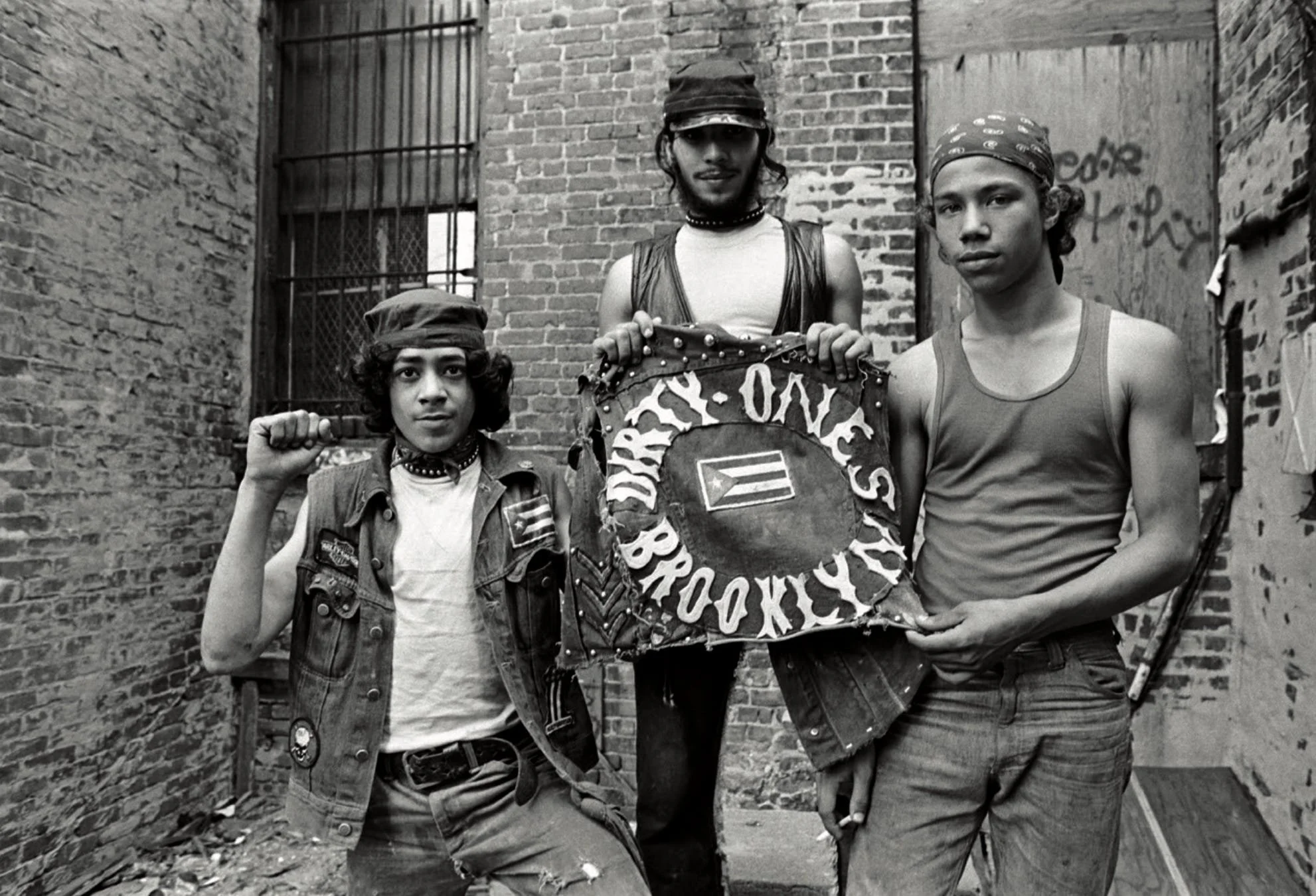

The Dirty Ones, Brooklyn, 1978. Photo: Donna Svennevik

Tens if not hundreds of thousands of people went out to dance or listen to music every week. At the Paradise Garage, DJ Larry Levan, a Mancuso acolyte, took collective joy and amplified sound to a new level of body-shaking intensity. The white gay dance scene reached its own unprecedented crescendo at the newly-opened Saint. The art-punk scene expanded its reach with the opening of the multi-floor Danceteria. Shimmering, upbeat, embedded in the moment, “I Hear Music in the Streets” by Unlimited Touch became an anthem across the city’s dance floors.

Graffiti burst onto the downtown scene in simultaneous wonder. Artists Jean-Michel Basquiat, Fred “Fab Five Freddy” Brathwaite, Keith Haring, Lee Quiñones quickly discovered they shared the downtown art scene’s devotion to cutup, collage, intertextuality, juxtaposition, DIY and use of found objects as well as the desire to refuse constriction. In the autumn of 1980 Brathwaite teamed up with downtown filmmaker Charlie Ahearn to make a movie about graffiti that ended up integrating the art form with Bronx-style DJing and MCing plus breaking—or the combination that would be named hip hop in 1981. That same year the Mudd Club hosted the breakthrough “Beyond Words” graffiti exhibition and downtown actress Patti Astor opened the Fun Gallery as a showcase and hangout for all.

Emerging in the background, however, the onrush of neoliberalism interrupted the carnival. Property prices soared by 15 percent per year from 1983 while Wall Street climbed at its fastest rate since the 1950s. As corporate welfare (tax breaks) took effect and the white middle class began to return to the city, gentrification and nimbyism—or the habit of new inhabitants bringing not-in-my-back-yard suburban values with them—took root. City Hall responded by intensifying its regulation and surveillance of nightlife, with the Paradise Garage elbowed into closing. Artists who could no longer afford to pay the rent started to move out of Manhattan, sometimes as far away as Williamsburg.

Working-class communities of colour also found themselves under attack. Cuts to welfare, introduced by Ronald Reagan, elected president in November 1980, disproportionately impacted the Black American and Hispanic population. The subsequent spread of crack, a cheaper and more potent form of cocaine, intensified the crisis. Racist legislation that made crack-related offences 100 times more punishable than for the powdered cocaine favoured by wealthier consumers resulted in the mass incarceration of Black men.

Puerto Rican Day Parade, 1981. Photo: Arlene Gottfried

Meanwhile, HIV/AIDS, first reported in 1981, reached epidemic proportions in 1983 and accounted for the death of almost 20,000 New Yorkers by the end of 1989. Ed Koch and Reagan more or less ignored the crisis while the media stoked homophobic fear. Scores of influential figures from the art, dance and music scene passed away, among them Alvin Ailey, Michael Brody, Keith Haring, Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe and Klaus Nomi.

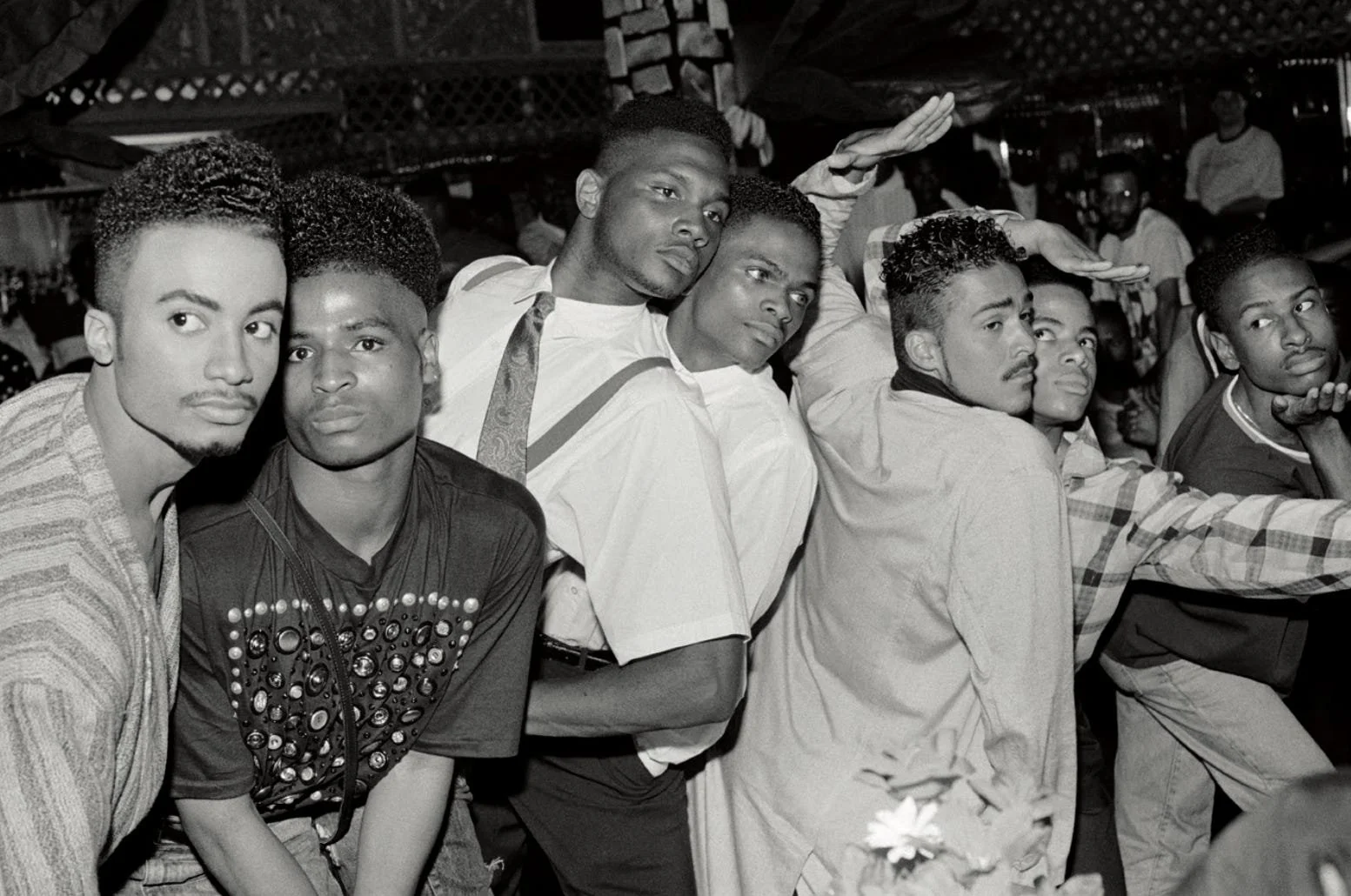

Any one of these developments would have had a huge impact on the city’s social equilibrium. Their simultaneity prompted fragmentation as the city’s increasingly interactive multicultural, polysexual, cross-class population became more insular. From this point on music releases tended towards aggressive realism (hip hop, hardcore punk) or hopeful utopianism (house). Steering a hybrid path, ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) formed in 1987 in a swirl of AIDS activism, resistance, pride and fearlessness. Populated by working-class, competitive, expressive, fierce drag queens of colour, a vibrant Black and Latin ballroom scene channelled endemic precarity into expressive community, bursting out of the fault lines to deliver an angular earthquake.

Left to right: Whitney Elite Garçon, Ira Ebony Aphrodite, Stewart LaBeija, Chris LaBeija Revlon, Ivan Adonis Chanel, Jamal Adonis Milan, Roland LaBeija. At the House of Jourdan Ball, 1989. Photo: Chantal Regnault

Overall the city’s scenes became more distinctive, separated and at times mutually disdainful than anything that had unfolded during the 1970s and early 1980s. The city’s grassroots populations also became less relentlessly innovative. The heady era of convergence faded to a memory.

Since 1994 the city has kowtowed to the priorities of corporations and the super-rich rather than its historic communities. Mayor Rudy Giuliani rolled out “quality of life” / “broken windows” / “zero tolerance” policies that revolved around a police crackdown on allegedly disorderly, low-income citizens who occupied public space. His successor, multi-billionaire Michael Bloomberg, mayor between 2002 and 2013, extended the purge, rezoning thousands of city blocks for luxury and corporate usage as well as overseeing an increase in the stop-and-frisk surveillance of minorities, especially young men of colour. New York became a more policed, regulated, sanitised city, and it hasn’t altered direction that much since.

The reengineering deserves to be challenged. According to Bloomberg, in 2008 the federal government poured at least $7.7 trillion—$1.31 trillion in 1975 terms—into the banking sector to help it surf the catastrophic debt it had created, yet this hasn’t prompted a reconsideration of the refusal to support the city during its far more modest fiscal crisis. Today the city’s debt of just under $100 billion is 50% higher in real terms than the peak debt of 1975, yet nobody cries Armageddon. By May 2024 almost 350,000 millionaires lived in NYC, the most of any city in the world, up almost 50% on 2015. The corporate sector claims to have saved New York from itself but its fairer to say that it hijacked the city in order to save itself.

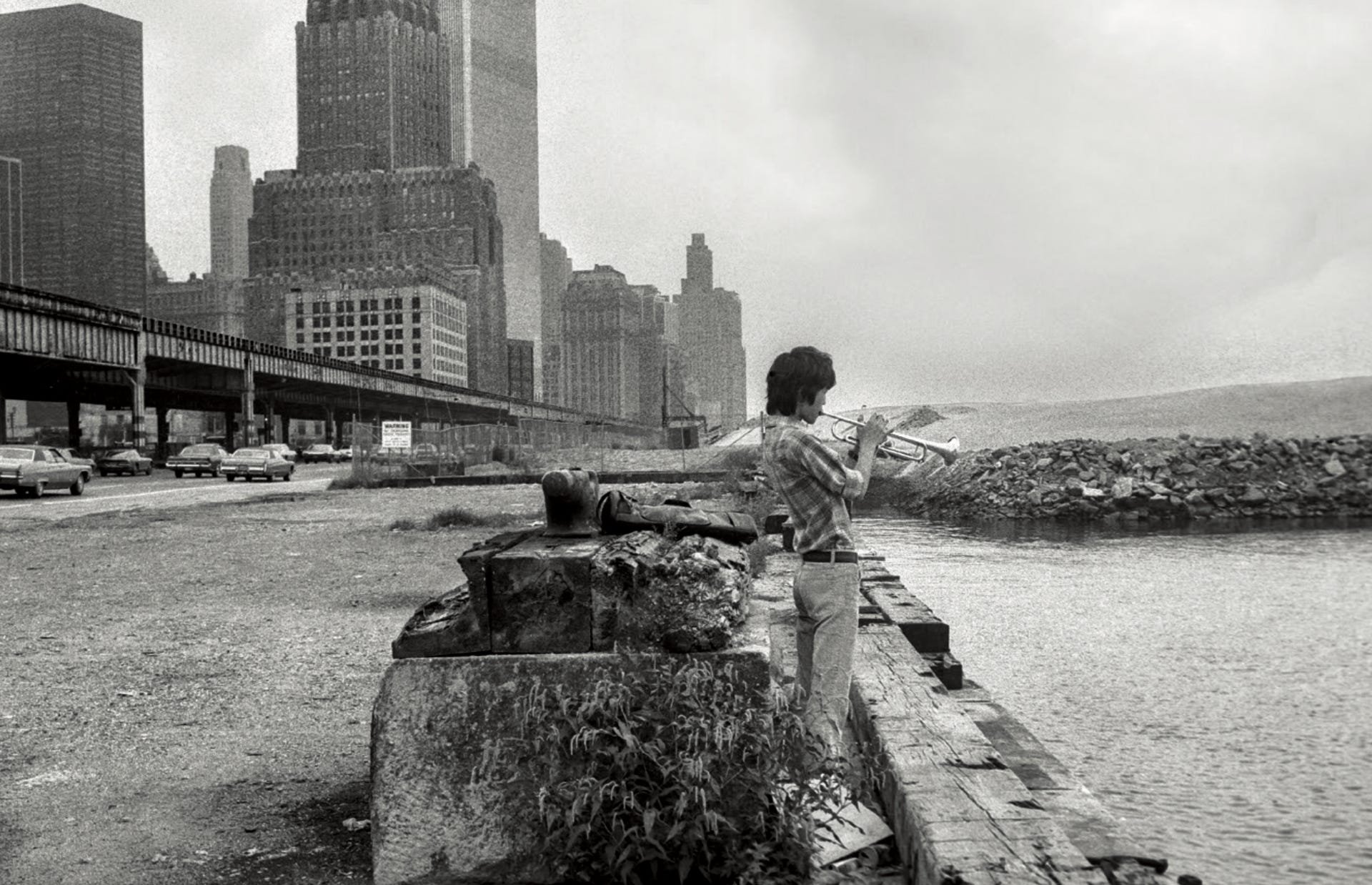

By the Hudson River, 1978. Photo: Martha Cooper

Thankfully no class, no economic system, no empire can rule for ever. The survivors of the working-class and those who demand justice and freedom for all have seen wealth come and they’ve seen wealth go. They’re the ones who’ll stick around, come what may, so the city will always be theirs in spirit. It won’t surprise them if at some point in the future capital retreats once again. Or if music returns to the streets.

La Fabrica, founded in Madrid in 1995, publishes books on photography, art and contemporary literature.

Guillermo M. Ferrando is a journalist, creative director and founder of Kind Projects, an independent studio that develops projects operating between culture, creativity and music as a universal language.

Tim Lawrence is the author of Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-1979, Hold on to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-91, and Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983. He is co-host of the Love Is the Message podcast as well as two parties, All Our Friendsand Lucky Cloud Sound System. He is a professor of Cultural Studies at the University of East London.