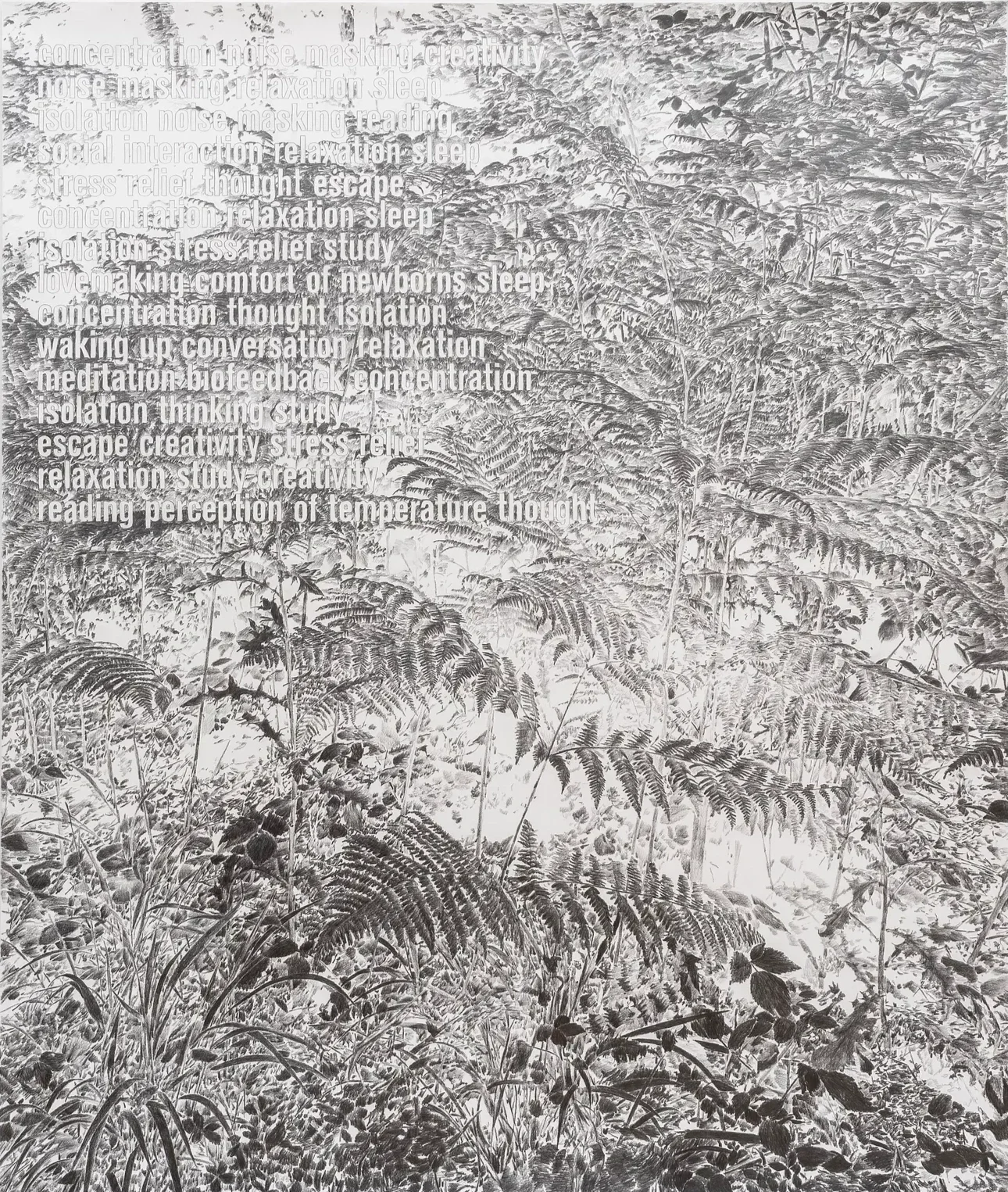

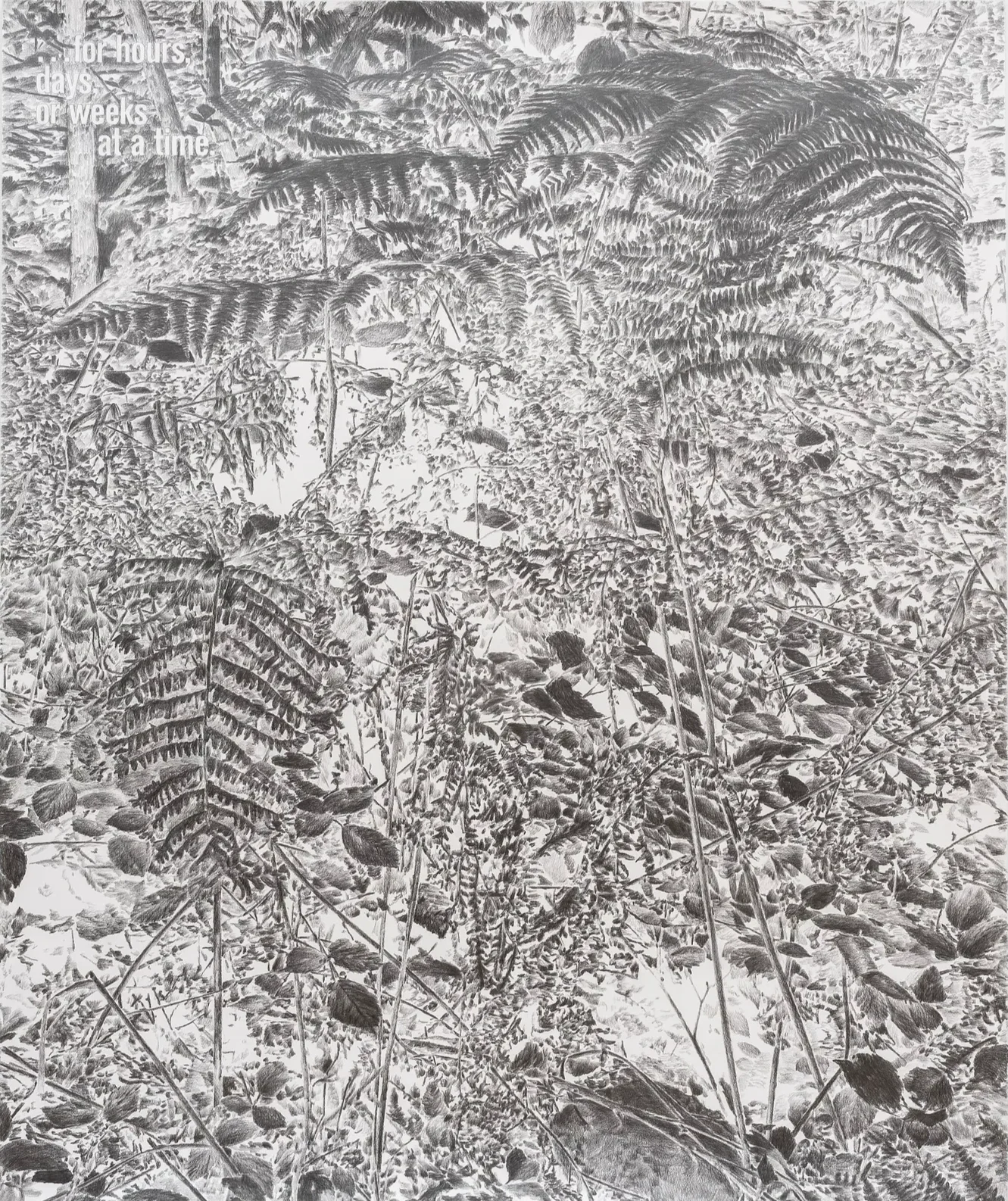

Martin Beck … for hours, days, or weeks at a time

1: Last Night, David Mancuso, counterculture, Martin’s art practice, hauntology and MoMA

Almost two years ago to the day I purchased an album titled environments 3, the third release in Irv Teibel’s environments series, released on Irv Teibel’s custom label, Syntonic Research, Inc. An artist based in New York and Vienna, Martin introduced me to the recordings, which formed one of the key elements of a new exhibition he was developing on the capturing, preserving and interpreting of environments. As soon as I eyed the album cover while listening for the first time I thought, “Martin is onto something here.”

Little did I know how far Martin would take it. The first iteration of the exhibition appeared as in place (environments) (2020), a 121-minute high-definition video that featured environmental shots taken in a shared home in Joshua Tree while selections from Teibel’s environments recordings played on a home stereo. Further elements appeared in a show that took place in Salzburger-Kunstverein in 2024, echo*, a collaboration between Martin and artist Sung Tieu, most notably a selection of Martin’s epic pencil drawings of ferns. Then came … for hours, days, or weeks at a time, the new, most developed articulation of the idea to date, which opened at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut on 30 March and runs through to 5 October. [1]

As I leafed through the … for hours… catalogue I immediately grasped that Martin had come up with something every bit as compelling as Last Night, his previous artwork series that appeared in multiple exhibitions. [2] It had been easy for me to become absorbed with Last Night. After all, the works revolved around a symbolic party hosted by David Mancuso at the Loft, a figure, party and in effect set of practices that I’ve devoted a significant portion of the last 28 years to narrating and supporting. Much more significantly, the cutting edge of the artistic journalistic ecosystem lauded the work. Artforum included an extended review of Last Night and the show in which it first appeared in full, rumours and murmurs, in its “best of” review of 2017. [3] In 2022 MoMA bought the most developed piece in the series and in 2024 arranged a wildly successful exhibition of Last Night. I wondered: how can Martin possibly follow this up? The … for hours… catalogue answered the question.

However it was only when I started to write this essay that I grasped that Last Night anticipated everything. One of its themes, after all, is that endings don’t amount to endings.

* * * * * * *

Last Night draws heavily on a rare, thirteen-and-a-half-hour recording of a Loft party, hosted by David Mancuso at the Loft on 99 Prince Street on 2 June 1984, the penultimate party he held at that location, half way through its 15th year. It’s the only such recording of its type because David didn’t like the idea of recording parties, or trying to capture them, and only a handful more would follow in the 2000s, none of them as expansive as by then the Loft had become a more circumscribed entity.

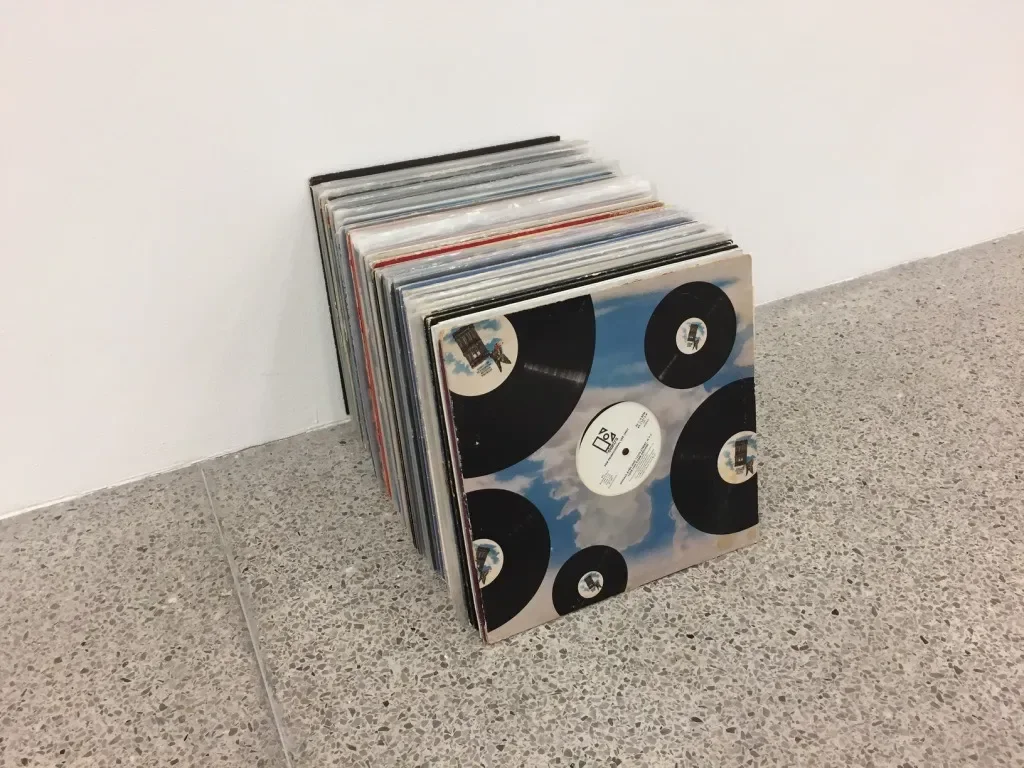

What would become a series of works first appeared as an art book published by White Columns in 2013. [4] After that Last Night manifested as a significantly more ambitious installation that featured a thirteen-and-a-half-hour film comprised of ten different close-up camera angles that captured the records playing in the same sequence as they’d appeared during the 1984 party. Martin teamed up with the independent filmmaker James Benning to carry out the filming. The video appears on a large screen and synched soundtrack that plays through an analogue stereo system that captures aspects of David’s own set-up. It generates a world that’s profoundly linked to the Loft but isn’t the Loft. Call it a Loft extension.

The last night video installation exhibited for the first time at the Kitchen, New York, in 2017. Dancers and art-gallery aficionados along with a relatively small intersection of visitors who were both entered the space, absorbed and experienced its information, and reminisced or asked questions or moved a little to the music. The book (along with errata) and the video installation then appeared alongside a Last Night picture/poem and vinyl installation at a major retrospective of Martin’s work held at Mumok, Austria’s largest modern art museum, in 2017. I travelled over to host a public conversation with Martin at the museum on Thursday 8 June.

Taking the opportunity to receive a guided tour of the exhibition from Martin before the evening talk, I was amazed. Up until now I’d only got to hold Last Night in my hands. Here I got to properly appreciate the depth and intentionality of his interest in and exploration of countercultural ideas and practices as well as similarly-minded articulations of alternative ways of living, even perception. Strikingly substantial, wide-ranging, sustained, precise and original, the exhibition presented an impressive body of rigorously conceptual work that combined a devotion to curation and exploration across a wide range of multimedia forms, often through surviving remnants of the culture or attempts to frame and even capture it. The collection expressed devotion and restraint, with Martin peering in, trying to observe or even somehow access the precipice of conjuncture as well as offer a roadmap for viewer-listeners to do the same.

Martin Beck, Last Night, exhibition at the Kitchen, New York City, 23-25 March 2017. Photo by Jason Mandellam, courtesy of the Kitchen.

* * * * * * *

Martin’s journey into counterculture might have began when he and his brother started to listen to 1960s rock music in the Austrian Alps in the mid-1970s. “Music has often been an entry point into the cultures that generated those sounds,” Martin noted in an interview with November conducted in July 2023. “Musical cultures frequently envision different worlds and ways of being; they imagine futures that challenge whatever the mainstream is at a particular time. Maybe that’s what triggered my interest.”[5] In the early 1990s Martin started to become “fascinated and bewildered by how countercultural moments and movements I was invested in started to get repackaged due to the availability of new technologies,” he added in one of several emails we exchanged while I was writing this piece.[6]

Martin suggests the example of DIY and punk’s cut-and-paste aesthetics. “They started to be digitally mimicked in slickly-produced, mass market magazines and typography, targeted at specific audiences,” he continued. “At the same time I also became fascinated with 1960s musical cultures being museum-ified, as when the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame opened in Cleveland, and the Hard Rock Cafe expanded and started to introduce displays of ephemera, especially in their Las Vegas venue.” In investigating these histories Martin is, he explained, “usually drawn to turning-point moments, to the paradoxes therein, where a single event, an artefact or a suite of artefacts, or a publishing trail open up possibilities for alternative futures but simultaneously haunt those possibilities.” He wants to explore how these historical moments are inevitably lost in time and can’t be recreated, yet certain artefacts carry traces of residual meaning that can help as we attempt to form our own imaginary relationship to the thing itself—a thing that was definitionally ephemeral. “I look for the paradoxes, openings that are closings that are openings,” he notes.

Martin explores the single event of the 1970 International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado, in The Environmental Witch-Hunt (2008), a 10-minute film that features six people walking through a forest in Aspen, Colorado, before they sit to stage a panel discussion. The exchange quotes from an essay French theorist Jean Baudrillard delivered to the conference that attacks its theme and the environmental movement’s complicity with state-generated environmental catastrophe. The film accompanies Panel 2—“Nothing better than a touch of ecology and catastrophe to unite the social classes . . .” (2008), an installation that combines original pieces with archival material plus a film that documents the conference. Martin explored the publishing trail of self-published newsletters and books about utopian rural communes of the 1960s in series of works titled Directions, Headlines, and Irritating Behaviors (2010),” examining how “a (non-photographic) image of a new social body was displayed in ephemeral manifestations and instructions.”[7] Martin’s 2012 book The Aspen Complex further explores what Artforumdescribes as “the intersection of culture and the ecological-industrial complex.”[8]

Still from Martin Beck, The Environmental Witch-Hunt, 2008. Sourced from Artforum

Martin found himself becoming particularly interested in the commodification of counterculture. “I often focused on the multiple meanings these processes generated,” he added. “On the one hand they gave access to important histories, on the other they obscured their formative contexts, which were often political and liberatory. I wanted to understand the contexts out of which these possible futures were created and learn from them, to learn how they came about and what of their constitutive forces still shape our present.”

In a 2015 interview Martin elaborated why the “somewhat paradoxical” character of the historical moments he turns to is significant. “Paradoxes point to possibilities and impossibilities,” he explained to with curator and writer Christina von Rotenhan. “The paradox is a figure capable of imaging multiple and complex ways of understanding history’s relation to the present; it can give form to the convergence of contradictory futures and multiple pasts embedded therein.”[9] Martin’s intent is to present the paradox, not to project his own interpretation of it or solve it on anyone’s behalf.

My contact with Martin began on 23 September 2014 via social media. What follows is a fairly detailed account of the ensuing exchange that followed, which centres around Martin’s first iteration of Last Night, an art book. While this material isn’t specific to … for hours… for me it was a formative conversation about an important contribution. I decided to indulge because I have a particular history with David and the Loft and can imagine that some readers will find the material interesting. Anyone who wants to read specifically about Martin’s new exhibition rather than this particular aspect of its background and the friendship that Martin and I began through the exchange around Last Night is encouraged to skip to the next section.

* * * * * * *

In that first message Martin wondered if I’d heard about his artist book, Last Night. He said there’d be a launch event at PS1 on the 27th where he and Matthew Higgs, the director of White Columns and publisher of the book, would select the full thirteen-and-a-half hours of music in the same sequence as that night at the Prince Street Loft on 2 June 1984. He offered to send me a book and hoped that we might meet. I thanked Martin but wasn’t quite sure what to make of it all, having become quite closely tied with David and his legacy during the course of 17 years.

My first interview with David in the spring of 1997 was sufficiently revelatory for me to go on to write Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970–1979, which positioned David as the era’s pioneering, visionary prophet.[10] During the course of the next 20 interviews conducted for that book David suggested I use the “Love Saves the Day” slogan associated with his inaugural Loft party in the title, which felt significant. Just before the book went into production, David also proposed that we co-host parties in London, which introduced a new dimension to our intertwinement.

A wider team gathered to stage the first event in June 2003, after which David started to travel to London four times a year, staying five days at a time. Within two years he’d persuaded us to take out a massive loan to purchase a sound system that resembled his set-up in New York. Ultimately David decided he only wanted to work with us in London plus Satoru Ogawa, the owner of Precious Hall in Sapporo and a born again David discipline, in Japan. This continued until a doctor advised him to stop travelling in late 2011. Along the way David sometimes asked me to help with aspects of his affairs as well as the safeguarding of his legacy.

So when Martin reached out I was mildly surprised that I hadn’t heard of his book and wondered how he’d worked things out with David, especially in terms of the launch event, which was marketed as being “part listening-session, part epic dance party”.[11]While David was dedicated to sharing good practice, he was also protective of the Loft, having long considered himself to be not the owner but the caretaker of the party. When folks hovered close, wanting to emulate his practice, his standard reply was: be original. I’m not suggesting for one moment that Last Night and the launch event weren’t original, just that Martin had entered a sphere where certain ways of being were unusually well established. Martin’s report that the PS1 event had gone “way beyond expectations” didn’t straightforwardly answer anything. But I’d soon grow to understand that Martin’s artistic practice is remarkably thoughtful, careful, intelligent, respectful and anti-egotistical. He is devoted to the prompt. I’d also go on to learn much from his prompting.

Martin’s book, I soon discovered, is entirely different, even the inverse, of Love Saves the Day. Instead of 500 pages of semi-novelistic drama combined with as much analysis as I could introduce within the narrative flow, Last Night listed all of the records selected at the penultimate Loft party at 99 Prince Street in 1984. Coincidentally, the list emerged in the first place through the broadcast of the tapes of the 2 June 1984 party in 2008 by Guillaume Chottin and Simon Halpin, two devotees of the London party, which, initially nameless, by assumed the name Lucky Cloud Sound System in 2005. David along with remixer and DJ François Kevorkian, who had organised the original recording, had wondered what to do with the tapes, if anything, for 24 years before David decided it would be appropriate to make them available to Guillaume Chottin and Simon Halpin to broadcast on their internet radio station, deepfrequency.com.

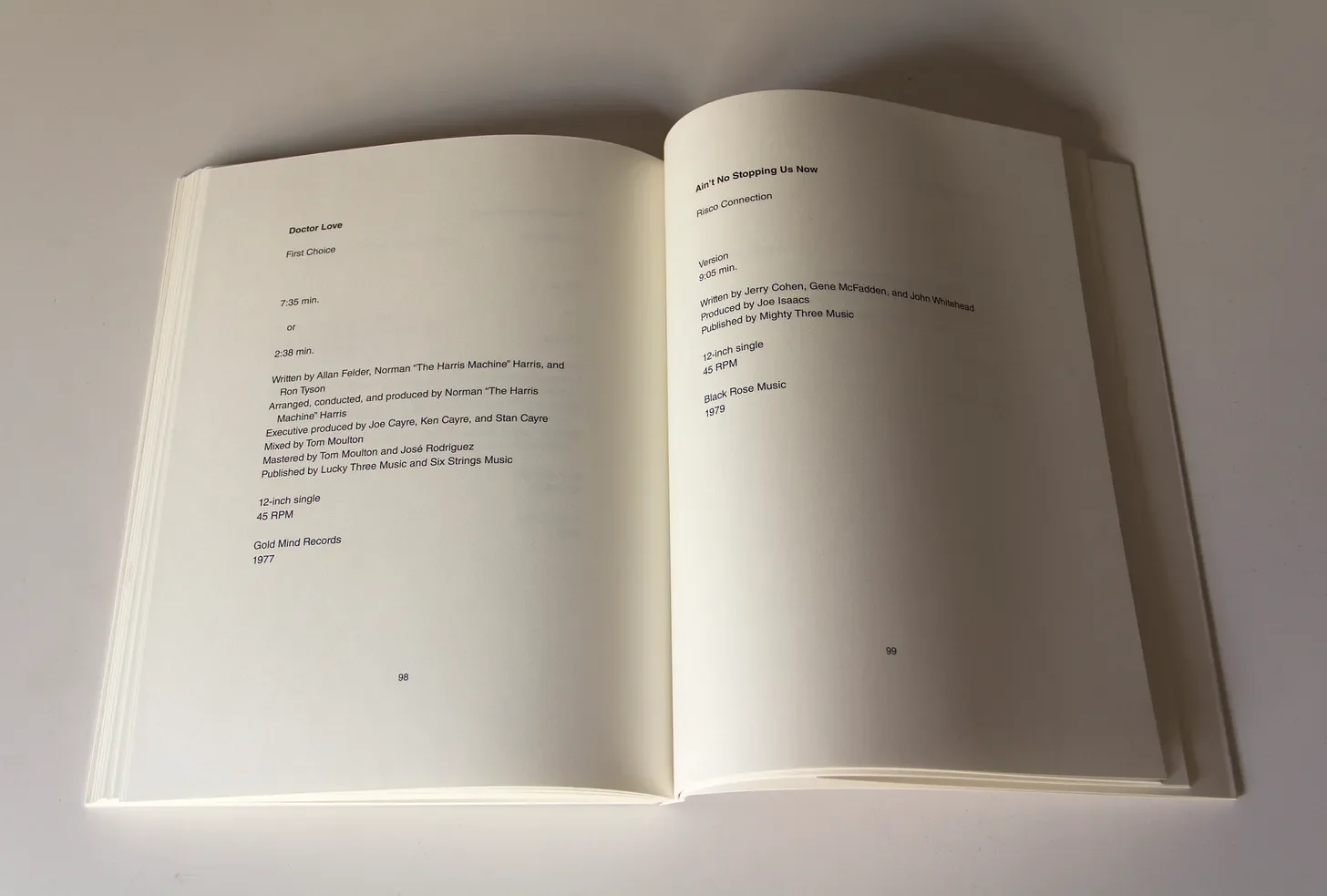

Incomplete annotations of the recording circulated before Martin created a thoroughly detailed, almost entirely accurate list that contained only one or two question marks against unknown selections plus full discographical information provided for each title. With one track listed per page, the typography was clean black and white. The narrative is the order of the titles. The analysis is intentionally minimalistic and rests on a handful of suggestive David quotes introduced at the front and back.

Martin’s point was to develop a laser focus on a rare relic of the culture, one that happened to fall four-and-a-half years after the closing point of Love Saves the Day. A complete statement in and of itself, there was nothing to add or subtract. In a way I was happy that it was so completely different to Love Saves the Day that there was, at least superficially, little if any overlap between the two books. I appreciated its elegance, its solidity, its attention to detail and its archiving of information related to a historic party.

Martin Beck, Last Night. New York: White Columns, 2013. Images courtesy of Martin Beck.

Last Night was also intentionally an artwork and I can’t say I initially understood or particularly appreciated how it operated. Staying in the comfort zone of my existing Love Saves the Day/Lucky Cloud Sound System/David knowledge, engagement and advocacy, I sent Martin a thank you email that outlined aspects of the book that left me unsure, and preferring to be direct rather than revert to pure congratulations, I put some questions to him.

Could the minimalistic text capture the vibrant energy of the Loft? What were the implications of attributing the musical selections of 2 June 1984 to David when David rejected the individual model of creativity, believing that the dancing crowd co-authored any musical journey, plus David went to extensive length to remain anonymous at the parties? Didn’t the book itself also replicate a version of artistic authorship that David rejected, which included his belief that the party was collectively owned? Was the Last Night title appropriate given that David had refused to reference the 2 June 1984 party—which turned out to be the penultimate party at the Prince Street Loft—as being the “last”, preferring to see it as the precursor to a rebirth that would soon materialise at his Third Street location?

Martin replied:

“I am a visual artist, often working with historical subject matter and with a keen interest in the tension between representability of histories within the languages of art. That is to say that my work’s ambition goes toward imaging through working with structures.

Of course, one could narrate that particular night in very different ways, from oral histories to narrative descriptions, to more academic approaches; or even with the few photos that exist. But from my artistic perspective it seemed more pertinent to let the songs’s rhetoric and the information about them tell the spirit of the event. I believe the titles alone, their production information, and their sequences speak very strongly (try reading just the titles in sequence and see what unfolds); they are a story but they are not the party and they do not represent the party—how could they? It would be presumptuous to think they could.

I’ve sometimes thought of the book as an epic poem; one that is typeset at a certain scale on document-sized pages with plenty of blank space to project into, with typographic restraint to let the language come forward. To me these and other small decisions are important visual tools. I recognize that not everyone shares them. There are many visual worlds, desires, and preferences; I see that and can respect it.

For me, it is exactly the ‘minimalism’ of the book that resists that presumption, the dry typography, the scale of the book as it creates space to project into. This restraint is an important visual and methodical device; the production details of the music’s selection and their sequence in their most stripped down form is, to me, a way to point to the poetry that I understand David’s music playing as being.

I believe strongly that there is a strength in abstraction, a tension that arises between restraint and the emotional power and exuberance of the songs’ rhetoric. That tension, or maybe better: that paradox, to me, is one of the forces that makes for a successful artwork; especially when engaging with historical subject matter. I see it as a methodological foundation of generating expression within a certain kind of art practice. Maybe it’s not everyone’s cup of the tea, but art practice and discourse operate within and use different logics than historiography, ethnography, sociology, documentarism, etc.

I understand that, from the background of all your work on dance culture and specifically on the Loft, my book might seem inadequate but I nevertheless feel strongly about it being a positive contribution. Not an academic one, but an artistic one. To me, the book and the list, as I wrote in a lecture a while ago, “builds a paradoxical bridge between structure and desire, between abstraction and affect, between form and the social. The list is ... an unstable diagram that points to an image between images. A document as an absence.”

Maybe these thoughts help understand where I am coming from. Despite our different take on these and other things I do believe we share a lot in our passion for the music and the contexts that bring it forward. And I look forward to experience that shared passion in a person-to-person conversation.

I admired Martin ability to explain and stand by his intentions in a non-defensive way while holding out the hand of friendship. I acknowledged that in many respects I was ventriloquising a series of ideas David had put to me over time. David was extremely particular about language and framing, especially when it came to the Loft. This had extended to London, where, I wrote, he “wouldn’t let us describe the parties we put on with him in London as the Loft or the Loft in London, even though we modelled the party on just about everything that took place in New York.” I’d learned a great deal from David and had become an advocate, yet I’d already learned a great deal from Martin.

The exchange with Martin encouraged me to reflect on how I’d been quick to step into the role of gatekeeper. David had expressed appreciation of my writing and my contribution to Lucky Cloud Sound System, and on occasion had even asked me to intervene in matters that revolved around turf or maybe understanding. I also didn’t exactly need to be persuaded to repeat “what David thought” about a whole range of matters. Yet David and I didn’t always agree, i.e. we could tussle, often energetically, and I’d also become aware how other gatekeepers could leverage their position in ways that could be consciously or unconsciously self-interested. Who was to say I wasn’t doing the same? Ultimately there was and never could be a singular knowledge or truth about the Loft, which shifted over time and was always communal and therefore pluralistic.”

I wrote another email and along the way mentioned:

“I’m not for a moment suggesting anything about how David would respond to the book. We haven’t spoken for a few months now and for all I know David hasn’t tracked its journey. It’s possible he will find the book entirely positive and uplifting. Maybe this doesn’t even matter because as David himself acknowledges, the Loft is bigger than him.”

I added:

“I appreciate that my response has been somewhat knee-jerk inasmuch as I’ve thrown out immediate thoughts instead of sitting on the book for a few months and working out how it registers then. I might well grow to regret saying all of the above and take a completely different line.”

I suggested Martin might try to speak with David about these matters and signed off saying that I looked forward to “meeting and sharing our mutual enthusiasm, hopefully on the dance floor as well as over coffee.

The email tussle melted instantaneously when Martin and I met for the first time in London in January 2016. Five months later he returned for a Lucky Cloud Sound System party; we hung out and he also helped set up as well as dance the evening away. We continued to talk, especially in the run-up to the Mumok conversation of June 2017, even more during the two days I stayed in Vienna, and more and more when I went to stay with Martin in the “simple house” in Joshua Tree he shares with Julie Ault, with whom he has collaborated closely for decades, for 10 days that August, where we mixed hiking, reading, writing, listening to music and cooking with conversation. Each step of the way I learned more about Martin’s journey into Last Night.

* * * * * * *

Martin first came across the Loft in the second half of the nineties via the East Village record store Dance Tracks, which was selling 12”s from the Loft Classics bootleg releases. “I had no idea what the Loft was back then, I just liked the tunes,” he remembers. Coincidentally during the same period I was heading to the store every Friday night and have a hazy memory of David reprimanding me for purchasing from the series.

Martin bought Love Saves the Day soon after it came out, “started to understand what the Loft was/is” and began to collect Loft music, first in digital format, then on vinyl, especially after piecing together sections of the deepfrequency.com broadcast. For a period this amounted to “a private passion discrete from my art practice.”[12] Then, in late 2011, he combined the two after concluding that the records played at the Loft resembled the kind of “documentary remains” he liked to turn to in his practice.[13] Martin explained:

“For a while I was under the impression the Loft was all in past tense. I was trying to figure out how I could capture something from it. What is left that is tangible? What can it communicate? By playing the records in sequence I wanted to understand, what might have been this thing that people are talking about? There was this tension between something that was tangible and intangible.”

Come the summer of 2013 Martin had purchased a copy of every record selected at the 2 June 1984 party save for two mystery songs. Many years later I got to see the spreadsheet Martin had created to chart all the purchases; the level of detail, ordering and annotation, the incredible amount of work and care he’d put into the activity, moved me to suggest it amounted to an artwork in itself! By the end of 2013 the book was ready and around the same time Martin met dancer, artist, art installer and music aficionado Gary Murphy while installing Macho Man: Tell It To My Heart, an exhibition at Artists Space in New York composed of artworks from the collection of Julie Ault.[14] They talked about Love Saves the Day, Martin showed him a copy of Last Night on his laptop, Gary offered to take him to the next party as a guest; the Valentine’s Day gathering of February 2014.

By this point David had stopped attending the Loft, having pulled back from musical hosting around the same time he stopped travelling to Japan and London. Even before then, around 2008, David had started to ask long-time Loft devotee and stand-in musical host Douglas Sherman to put the records he selected onto the party’s turntables because the tone arms were equipped with highly sensitive Koetsu cartridges, because his sight was weakening and his hands were shaky. He also started to leave the party early, handing over to Douglas. Yet he never stopped hosting the parties. He just grew to prefer to carry out this role, his life mission, from his tiny, fifth floor walk-up apartment on Avenue C (part of a community housing initiative he’d landed via longstanding volunteer community work he was conducting for the association).

The inevitability that Martin didn’t get to witness David work as musical host did nothing to detract from the experience. Whatever had been coded into the 2 June 1984 playlist remained a vibrant, living, multidimensional entity that exceeded the sum of its parts as well as expectations and rationalisations. A series of ordered records collected via Discogs transmuted into an immersive, unfolding experience. The wonder and joy of the party even filled Martin with a new sense of purpose. “By going to the parties and getting to know people there, I became aware of a few misidentified versions of songs and started to publish errata documents to the book,” adds Martin.

What amounted to an epiphany was, I imagine, rooted in Martin experiencing for one of the very first times—even maybe the very first time—an expression of the thing that was fundamental to counterculture. Up to that point his experience of countercultural expression was rooted in objects and mediation. “In my larger practice I’m interested in what I call the structure of community, what can be understood as a structural force, what togetherness forms,” he told me. “Whether it’s a dance party like the Loft or a commune from the 1960s or 1970s, I ask: what are the rituals, what are the rules, how do you live, what do you do when you have a conflict, how are these things negotiated? I try to understand such things in a deeper sense, not simply as images of hippies in the pastures or people dancing. I’m interested in the structural underpinnings, the workings beyond the clichés, something more fundamental.” On the Loft floor he experienced the structural underpinnings firsthand.

During the period of making the book Martin reached out to David and they spoke on the phone a few times. They also arranged to meet on a couple of occasions but David didn’t show up. In the end Martin met David on the couple of occasions he sat at the front door of the Loft, having otherwise stopped going to the party altogether, “but David didn’t seem to be interested in talking about the book or the 2 June 1984 party,” recalls Martin.

A little later, Martin heard that David had described the book as a “sophisticated bootleg”, the memory of which prompted a warm, little laugh as Martin recounted the story to me. For me the laugh captured Martin’s admiration for David’s way with words, an appreciation of the value of David’s deep commitment to protecting the rights of an original artist (which had led him to refuse to play bootlegs), the understanding that in this case there was no artistic intellectual property to protect and a familiarity with having to deal with folks who didn’t quite get it. At least Last Night wasn’t a regular bootleg, it was a sophisticated one!

As it happens—and David had no particular reason to appreciate this—Last Night didn’t amount to a commercial art initiative, never mind a commercial “bootleg” (Martin being the creator of work that can be challenging for conventional art collectors). It was an unconventional work that was no less valid for its unorthodoxy. Instead of playing at full volume it quietly prompted subtle, perception-opening questions. In other words, Martin was doing what artists do: he looked around, sought out inspiration, considered aspects of experiencing and then created something. Rather than encroaching on something, Martin was moved by his fascination with the Loft to make an offering. Nor did David issue an instruction to cease and desist. That wasn’t David’s way and he lived a happier life for it.

Along the way I learned that the 2 June 1984 party at Prince Street was the penultimate party at the Loft, but this hardly mattered because Last Night was never meant to literally refer to the “last party” at that location. “The phrase contains a complex range of connotations,” he told Christina von Rotenhan in an interview published in 2015 in Martin Beck: summer winter east west. “It can refer to an emotionally coded moment in the immediate past or, simply, to the marking of time—or anything in between.” He noted that “its associations range from an ecstatic night of dancing to an end of an era: pleasure at a crossroads” before adding that the phrase can also “be read in a more abstract way: as a poetic device that connects structure, time, and affect; as a linguistic connector joint that unlocks new spaces in the midst of the paradoxes that often define the relationship between memory and historicity.” Rounding things off, Martin observed that “‘Last night’ stands for ending but also for beginning.”[15] Drawn to the Derridean concept of “hauntology” as well as Mark Fisher’s more recent writings on the idea, Martin maintains that Last Night references possible alternative futures that are nevertheless haunted by the past, or that we are haunted by futures that failed to happen.[16]

Many within the wider Loft community would go on to embrace Last Nightwith huge enthusiasm—and as David believed it was the community that embodied the party, with the party a voluntary association that could never be owned. The first big hug unfolded in the form of a party that almost surprised itself at the PS1 book launch of September 2014. A second followed when Martin exhibited the video installation iteration of Last Night at the Kitchen in March 2016. Like a good party, the underlying idea for the artwork was worth returning to and doing again, only differently, it transpired. Also like a good party—and I’d be surprised if this didn’t apply to the Loft, as hallowed as the inaugural night of 14 February 1970 has become—its first articulation wasn’t necessarily its fullest, even if a semblance of its potential had been partly imagined from the get-go.

The Loft on Second Avenue at the end of set-up, August 2014. Photographer unknown.

* * * * * * *

Martin’s initial idea for Last Night was to create a video installation but it didn’t take him long to conclude that “nobody other than myself would be interested in looking at records spinning for thirteen hours.” So he ran with the book instead and then headed to Joshua Tree to spend the summer of 2014 with his good friend James Benning, a film maker and a legend in the field of experimental cinema. When Martin got around to explaining why he’d decided against making a film James told him he was “crazy” and offered to do the camera for him. Everything unfolded from there. As Martin told me:

“Later that year I began putting together the record player using classic analogue stereo equipment that wasn’t as high-end as the Loft set-up but was rooted in similar era and intent. I purchased a Thorens 125 MK II turntable, an SME Series II tone arm and I also found this moving coil cartridge in mint condition from the early 1980s called Sleeping Beauty. It looks beautiful and sounds great. I went through the process of educating myself about the sound equipment as I put all these elements together, so it was like real time.

Filming happened in the summer of 2015. We filmed every day for 6-7 hours. Some records we had to shoot multiple times because something would go wrong. It took us three weeks. It was like this collaborative project and I even offered to credit James as a co-author. He didn't want that and said, “It’s your idea, I’ve been happy to help.”

It took about eight months to edit—not every day. It turned out that commercial editing software isn’t built to make a thirteen-hour film. I worked with an editor in New York and we ran into one technical problem after another. The editor built a computer just to render the film. The film was finished in early 2016 and premiered at the Kitchen.”

At some point I asked Martin if he’d sat through the full thirteen-and-a-half hours in one go. “With bathroom breaks, yes,” he replied.

After screening in several cities, including an event Martin and I organised at the Red Gallery in London in June 2018, MoMA purchased Last Night in 2022 and on 2 June 2024 exhibited the work to mark the 40th anniversary of the party it references. That day the museum arranged for the opening hours to be specially extended from late morning to around 1:00am—at least in the exhibition room—so that it could run the full thirteen-and-a-half hours. The day and evening remains the most engaging and emotive art gallery experience I’ve ever had. I’ve been to a decent number of stunning shows. It’s just that 2 June reached an entirely different artistic and socially-expressive level. The polite yet hearty MoMA takeover also amounted to a moment of celebration for Martin, for David and also the historic and ongoing Loft community. The MoMA website even published an oral history of the party by curator May Makki that featured several longstanding contributor-protectors, Ernesto Green, Sandy Moon, Douglas Sherman, Edowa Shimizu, Luis Vargas.[17]

Martin Beck, Last Night, MoMA exhibition, 2 June 2024. Photo by author.

The one-day exhibition didn’t amount to a party as such; Martin was always careful to note that Last Night is an artwork, not a party. Nevertheless the organisation of the room—including the installation of a Loft-based sound system (by Douglas and co-Loft stalwarts Edowa Shimizu and Luis Vargas) featuring Mark Levinson amplifiers and four Klipschorn loudspeakers, a 20 feet wide x 11 feet tall screen.

The introduction of sofas and cushions, along with a generous supply of refreshments led the marathon exhibition-event to became a slowly-unfolding repository of memories and meetings, re-lived recordings and newly-absorbed moving images. Even James Benning, having travelled over from California, told Martin that thanks to the size of the screen he observed all manner of new micro-details in the film he hadn’t noticed before. Amidst all of the interactions, reunions and introductions that took place in that multigenerational, multi-experiential room, the emotional, conversational and physical exchanges almost imperceptibly led more and more attendees to begin to sway and then dance. I don’t think the MoMA team, whose commitment to hosting the day according to Martin’s wishes was unswerving, could believe the feeling that emerged in the room.

Audience at the artist talk with Martin Beck, chaired by May Makki, 1 June 2024. James Benning sits on the sofa, left. Photo by author.

During the screening of Last Night, MoMA, 2 June 2024. Photo by author.

The euphoric applause that followed at the end of the film expressed shared appreciation of the epic journey of the screening while connecting everyone in the room to the culture of the Loft as expressed through a mediated exploration of a historic party that took place 40 years ago that day. That mediation had become a way for those who gathered, many of them Loft dancers to deepen their engagement with the Loft. As they did so they connected with previous generations, a significant number of whom showed up, and future ones, with recently-introduced enthusiasts a glowing presence. Martin drew inspiration from the Loft to create Last Night and through the screening gave back to the Loft. And now, remarkably, an articulation of the Loft, without question the longest-running community party in New York City’s history, had been welcomed into and given a home in New York’s most prestigious modern art museum.

Last Night at MoMA became the first of an infinite number of new nights.

2: Irv Teibel, environments, eco-consciousness, counterculture, “Ultimate Thunderstorm” and David Mancuso

By the time MoMA exhibited the video installation Last Night on 2 June 2024 Martin’s work on his next exhibition, … for hours, days, or weeks at a time, was already well advanced. He’d resolved to explore the “methods and means through which environments are captured, compressed, and represented.”[18] For his lift-off material he turned to the environmental recordings plus accompanying artwork, literature and marketing paraphernalia of Irv Teibel and his pioneering, digitally-processed field recordings of the late 1960s and 1970s, released on Syntonic Research, Inc.

Teibel was a new figure for me, even if it would turn out I was indirectly aware of his work (of which more soon). He remains a fascinating and possibly under-appreciated figure whose pioneering environmental field recordings include “The Psychologically Ultimate Seashore”, “Optimum Aviary”, “Dawn At New Hope Pennsylvania (June, 1969)”, “Dusk At New Hope, Pennsylvania”, “Ultimate Thunderstorm”, “Gentle Rain in a Pine Forest”, “Wind In The Trees”, “Dawn In The Okefenokee Swamp”, “Dusk In The Okefenokee Swamp”, “Summer Cornfield” and so on.[19] In combination with their album artwork and sleeve notes, all created by Teibel, who had a background in graphic design and photojournalism, the recordings reconfigured the human experience of the natural environment. In retrospect they also offer a way into understanding how Teibel and his listeners sought to reinvent the human experience, a central concern of the 1960s countercultural movement.

Teibel ventured into environmental sound in 1968 when he recorded the ocean at Brighton Beach, Coney Island, for Tony Conrad’s underground film Coming Attractions. Conrad had already worked in La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music before he protested against Young’s growing embrace of composition and the elitism of New York’s art institutions, and performed with Lou Reed in a Primitives recording session that featured sculptor and environmental art pioneer Walter De Maria on percussion. De Maria’s unreleased recordings “Cricket Music” (1963) and “Ocean Music” (1968), which combined drums with environmental field recordings, inspired Conrad and Teibel to record the ocean at Brighton Beach. Teibel carried out the work using an Uher stereo reel-to-reel tape recorder yet questioned the veracity of the result.

Soon after Teibel played chess with a friend who worked in psychoacoustics and learned that a nineteenth century German scientist called Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz had theorised that natural sounds could produce psychological benefits if they were reproduced accurately. The encounter provided Teibel with a sense of purpose. He would record environmental sounds as a novel form of self-help that would enable individuals to function more effectively. Students could study more effectively, insomniacs could sleep better, writers could become more expressive, corporate executives could manage more effectively. Nature was a resource that could serve humanity.

The basic challenge of how to record nature effectively remained. Using a microphone and tape, and always battling with distortion, Teibel found it hard to record anything that sounded like the thing itself. He reasoned:

“The first problem is that the sounds of nature are not merely a specific set of frequencies, such as the human voice or a particular musical instrument, but are often a form of ‘noise’ that contains hundreds if not thousands of specific frequencies, all of which contribute to the makeup of the particular sound. The second problem is that of reference: hardly anyone has heard Mick Jagger without a microphone, but almost everyone has heard a rainstorm or the sibilant expiration of an ocean wave and knows what the real sound should be.”[20]

A year later he had “produced a hundred stereo recordings not one of which actually sounded, to my mind’s ear, like the ocean I wanted to hear.”[21]

A friend who worked in the nascent computer industry showed more enthusiasm for the recordings and suggested that Teibel digitise his recordings, something that had never been tried before. They started with a segment from the Brighton Beach tape that lasted for a few minutes, which was all the program they were using could handle. The initial results were disappointing. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, the speakers started to emit “a beautiful, tranquil ocean sound I had never heard before”, he recalled.[22] Even the splice “could not be detected, as an electronic random noise generator reprogrammed the waveform parameters with each cycle and created subtle new waves that never repeated. By adjusting bandwidth constraints, we got the sound to grow more and more realistic until what we heard was a serenely majestic ocean sound complete with bubbling surf and a faintly perceived, eerily synthesised foghorn.”[23]

Various other adjustments and tests followed until Teibel felt he had conquered the challenges of technology as well as nature. The act of processing that enable Teibel to render the captivating sound of the natural environment he’d been unable to capture in a singular, original recording. “He treated magnetic tapes as a medium, the way that a painter would treat watercolour or oil paint,” said Jessica Wood, an assistant curator of the Music and Recorded Sound Division at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, commented in 2019. “He liberated recorded sound from just being secondary to whatever it was recording and elevated recorded sound to being an art form in and of itself.”[24]

Teibel could have decided to release his highly edited and processed version of the original Brighton Beach recording and let it speak for itself. Instead he decided to explore if it might produce certain benefits that could enhance its value to listeners and therefore add to its commercial viability. He set about doing this by asking a psychology professor based in Long Island to test-run the tape with graduates, suggesting they use it as an aid to concentration and relaxation. The students who listened at night reported that their dreams had become more vivid and they woke up feeling unusually refreshed. Daytime listening resulted in improved comprehension and reading. Some of the students didn’t even want to hand the tapes back.

The liner notes printed on the sleeve of Environments Disc One, which features “The Psychologically Ultimate Seashore” on side one and “Optimum Aviary” on side two, describe at some length how the record should be played as well as the benefits that can accrue:

“In listening tests conducted prior to the release of ENVIRONMENTS ONE, it was found that this sort of sound had a direct effect on the imagination and subconscious of the listener, no matter what his age or occupation. If used while reading, comprehension and reading speed improve noticeably. If used at mealtime, appetites improve. Insomniacs fall asleep without the aid of drugs. Hypertension vanishes. Student’s marks improve. Its effect on the aesthetics of lovemaking is truly remarkable. In noisy or very quiet surroundings, improvement in working conditions is little short of miraculous. Teenagers are the records’ biggest fans; they call it everything from ‘the ultimate trip’ to ‘sensual rock’.”[25]

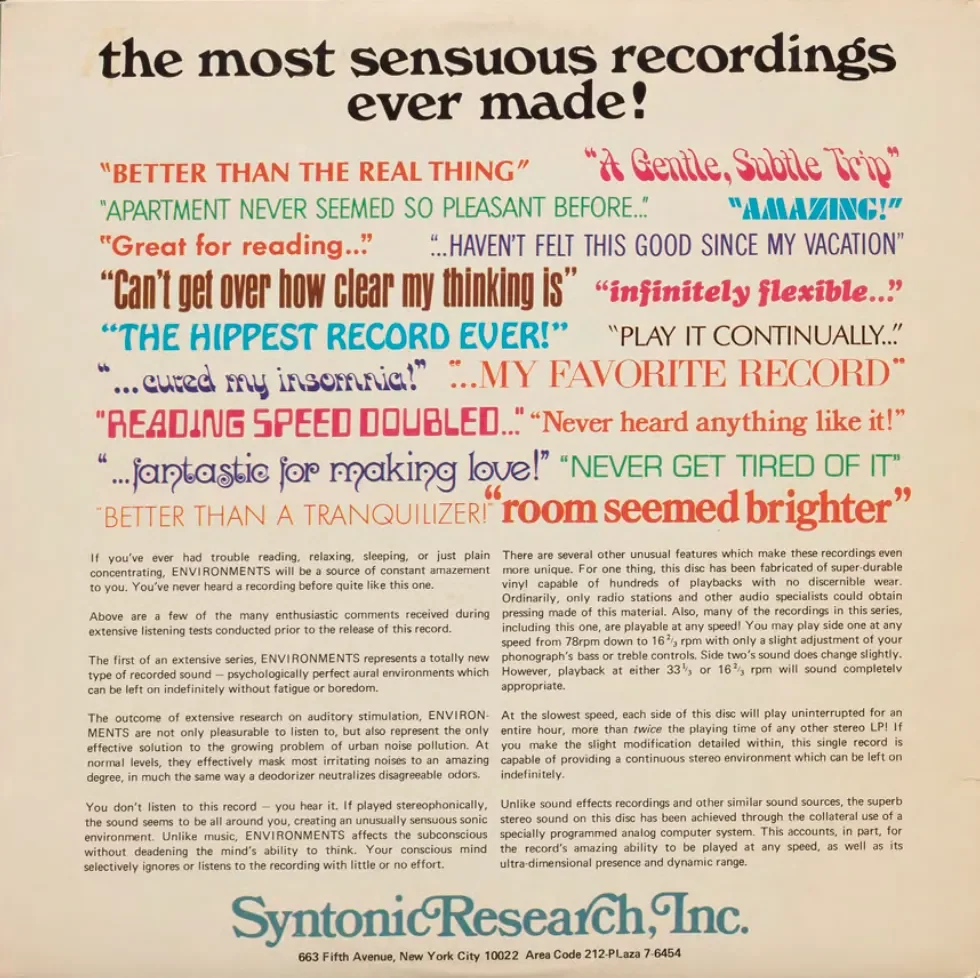

The back cover develops the sales pitch. It re-emphasises the recording’s ability to help with reading, relaxing, sleeping and concentrating. It presents a series of listener-testimonies presented in a range of fonts and colours. It offers practical advice on how to maximise the benefits: the record should be played at normal levels or lower; it should be heard instead of listened to; and its speed could be adjusted to affect your heartbeat, metabolism and respiration. “Articles appeared in Newsweek and the New York Times, comparing the record's effects to those of soma, Aldous Huxley's imaginary drug described in Brave New World,” Teibel recounted of the record’s release. “My obsession had become reality and a new form of recorded sound had been born via computer. I sold the rights to Environments Disc One to Atlantic Records and retired for a while. Mother nature had been digitalised.”[26]

Back cover of Environments Disc One (Syntonic Research, Inc., 1969).

Collaborating with a biologist based at Columbia University and a former Bell Laboratories researcher who now taught psychoacoustics at CCNY (City College of the City University of New York), Teibel drew on biofeedback analysis to test bodily impact of his recordings on brain waves, blood pressure, respiration, and so on. The aim was to help “hearers” achieve a brain wave pattern of 9 to 12 cycles per second, or a relaxed, peaceful, or floating state known as the alpha state. “We're trying,” Teibel noted in a 1975 interview, “to help people go into alpha state without knowing what they’re doing.”[27] Teibel’s level of intentionality is something to behold, perhaps even unprecedented, and would permeate his entire catalogue, which concluded with the release of environments 11 in 1979.

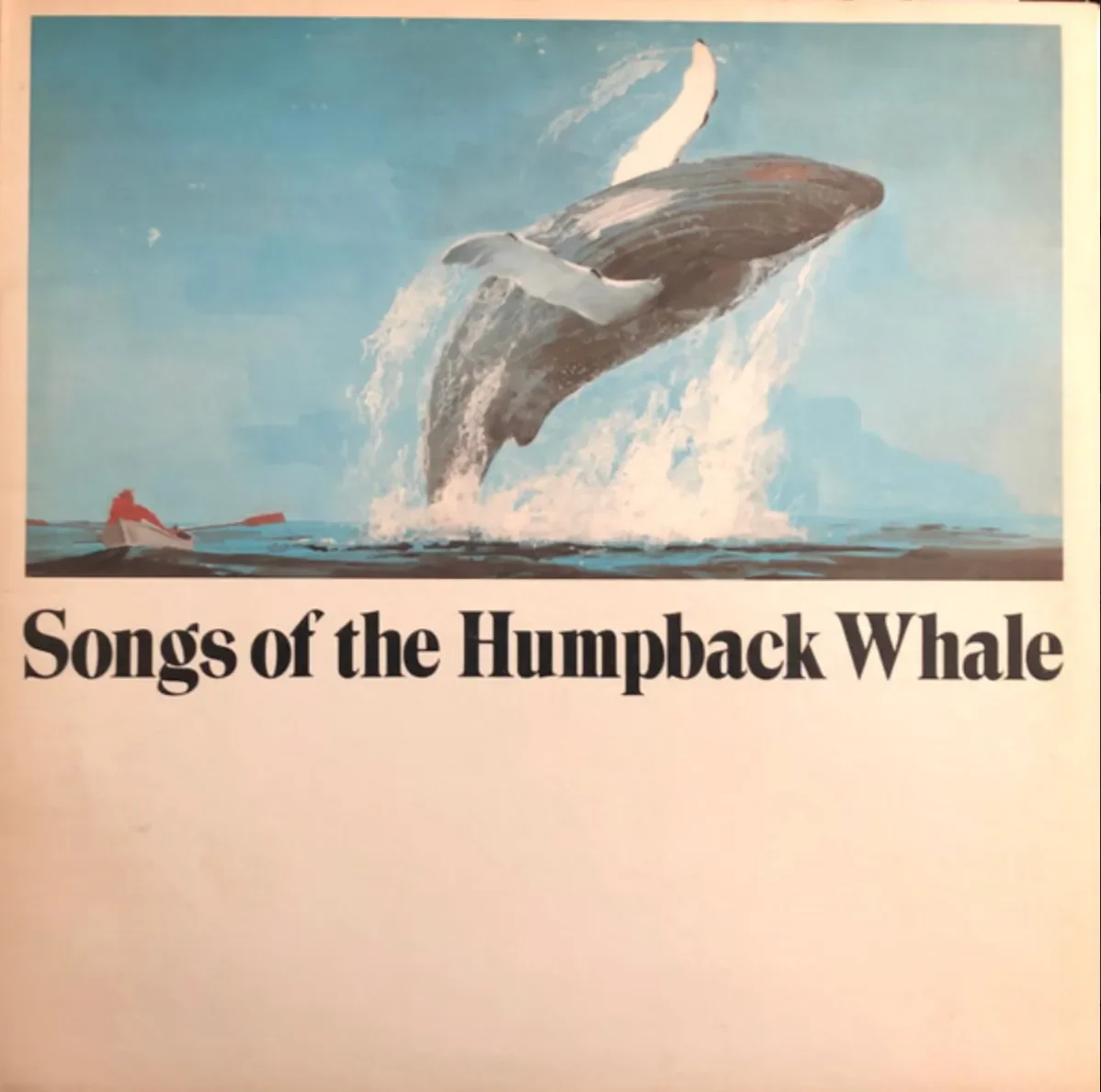

Teibel’s focus on benefits indicates that he was out-of-synch with the wider rise in eco-consciousness. During the 1960s awareness of the damage corporations and governments were inflicting on the environment along with the fragility of the planetary ecosystem and the threat of the nuclear arms race increased exponentially. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at any Speed (1965) and Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968) punctuated the shift. A 1969 UNESCO conference in San Francesco ratified a proposal that led to the introduction of the first Earth Day in March 1970. Biologist Roger Payne’s 1970 recording, Songs of the Humpback Whale contributed to the tide.[28] Greenpeace formed as Don’t Make a Wave in Vancouver in 1969 before adopting their enduring name in 1971.

Teibel showed no direct concern with the wellbeing of the natural environment in the written material that accompanied his releases nor in interviews. On the contrary, he was a humancentric utilitarian. “A good deal of the progress of civilisation over the centuries has been a function of gaining control over natural processes so they can be used when we need them,” he noted in an article published c. 1970-71.[29] “I did not see anything that would indicate a clear connection between Teibel and the environmental movement,” Martin confirmed in an exchange with me. “The archive doesn’t have anything to support that. Earth Day was only instituted in 1970 and the movement took off from there. Teibel was an entrepreneur with experience in marketing, photography, graphic design and just a little sound recording.” Martin added: “He was keen on developing a business from the ocean recording.”

As we’ve become evermore conscious of humanity’s direct contribution to a climate emergency largely generated by the northern hemisphere, it’s become easier to conclude that, as Mike Powell maintains in a far-reaching and thoughtful article published in Pitchfork in 2016, Teibel “was no environmentalist.” Powell continues:

“If anything, nature was his obstacle, the raw material out of which he had to sculpt something more appealing. Reflecting on recordings made in Florida’s Okefenokee Swamp, one of the most unspoiled places in the country, Teibel said the bugs bothered him, the frequencies were hard to work with, and his schnauzer, Max, was harassed by alligators. As for the great symphony of night, Teibel slept with earplugs in.”

Powell adds:

“Behind Environments’ hippyish premise—that we are biologically wired to thrive on the heartbeat of the earth—were coarser, more modern notions. By Teibel’s own admission, the series had been conceived not as a way to reconnect with the world but to shut it out. Everything about its packaging and presentation was haunted by the task of coping: of stabilising in unstable situations, of squeaking through until the next day.”[30]

Comparing Teibel to Payne’s recording of whales, Powell concludes:

“Teibel, a fast-talking cosmopolitan who probably could’ve sold water to a river in a rainstorm, didn’t seem half as concerned about what we could do for the whales as what the whales could do for us.”[31]

Having not immediately considered Teibel’s responsibility to the protection of the natural environment, I initially drew the moral I wanted to draw from Powell’s article. Surely someone who’d pioneered a series of recordings titled environments should’ve been tuned into the emergent, countercultural, counter-hegemonic way of thinking outlined by Carson et al. The sleeve notes to Songs of the Humpback Whale outlined what was possible. With a background in biological acoustics, Payne had already decided to turn his attention to whales when he heard a local radio station announce that a dead whale had washed ashore on Revere Beach, close to Tuffs University, Boston, where he worked. On arriving Payne saw that a number of people had mutilated the whale, cutting off the lobes of its tail, carving initials onto its skin, and sticking a cigar butt into its blowhole. Payne removed the butt and resolved to learn enough about whales to have “some effect on their fate”. Later that year he delivered a testimony to the US Department of the Interior, arguing for great whales to be listed as an endangered species.[32] I started to fantasise, couldn’t Teibel have been just a bit more like Payne?

Front cover, Songs of the Humpback Whale (Capitol, 1970).

At the same time I couldn’t quite reconcile myself to the idea that Teibel spent almost certainly thousands of hours in nature, recording sound. How could he have experienced it as a hostile element he not only didn’t care for but actively wanted to shut out? A review of Teibel’s activity slowly revealed fragments of information that offered a sketch of someone who was indeed appreciative of the natural environment, even if, having grown up in Buffalo and studied in Pasadena, he’d become a messianic New Yorker whose office was located on the top floor of the iconic Flatiron Building. “I have found making recordings like environments gives me a certain communion with nature I have not had before,” he observed in a 1987 interview.[33]

Teibel went so far as to mourn humankind’s divorce from natural sound in an interview broadcast on an Austin TV station in the early 1980s. “The one thing I became aware of once I started doing this series,” he noted, “is that we don’t live the way people lived a hundred years ago.” Dressed in a grey, slightly ill-fitted suit and wearing a grey tie with yellow polka-dots, Teibel’s gold-rimmed glasses and Trotsky beard suggested he was a researcher, not a secondhand car salesperson. “Things have changed tremendously for us,” he continued.

“Now we’re so aware of heating and cooling, we isolate ourselves from nature. Even if you live in the country you don’t really hear nature sounds if you’ve sealed yourself off in this little box. You hear electronic sounds, you hear the telephone, you hear the radio, you hear the TV, but you don’t really hear much of what’s going on outside. I know for a fact that most people need those sounds, that living in a silent area is very difficult and it makes you very tense.”[34]

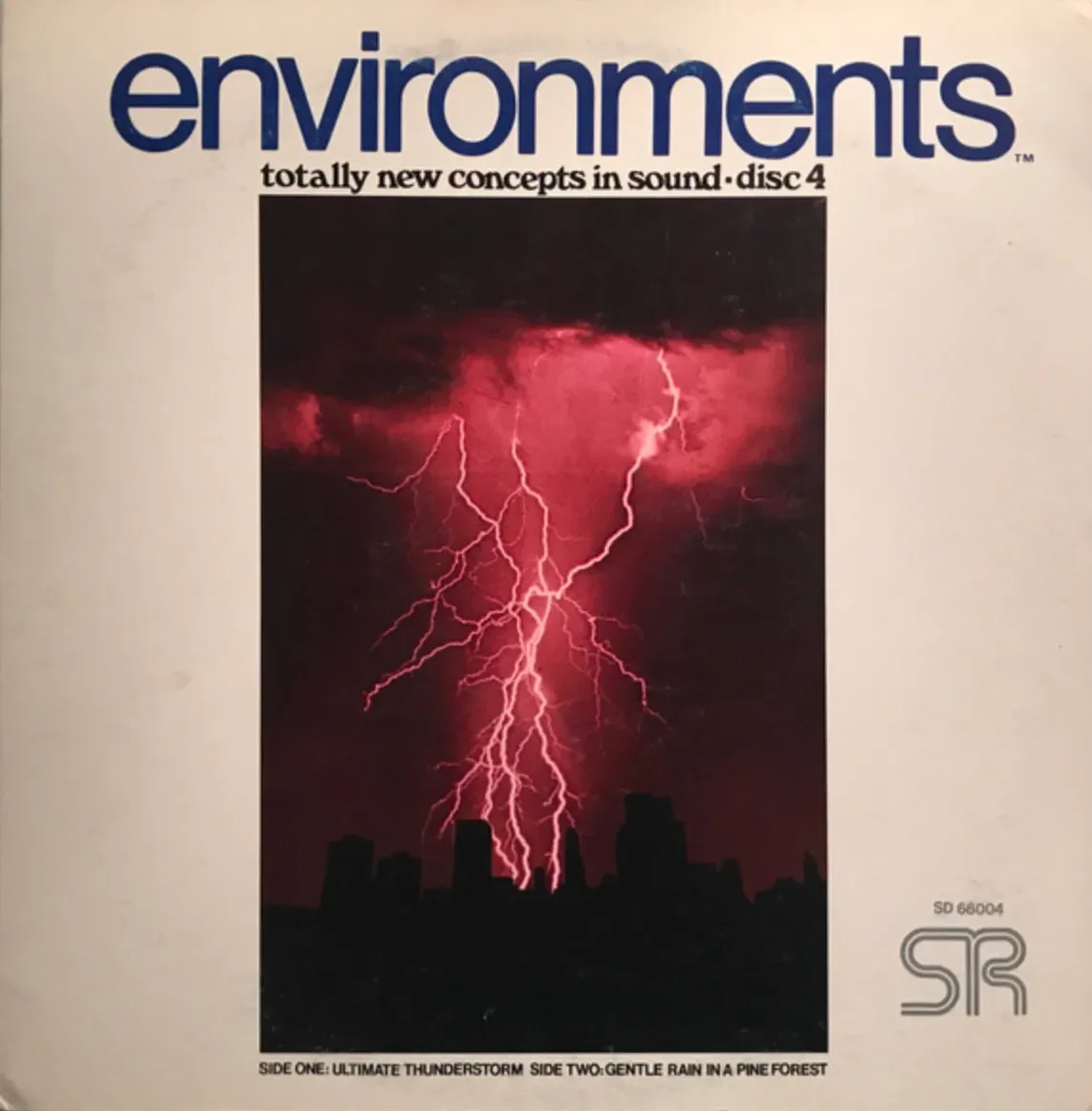

Admittedly Teibel ended up recording “Ultimate Thunderstorm” from the shower room in his New York apartment, window ajar, but this was only after he’d unsuccessfully attempted to record a thunderstorm while outside, getting soaked in the process. Even in the Okefenokee Swamp Teibel understood that the risk was partly of his own making. As he explained in 1975, he’d taught his dog to never bark while he was recording. Luckily just as the alligator crept towards the dog—probably not to add the crunching sound of nature to the recording—Teibel shone a torch on his frozen-with-fear, silent dog and stepped in.[35]

Environments Disc Four (Syntonic Research, 1974)

It’s no coincidence that Martin engages intensely with Teibel’s environments and not Payne’s Songs of the Humpback Whale. While Teibel conceptualises a natural environment that humankind has become divorced from, Payne captures one animal in order stop human endangering it. If Teibel’s broadranging conceptual analysis is correct—and Teibel was concerned with analysing the listener experience in a way that went well beyond Payne’s immediate field of interest—the environments recordings would bear repeated listening, potentially enabling the listener to enter the alpha state, whereas the distinctive linguistic patterns of Songs would soon be unconsciously memorised and would become less interesting, plus its composition would be less meditative. If Songs had a much greater impact on eco-consciousness, Teibel’s way in was more analytical, more engineered and more ambivalent. Its more developed aesthetic introduced a level of complexity that encourages repeated listenings. Teibel’s work also tapped into countercultural aesthetics in a significantly more open-ended way.

First defined by Theodore Roszak, the countercultural movement originally sought to “invent a cultural base for New Left politics.”[36] It challenged the inauthenticity, poverty and oppressiveness of an everyday life defined by hierarchical power, paternalism and authoritarianism by discovering “new types of community, new family patterns, new sexual mores, new kinds of livelihood, new aesthetic forms, new personal identities on the far side of power politics, the bourgeois home and the consumer society.”[37] Rooted in the thinking and practices of the anti-war, back-to-the-land, Black power, civil rights, ecological, feminist, gay liberation and psychedelic movements, as well as a “stormy Romantic sensibility, obsessed from first to last with paradox and madness, ecstasy and spiritual striving”, counterculture placed an emphasis on individual as well as societal change, yet the overall emphasis was on the latter.[38]

Yet as the era unfolded counterculturalists placed increasing emphasis on individual change for the purpose of straight-up individual change, whether that be rooted in matters of diet, exercise, spiritual practice, yoga, and so on. That’s not to say that these areas couldn’t cultivate an outward-looking perspective, merely that it became more and more common for them to operate according to self-centred ends—the maximisation of the self, not the many or the entirety. In a related development the countercultural movement also became a hotbed of source material for a spiralling range of commodity products and services while its participants formed a significant grouping within the developing consumer market. Yet even in these moments of commerce and accumulative capitalism, there is no final ending. As Martin might say, their paradoxical quality promised not merely an end point but also a new opening while their hauntological quality dictated that the history couldn’t be wiped out.

It would be easy to argue that the environments series nestles in the commodified self-help end of the countercultural era. So much of the discourse Teibel introduces on the theme of the listening experience revolves around individual optimisation plus he aimed to make money. As Mike Powell argues: “Teibel sold these albums in part with the promise that they would help us sleep better and focus more. The moral is a capitalist one at heart: Our best selves and our best working selves are the same thing. That we have to twist mother nature’s arm in order to stay on top is collateral damage.”[39] Teibel did pretty well out of the promise. By the end of 1974 he’d released seven albums with sales for his first release topping 300,000. “Disks 1, 2, and 3,” Teibel commented in 1975, “are selling as much this year as they did in 1970 and 1971.[40]

Irv Teibel reviewing papers with WEA/Atlantic Records executive. Sourced from the Irv Teibel Archive, https://www.irvteibel.com/galleries/syntonic-images/

Yet you don’t have to spend long reading Teibel’s interviews to understand that he was never going to turn Syntonic Research Inc. into a profit-reaping machine. In his mid-20s he wrote a letter to his parents saying that his ultimate objective was “to make a lot of money doing something I will be happy doing.”[41] In the end the “something” made him happy, inasmuch as environments became his purpose in life, and when we discover our purpose we can become happy, but wasn’t best-suited to making money. One loaded example: environments 1, his best-seller, didn’t sell anything like Songs of the Humpback Whale, which went multi-platinum. Teibel spent countless hours with recording and editing equipment across a period of ten years to produce a streamlined collection of musique concrète recordings, and additional countless hours consulting with consumers of his albums, in order to release 11 albums at a rate of 1.1/year. Sales just about supported the expense of maintaining the business. He couldn’t have sustained Syntonic Research, Inc. for 11 years if he’d paid himself an excessive salary.

In terms of morals, Teibel also opposed capitalism’s controlling intent. He turned down opportunities to design sound for public areas because, as he told Hans U. Werner of the German public-broadcasting outlet Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln, he opposed the idea of “subjecting people to something they have no control over.”[42] In particular he didn’t want to mirror the subliminal persuasion techniques deployed ubiquitously in elevators, large retail stores and other commercial outlets that forced people to listen—an experience that could even encourage them to begin to dislike a recording they thought they liked because now it was associated with regulation. “Muzak is not marketed to please people,” he added to Werner. “It is used to control people. Make them work fast, make them pay more attention, synchronise their efficiency. The fact that you cannot control it makes the difference.”[43]

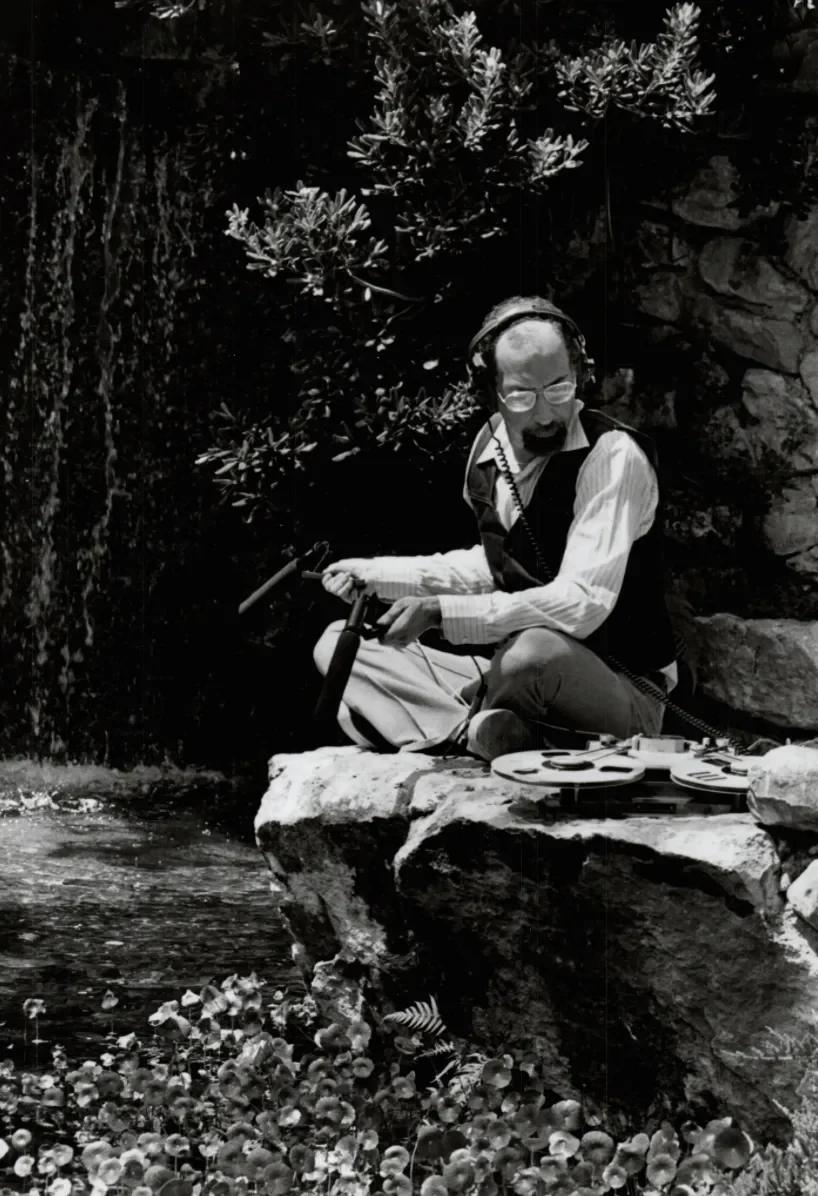

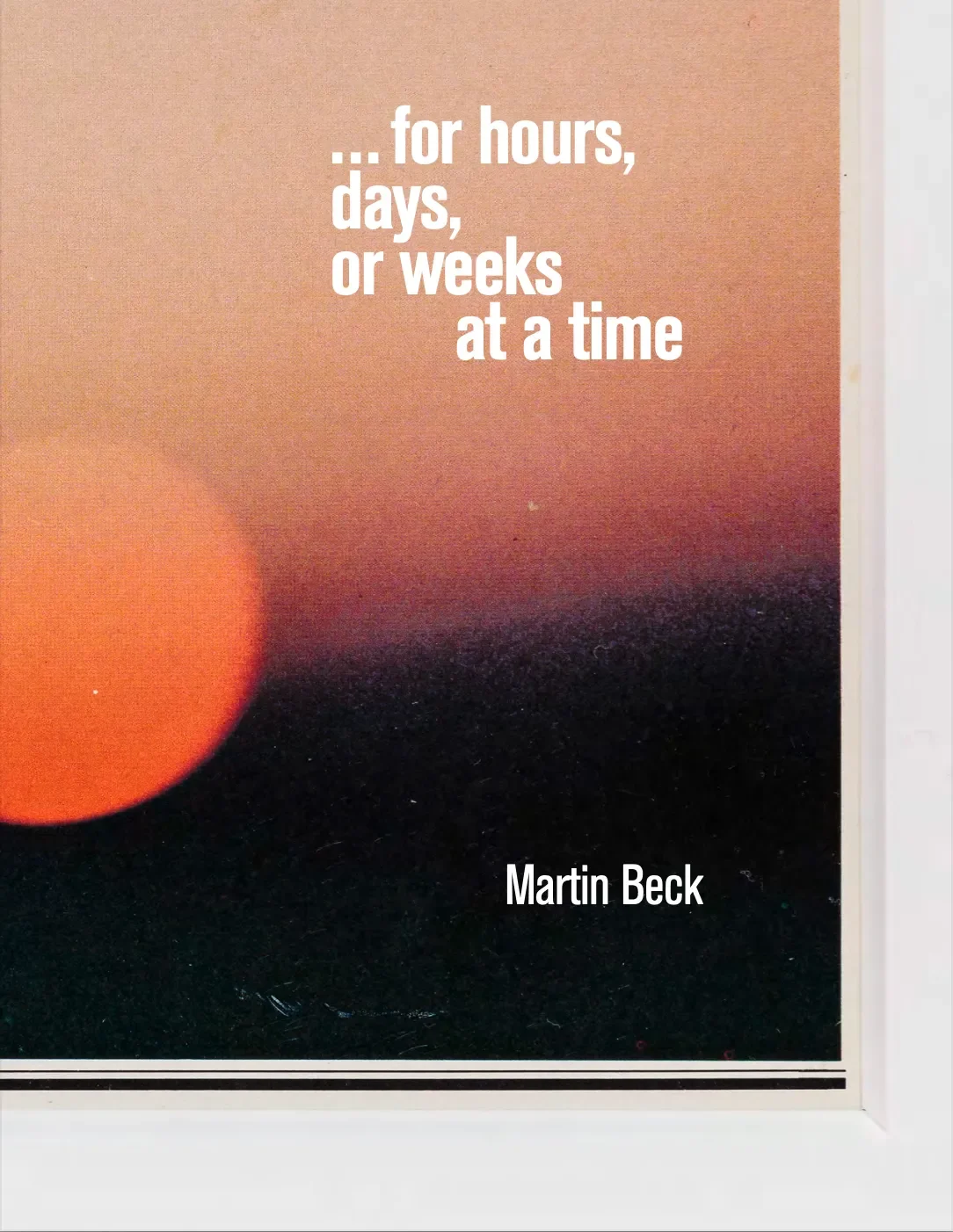

Hans U. Werner interview with Irv Teibel, Hans U. Werner interview with Irv Teibel, “The most important thing I do is listen”, W. Deutsche Rundfunk broadcast, 16 October 1987. Re-edited 17 May 1988. Further edited and abridged by Martin Beck, 2024. In Martin Beck, … for hours, days, or weeks at a time. Catalogue. Ridgefield, CT, and New York: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum and Gregory R. Miller & Co., 2025, 76-77.

Teibel’s belief that listeners should choose whatever they listened to might sound modest in terms of political ambition yet it’s expressive of one of the countercultural movement’s core beliefs: that we should strive to free ourselves from corporate-governmental-technocratic control. Demonstrating Teibel’s foresight, has this goal ever been more important than it is now?

Nor did Teibel’s audience ever straightforwardly resemble the avaricious, opportunistic, post-Fordist capitalist class that began to grow rapidly during the late 1960s and has yet to look back. However much the objective of self-maximisation might be connected with neoliberal capitalism and its more recent nationalistic variants, Teibel’s extensive dive into this realm didn’t obviously contribute to neoliberal subjectivity. We know this through the extensive feedback operation Teibel developed via a questionnaire he slipped into every record release, to which one in seven buyers replied. This helped Teibel understand the striking diversity of his listenership, which ranged from students to helicopter pilots, psychologists and psychiatrists to priests, and people who wanted to make love to grandmas who would enter their own alpha state while knitting. This public stands apart from the narcissistic, competitive individuals who wanted to tune their minds in order to be their best capitalist selves and who would become intertwined with the multinational corporate end of neoliberalism.

It’s possible to cite someone like Steve Jobs and argue that the countercultural movement and what became neoliberal capitalism were always connected. Jobs says he took LSD ten to fifteen times between 1972–74 before he ended up on an ashram where he hatched the idea that became Apple. The psychedelic revelations of interconnectivity and freedom became a platform for a company that would go on to epitomise the neoliberal economy and for a long period stand as the most valuable on the planet. Yet even if important aspects of the countercultural movement were vulnerable to cooption the movement preceded and always exceeded neoliberalism while taking relentless aim at the accumulative, individualistic ethos of a manic-corporate world. If corporations grabbed all manner of ideas from counterculture, from introducing flexible working models to promoting ideas of freedom to allowing employees to dress casually to rolling out wellness programmes, they did this to win consent and enhance profitability, not because they cared about societal betterment.

Steve Jobs in India. Sourced from “Steve Jobs: An Entrepreneurial Odyssey”, Oscension: A Spiritual Guide to Business Growth, no date, https://www.oscension.com/steve-jobs-an-entrepreneurial-odyssey/. The article notes: “In the mid-1980s, Steve Jobs faced one of the most tumultuous periods of his career: he was ousted from Apple, the very company he had co-founded. Much like a spiritual seeker is sometimes thrust into the ‘dark night of the soul’, Jobs entered a period of profound professional wilderness. This phase, however, was not the end but rather a transformative interlude that would ultimately deepen his entrepreneurial and spiritual journey.” In the United States capitalism and spirituality became one as the executive class coopted Eastern philosophy to give meaning to its acquisitive materialism, unparalleled contribution to widening inequality and plundering of the southern hemisphere’s natural resources.

There’s no meaningful way to compare a small business that focuses on its product, contribution to society/sense of purpose and commercial survival to a corporation that exists to maximise profitability, warding off (or buying out) competition and patenting everything in sight. Teibel might appear to be a recording engineer who merely caught what was already in the air yet in reality he was an attuned, highly selective artist who pioneered an entire oeuvre that relied heavily on editing. It just so happened he was also one of the few if only musicians who wanted to be heard rather than listened to. Unfortunately Teibel learned over the years that “people don’t use music for relaxation so much that they use it for excitation.” The commercial limitations of environments was built in from the start.

At least Teibel was happy to do what he did and stayed true to his vision as well as a gentle utopian premise that lay at its heart. “I never thought it would take off that fast nor that it could fulfil a need so universal,” he noted to Werner, choosing words that could have almost come out of the mouth of David Mancuso. “The more I work in this field, the more I realise I am dealing with universal sounds; sounds that transcend cultural tastes and national boundaries.”[44] In the end Teibel called it a day after the release of environments 11. “I felt that I had gone as far as I could go and, at that time, I wanted to turn my work over to other people to do something more with it,” he told Werner. “It didn’t happen.”[45]

Irv Teibel recording a stream in the mid-1970s. Sourced from the Irv Teibel Archive, https://www.irvteibel.com/galleries/in-the-field/.

Teibel, then, embodies a paradox. His work embraces aspects of individual and societal change yet nestles in a period when the corporate sector, corrupt and declining, began to appropriate countercultural ideas and practices to revitalise profitability. Since then the natural environment has become usable material for the corporate sector, from the landscapes that appear as ubiquitous screensavers to the booming wellness industry to any number of greenwashing initiatives. Sometimes the breadth of the corporate takeover can feel like its the end, but if we step back even for a moment we know that it’s not. The fact that Teibel does all of this and does conceptually makes environments a perfect subject for Martin.

I ended up buying a whole batch of environments releases in May 2023, mainly purchasing copies from sellers in the US as I was due to visit soon and the recordings were generally cheaper there. However, I made my first purchase, environments 3, in the UK. Side A was titled “Be-In (A Psychoacoustic Experience)” and amounted to an edit of a recording of the 1969 Easter Be-In in New York’s Central Park. “‘Be-In’ is the real experience of running barefoot in the grass on a beautiful spring day, surrounded by thousands of half-innocents exhibiting little, if any, trace of paranoia and guilt,” Teibel explained in his sleeve notes. “If you were ever at a massive, totally spontaneous gathering in 1969, we think you know the feeling we mean.’

Around the same time Martin first mentioned Teibel’s “Ultimate Thunderstorm” recording (or I finally took note of what he was saying). It dawned on me that this must have been the recording that David Mancuso played at the Loft back in the early 1970s, as recounted to me by the New York DJ Frankie Knuckles, an early regular at the party, during research for Love Saves the Day:

“David would get very atmospheric. He could have the most incredible energy going on in the room, and then all of a sudden he would create a tropical rainstorm. The room would be completely blacked out, and you would hear this crackling of thunder and rain, which became louder and louder. It was hot, and everybody would be standing there, some half-naked, whistling and screaming. Then you heard this wind blowing, and after a short while you would also start to feel it because he turned these fans on. It was as big as life, and if you were on acid it wasn’t your imagination—this shit was real.”[46]

I felt joyous that I’d finally put a finger on the source of that thunderstorm. I was also excited by the idea that inadvertently there appeared to be a direct connection between Last Night and Martin’s new work, or between the socially and sonically progressive intent of the Loft on the one hand and environmental records that could even add dimensionality to the experience of collective joy at a dance party on the other.

Then, just a couple of months ago, in February 2025, I was told that when David acolyte Larry Levan played thunderstorm effects at the Loft-inspired Paradise Garage, which he drew from Wendy Carlos’s “Spring”, the first track on Sonic Seasonings, and that David also played the Wendy Carlos recording. So maybe David didn’t played Irv Teibel’s thunderstorm.

One thing I am sure about is that years earlier David told me: “There was a series of records called environments that reproduced the sounds of streams, of the wind blowing, of the ocean.” At the time there were many other things I wanted to understand about David and the Loft so didn’t ask him more, now I wish I had. Even so, David can have only been referring to Teibel’s releases. The dots on the radar were converging on the same point.

3: The "… for hours, days, or weeks at a time" exhibition, Teibel’s materials, capturing and framing environments, and David Mancuso

I wasn’t able to attend the opening of … for hours, days, or weeks at a time so followed developments from afar and decided I’d write something, although at the start I wasn’t sure if this would be a short social media post or something more substantial. The latter seemed unlikely as at that particular moment I was juggling a book long in the writing plus a new book idea that I’d become obsessed with.

After I looked through Martin’s exhibition catalogue for the first time I decided to write a fuller piece.[47] That was when I got to better appreciate that … for hours... not only amounts to an epic follow-up to Last Night but also connects to that series of works in multiple ways. It draws attention on one person’s lasting yet under-appreciated contribution to new ways of being and perception, this time turning to the idiosyncratic, thoughtful and intense figure of Irv Teibel instead of the idiosyncratic, thoughtful and intense figure of David Mancuso. It delves into the social implications of the material in question in a way that’s compelling and entrancing. It also raises a series of related questions. What do fragments of counterculture suggest to us about the past and the present? What do their paradoxes close down and open up? What’s the relations between mediation and the thing itself?

Martin Beck, … for hours, days, or weeks at a time. Catalogue. Ridgefield, CT, and New York: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum and Gregory R. Miller & Co., 2025.

I took the only option available and decided to review a show about mediation through mediated source materials rather than experiencing the thing itself. Everything that follows is written from afar and is impressionistic. Martin did, however, kindly speak me through the organisation of the show.

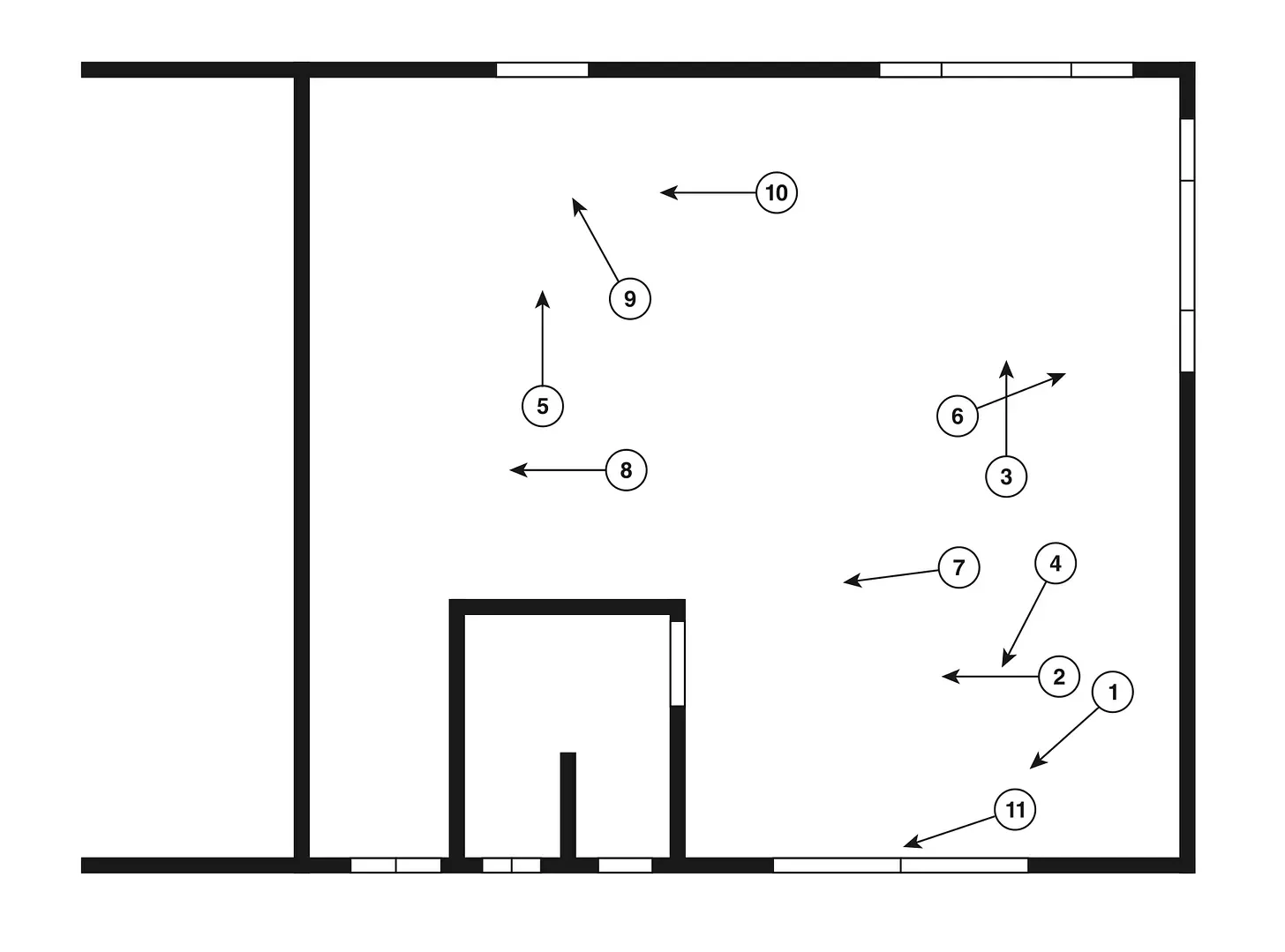

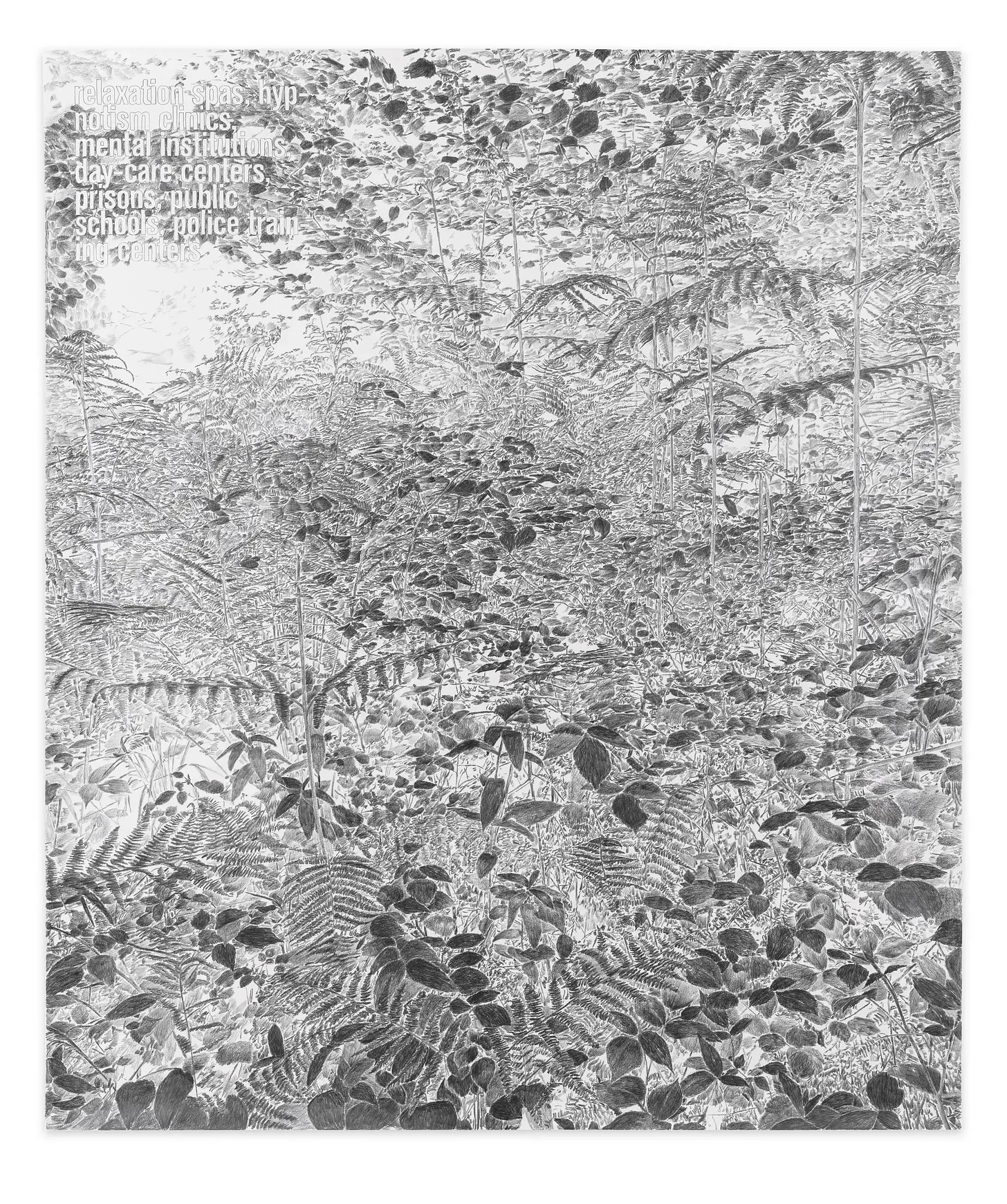

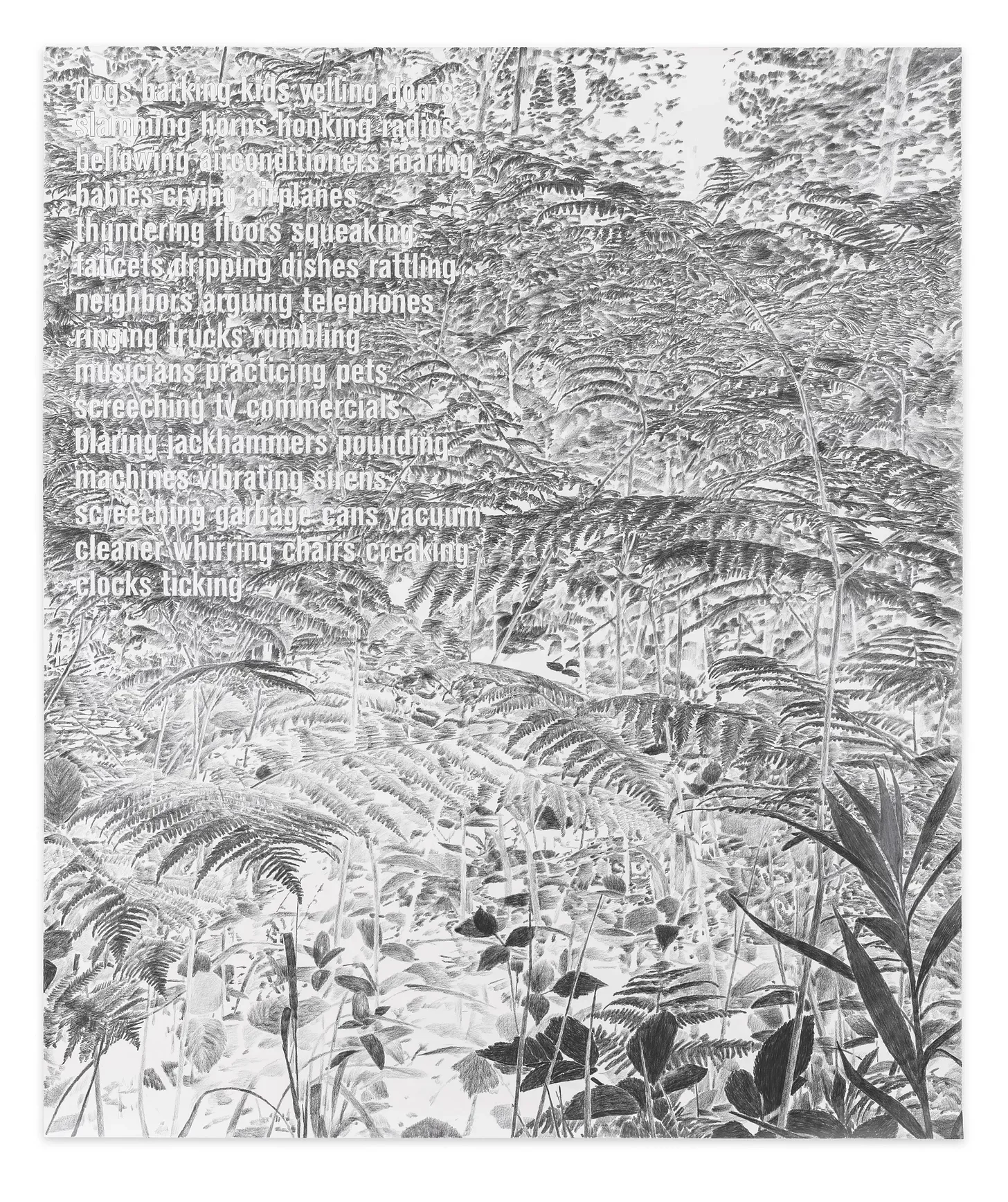

The museum entrance leads into the main lobby, the first exhibition room, which contains the introduction to the show, four large drawings of ferns and various other artworks, some of which draw directly on environments sleeve covers. The lobby connects to a video room as well as a corridor that features a display. The corridor also leads to a third room that presents further artworks and marks the conclusion of the exhibition.

If David Mancuso hovered as a submerged figure in Last Night, Teibel occupies a similarly liminal presence in … for hours… That seems fitting given that, like David, Teibel was devoted to the thing itself and showed little interest in self-publicity or self-aggrandisement, to the extent that he doesn’t include his name in any of the 11 environments releases, preferring to list Syntonic Research, Inc. as the producer. If the Loft doubled as a petri dish for social exploration the scientific-sounding Syntonic Research provides the setting for Teibel’s experiments.

Teibel enjoys a ubiquitous yet semi-ghostly role in the exhibition, largely appearing via a series of materials drawn from his archives, held in 13 containers at the New York Public Library, along with a series of original artworks that draw on his album sleeves.[48] Positioned in the corridor, the items include feedback cards, sleeve notes, sketches for advertising graphics, an advertising photo, marketing copy that resembles experimental poetry, slide sheets, miscellaneous handwritten and typed notes, logo designs and photographs.

Martin Beck display of Irv Tibel materials. Photo by Jeffrey Jenkins Project, courtesy Aldrich.

Almost entirely located in the first exhibition room, the artworks revolve around a series of interconnected pieces titled equilibrium from 2023, which reframe five Teibel album covers, as well as another series, Set/Setting from 2021, which juxtapose album information on the psychoacoustic experience and listening test responses through imaginative typography and use of colour.

equilibrium: Ultimate Thunderstorm, 2023

equilibrium: Intonation, 2023

equilibrium: Dusk at New Hope, Pennsylvania, 2023

Detail from equilibrium: Dawn/Dusk in the Okefenokee Swamp, 2023

equilibrium: Gentle Rain in a Pine Forest, 2023

Detail from equilibrium: Summer Cornfield, 2023

Martin’s introduction of two other pivotal elements—in place (environments) (2020), a 121-minute film with sound, and four very large drawings of ferns, or fernscapes—offsets Teibel further. The three parts coexist, balance and offset one another, opening up a non-binary conversation. Significantly, instead of presenting the environments recordings in a concentrated listening area furnished with sofas, cushions and maybe even blindfolds, or having them play through speakers positioned in every room, Martin arranges eleven extended extracts to be heard only via the soundtrack of in place (environments), so in the video room and secondarily in the corridor and lobby into which it bleeds. In this Martin observes Teibel’s recommendation that his recordings be heard rather than listen to.

The foregrounding of Teibel’s marketing materials above, say, an immersive music experience or detailed biographical information encourages us to consider how our relationship to the natural environment is heavily mediated. This is the recurring theme of the exhibition. If Teibel was renowned for developing the environments recordings “to enhance mental and physical states”, art historian Gabrielle Schaad notes in the exhibition book, Martin “introduces Teibel’s sounds and archival materials as a form of critical historiography, producing artistic framing to reorient perception.”[49] Martin must have spent hours, days, weeks, or months, very possibly years trawling through Teibel’s materials. “It is one thing to plunder ‘the archive’ for a certain period look,” he noted in 2003, “it is another to attempt an understanding of how contemporary visuality and processes of communication are constructed from the fragments or ruins of the past.”[50]

Irv Teibel marketing materials, top left clockwise: Irving Teibel, logo for environments, 1969 or early 1970s; Syntonic Research, Inc., advertising card listing sounds that can be masked by environments records, early 1970s; list with possible terms related to “The Psychologically Ultimate Seashore”; Syntonic Research, Inc., advertising photograph, 1970s; Syntonic Research, Inc. list with possible terms related to environments record series, 1969; Syntonic Research, Inc., feedback card, 1970s. Photographs Jeffrey Jenkins Projects, courtesy of Aldrich.

The “Set/Setting” title, which references the argument made by Timothy Leary et al in The Psychedelic Experience (1964) that any psychedelic trip is shaped by both the mindset of the participant as well as their physical and social environment, draws attention to the connection between Teibel’s psychology, psychedelics and the framing of environments. Martin’s deployment of the phrase suggests all sorts of things: an interconnection between Teibel and the psychedelic pioneers of the 1960s, a further connection between the way that psychedelics work and the way that environments work with regard to transcendental states, and the need to prepare the setting to maximise both experiences. Nor is the link Martin establishes between environments and the psychedelic experience random. High Times described the recordings as “highly addictive.”[51] If that indicates that some people might have listened to the environments series on psychedelics, how did that work?

Martin Beck "set/setting" series: "Set/Setting (SD66004, SD66005)”. Photographs Jeffrey Jenkins Projects, courtesy of Aldrich.

Martin Beck "set/setting" series: “Set/Setting (SD66006, SD66010), 2021”. Photographs Jeffrey Jenkins Projects, courtesy of Aldrich.

Martin Beck "set/setting" series: “Set/Setting (1/10XP, SD66002), 2021”. Photographs Jeffrey Jenkins Projects, courtesy of Aldrich.

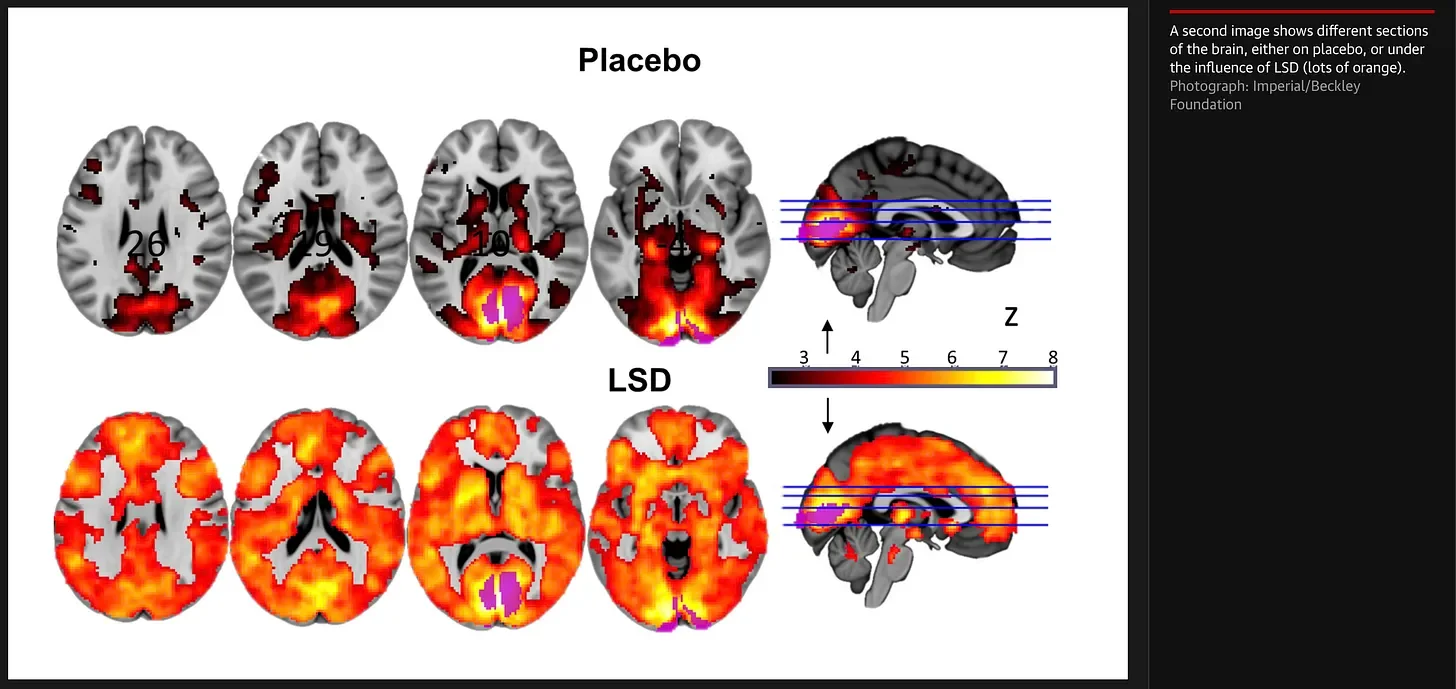

Generally the psychedelic experience enables a certain freeing of the mind and the body. MRI research conducted in 2016 by David Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and a former UK government drugs advisor, confirmed that the psychedelic experience is rooted in LSD’s principle if not sole effect, which is to increase the porosity of the walled-off sections of the brain.[52] Depending on the dosage, this triggers and heightens cross-wall neuron communication, which is often experienced as revelatory.

Image of the brain on LSD from Kate Wighton, “The brain on LSD revealed: first scans show how the drug affects the brain”, Imperial, 11 April 2016.

If we hear environments while conducting another activity, which is how Teibel suggested they be experienced, we’re likely to do so through our frontal lobes, which help control thinking. Unconsciously we would use our parietal lobes, which interpret sensory information. But if we listen on psychedelics we should really pay attention to, indeed, set and setting. If we find ourselves indoors for part or all of the trip, how might we maximise the experience in terms of making the room as comfortable as possible? An environments recording, if played, would become part of the environment and in this situation we would activate our temporal lobes, which process information related to sound, taste and smell, as well as our occipital lobes, which connect images to our memory, plus these two lobes would communicate with each other as well as the first two lobes. Connections would ensue that are specifically related to our experience and immediate environment yet would nevertheless feel revelatory, and we might say or feel, wow.

“Set/Setting” inevitably brings us back to David Mancuso, including a David episode that I describe in Love Saves the Day and that I know Martin finds fascinating.[53] It centres around David’s description of listening to the sound of a little whirlpool at the Blue Hole, a short ride away from his then upstate home, more of a shack, in the woods of Mount Tremper. David was tripping at the time and became enthralled by the experience, which was so sonically detailed he imagined he could almost hear “the history of life, not in words but in music.” David added: