I interviewed Daniele Baldelli twice in 2006, once in London in May and a second time in his Italian home in Cattolica, near Rimini, in July. The first interview followed a rare international appearance by Daniele at Plastic People, where his trippy-funky sound and mesmeric mixing combinations blew away a small but ecstatic gathering. The second came during an extended visit to Rimini and amounted to one in a series of interviews conducted with Italian DJs following a request by Maurizio Clemente, the Italian publisher of Love Saves the Day, that I write a history of Italian DJ/dance culture (Amore salva il giorno?). Although much of the interviewing was fascinating it soon became apparent that I wasn’t going to get around to writing that history . In large part it was because I had too many other books that felt more urgent, beginning with the Arthur Russell biography and continuing with the book that’s become Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-83. As soon as it became clear that the new book wasn’t going to get past 1983 I realised that the Italian book simply wasn’t going to happen, and although that came with all sorts of regrets, I recall also concluding that I didn’t feel that the recording side of Italian dance culture filled me with enough enthusiasm to want to pursue that project; indeed even the Italian DJs I interviewed seemed to have at best fleeting interest in Italian domestic music releases. Along with the challenge of conducting interviews/research in Italian, that seemed to foreclose the Italian history—a history that I hope someone else will write, because there are important stories to be told. But there’s no reason to let all of those interviews gather dust, so I thought that I’d try to publish some of them, beginning with the one I remember most clearly. Electronic Beats agreed to run with the idea and the full version of the interview is available here.

/

You first started to DJ in 1969 at Tana Club in Cattolica. How did that come about?

In Cattolica there was a little club called Tana club and I was there like a client, a dancer. I think it opened maybe at the beginning of ’69, not before. Tana was the first discotheque in Cattolica. Everyone used to say that the man who opened Tana club worked in Paris for many years and he saw the discotheques there. I was very young. One boy played records and after three months this boy went away and the owner of Tabu asked me if I wanted to play records. He noticed me because I was looking at the DJ all the time. So I started, but the owner of the club bought the records and he told me how to play. He stacked like a newspaper and said, “You start from this and you follow the line and when the line is finished you can choose another line. He made the programme. There were no headphones, no mixer, no monitor. You just put the record on at the beginning and when it was finished you started the next one. It wasn’t a problem if there was silence between the records and there was no issue around b.p.m. At the time the people were used to dancing to a song and then stopping and then dancing in a different way to the next song.

What music did you play?

Most of the music was rhythm and blues. Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Rufus Thomas, Ann Peebles, Arthur Comely. This is what we called black music but there was also white music, from UK more than the States, so I played the Stooges, Atomic Rooster, Pink Elephant “Gimme Gimme Good Lovin’”, Desmond Decker “Royal Lights”.

So what year were you born?

In 1952.

And you lived in Cattolica?

Yes.

Were there other clubs in Cattolica?

In 1969 there were dance halls featuring live groups that played music. But after Tana club a lot of little clubs opened. The Adriatic Coast was was full of little clubs in that period. You found one every kilometre. At the time everyone liked to go to clubs. They were something new. Either you went to the cinema or to the club. Because Cattolica was a tourist spot there’d be 15 clubs open in the summer and three in the winter.

From Tana you went to a club called Tabu—is that right?

Yes, maybe in November or December 1969. I went to this other club and the owner of the club never bought records. I said, “Listen, we need more records!” It’s always the same, so I told him, “Listen, you pay me more money and I buy the records.” So all the money I got I spent on records, because I was going to school, so it was a passion. I spent more on records than I made playing records. I didn’t like things that sounded very commercial, so if I bought a top ten record it was because I liked the B-side. Nobody told me what to do. This was my instinct. If I liked something I followed it. I played at Tabu from 1970 until 1976. The technology was also developing. During this period I started to use a mixer with two slides, which was a novelty. I don’t remember when I started using headphones. But I had two turntables. ELAC is the name—it’s a German turntable. It was automatic. You pushed a button and the arm went by itself. So we had to think how much time it needed to get to the record. Then came the Lenco turntable. It had a little lever for 33, 45, 78 and 16! After a short while I learnt that if I took the lever not exactly on 45 and a little bit nearer 78 it turned faster, so I tried to adjust the speeds, just to reduce the difference between the tempo, but without mixing.

Baldelli on the Tabù dance floor, 1972.

What was the dynamic of the night at Tabu?

At the beginning all the DJs played not only fast but also slow music for slow dancing. The method was to play five fast records followed by three slow records, all through the night. After one year, by maybe 1971, we played maybe ten fast and three slow, until we arrived at a part of the night where we would only play fast records, with one break in the middle of about ten or fifteen minutes where we played slow. Baia degli Angeli opened in 1975 and there they played fast music all night long. So we started to do the same around 1975 or 1976. We played like this because it was normal to do it like this.

What music were you playing at Tabu?

Black music and white music. I lived in Cattolica so I bought 7" singles in shop in Cattolica. I was working for 2,500 lira a night and at that time one 7” cost 600 lira, so if I worked one night I could buy three 7” singles. An album cost 3,300 lira, but it was very dangerous to buy them, because you couldn't listen to them, so we spent a lot of money hoping that there’d be a good song to play, sometimes buying an album because it had a nice cover and we thought that maybe there’d therefore be a good record inside. The shop in Cattolica wasn’t a specialised shop. It just sold the hit parade—I was bought records like Desmond Dekker “Israelites”. But at the same time, my crazy mind was looking for something different and so—I don't remember how—maybe the boss of Tabu, Renzi Lino, told me, “I know a shop, in Switzerland there is a shop, Radio Lugano, where they have import records.” He took me there in his Porsche. Maybe he was going there anyway to see some girl and thought it would be good if I bought records. I ended up going back maybe three of four times by train. The records I found in Radio Lugano were very different. In Cattolica 90% of the shop was Italian pop. But in Radio Lugano I found disco. Then in about 1975 a big shop opened in Rimini, the Dimar. It was a big shop and they stocked everything—a lot of classical music, pop, indie, polka, rock, disco, everything. But you couldn’t listen to the music. You just had to look at the covers and speak with the salesman. You’d say, “Hey, do you think this is good?” And he’d say, “Of course, this is very good!”

Can you remember some of the records you played during this period?

Some records from this period are important. For example, “In Zaire” is an African song from Johnny Wakelin. I played this in Tabu and then later in Cosmic and I still play it today. I also play today Johnny Taylor “Who’s Making Love”. I also play Rufus Thomas, Earth, Wind and Fire, the live album [Gratitude]. And of course there was James Brown. In Tabu I played a lot of James Brown. Tabu had close circuit TV and the first video recorder, a huge machine. It was the only place where they transmitted live concerts, so we recorded a live concert of James Brown and I played the concert on the TV and people danced. I played the audio and the video exactly as it was. You can dance to everything by James Brown.

Was this period important to the way you developed as DJ?

I was doing everything instinctively so I didn’t think a lot. But when Baia opened we saw for the first time these two DJs executing mixes. Of course at that time mixing meant mixing maybe three or four beats, and sometimes they just cut.

This is Baia degli Angeli, right? Can you tell me how you heard about it and what made it different?

I went to Baia some months after it opened because everybody was speaking about it. I heard about it first when a young barman at Tabu was contacted and asked to work there, so I knew something very big and very different was coming. We also started to see all over Cattolica and maybe also Rimini the logo of the club, the angel, without any writing. So we looked at this and thought, “What is this?” Then after a few months everybody started to say, “Now Baia degli Angeli is opening!” It was also a beautiful club. Everything was white, whereas in Tabu everything was dark. Because of that the spotlights were very effective; if there was a green light then the whole club turned green. Seeing the whole club change colour had a really big effect. And another thing that was different is it was the only club that stayed open until 6am, even 7am; all the others closed at 3am. Then the other big difference is they had these two American DJs, Bob Day and Tom Season. They came from New York and for at least the first six or eight months they had music that we’d never heard before because import/export hadn’t started. They had everything from TK Records, the Philadelphia Sound, a lot of 12” singles, a lot of free promotional records that nobody knew.

So Baia created a big impression.

The first time I went was the summer of 1975. Then in the summer of 1976 I went regularly. I worked until 3am and then at 3:30 I went to Baia and stayed for one or two hours. I looked at 2,000 people—beautiful people, beautiful girls—and I also became friends with the DJs. We thought Bob and Tom were crazy because they played with records that were warped. One afternoon they came to Tabu when I was playing. I was afraid and at the end of the afternoon Tom came to and said, “You are very good, but why don't you take away the rubber?” To mix with your hands you have a slip mat but when you buy the turntable there is rubber and the vinyl can’t slip, so you take away the rubber and replace it with a slip mat. But at the time you couldn’t buy slip mats, so they took away the rubber and put a 45 single instead. This was why their records were all wobbly.

How come they came to Baia?

Because Giancarlo Tirotti was rumoured to be lovers with Carmen D’Alessio [a New Yorker who worked in fashion and became Valentino’s PR chief in Rome]. He went to New York and met Tom, who was a friend of Carmen’s. At the time there were a lot of little underground clubs in New York and Tom and Bob had maybe played the first hour in some important club. Tom came to Baia because he was known by Carmen and Tirotti. Bob came two months later because he was a friend of Tom. They were both gay men and they mixed records, and it was the first time I heard this. Sometimes the mixes were good, sometimes not, but this was their style.

Did they have a mystique about them?

Yes, of course. In Italy everything that was not Italian is the best. The United States was the leader in disco and rhythm and blues and was very important. Italian music is rooted in Pavarotti and the waltz. We don’t have a tradition of blues music, rhythm and blues, and funk, so all the music we got we got from the States or the UK. Only after did us Italians become better, ha ha!

So was Baia the most important discotheque on the Adriatic coast?

I think this club really changed nightlife in Italy. It was the first club that created this kind of musical situation that nobody had heard before, it was open until 6am and it was also this fashionable place. Everybody came from all over Italy. After that big, beautiful clubs started to open all over, but Baia was the first.

Elevator DJ booth at Baia, 1978.

Where was it located?

Gabicce, which is a little hill near Cattolica. It's a little tourist town. There’s Cattolica, then Gabicce. It’s a very beautiful spot. You can see all the Adriatic coast. I cycled there! It was only two kilometres. Baia was opened as a high end restaurant and sporting club, then it became a disco. The disco came later when Tirotti concluded that the restaurant wasn’t busy enough. It was a restaurant with a small disco. There was a swimming pool inside as well as outside, and the inside swimming pool became a dance floor.

What happened to Bob and Tom?

I don't know exactly. Maybe Giancarlo was tired of what was happening. He thought of Baia as a club for people who loved music but it changed. It became too crowded and there were too many drugs, so he sold Baia. The club was finished and one of Tom and Bob had a boyfriend in New York and the boyfriend wanted him to return, or something like that, so they decided to go back to the States. When Tom and Bob were about to leave they came to me and said, “We have said to the new owner the you can go to work for him.” At the same time someone else spoke to Mozart [Claudio “Mozart” Rispoli], who had also started to DJ, so we found ourselves together. They asked me if I had a problem with Mozart. I said, “No, this is good,” because I was afraid to be the sole successor to Tom and Bob. Before Tom and Bob left I asked them to give me their copy of Loleatta Holloway’s “Hit and Run”. I said, “Give it to me, please, I can’t find it anywhere!” Everybody was looking for this record. They gave me their copy, autographed.

What drugs were going down?

Heroin. Before people went out they might smoke, maybe take a bit of cocaine, but when the club became famous all over Italy a lot of people came from Veneto and Lombardia. All of the drugs came from Holland—the north—Holland then Germany and then Brennero, Bolzano and Verona. Verona became one place where drugs came into Italy, so people from Vernoa started to experiment and they came to Baia and at Baia there was a heavy heroin and cocaine scene. This wasn't in the mentality of Giancarlo. He didn't want to create a drug hangout. He wanted la musica. Personally, I didn’t take the drugs. I smoked a joint and I was sick. I tried cocaine and I couldn’t have sex. I drank and I was sick. So I took nothing.

So you started DJing at Baia.

I started in October or November 1977 and I stopped in August 1978 when Baia closed for good. I was together with Mozart and then Mozart had to leave for military service in February 1978. He came back after three or four months, so I played alone during that period. After it closed it reopened in 1979. At that point it was just Mozart and it lasted only one summer.

How did it work with Mozart when you played together?

We usually worked one hour or 90 minutes and then changed. We played midnight to 6am so we place twice each. I played 1977 and 1978.

What were you playing?

I was playing different kinds of styles—disco music but I didn’t play records with a lot of vocals or melody. I played more instrumental records, more aggressive records. Also, I don’t know if all the songs I played were disco. For example, I was even playing a song by J.J. Cale, “She Don’t Like, She Don’t Like Cocaine”. He’s like a country and western singer. This song was very popular. I also played Timmy Thomas “Africano”. John Forde was also a hit, and so was “New York City” by Miroslav Vitous, “Ju-Ju- Man” by Passport, “Spaciula” by Dogs of War, “Gluttony” by Laurin Rinder and W. Michael Lewis, etc. etc.

Was your taste different to Mozart’s?

At that time Mozart was maybe more funkier than me. But I also played funky records. When I played all night by myself I played ”Bolero” from Ravel, the long version of Kebekelektrik, a group from Canada - they made Bolero of Ravel the whole side of an LP, 15 minutes, and when I played this song as the last song of the night I introduced a lot of effects from Pink Floyd, Jean Luc Pontoon, some African chanting. The sound was disco, funky disco, some Eurodisco, some electronics. One of the records I played was Bunny Sigler, “Baby It’s Time to Twist” [from the album Let Me Party with You]. Another was The Destruction of Mundohra by Final Offspring, which was a disco track that sounded like it was the soundtrack for a space film. I called this “space disco”.

So if this is 1977 was Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” a big record for you?

Yes, in the beginning, but if a record like that ended up being played on Italian radio then I would play it for a month or two before being attracted to something different, something more strange, something not so easy. I like everything—everything—but what attracts me is always something that’s different. When The Destruction of Mundohra came out it was really different to the other records I was playing and this appealed to me. “I Feel Love” was a good song but it wasn’t as emotional for me as “Love to Love You, Baby”. Also, we were used to playing songs that were three-and- a-half minutes long, so when “Love to Love You, Baby” came out on the whole side of an album it was like listening to a whole story.

When you were playing at Baia did you pre-programme what you were going to play for the whole night?

Yes, I prepared a lot of things but I also left space for improvisation. The first night I prepared a track list and maybe during the night I realised that the dance floor wasn’t really appreciating what I was trying at one particular moment, so I changed what I was playing, of course. In the end I developed a lot of track lists but changed from one track list to another, depending on the mood of the dancers. I don’t know why but I was crazy about mixing. I always wanted to make the perfect mix, but this was sometimes impossible, because the records were recorded live and tempo was always changing. It was a really big problem and meant that some records were terrible to mix together. So at home I would put one record on a turntable and on the other I would try a hundred records, looking for the perfect mix, not just in terms of the beat but also what was musical to the ear. I would make notes on the speeds and how records would mix together. When musicians play they write down the music. I mixed in this way.

Can you tell me more about the crowd that went to Baia?

For me the people in Baia were classy but also freaks. They had good clothes but they danced for me. They came for the music. Later, maybe when I started to play with Mozart, there were more working class, people were wearing more casual clothes and there were more young people. But the danced with the same energy—although not the ones who took heroin, of course.

And there must have been a seasonal rhythm…

That was the case with most of the clubs on the Adriatic cost during this period. In the winter they were only open on Saturday night, although some of the smaller clubs also opened Friday and Sunday. During the summer all the clubs were open every night during July and August. Only Monday nights would be quieter. During the winter people would come from Verona and Brescia and Bologna and Rome, even Germany and Holland.

Can you tell me more about Mozart’s style?

When we were working together maybe he was a little bit more funky than me. But he also played disco. Afterwards we both changed a lot. After one year I went to Cosmic—this was in April 1979—and then in 1980 I changed everything. During that time he was maybe more into electronic music and jazzy funk, like Don Cherry. But after Baia we lost touch with each other. I played at Cosmic for four years and he played all over.

How did you get on with Mozart while you were at Baia? I hear there was a rivalry.

We became friends at Baia because we were working together. We didn’t have a problem with each other. I remember I appreciate his style. He was more immediate. Whereas I was better prepared he just came and played. I think he had studied piano for five years, so maybe for him it was easier to mix. I didn’t have a musical education so I had to teach myself how to do it—writing, preparing, listening, trying the mixes. So I found my own way. As for the competition, that was created by the people.

How come Mozart played alongside you at Baia?

There were five owners of the second Baia. Bob and Tom introduced me to one of the new owners. At the same time another boss of the club heard about Mozart. I remember them asking me, “Daniele, do you have a problem if you also play with Mozart? I said, “No, no, OK, OK,” because I had seen him play at New Jimmy’s and he had come to Tabu.

So your last night in Baia was in August 1978. Was there a big last night party?

No, because nobody knew that Baia was going to close. The next morning we woke up and were told that we had to close. By this point there was a new owner—Diego Leoni. The people said, “The police have been up there and arrested Diego Leoni.” I was only thinking that now I’m without work. I had in fact a bad period, until January.

What did you do during this period?

I played a few gigs but really it was a bitch. I was playing what they wanted to hear just to get some money. So in December 1978 or January 1979 I was spoke with Lino Renzi, the boss of Tabu, and he said, “Why don’t we make a party here in my club with you?” “OK, OK, OK, yes, yes, yes.” So I made a few calls to friends from Bologna and Modena, and I said, “Hey, now I play in Tabu again, come on, come on.” For the first night 600 people came to Tabu club. For the second Saturday, 600 people come to Tabu and 600 waited outside because the club was full. The third Saturday, 1,200 people. The police went to Renzi Lino and said, “You close by yourself, or we make you close.” So the story finished again.

So how did Cosmic happen?

I was working in Tabu, in one of these parties, and a big man came in with his wife and some friends. They introduced themselves to me. They said, “We are from Lago di Garda, Verona. We are opening a new club. We listened to you during the summer in Baia and we like your style. We would like you to play in our club. We'll open in the spring.” This was December, I think. And I said, “OK.” At that point it was something strange, because at that time if a DJed worked in a club he was the resident for life. But I said, “OK, I’ll come. I want the money you’re offering and I want a house. Please, not an apartment, a house, because I have too many records.” And so they found a little house by Lake Garda. I made about 50 journeys in my Citroen to take everything over.

So you moved to Verona.

Yes, because I was thinking, “Listen, if I play for you, I want the same money for the winter and the summer. I don’t care how many nights you're open. I need this money because I buy the same number of records in the winter as the summer. Then, if you’re open every night, 365 days a year, I don't care. This was my approach. And I said, “I want to work for me and my girlfriend; - she was my girlfriend and she became the girl of the cassa, the cashier.

And you ended up marrying her?

Yes.

Did you meet at Baia or before?

In Tabu, in Tabu. We were very young—18, 16. She was the girl who danced all night long, you know? She was crazy about music.

What's her name?

Margherita.

And when did you get married? Or if you are married?

Yes we are married from ‘85. We wait a lot of time. We just married because we had a son. And you know the grandmother they have, uh, tradition [laughs]. We just do it in five minutes, with not big ceremony [laughs].

So who was the owner of Cosmic?

Enzo Longo, and his wife, Laura Bertozzo. Enzo Longo is the son of a well-off family. His father was a famous dentist. He is also dentist. At the time he was 33 years old and he worked with his father. Laura Bertozzo had two Fiorucci boutique shops, one in Verona and one on the Garda lake. They opened Cosmic because they went to Baia and they liked it. They found this place in Lazise, which is the name of the town on Garda sea. This club was called the Mini Piper. The story he told me is that he bought this club, he left it closed for one year because he wanted all the people forget what it was before, and then he started to build Cosmic. He was thinking about it being a dance club—he liked to say, palestra da ballo, a dancing gym. The club was maybe for 700 people, and the dance floor was for 600 people. There was no place to sit down; only the dance floor and the bar.

Was it unusual to have a club without a place to sit?

Yes, very. And another very unusual thing is that because he really wanted to make something clean, for the first year no alcohol was served. So there was no alcohol and no place to sit down. The sound system was made up of a Macintosh amplifier and GBL loudspeakers. The lighting equipment was also very good and the dance floor was like the one in Saturday Night Fever. The DJ booth was like the helmet of an astronaut. After two years he made a new book that looked like a starship.

So Cosmic opened in April 1979. What can you tell me about the opening? What were your impressions? How was it different from Baia?

The music was similar to what I was playing at Baia, so funky disco. The only memorable thing is that the opening was scheduled for a Thursday. So many people came that there were maybe 1,000 people inside and 1,000 standing outside, so they gave the people who couldn’t get in a ticket and said, “With this you can come to the opening night we’ll hold for you on Friday.” On Friday so many people came again they organised another opening for Saturday. Then they did one on Sunday as well.

Cosmic DJ booth, 1979.

How did the atmosphere compare to Baia?

I was nervous, but I'm always nervous when I work. The booth was low, so I could only see the 10 people standing in front of me because the DJ booth was on the same level as the floor. The second booth was a little bit higher.

So you were the only DJ at the beginning?

Yes. Then at the start of 1980 I had to leave for military service, so the boss of Cosmic asked me if I knew someone who would work with me and substitute? I knew this guy, Claudio, Tosi Brandi Claudio, who called himself TBC. He was from Riccione. I asked him to come and they gave him the same treatment—a house, a job for his girlfriend. He also had all my records at his disposal! After two years we fought with each other and so for six to eight months another guy called Marco Maldi worked with me and TBC went away. This was in 1982. Then after six, eight or nine months Marco Maldo stopped DJing and then TBG came back. We worked together until the end of 1984, when the club closed.

How long were you in military service for?

It was supposed to be 24 months because I was in the navy, but I was 28 years old when they called me and I told them, “Please let me work.” I did a lot of illegal things to not to be a soldier. It was all fake. I stayed in the hospital pretending to be ill, pretending to be a drug addict, because the last thing they wanted in the army was a drug addict. I said I was toxic dependent. They said, “How?” So I made holes with an empty needle to make my arms violet and said, “Look!” I also took a drug that put me to sleep during the day and another one to keep me away at night. In hospital I would run out and go to work. You could make a soap opera about my military service. After 6 months I was discharged but for five I was always finding a way to go back to play. When I was away for that month I know that they made a party for one night for Mozart, Rubens and Ebreo—just one night.

So were you aware that there was this backlash against disco in 1979?

I didn’t understand what had happened. I was working every Saturday night and during the week I stayed at home on this nice hill with a beautiful panorama—all of Lago di Garda—listening to records. So how I went from disco, funk and the Philadelphia Sound to Depeche Mode, Gary Numan or Klaus Schulze, I don't know. I didn’t care what was happening outside. I was living on my hill, listening to music.

So the backlash against disco passed you by…

Yes, but what I think is that the music of disco in fact is really different. Until 1978 disco was a good sound. But then they started to mass produce records and it became different. It wasn’t as beautiful as before. But I think Gary Numan, Depeche Mode, Klaus Schulze, Brian Briggs, Jean Michel Jarre, Phil Collins, Mike Oldfield, or Sky Records—they didn’t make music for the dance floor. They made music just to make music. So this is how music came to me and once I had it I played it in the club.

Can you tell me more about how your music selections changed in 1980?

I would select “Bolero” by Ravel and on top of this I would play an African song by Africa Djolé, or maybe an electronic tune by Steve Reich, and I would mix this with a Malinke chant from New Guinea. Or, I would mix T-Connection with a song by Moebius and Rodelius, adding the hypnotic-tribal; album of Cat Stevens, and then Lee Ritenour, but also Depeche Mode at 33 instead of 45, or a reggae voice by Yellowman at 45 instead of 33. I would play a Brazilian battucada record and mix it with a song by Kraftwerk. I would also use synthesizer effects on the voices of Miriam Makeba, Jorge Ben, or Fela Kuti, or I would play the Oriental melodies of Ofra Haza or Sheila Chandra with the electronic sounds of the German label Sky. I was continually listening to the records at Disco Più in Rimini. Maybe I saw the new record by James Brown. I would say, “OK, James Brown, I know him, I’ll listen to this record,” and I would think, “It’s quite good.” But then I’d listen to a record by Gary Numan and I would ask, “Who is this? Ah, this is nice. It sounds strange and beautiful. I like it. It’s got a very nice break. I’ll buy it.” I bought a lot of records in this way. Also, I started to buy records for little parts that I could loop and re-edit using a Revox—a reel-to- reel tape machine. So I started to make tracks by cutting together 15 seconds of a record.

Did you buy the Revox in 1980?

Yes, I started this in Cosmic.

Did you buy the Revox specifically to do this?

I bought it specifically to make edits. I had been to studios and seen the way they were doing this and I thought I could do something similar. From the album Perfect Love Affair by the Constellation Orchestra on Prelude Records there’s a record called “Cosmic Melody”—it’s a disco record. It had the line, “Cosmic-cosmic- cosmic-cosmic, me-lo- dy, me-lo- dy.” I thought, “I need this sentence for Cosmic, you know?” But it was also too much fast—maybe it ran at 130 bpm. So I recorded it with the turntable at minus-10 and then I looped it together many times, so it lasted for three minutes. I also made these tapes and on every tape I included “Cosmic, cosmic, cosmic…”

Did you start to use any other electronic gadgetry at Cosmic?

In 1982 or 1983 I also bought a drum machine and because the brother of my wife is a musician I said, “Please set up the bass of Richard Wahnfried’s ‘Time Actor”, so he programmed this line for me. Then I asked a friend who was a drummer to create a specific pattern for me. I would play the drum track and mix in maybe 30 records—Antenna, RAH Band, others—so the drum machine and the record were playing at the same time. I never left the drum machine to run alone. When I took away a record I was immediately ready to put on another one. It became like a little show that I did for maybe three years, but only for ten minutes. If I did it for an hour people would say, “Go back home!” So it was like a little show during the DJ set. I’d also bring in some keyboard effects; I was making keyboards. Then when the first sample keyboards came out in 1983 or 1984 that opened a grande apertura, a big door. When I went to the shop where they sold musical instruments the boy said, “This is a sample keyboard?” “What’s that?” “You can record your voice and then you play your voice with the note.” So I said, “You mean that if I make, ‘One, two, three, four, James Brown,’ then I can play, ‘One, two, three, four, James Brown?’” “Yes, you can do it.” “OK!” So when I was playing 1984, 1985, 1986, I took my own turntable, my own mixer, my own monitor, three keyboards, two drum machines and two sample keyboards. I was really a DJ band! It’s for this reason that I always had a big car…”

What drum machine were you using?

The Roland TR-808 and also the TR-909, which I bought in 1982 or 1983. At first I used the Korg, which was like a typewriter. This drum machine only had preset loops and you could only manipulate the speed control. So you could choose “rock” and it played a rock pattern or “cha cha cha” and it would play a cha cha cha pattern. But you could speed it up or slow it down. I used to play a pattern from the drum machine, just to introduce something strange, something different.

And you also bought a keyboard in 1980?

Yes, a Yamaha CS-10, and because TBC was a little bit more musical than me—he could play the guitar—I said, “Hey, if I buy a keyboard maybe you can do something?” But I also wanted to be able to play and so I went to the brother of my wife and like a child learnt how to play, learning some parts to play in songs that I liked. I would say, “Teach me this melody!”

Did you introduce any other technical innovations?

I started to play with four turntables but I needed a partner to do this so I did it with TBC. I played the first turntable, mixed the second record with the second turntable and then had TBC put on a third record. When the three were playing together I would prepare a fourth record and then take away the first, so there were always two or three records playing at the same time.

And what music were you playing at this point?

Music was changing. I don’t know if there was a genre like folk or punk but I took from everything. I was playing all the electronic music from Germany and from England. The best label was Richard Wahnfrieds Innovative Communication and also Sky. There were artists like Klaus Schulze, Jean Michel Jarre, and there were lots that were less famous such as Clara Mondshine. Then there were these strange groups like Tri Atma—this was a group of German musicians with all the innovative keyboards or synthesisers, but they introduced also percussion and flute from India, so they mixed their own electronic music with ethnic music which was perfect for me. I also played a song by Paul McCartney, “Secretary”, and I’d maybe mix this with Olatunji, “Jingo” or Cat Stevens Izitso. I also played Brand X, who made a type of electronic jazz. I also played African music like Touré Kunda, Pierre Akendengue, Fela Kuti, Manu Dibango. Then there were elements of Brazilian music—Gilberto Gill, Jorge Ben, Tania Maria. All of this was the style that people started to call the Cosmic Sound in 1980.

I can see why you’d play Gary Numan in 1980 because Gary Numan was new, but how come you started to mix in Olatunji, which was from 1959, or Manu Dibango from 1973?

I did this without thinking, but now I think that music is timeless. It’s not necessary to only play records you bought the day before. I was being these records from Dimar, the famous shop in Rimini, which stocked all kinds of music. And if I maybe discovered a Jorge Ben song that would give me the impetus to look for others and so I had explored all the artists from Brazil—Gilberto Gil and so on. And then maybe I would also buy a record with only shit on it!

So you were still buying music in Dimar?

No, not only. When I was playing at Cosmic in Verona sometimes I would come back to Rimini, to Cattolica, and I would go to Dimar. Sometimes Disco Più would send me packages of records. Then I found a shop in Brescia and then LeDisque, a record store in Verona. Also, I knew this guy, this music lover, would go around the shop, like a collector, and he would come to me and say, “Daniele, I have found this record in the shop, do you want to buy it?” “Let me listen… Oh, this is nice!” When he saw what I liked he started to come to me with a lot of records. He didn’t work in the shop. He was just a collector—like a pusher.

Can you remember other records you were playing at Cosmic?

A lot of Cosmic music came from Japan, such as the Yellow Magic Orchestra—Ryūichi Sakamoto is the keyboard player—and also Logic System. I played OMD “Promise” and “VCL XI”, I played Liasons Dangereuses “Los Ninos” and “Avant Aprex Mars”, I played Tony Banks Charm. In the winter I played darker music and in the summer I played sunnier music—more reggae. I also played Roxy Music “Angel Eyes” slow at 33.

Do you know if other Italian DJs were conducting similar experiments?

I don’t know. At the time everybody was saying that Cosmic was more electronic, Mozart was more funk, Ebreo was more Brazilian. Maybe I was the one who mixed more types of music together. I made this big crossover. The exploration of the past to go into the future chimes with the work of many Modernists. Picasso drew on traditional African art… But a lot of artists have done this. The Rolling Stones recorded an album in Morocco. Try Atma are electronic musicians and they play with musicians India. David Byrne made an album with African musicians. So yes, we want to go into the future, but with the roots of the past—Lamont Dozier, “Going Back to My Roots”.

So how central was African or Latin music to the Cosmic sound? Or was it occasional?

Every year at Cosmic had its own character. In 1980 the music was electronic and dark. By 1983 it was maybe more Brazilian. In 1984 there was more funk, electro and fusion.

Italo music was starting to come through more strongly at this point. Did you play much of that?

I played Gino Soccio “Dancer”. It’s strange but most of the records I bought had an Italian in the line-up somewhere. There’s always an Italian in the middle. But in terms of music made in Italy, I played Klein & MBO a lot when it came out—the instrumental; I played Koto “Tokyo Revenge”—maybe I played the B-side instrumental and played it at 33 instead of 45; I played Easy Going “Baby I Love You”; I played Gaz Nevada “Japanese Girls”, which wasn’t a big track but ran at 103 bpm and was strange enough for Cosmic; and Koto “Chinese Revenge”, which came out in 1983, although this is really an electronic song that happened to come out in Italy. Otherwise I played the Cosmic Sound. I didn’t know what italo disco was. When Italians tried to record disco music it was considered commercial. Of a hundred productions maybe I’d play two. I never played Alexander Robotnick’s “Problèmes D’Amour” because it wasn’t the Cosmic Sound, but I played “Love Supreme” by Giovanotti Mondani Meccanici with Alexander Robotnik. I think people from America and the UK listen to a shit sound from Italy and it sounds new. I know this sounds a bit nasty. But us Italians look abroad and are very influenced this music, so maybe we are too critical. Maybe we didn’t realise that we were also doing something good. I’m also a victim of this. But when I listen to records in a shop the first thing I do is listen to the sound. I wouldn’t say no to something just because it’s recorded in Italy. Generally I thought italo was too commercial.

So how did the dance floor response to what you were doing?

One of the big things about Cosmic is people came to listen what I was doing. I think people came with the idea of, “What will Danielle Baldelli make us listen to tonight?” Before I would start to play people would talk and drink. Then I would start with my signal, some electronic effects that I put together—the sound track of Flash Gordon, a violin solo by Jean Luc Ponty, some effects—and they would start to listen and dance. It seems as though you also slowed down the tempo when you went to Cosmic. I did this a little bit at Baia and also in Cosmic. For the first half an hour of the evening I would play slow. It was the same in Baia, because there were some nice disco records that ran at 105 or 108 beats per minute. It was normal to start the evening with slow music and then to go faster. But in 1980, 1981 and maybe also 1982 Cosmic was only slow, by which I mean it never got to 120 beats per minute. At the most it would get to 115. At the start it would be 95, 98, then maybe 100 or 105 for two hours. Maybe it was because era bella, it was nice in this way, and maybe also because of the kind of drugs people were taking. They smoked a lot so they couldn’t jump like little goats. Now, looking back, I think that we played slow because it seemed natural to play slow. It wasn’t that people were smoking. It seemed that after uptempo disco playing slow was new, a novelty. Then there was also a matter of making mistakes, say putting on a record at the wrong speed and realising that it sounds nice. After that I tried this with all the records I bought.

Were you responding to the crowd, or was this where you wanted to go musically? Because a lot of heroin was being consumed, wasn’t it?

No, in that period we played slow because it seemed natural to play slow.

Did TBC play at a higher tempo?

Of course, because I would play for the first hour and leave him at 110 bpm and then he would play a higher tempo. Cosmic closed at 1am so I played 10-11, he played 11-12 and then we played half an hour each for the last hour.

Can you tell me more about the club setting and the crowd?

In 1979 there was no alcohol, nowhere to sit and the people who came to Cosmic were kids of upper-class parents who were mostly well-dressed. The owner of Cosmic said that people from Veneto drank too much and he didn’t want to have fights. During 1979 we didn’t have any problems with alcohol or drugs. Then in 1980, because the club became very famous, everybody came to look from different parts of the north—Bologna, Brescia, Venezia—and during the summer, the holiday season, they’d also come from the south because Garda lake is a holiday resort. People would also come from Austria. After one year the club started to sell beer and because of the music that was coming out at the time, changes in drug culture and changes in the crowd, the club became druggier. But the drug problem didn’t happen inside. It happened outside, because maybe there were 1,000 people inside, but outside there would be 2,000 people in the parking area with tents, loud speakers and so on. It became a place to meet and they would play tapes of my DJ sets.

Can you tell me more about the tapes?

It was a good business. I started doing this in Baia but the real business of selling tapes started in Cosmic. From 1980 onwards it was really a boom. Every week there’d be a new tape and I’d sell a thousand copies. One boy would come from Torino. He never came inside Cosmic to dance. Instead he arrived in the afternoon and said can I meet Baldelli and he came back every couple of months to buy all the tapes. He came back once with a Citroën Pallas and he told me, “This is what I’ve bought from selling your tapes in Torino.” At one point the authorities found someone who had bought the tapes and they made me go to a judge. My lawyer said, “OK, we have to do something but what has Baldelli done? We have to know the quantities involved. To work that out they had to listen to the tapes, find out the titles, ask the labels for information and then make a charge. After four years there was an amnesty.”

What happened to you working with TBC and then Marco Maldi? And how did Cosmic close?

TBC and I fought for the first time in 1982. One evening in the DJ booth he got upset and left without finishing his DJ set. This kind of prima donna behaviour made me cross. And I was even more upset because I let his personality overwhelmed me. Probably there was a kind of jealousy between us because people said that I was “the brain” and he was the showman. So the competition was about this. But the boss didn’t like Marco Maldi so much and eventually he said, “Come on, you and TBC were the perfect combination, so we started again until Cosmic closed. Police had already closed the club once and they shut it down again in 1984.

Baldelli Discography

Alan Parsons Project "Stereodomy"

Tony Banks "Charm"

Bazaar "Oriental Wind"

Birth Control "Hoodoo Man"

Carte De Sejour "Ramsa"

Fuhrs & Frohlilng "Strings"

Gandalf "Journey To An Imaginary Land"

Grauzone "Eisbaer"

Manfred Mann's Earth Band "Chance"

Neuronium "Invisible Views"

Ambrose Reynolds "Greatest Hits"

Irmin Schmidt "Film musik Nr. 2"

Conrad Schnitzler "Con 3"

Robert Schroeder "Mozaique"

Klaus Schulze "Macksy"

Shadowfax "The Dreams Of Children"

Tribute "New Views"

Vangelis "The Dragon"

Za Za "Za Za”

Selected Mixes

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C01 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c01-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C02 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c02-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C03 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c03-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C04 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c04-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C05 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-005-1979-daniele-baldelli/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C06 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-c06-daniele-baldelli-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C08 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c08-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C10 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c01-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C11 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c01-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C12 - 1979

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c12-1979/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C01 - 1980

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c01-1980/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C 02 - 1980

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c-02-1980/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C03 - 1980

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c03-1980/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C24, 1981

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c24-1981/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C25, 1981

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c-95-1984/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C33, 1981

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c33-1981/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C57, 1982

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c57-1982/

Cosmic - Baldelli & Marco Maldi C79, 1983

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-marco-maldi-1983/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C 95, 1984

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c-95-1984/

Cosmic - Baldelli & TBC C 110, 1984

https://www.mixcloud.com/Italian_AfroFunk/cosmic-baldelli-tbc-c01-1979/

Daniele Baldelli - 11th December 2015 By NTS Radio

https://www.mixcloud.com/NTSRadio/daniele-baldelli-11th-december-2015/

Daniele Baldelli * 3 Hour Boiler Room Mix

https://www.mixcloud.com/Tourist/daniele-baldelli-3-hour-boiler-room-mix/

If anyone knows how to party, it's author and promoter Tim Lawrence. The British born party boy, turned academic, has not only hosted parties with the late DJ legend David Mancuso but also written three books on the dance floor experience; Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music, looking into disco, decadence and beyond; Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, and Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor; a detailed history of 80s NY, and how the dance floor not only brought different worlds together but laid the foundations for Hip Hop, House and Techno. Featuring interviews with over one hundred DJs, party hosts, producers, musicians, artists, performance artists, dancers and more - including Keith Haring, Jean Michel Basquiat and Fab 5 Freddy - it's a must read for anyone with a passion for understanding how music subcultures are directly shaped by social and political events of the time.

Fast forward to the here and now, and Tim works at the University of East London, where he teaches music and is the Professor of Cultural Studies. He is also the co-founder of Lucky Cloud Sound System, who have been hosting legendary Loft-style parties in London since 2003; some of the best of which saw night turn into day at Shoreditch's notorious now sadly defunct Light Bar. We caught up with Tim, on the re-release of Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, to find out the parties that have inspired him the most… From Hot Wednesdays at the Hacienda, to Feel Real at The Gardening Club, Body & Soul in New York and beyond, these are the clubs that changed his life...

Hot, Wednesdays at the Hacienda, Manchester, summer of 1988

"One summer, while studying Politics and Modern History at Manchester University, I stayed in the city to work at a camp for kids. Some non-uni friends had heard that the Haçienda was supposed to be good on Wednesdays so we went to take a look. That night I heard house music on a sound system for the first time and was immediately captivated. It must have taken me all of ten seconds to get from the entrance to the nearest podium and hurl myself into the tribal dance. I later learned that we had walked into Hot, one of the formative nights of the Summer of Love."

The Gardening Club London

Feel Real at the Gardening Club, London, c. 1992

"This was the first place where I felt as though I'd found a party home. A collective of four DJs led by the Rhythm Doctor, Feel Real held down Friday nights in this intimate basement spot in Covent Garden. It was the first time I was exposed consistently to New York house and I soon started to give the Rhythm Doctor a lump of money to buy me whatever he was buying, i.e. I was hooked. When "Little" Louie Vega showed up to play a guest spot I more or less decided I was going to move to NYC."

Rhythm Doctor and Little Louie Vega, The Gardening Club

Sound Factory Bar, NYC, 1994

"I moved to NYC in the autumn of 1994 to study on the doctoral programme at Columbia University (I'd grown a little weary of my day job) and dance to Louie Vega's selections at the Sound Factory Bar every Wednesday night. At the time every Louie mix was essential and the SFB was the place where he played them first. It was my first experience of the multicultural NYC dance floor. The live shows were also something else—India, Barbara Tucker, Tito Puente… I felt like I was at the epicentre of the dance music universe."

Body & Soul, NYC, 1996

"I'd heard Joe Claussell play in Dance Tracks, where I bought records every Friday night, and I'd danced to François Kevorkian's selections in the basement of the Sound Factory Bar, where he supported Louie Vega and mainly stuck to disco classics. But something took over when Joe and François teamed up with Danny Krivit to launch Body & Soul in Club Vinyl. It was fun to see three DJs share the decks and each introduced their own flavour to create what seemed like the perfect blend. The dancing was intense!"

The NYC Loft, 1997

"I interviewed David Mancuso for the first time in the spring of 1997 and soon after went to my first Loft party. Initially I didn't know what to make of the experience. The party took place in a private apartment, the sound system sounded positively quiet and at the peak of the party there might have been six people in the room. But there was something compelling about the open atmosphere, the clarity of the sound, the range of the music and the absence of DJ trickery, and by the time Mancuso held his 28th anniversary party the following February the floor was ready to explode with community happiness."

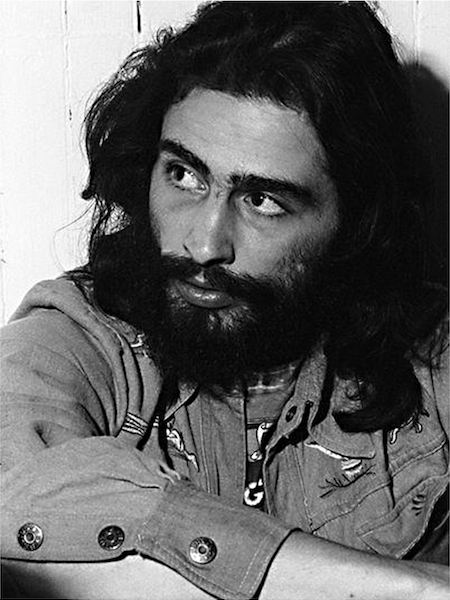

David Mancuso

The Loft, London, 2003

"As Love Saves the Day was going through production, David Mancuso approached me and Colleen "Cosmo" Murphy to propose that we start to host Loft-style parties in London. Joined by Jeremy Gilbert, we held our first party at the Light in Shoreditch in June 2003. David stayed in London for five days to shape the party in the image of the NYC Loft, from checking the size of balloons to visiting sound system companies to working out where to position the equipment to thinking through the lighting. Attended by friends and friends of friends, the party was one of the most joyous I've attended. Thanks to the foundations laid by David over a period of years the parties are still running today."

David Mancuso presents The Loft, 1999

The NYC Loft, 2016

"I travelled to New York in October 2016 to launch a new book, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-83, and timed the trip to coincide with a Loft party. David was kind enough to offer for the book to be sold at the party but didn't attend, having pulled back from attending his own party incrementally, in part because, radically anti-ego in outlook, he wanted to get to a situation where the parties would run successfully without him. The community vibe, beautiful sound and shimmering atmosphere of the October party confirmed that his dream had been realised. He passed away a month later."

This article was originally published on i-D, you can access it here (pdf).

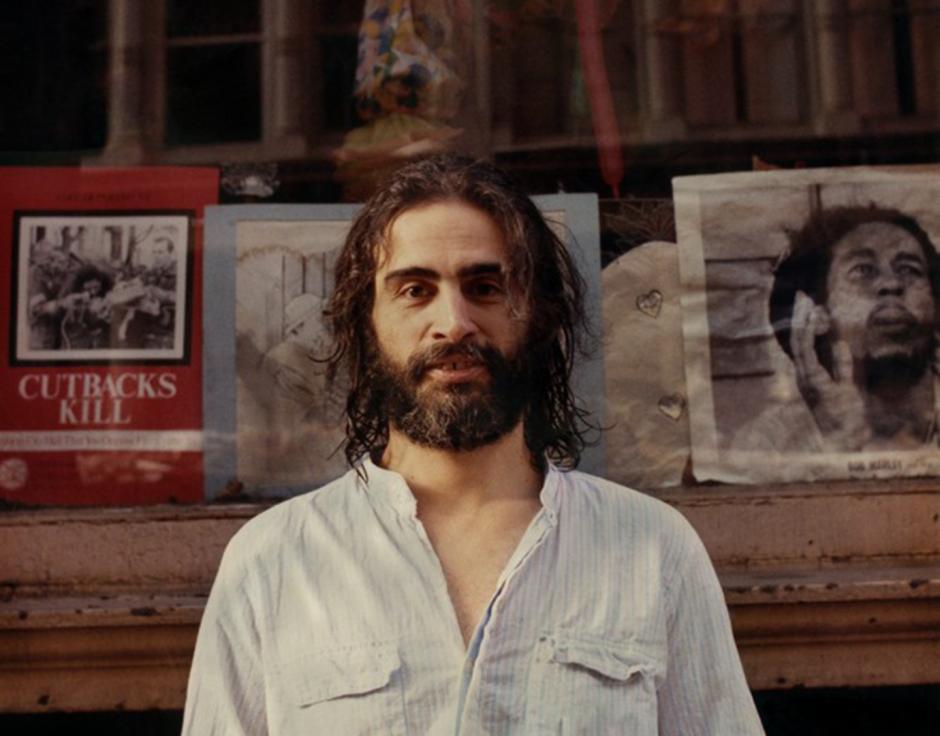

David Mancuso outside Prince Street Loft, New York, 1988. Photo by Pat Bates

When David Mancuso passed away on November 14, 2016, he left behind a legacy that enjoys no obvious precedent. Celebrating the Loft’s 46th anniversary this past February, he oversaw what must surely be the longest-running party in the United States’shistory—and perhaps even the world’s—having hit upon the right combination the night he staged a “Love Saves the Day” Valentine’s party in his downtown home in 1970 and initiated Loft-style parties in Japan and London 16 and 13 years ago, respectively. With all three manifestations rooted in friendship, inclusivity, community, participation, and collective transformation, the host has secured the life-after-death future of the party while demonstrating the effectiveness of a simple vision, the purity of which he never knowingly compromised. In this manner, the Loft has come to offer consistent light to a darkening terrain.

In one of the numerous interviews I conducted with David, I once asked him to explain how he would advise a newcomer to start a party. First, he replied, it’s necessary to have a group of friends that want to get together and dance, because without that there’s no basis for the party. Second, the friends need to find a room that has good acoustics and is comfortable for dancing, which means it should have rectangular dimensions, a reasonably high ceiling, a nice wooden floor, and a level of privacy that will enable people to relax. Next, the friends should piece together a simple, clean, and warm sound system that can be played at around 100 dB (so that people’s ears don’t become tired or even damaged). After that, the friends should decorate the room with balloons and a mirror ball, offering a cheap and timeless solution. They should also plan to prepare a spread of healthy food in case dancers become hungry during the course of the night. Finally—and as far as David was concerned, this was really the last thing to put in place—the friends should think of someone to select records that those gathered would want to dance to. Ultimately there could be no room for egos, including his own, if the party was to reach its communal potential.

Also rooted in friendship and the desire to party with freedom in a comfortable, private space, the Loft—as David’s guests came to name the party after it had been running for a few months—didn’t amount to an original moment so much as it pointed to a time when a number of practices, some of them decades’s old, came together in a new combination. The children’s home where David was taken days after his birth imbued him with the idea that families could be extended yet intimate, unified yet different, and precarious yet strong. Sister Alicia, who took care of him, put on a party whenever she was able to, and even went out to buy vinyl to make sure the kids were musically fed. The psychedelic guru Timothy Leary, who invited David to his house parties and popularized a philosophy around the psychedelic experience that would inform the way records came to be selected at the Loft, also became a power echo in David’s party scenario. Co-existing with Leary, the civil rights, gay liberation, feminist, and the anti-war movements came to manifest themselves in the egalitarian, rainbow coalition, come-as-you-are ethos of the Loft. And the Harlem rent parties of the 20s, in which working-class African Americans put on shindigs in order to raise money to pay the rent, established a template for putting on an intimate private party that could bypass the restrictions of New York City’s widely loathed cabaret licensing regulations. These streams travelled in different directions until February 14, 1970—when they met at 647 Broadway.

The homemade invitations for the February party carried the line “Love Saves the Day.” A short three years after the release of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” the coded promise of acid-inspired things to come swapped The Beatles’ gobbledygook with a declaration of universal love. The invitations also reproduced an image of Salvador Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory,” which suggested not Sister Alicia nor the children’s home—because David had yet to have his latent memories jogged into revelation—but instead, the chance to escape violence and oppression by entering into a different temporal dimension in which everyone could leave behind their socialised selves and dance until dawn. “Once you walked into the Loft, you were cut off from the outside world,” explained David. “You got into a timeless, mindless state. There was actually a clock in the back room but it only had one hand. It was made out of wood and after a short while it stopped working.”

When David’s guests left the Valentine’s Day party, they let him know that they wanted him to put on another one soon, and within a matter of months the shindigs had become a weekly affair. Inasmuch as anyone knew about them—and few did, because David didn’t advertise his parties, because they were private—they acquired a reputation for being ultra hip, in part because 647 Broadway was situated in the ex-manufacturing district of downtown New York, where nobody but a handful of artists and bohemians had thought about living. The artists (and David) moved in, because the district’s old warehouses offered a spectacular space in which to live as well as put on parties, and the inconvenience of having to have one’s kitchen, bedroom, and bathroom hidden from view (in order to avoid the punitive eyes of the city’s building inspectors) turned out to be a nice way to free up space in order to do things that weren’t related to cooking, sleeping, and washing. Outside, the frisson of transgression was heightened by the fact that there was no street lighting to illuminate the cobbled streets, and because David didn’t serve alcohol, he was able to keep his parties going until midday (and sometimes later), long after the city’s bars and discotheques had closed for the night. “Because I lived in a loft building, people started to say that they were going to the Loft,” remembered David. “It’s a given name and is sacred.”

From the beginning, David constantly sought to improve his sound system, convinced that this would result in a more musical and therefore a more socially transformative party experience. Having begun to invest in audiophile technology, he asked sound engineers to help him build gear, including tweeter arrays and bass reinforcements, so that he could tweak the sound during the course of a party, sending extra shivers down the spines of his guests. Yet by the time the technology had come to dominate discotheque sound, David had concluded that such add-ons were unnecessary with an audiophile set-up and instead headed deeper into the world of esoteric stereo equipment, adding Mark Levinson amplifiers and handcrafted Koetsu cartridges to a set-up that also featured Klipschorn speakers. “I had the tweeters installed to put highs into records that were too muddy but they turned into a monster,” David once said to me. “It was done out of ignorance. I wasn’t aware of Class-A sound, where the sound is more open and everything comes out.”

As David relentlessly fine-tuned his set-up, the energy at his parties became more free flowing and intense. “You could be on the dance floor and the most beautiful woman that you had ever seen in your life would come and dance right on top of you,” Frankie Knuckles, a regular at the Broadway Loft, once commented in an interview. “Then the minute you turned around, a man that looked just as good would do the same thing. Or you would be sandwiched between the two of them, or between two women, or between two men, and you would feel completely comfortable.” Facilitating a sonic trail that was generated by everyone in the room, David would pick out long, twisting tracks such as Eddie Kendricks’s “Girl, You Need A Change of Mind” and War’s “City, Country, City,” gutsy, political songs like The Equals’s “Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys” and Willie Hutch’s “Brother’s Gonna Work It Out,” uplifting, joyful anthems such as Dorothy Morrison’s “Rain” and MSFB’s “Love Is the Message,” and earthy, funky recordings that included James Brown’s “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” and Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa.” Positive, emotional, and transcendental, these and other songs touched the soul and helped forge a community.

The influence of the Loft spread far and wide. At the end of 1972, a Broadway regular opened the Tenth Floor as a Loft-style party for an exclusive, white gay clientele, which in turn led to the opening of Flamingo, which went on to become the most influential venue in the white gay scene. Objecting to the elitist nature of Flamingo’s self-anointed “A-list” dancers, another Loft regular founded 12 West with the idea of creating a more laidback party environment for white gay men. Meanwhile Nicky Siano, another Loft regular, launched his own Loft-style venue called the Gallery that mimicked David’s invitation system, hired his sound engineer, and even borrowed a fair chunk of his crowd when he shut down his party for the summer of 1973. The Soho Place (set up by Richard Long and Mike Stone) and Reade Street (established by Michael Brody) also drew heavily on David’s template. When both of those parties were forced to close, Brody resolved to open the Paradise Garage as an “expanded version of the Loft” and invited Long, considered by many to be New York’s premier sound engineer, to build the sound system. Meanwhile Robert Williams, another Loft regular, opened the Warehouse as yet another Loft-style venue after moving to Chicago. Heading to the Loft, where they danced and bonded, Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles went on to become the path breaking DJs at the Garage and the Warehouse, where they forged the outlines of what would later be called garage and house music. Other influential dance figures, including Tony Humphries, François Kevorkian, and David Morales, would look back on the Loft as an inspirational party. In short, the Loft was an incubator.

Like any party host, David had to face some unexpected hitches during his party’s 46-year run. In June of 1974, he moved to 99 Prince Street after city regulators pressured him into leaving his Broadway home. Ten years later, he bought a promising building in Alphabet City, only to see the neighbourhood slide into a virtual civil war. By the time he was forced to vacate a floor he was subletting on Avenue B towards the end of the 90s, things were beginning to look quite grim. But before he was forced to leave Avenue B, David received an invitation to travel to Japan, and although he was reluctant to put on a party outside his home, he ended up travelling on the basis that it could help him purchase the Avenue B space. Unfortunately, the purchase never came to pass. David returned to Japan to put on regular parties with a new friend he made during his initial trip, and he also started to put on parties with friends in London after he approached me and Colleen with the idea while “Love Saves the Day”—the book that charts his influence—was going through production.

As he went about putting on these parties, David stuck to the principles that have driven him from day one: stay faithful to your friends, find a good space for the events, get hold of the best sound equipment available, and smile when people welcome you as a guest. In the process, David drew on the life shaping experience of his orphan childhood to realize a profound philosophical lesson: homes can be built wherever you put down roots and make friends. Returning again and again to Japan and London, David realized his own universal vision, which was previously constricted to New York, but has now captured the imagination of partygoers across the globe.

Shortly after making his first trips to Japan and London, David hit upon a hall in the East Village that became the new home of the Loft, and though the parties were held on holidays rather than a weekly basis, David was convinced the dance floor that remained was as vibrant and energetic as ever. The fact David didn’t live in the space was a little inconvenient in that, with the help of friends, he had to set up his sound system each time he played, but even though he didn’t sleep in the hall, he was more comfortable in that space than any of his previous homes. “It’s in the heart of the East Village, which was where I always used to hang out,” he said. “I might have lived on Broadway, but for the other five or six days I was in the East Village. This is where I’ve been hanging out in the area since 1963. My roots are there. My life is connected to the area.” Forging new roots and connections, grandparents started to dance with their grandchildren on the floor of the New York Loft.

Thanks to David’s overdue recognition as an underpinning figure in the history of New York dance, it has become easy for partygoers to assume that the Loft has come to resemble a nostalgia trip for the halcyon days of the 70s and early 80s. Since February of 1970, however, David always mixed new and less new, even old, music, and he maintained the mix right to his final turns as a musical host. New faces in Japan and London might have arrived expecting a trip down disco alley, but that’s not what they got with David, because the party never became a fossil. Throughout, David remained committed to selecting records that encouraged the party to grow as a musically radical and diverse community. This sonic tapestry could sometimes sound strange to dancers who had become accustomed to a political climate in which communities were so casually displaced by materialistic individualism and nationalistic war, but the countercultural message was always powerful. “After a while, the positive vibe and universal attitude of the music was too much for me, but this moment of hesitation and insecurity only lasted for a few minutes,” commented a dancer following one party. “Then all the barriers broke and I reached the other side. Like a child, I stopped caring about what other people might think and reached my essence, through dancing.”

Confronted by the tendency of dancers to worship him—even though he never thought of himself as being a DJ, and was resolute in his belief that this kind of attention detracts from the party—David positioned his turntables so that partygoers would see the dance floor, and not the booth, as they entered the room. In a similar move, he also arranged his speakers so they would draw dancers away from the booth and towards the center of the floor. Admittedly in London (much more so than in New York), dancers tended to face David all the same, even though the effect was the equivalent of sitting with one’s back to musicians during a concert. At the end, dancers would applaud him as if in the presence of saviour, when he preferred to see himself as the co-host of a party whose job it was, when positioned behind the turntables, to read the mood of the dance floor. Reinforced by popular culture, which encourages crowds to seek out iconic, authoritative, supernatural leaders, the adulation made David feel deeply uncomfortable. “I’m a background person,” he noted.

Even if utopias can’t be built without a struggle, and can never be complete, the mood at the London parties was thrilling to behold during David’s visits and, in the ultimate test of his anti-ego philosophy, remained powerful after he stopped travelling on doctor’s orders. While some endowed David with a halo, a significant counter-group related to him as a friend, and the continuation of the applause in-between records and at the end of a party—when Colleen Murphy along with Simon Halpin/Guillaume Chottin picked up musical hosting responsibilities—suggested David’s argument that it was directed towards the music rather than him might be correct.

Ultimately, the party revolved around the simple idea of friends and friends of friends wanting to dance together in a comfortable and contained setting, with the music piping through clean, warm audiophile equipment, and a little talc helping participants get into the musical journey. David had indeed started the parties in London through friendship and during his time never once worked with an alternative set-up on the basis that one should stick with one’s friends. These foundations came to define the events. “It’s unbelievable,” one female dancer told me after her first party. “The people here—they make eye contact!”

David was all about contact. When he travelled to London, he was ready to accept a lower fee in order to be able to spend five nights in a hotel, not because he wanted to live it up but because he wanted to be in the city before and after each party so that he could build relationships—relationships that would feed back into the party and through the party back into the cosmos. This way of being imbued the way David related to strangers he’d meet who had nothing to do with the party. Whether we were going into a shop to buy groceries or visiting a hi-fi company to check out equipment or heading to his hotel at the end of a party, he invariably engaged with strangers as if they were all potential friends. He loved the telephone as a form of communication and for a while he was heavily drawn to the connections made possible via the Internet. Ultimately, however, he believed in the higher plane of the party.

Relationships built over a lifetime burst forth in the hours and days that followed David’s passing. Many knew David personally and spoke of him in the warmest possible terms. Others came forward as participants in a party who knew that they had entered into a nurturing environment in which social bonding and transformation were never compromised. It meant that David could live on in the knowledge that he had brought joy and hope to an incalculable number of people. “I don't want to go into the ‘I won’t always be here’ thing, but if I’m not here tomorrow, we now know what to do and what not to do,” he told me during a 2007 interview. That has come to pass as three parties in three cities in three countries in three continents are totally set to carry forward the Loft tradition in its remarkably pure form.

During dark times the Loft provided light and it will continue to do so. David understood the communal underpinnings of the party and its relationship to the universe like nobody else I ever met. Let us hang onto his words, his insights and his practice. In deepest grief, gratitude and joy, David, love is and will remain the message, music is and will remain love, love saves and will continue to save the day.

This essay is an adaptation of a 2007 article originally written for Placed. The magazine folded before the issue was published. Tim Lawrence is the author of "Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture (1970-79)," "Hold On to Your Dream: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-92," and the newly published "Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-83." He is also a founding member of Lucky Cloud Sound System, which started to put on parties with David Mancuso in London in June 2003.

David Mancuso outside Prince Street Loft, New York, 1988. Photo by Pat Bates

Disco historian Tim Lawrence, author of Love Saves The Day, remembers the late party purist's selection policy at parties in New York, London and Sapporo

David Mancuso made an incomparably profound contribution to the development of contemporary party culture. His vision was the simplest one he or anyone who knew him could imagine, and it inspired many. Yet as the culture stretched out his vision of the role of music within party culture went through turns and somersaults, a number of which took it to the point where it was barely recognisable to Mancuso. In ways that could seem dogmatic yet ultimately resonate as being profoundly ethical, insightful and even mystical, he barely wavered from his original vision during an unprecedented run that dates back to Valentine’s Day 1970. Inevitably he made some false turns as he made his way, yet any deviation only led him back to a path already established. When he passed away a week ago he left a legacy that was almost monk-like in its purity.

Mancuso’s musical philosophy placed music as a central component in a universe that in essence amounts to an unfolding party. Shaped through experiences that ranged from growing up in a children’s home to participating in the kaleidoscopic energies of the countercultural movement, he began to host private parties that combined the Harlem rent party tradition, audiophile stereo equipment, Timothy Leary’s LSD gatherings and downtown loft living with music capable of providing a form of life energy to enable his social gatherings to go further in their journey towards communal-transcendental transformation. Not even Francis Grasso, whose work at The Sanctuary paralleled Mancuso’s early efforts, was this far advanced. And Mancuso was only just starting out.

Prior to Mancuso, DJs were paid to “work the bar”, or whip crowds into a hurried frenzy before “killing the floor” with a slow number that contained the subliminal lyrics “It’s time to drink now”. There was no conversation, no flow. But Mancuso went about his work in the privacy of his own home, not a public space, and with alcohol set aside for the kind of stimulant whose initials inspired him to write “Love Saves the Day” on invitations to his February 1970 gathering, he was able to select music in relation to the energy of his dancing guests. The result amounted to a form of collective, democratic, participatory, improvised music making that was rooted in antiphonal conversation rather than virtuoso monologue. The practice of dancing to pre-recorded music had taken a great leap forward and there could be no shuffling back.

From that night onwards, Mancuso introduced an improbably wide range of sounds into the New York City party scene, with selections such as War’s “City, Country, City” , Chicago’s “I’m A Man” , Eddie Kendricks’s “Girl You Need A Change Of Mind” and Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa” becoming elements in a sonic tapestry that wove in Latin, African, rock, gospel, breakbeat and even country while prioritising explorative records that reached dramatic crescendos. The discovery that long records enabled the party to enter into a deeper socio-psychic plane spearheaded a collective desire that culminated in the innovation of the 12" single. Meanwhile Mancuso placed records on the turntable according to the signs and signals of his dancing guests, conscious that a ‘third ear’ combining the consciousness of everyone gathered would ultimate lead to a journey that loosely followed the three bardos of intensity outlined by Leary in his notes on the acid experience.

The practice of mixing between two records – a technique pioneered by Grasso at the Sanctuary – seemed somewhat insignificant within the context of The Loft, as guests came to name Mancuso’s parties. Instead Mancuso remained more interested in the way records could be knitted together according to instrumental signatures, lyrical themes, production values and energy patterns to form an unfolding journey that by the early 1980s could last for up to 18 hours. The means of segueing from one record to another was just a technical matter that shouldn’t become more important than the music itself.

Mancuso related to music within an ethical framework that sought to bring social progress to the world, albeit on a local level. He co-founded the first record pool, the New York City Record Pool, in order to help his peers receive free copies of records to play/promote without record company support. He refused to play bootlegs on the basis that the original artists wouldn’t get their share of the sale. He declined to speak of his music selections or his playlists, preferring to attribute everything to the collective endeavour of The Loft. When asked about his approach to playing records, he’d wonder about the premise of the question because the truth of the matter was he couldn’t even play a musical instrument. He kept sound levels to 100dB because anything louder might damage the ears of one of his guests, and why would he want to harm someone entering a social situation?