Edited from ‘Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology’, written for the Journal of Popular Music Studies.

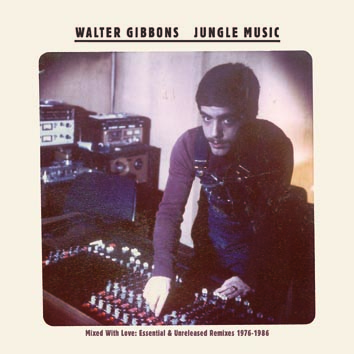

Walter Gibbons stood at five foot five, sported a wispy moustache, and parted his brown hair right to left. He was also shy and softly spoken. He worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the 12-inch single, characterised the synergy that ran between the dancefloor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time that DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their skills to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.

Born in Brooklyn on 2 April 1954, Gibbons started to forge his sensibility at a young age. At the Walt Whitman Junior High in Brooklyn, recalls one friend, "he was the lone white boy hangin' out with the sistahs… a fairly tough group of black girls" who probably "helped cultivate his musical taste," and by June 1972, when he met Rich Flores on a Gay Pride event, he had accumulated a collection of 1,500 seven-inch singles. Soon after this, Flores visited Gibbons and witnessed him play records on an amp and two Gerrard turntables. "He had two copies of Bobby Byrd 'Hot Pants', and he extended the opening of the record by using headphones and the fader. He could keep it going for as long as he wanted. It was easy for him."

Gibbons had already DJed for a month or two at a club called Sanctum Sanctorum but he was more focused on playing at private house parties, where he would set up his home stereo system and sometimes make a little money. "He was green," remarks Flores, who moved into an apartment with Gibbons in the autumn of 1972. "He knew nobody in the industry and he had no connections." That began to change when Gibbons started to work at Melody Song Shops in the spring of 1973 and, towards the end of the year he started to DJ at the Outside Inn, a gay venue situated in Jackson Heights, Queens. When MFSB released ‘Love Is the Message’ around the same time, Gibbons took to extending its instrumental section, after which he began to blend it with spoken extracts from the Wizard of Oz, yet it was his ability to extend the break that became his trademark skill. "I was amazed at the way he would mix," remembers Mark Zimmer, who went to listen to Gibbons after meeting him in Melody Records in early 1974. "He was working with these short little records, which were just two or three minutes long and he had the mixing down pat. It was just magnificent to see him do it."

Gibbons went on to DJ at Galaxy 21, an after-hours venue on 23rd Street, around late 1974 / early 1975, and it was there that he began to play records such as Rare Earth’s ‘Happy Song’, Jermaine Jackson’s ‘Erucu’ and the Cooley High soundtrack number ‘2 Pigs and A Hog’, all of which contained prominent breaks. "Walter was so innovative," notes Kenny Carpenter, who witnessed Gibbons forge his craft at Galaxy 21, where he worked the lights. "He would buy two copies of a record like 'Happy Song' and he would loop the thirty-second conga section." Looping breaks in order to generate tension before switching to a euphoria-inducing vocal crescendo, Gibbons acquired a reputation for being for being a highly skilled original. "Walter was making a lot of flawless mixes," says Danny Krivit. "He would go back and forth, very quickly, which made it sound like a live edit. It was very impressive." According to disco historian Peter Shapiro, people started to refer to the spinner's style as "jungle music".

Many New York DJs were already deploying the technologies of the turntable and the mixer to intensify the experience of the dance floor. Francis Grasso pioneered the art of extended beat mixing, while David Mancuso stuck to rudimentary segueing, focusing on developing themes around lyrical meanings and moods. After that, New York spinners such as Jim Burgess, Bobby "DJ" Guttadaro, Richie Kaczor, Larry Levan, Tee Scott, Nicky Siano and Ray Yeates began to beat-match and even mix with three turntables. Plying their trade in Boston and Philadelphia, John Luongo and David Todd mixed between the breaks of records. Gibbons appreciated the work of his peers: in his opinion, Todd could beat-mix for longer than any other spinner, while Kaczor was "one of the first DJs to do this type of mixing."

Amidst the turntablist frenzy, Gibbons acquired a reputation for championing the break. "The break in 'Happy Song' is only thirty seconds long and he [Gibbons] knew exactly how to make it click because to me it sounded like one record," recalls François Kevorkian, who worked alongside Gibbons at Galaxy 21. "I was playing along with the drums and it was always the same pattern, always the same number of bars. He had this uncanny sense of mixing that was so accurate it was unbelievable." DJ John "Jellybean" Benitez grew up in the South Bronx and witnessed DJs such as Afrika Bambaataa scratch and quick-cut before he went on to hear Gibbons spin at Galaxy 21. "He would cut up records creatively, he would play two together, he did double beats and he worked the sound system," says Jellybean. "Walter played a lot of beats and breaks, and I had never heard a disco DJ playing those kinds of records before. His style appealed to my Bronx sensibilities. He just blew me away."

Disco spinners were also left open-mouthed. "Walter was doing things other DJs wished they could try in their clubs, including me," remembers Tony Smith, the DJ at Barefoot Boy, who became close with Gibbons during this period. "I heard every DJ, straight and gay, because I wanted to know what was going on in the music world. Walter was the most advanced." Having heard the future, Smith started to go to Galaxy 21 on a regular basis once he had wrapped up for the night at Barefoot Boy. "Everyone was going to hear Walter," adds Smith. "Most DJs finished at four so we could hear Walter from five until ten. DJs couldn't go and listen to too many people because we had played all night, but we knew Walter would turn us on. It happened close to overnight. DJs were saying, 'Oh, did you hear Walter?' because no one else was doing it."

Gibbons soon turned to reel-to-reel technology to support his aesthetic while lessening his workload. "There were so many short songs where he had to do this mixing technique that after a while he started to put his beat mixes on reel-to-reel at home," explains Smith. "Walter became really adept at reel-to-reel." Kenny Carpenter remembers that if a mix was well received, Gibbons would also look to perfect it on tape. "Galaxy 21 had a reel-to-reel player/recorder for him to play his edits," notes Carpenter. "He worked in this way to protect the exclusivity of his mixes since, in those days, you couldn't make a copy of a reel-to-reel."

Situated on 47th Street and Broadway, Angel Sound appears to have been the first company to start pressing up dance records onto acetate for club play. According to owner Sandy Sandoval, DJs would enter the studio with reel-to-reels and cassettes that contained looped breaks and other reworked instrumental sections, and they also used the studio to grab non-rhythmic parts (such as speech extracts) and overlay those parts onto other tracks. "They would get these tapes together and they came to us to have the music put onto disc," comments Sandoval. "They were all striving to have something that was a little bit different."

Initially DJs went to Angel Sound with the sole intention of pressing up acetates of rare records, but when Gibbons played Flores two Angel Sound bootlegs Max B's 'Bananaticoco' and 'Nessa', Flores became inquisitive. Discovering that Sandoval charged seven or eight dollars per acetate, he decided to purchase his own record-cutting lathe in order to combine his technical know-how with Gibbons’ impressive record collection. Twenty 45 acetates were eventually pressed up on their label, Melting Pot, by artists ranging from James Brown and Edwin Starr to Exuma and Tony Morgan.

In addition to chasing down rare recordings, Gibbons also "knew how to be a little aggressive" in order to get promotional records, recalls Zimmer. The outlook served Gibbons well when he approached Salsoul, a newly formed independent label, and offered to promote their records for free as long as he did not have to pay for them. Ken Cayre, the co-owner of the company, remembers, "He became friendly with Denise Chatman, our promotions girl, and we went to hear him play. I was very impressed with his skills."

Cayre had already put Salsoul on the map with the release of "Salsoul Hustle," and having released a promotional 12- inch of the 6.50 album version of "Ten Percent" by Double Exposure, which consisted of the standard single plus an extended jam, he witnessed Gibbons work two copies of the promo in his trademark fashion. "He did this fantastic edit and the reaction in the club was phenomenal," recalls Cayre. "I said, 'Can you do that in the studio?' He said he could." Cayre was the first label head to grasp that the 12-inch single would appeal to dancers as well as DJs, and accordingly released ‘Ten Percent’ as the first commercially available 12-inch, commissioning Gibbons to team up with the engineer Bob Blank to produce the remix. They were given just three hours to complete the job. "Walter was prepared but he couldn't prepare everything," says Blank. "He had to be ready to do 'brain work' on the spur of the moment. The session was very intuitive. Walter was a real genius."

Gibbons transformed the album version of ‘Ten Percent’ into a 9.45 roller coaster that stretched out the rhythm section, the strings and T.G. Conway's keyboards, and he started to spin an acetate of his new version in late February/early March 1976. Released in May, the remix captured the way disco's aesthetic was beginning to influence wider music culture. "I heard it in the Gallery," recalls Mixmaster editor Michael Gomes. "It built and built like it would never stop. The dance floor just exploded." Sales of the 12-inch single quickly outstripped the regular 45 by two to one and Cayre understood the significance. "Walter was the first DJ to show the record companies that they should be open to different versions of a song," he notes. "He was pivotal. He convinced producers and other record companies to give the DJs an opportunity to remix records for the clubs. And he showed us that these records could be commercially successful.”

Gibbons remixed ‘Sun… Sun… Sun…’ by Jakki around the same time. Produced by Johnny Melfi and released on Pyramid as a 12-inch in 1976, the record sleeve information contained no reference to Gibbons, but Chatman (who was nicknamed "Sunshine" because of her cheerful personality), remembers a conversation from the time. "Walter called me and said, 'Sunshine, sunshine, sunshine!'" she remembers. "Then he told me the name of the record." The remix consisted of three parts: the regular song (which was released as a 45), a looped break (snatched from the beginning of the B-side of the original 45), and a mix of the A- and B-sides. The break, highly percussive with trippy vocal clips that faded in and out, was typical of the drums-for-days, reel-to-reel edits Gibbons had been perfecting at Galaxy 21. "It was a bad song and Walter turned it into a 9-minute mix," says Smith. "We would just play the break and after a while we grew to like the rest of the song."

Salsoul continued to develop a pivotal affiliation with Gibbons when Cayre invited the DJ to remix ‘Nice 'N' Naasty’ and ‘Salsoul 2001’ by the Salsoul Orchestra. The B-side version of ‘Salsoul 2001’, re-titled ‘Salsoul 3001’, revealed Gibbons' increasing confidence to branch out into more abstract and strange remixes. Opening with jet engines, animal whoops, congas and timbales, the record soared into a powerful combination of orchestral refrains and synthesised sound effects played out against a backdrop of relentless Latin rhythms.

Gibbons developed an even more militant aesthetic on his remix of Loleatta Holloway's ‘Hit and Run’. Released in December 1976 on the Loleatta album, the song appealed to Gibbons, who asked Ken Cayre if he could rework the record. In an unprecedented gesture that demonstrated his faith in the DJ, the Salsoul boss handed Gibbons the multi-track tapes in order to maximise the spinner's creative scope. Previously limited to carrying out cut-and-paste re-edits from half-inch master copies, the Gibbons was now able to select between each individual tracks, and he promptly dissected and reconstructed the album version in a sweeping manner. Discarding large swathes of the original production, Gibbons removed the entire string section and almost all of the horns to place greater emphasis on Ronnie Baker, Norman Harris and Earl Young's rhythm section. Lasting an epic 11.55, the final cut was almost twice the length of the original.

Cayre wondered if he had made a terrible mistake when Gibbons handed him the revised tape. After all, there was no precedent for a remixer to slice out such a high percentage of the instrumentation, not to mention significant elements of the vocal, and the record label boss began to wonder how he would deal with a wrathful Norman Harris, who had produced the record. But the label boss came to realize Gibbons had improved the record from the perspective of the dance floor, and in May 1977 Tom Moulton wrote in Billboard, "This version is really so different from the original that it must be classified as a new record." ‘Hit and Run’ had single-handedly marked out the aesthetic potential of the twelve-inch remix.

While Tom Moulton’s remixes were grounded in melody and structure, Gibbons was drawn to discord and unpredictability, and this approach appealed to dancers and DJs who wanted to be transported into the unfamiliar. "Tom was first and he was consistent all the way through, but Walter's mixes were outrageous and quickly got a lot of attention," says Danny Krivit. "Walter was much more irreverent and became the remixer of the moment." The 12-inch of ‘Hit And Run’ went on to sell approximately 300,000 copies, and marked a further shift in power from the producer to the nascent emergent figure of the remixer. Gibbons now lay at the centre of a transition that would go on to define the DJ-led principles of dance music and hip hop productions throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

During the first half of 1977, Walter Gibbons consolidated his position as the label's most compelling remixer with new versions of records by True Example, Love Committee and Anthony White for Salsoul. During the same period, he also stretched out the Salsoul Orchestra's discordant strings around layers of shifting percussion on his reworking of ‘Magic Bird of Fire’. Yet across the same period Gibbons began to lose control of his special edits, and left Galaxy 21 towards the end of 1976 when he realised his sets were being secretly recorded. Gibbons returned, only to quit again when he discovered that his reel-to-reel edits were being lifted from the booth and pressed up at Sunshine Sound, where Gibbons had separately started to channel the acetate end of his work including a pressing of ‘It's A Better Than Good Time’ by Gladys Knight. "Even though I wasn't with Walter, I spoke with him, and he said Sunshine Sound was secretly recording the DJ mixes while they were cutting their records," adds Flores, whose relationship with Gibbons ended in 1975.

Galaxy 21 closed around the beginning of 1977 and Gibbons spent the next six months bouncing around venues such as Crisco Disco, Fantasia and Pep McGuires. His quick-fire sequence of post-Galaxy 21 residences suggested his challenging playing style and awkward personality made it difficult for him to settle into a regular discotheque. He had already failed to hold down alternate positions at Limelight, Better Days and Barefoot Boy, where he played on his nights off from Galaxy 21. "Walter was too experimental and too creative," reasons Smith. "Most DJs trained their crowd to know them, but Walter was known for being Walter and he didn't want to change.” Kenny Carpenter adds: "The business had changed and it wasn't Walter's era anymore."

Although his DJing career had dipped, Gibbons was by no means history. Even in 1978, the year in which record companies attempted to capitalise on the "craze" that followed the opening of Studio 54 and the release of Saturday Night Fever during 1977, Gibbons picked up plenty of remix commissions, especially from Salsoul, and his reconstructions of Love Committee ‘Law And Order’ and ‘Just As Long As I Got You’ illustrated disco's ongoing potential for aesthetic progressiveness. His irreverence continued to flourish on two relatively obscure 12-inch singles: Cellophane's ‘Super Queen’ and ‘Moon Maiden’ by the Luv You Madly Orchestra, a Duke Ellington song that appeared on the B-side of the more conventional ’Rocket Rock’. The vocals on both tracks resembled what Abba might have sounded like if they had modified their middle European accents with a cocktail of amphetamines, acid and helium, and Gibbons accentuated the effect, intertwining the contorted voices with a series of modulating synths and stabbing strings which he laid over an insistent and shifting bongo-driven beat track.

During the same period Gibbons mixed Loleatta Holloway's ‘Catch Me On the Rebound’, two versions of TC James and the Fist-O-Funk Orchestra’s ‘Get Up On Your Feet (Keep On Dancin')’, Sandy Mercer's ‘Play With Me’, backed with ‘You Are My Love’ and Bettye LaVette's ‘Doin' The Best That I Can’. Co-mixed by the late Steve D'Acquisto, the Mercer release was noteworthy for its B-side, which became a favourite of Ron Hardy (who would go on to pioneer house music in Chicago) and Larry Levan (the DJ at the legendary Paradise Garage). Meanwhile the epic eleven-minute remix of 'Doin' The Best' shuttled between instrumental and vocal sections before setting off on a disorienting, dub-inflected rollercoaster ride of bongos, handclaps, tambourines and instrumental interludes.

Nevertheless towards the end of the year Gibbons began to distance himself from the disco scene when, having come close to completing a remix of Instant Funk ‘I Got My Mind Made Up’ for Ken Cayre, he decided that he didn't want to be associated with the record's flagrantly sexual lyrics, and asked the Salsoul head for the song to be rewritten. When Cayre refused the request, Gibbons agreed that Levan (who had previously remixed just one record) should finish off the job and receive credit for the entire mix. Blank and Chatman both witnessed the deal unfold.

"Walter was starting to get into the Bible and Jesus back in 1974 or 1975," notes Mark Zimmer. "He was always interested in spirituality, and that led him to programme only music that contained positive lyrics, but he also led a gay lifestyle. He thought, 'God is on my side with me when I play this style of music.'" According to Zimmer, Gibbons attended a church that was tolerant of homosexuality, yet as his religious outlook hardened, he became increasingly intolerant of dance culture's liberal relationship with sexual licentiousness and drug consumption, and instead of consolidating his cutting-edge reputation, Gibbons began to distance himself from the club scene. The zealousness he had channelled through his fiery DJing, editing and remixing came to be expressed through sermonising and intolerance. "When Walter went religious he alienated all of his friends," says Kenny Carpenter. "He was really fanatical about the whole thing."

Gibbons continued to impress Blank, who maintains Gibbons was a consummate professional in the recording studio. While most remixers entered unprepared and barked out instructions, Gibbons always did his homework, notes the engineer. Yet the thing that most impressed Blank was the remixer's intuitive style. "It was quite easy to chop up a record and extend certain sections," he says. "The difficult thing was to take a multi-track and create a flow. The skill lies in feeling the music and that's what Walter could do. He would sit at the board with the mute buttons, and he would cut and edit in real time." Gibbons took the art of remixing into the realm of emotion and affect. "He would come in and say, 'I want this song to be the love mix.' That's totally different to someone who comes in and says, 'I've got to get this mix out in a day and we've got to have three breaks!'"

Cayre went on to entrust Gibbons with the task of recording an album of custom-designed 12-inch mixes, and with no contentious lyrics to disturb the production process, Salsoul released Disco Madness in March 1979. "It was the first time a label had released an album of mixes by a single remixer," says Cayre. "Every DJ was inspired by Walter." Including six mixes, the album helped forge a set of sonic principles that would run through the future of post-disco dance music. Aside from the Disco Dub Band's 1976 cover of ‘For The Love Of Money’ and Gibbons’ mix of ‘Doin' The Best That I Can’, the release was the closest disco had come to establishing an aesthetic alliance with dub. The album also contributed to the emergence of house when Frankie Knuckles, who was spinning at the Warehouse in Chicago, turned the remix of First Choice ‘Let No Man Put Asunder’ into one of his signature records. A year or so later, Warehouse dancers started to describe the music they were hearing as "house music", and cited ‘Let No Man’ as the record that was most typical of the sound.

Gibbons completed four more mixes for Salsoul in 1979, including tracks by Double Exposure and the Robin Hooker Band. The treatments sounded like the work of a man who had a gifted feel for dance music, but who had begun to fall out of synch with the culture in which it was played. The deepening disjuncture came to be reflected at Salsoul, where remixes began to be offered to other DJs (most notably Levan) while Gibbons was offered scraps.

Gibbons DJed at the Buttermilk Bottom and Xenon during this period, but his sets became increasingly improbable and his residencies ever more ephemeral. "I got Walter his job at Xenon and the owners complained because he only played gospel and Salsoul," recalls Tony Smith. "I said, 'Walter, you can't do that!' There was so much great music out there at the time. Larry was coming out with all this new stuff. But Walter wouldn't change and after three weeks they told me to fire him." Gibbons was now using a marker pen to blot out any unsavoury words that appeared on his records, as well as highlight any song titles that contained the word "love" with a heart. "His musical horizon shrank," adds Smith. "All of a sudden the music had to have all these big messages and he wouldn't play any negative songs."

Along with a number of other DJs, producers and remixers, Walter Gibbons ignored the market-driven logic that required dance or rap to develop distinctive sounds in order to sell to segmented audiences when he recorded ‘Set It Off’ by Strafe in 1984. The debut release on Jus Born Records, which was co-owned by Gibbons and explicitly referenced his religious affiliation, ‘Set It Off’ featured vocals by Steve "Strafe" Standart, a childhood friend of Kenny Carpenter's. Sparse, atmospheric and heavily syncopated, the twelve-inch maintained the link between the hip hop offshoot of electro and the post-disco continuum of early 1980s dance.

In all likelihood ‘Set It Off’ was played for the first time in 1984 when Gibbons approached Tony Smith at the Funhouse and handed him a test pressing of the record. "Walter had brought the track to other DJs before me but no one would play it," recalls Smith. "Even Strafe didn't like it, or should I say 'understand' it. Ultimately, I played both sides. It cleared the floor." Smith notes that the Funhouse crowd had become attuned to the sound of Arthur Baker's electro, which was more direct and pop-oriented than ‘Set It Off’, but adds that "everyone in the booth was stunned by the record it was so incredible and different."

Smith managed to lay his hands on a copy of ‘Set it Off’ when he discovered the Funhouse light man Ricky Cardona had made a reel-to-reel tape of his set, and he proceeded to play the record once a night until his dancers began to ask after the track. By the time Gibbons returned to the club, ‘Set It Off’ had become a dance floor favourite. "Everyone screamed when I put it on," remembers Smith. "Walter was totally shocked." Jellybean, the principal DJ at the Funhouse, also went heavily on the record and helped build it up into a Funhouse classic. "It was very, very different to everything that was out there," he says. "It had soul, it had electro, it had Latin. It was a long record that took you on a journey. It captured so many different things — and it had just the right energy."

For his second release on Jus Born, ‘I’ve Been Searching’ by Arts & Craft, Gibbons developed live percussion, strings, and soulful vocals within a minimalist structure that evoked a spiritual sensibility. Creating space through its emphasis on low and high-end frequencies, the track would become a reference-point for the followers of so-called deep house, a loosely defined sound that created its effects as much through absence as presence. Yet there was no record industry rush to sign the mix and, left with no choice but to plough his own groove, Gibbons teamed up with Barbara Tucker, then little known gospel vocalist, to produce his next release, a new version of ‘Set It Off’, which he released in 1985 under the moniker Harlequin Fours. "After 'Set It Off', I thought he would get back into the music business," says Smith. "The record went to number one on the dance chart but nobody gave him any offers."

Gibbons recorded two of his final releases with Arthur Russell, the experimental-composer-turned-disco-auteur, who had co-produced ‘Kiss Me Again’ with the Gallery DJ Nicky Siano as Dinosaur in 1978. Russell became interested in Gibbons after hearing his mix of Sandy Mercer's ‘Play With Me’, and the two of them ended up meeting each other for the first time in the offices of West End (the label having signed Russell's Loose Joints project). When Russell heard ‘Set If Off’, he resolved to work with Gibbons. "Strafe changed our lives," reminisces Steven Hall, a musician and close friend of Russell. "It would play in the black gay clubs on the waterfront and people would abandon themselves in a kind of Bacchanalian trance. The record gave Arthur a new idea about how to use trance-like states in dance music." In 1986, Russell invited Gibbons to develop a mix of ‘Let's Go Swimming’, an off-kilter dance track. "Walter created a visionary, psychedelic soundscape for the song," says producer Gary Lucas. "He sort of out-avant-garded Arthur and took the song out to the stratosphere.” Russell also asked Gibbons to bring his leftfield sensibility to bear on ‘School Bell/Treehouse’, released on Sleeping Bag in 1986.

In Gibbons, Russell found an ideal companion with whom he could make quirky, leftfield dance music, and also a friend who, like himself, was intensely creative, softly spoken and unremittingly intense. Will Socolov, who co-founded Sleeping Bag Records with Russell, remembers Gibbons being obsessed with the nuances of musical texture and notes that Russell was the only other person who liked to analyse sound in such microscopic detail. Gibbons remixed 'Go Bang! #5' during scrambled-together hours at Blank Tapes and, although the taut, stretched out result lacked the dramatic dynamism of Kevorkian's tighter earlier remix, his epic version retained the freestyle spirit of the original sessions. Other records, such as the sparse and funky 'C-Thru', remained unfinished. The electronic, twitchy ‘Calling All Kids’ ended up appearing on the posthumous Arthur Russell compilation ‘Calling Out of Context’ in 2004.

Gibbons worked on at least three other records during the mid-1980s in what would turn out to be his twilight period. In 1985, he mixed the promo-only Arts & Craft ‘Wait A Minute "Before You Leave Me"’ and, a year later, ‘Time Out’ by gospel act the Clark Sisters. Gibbons then heard ‘4 Ever My Beat’ by the Brooklyn-based hip hop outfit Stetsasonic. "Walter was crazy for the track and begged to remix it," remembers Audika’s Steve Knutson, then at Tommy Boy. "After weeks of nagging we gave in and paid him one thousand dollars to remix it. What we got back was an unusable track, even though I personally loved it. The group hated it and so did the promotion people." At the request of Tom Silverman, the head of Tommy Boy, Knutson carried out the edit with Rodd Houston to the satisfaction of everyone except for Gibbons. "Walter never forgave me," adds Knutson. "He was very, very angry and for a period of a month or so he would call up and yell at me.”

During this period Gibbons also amassed a 5,000-strong collection of gospel records purchased directly from church congregations in New York. Yet he was still able to connect to the dance scene, and appears to have played a key role in bringing one of the most unusual and popular dance records of the early 1980s to the attention of other DJs. An uplifting gospel record, ‘Stand On the Word’ by the Celestial Choir was recorded in 1982 at the First Baptist Church of Crown Heights in Brooklyn, where it was sold as an independent production. "Walter was a member and lived down the block while I was Minister of Music at the Church," says Phyliss Joubert, the leader of the Celestial Choir. "Without my knowledge or consent, he purchased one of the original records from the church and began his own illegal path of doing whatever he chose to do."

It is impossible to confirm if a devotion to the rousing sound and message of ‘Stand On the Word’ persuaded Gibbons to return to the practice of bootlegging in the belief that the end would justify the means, but it seems likely. How else could the record have found its way into one of the weekly listening sessions the promoter Bobby Shaw held with DJs in his office at Warners every Friday? Present when the record was played to this select group of spinners, Steven Harvey was so enchanted with its innocent vocals (which were sung by children) and stirring instrumentation (led by a gospel piano) he paid a visit to the church, purchased a whole box of the vinyl, and distributed copies to his DJ friends as a "free promo". Within a short space of time, ‘Stand On the Word’ became a favourite at venues such as the Loft and the Paradise Garage, while Harvey remembers hearing Gibbons play two copies of the record at a gay bar where he was spinning on Christopher Street.

Walter Gibbons contracted the AIDS virus sometime during the second half of the 1980s. For a while nobody could tell he was sick because he had always looked slight, but as the disease progressed, there could be no mistaking his condition. "I saw him at Rock & Soul about a year before he passed away," recalls Blank. "He was in terrible shape. He was very thin and had lost a lot of his hair. He looked around and said, 'I just love being in contact with music. This is what I love.'"

In September 1992, Gibbons went on a mini-tour of Japan, where interest in the disco era had been gaining momentum. Mixing classics, house and hip hop with his custom-made mixes, Gibbons received an enthusiastic reception from local DJs and music aficionados, and in between appearances at the Wall (Sapporo) and Yellow (Tokyo) he went to listen to Larry Levan and François Kevorkian play at Gold as part of their Harmony tour. When Gibbons returned to Japan a year later he was skeletal but radiantly happy — so happy that he refused to stop playing when police raided Yellow and ordered it to close. In the end the party was reconvened as a private event, and at the end of the night Gibbons asked to be taken to Hakone, situated in the district of Ashigarashimo. When he saw Mount Fuji he kept uttering, "It's beautiful. It's beautiful!" After that he was whisked to a hot spring to revitalise his tired body.

Gibbons played his final set in New York at Renegayde, a monthly night organised by Joey Llanos and Richard Vasquez. Drawing on Motown, Philly Soul, disco, early eighties dance and contemporary house, the ex-Galaxy spinner took his dancers on a message-oriented journey of devotion and love in which he sequenced his selections according to ambience rather than chronology or genre. The late new York DJ / producer Adam Goldstone admired the way Gibbons created an "uplifting, spiritual and positive atmosphere" without slipping "into religious proselytising or the kind of lazy, saccharine clichés that seem to pass for soulful dance music these days." Having spent his final weeks living in a YMCA, Gibbons died of complications resulting from AIDS on 23 September 1994, aged thirty-eight years old.

Gibbons has subsequently received partial recognition for his work within dance, although that recognition might have been more pronounced had he been an easier person to spend time with from the late 1970s onwards, and also if he had been less unbending in his commitment to aesthetic progressiveness. "Walter was an innovator, but he also had an abstract I don't give a shit approach," notes Kevorkian. "Walter didn't care if anyone danced. […] Walter was conceptually the most advanced, [but] he was also a lonely genius."

Along with Tom Moulton, Gibbons established the basic principles of remix culture, and in a fairly short space of time his innovations were judged to be so important they became routine. "By the time Larry came by I had done a thousand dance records," comments Blank. "I knew what was supposed to happen. I didn't say, 'Oh my God, there's the bass drum!' Nobody had heard the strings all by themselves or the rhythm chopped into these syncopated moments, but once Walter did it people began to understand there was a formula. When the next person came in after Walter, I would bring up all of his good ideas." The cool things are now ubiquitous within dance.

CD 1

1. Jakki – Sun… Sun… Sun… (Walter Gibbons Original 12” Edit) 9.19

Taken from the Pyramid 12” single (PD1002). Composed and Produced by Johnny Melfi. Published by Southern Music Publishing Co. Inc. (ASCAP) Engineered by Edison Youngblood. Recorded at Music Farm Studio, NYC. Edited by Walter Gibbons. P 1976 Pyramid Recording Co. Inc.

2. Double Exposure - Ten Percent (Walter Gibbons 12“ mix) 7.06

Taken from the Salsoul 12” single (12D-2008). Composed by T.G. Conway and Alan Felder. Published by The International Music Network Ltd and Warner Chappell Music Ltd. Produced by Baker, Harris & Young Productions. Disco blending by Walter Gibbons. P 1976 Salsoul Record Corp. Licensed courtesy of Salsoul Records Corp.

3. TC James & The Fist-O-Funk Orchestra - Get Up On Your Feet (Keep On Dancin') (Walter Gibbons 12” mix) 11.11

Taken from the Fist-O-Funk 12” single (FOF-1002). Composed by Joseph Davis. Publishing: Copyright Control. Produced by Kevin and Ulla Misevis. Arranged by T.C. James. Special mix by Walter Gibbons. P 1978 Fist-O-Funk

4. Gladys Knight – It’s A Better Than Good Time (Walter Gibbons acetate mix) 12.21

Taken from the Sunshine Sound acetate. Composed and Produced by Tony Macauley. Published by Macauley Music / Almo Music (ASCAP). Mixed by Walter Gibbons. P 1978 Buddah Records

5. Salsoul Orchestra – Magic Bird Of Fire (Firebird Suite) (Walter Gibbons ‘Disco Madness’ mix) 8.06

Taken from the Salsoul 12” single (SG 500). Composed, Produced, Arranged & Conducted by Vincent Montana, Jr. Published by The International Music Network Ltd and EMI Music Publishing Ltd. Mixed by Walter Gibbons. P 1977 Salsoul Record Corp. Licensed courtesy of Salsoul Records Corp.

6. Sandy Mercer - You Are My Love (12" version) 7.32

Taken from the H&L Records 12” single (HLS-2005). Composed by Landy McNeal, George Pettus and Bob Johnson. Published by Boca Music, Inc. and Raton Songs, Inc. Produced by Landy McNeal. Arranged by Jay Dryer and Landy McNeal. Mixed by Walter Gibbons and Steve D’Acquisto. P 1978 H&L Records Corporation

7. Bettye Lavette - Doin' The Best That I Can (Walter Gibbons 12“ mix) 11.04

Taken from the West End Records 12” single (WES 22113-X). Composed by Mark Sameth. Published by Leeds Music Corp. and Sugar ‘N’ Soul Music (ASCAP). Produced by Eric Matthew and Cory Robbins. Arranged by Eric Matthew. Remixed by Walter Gibbons. P 1978 West End Records. Licensed courtesy of Bug Music

CD 2

1. Dinosaur L – Go Bang (Walter Gibbons mix) 12.24

Previously available on the Traffic Entertainment CD ‘Arthur Russell: The Sleeping Bag Sessions’ (TEG-3319-2). Composed by Arthur Russell. Published by Chrysalis Music Ltd. Produced by Arthur Russell and Will Socolov. Remixed by Walter Gibbons. P 2009 Sleeping Bag / Traffic Entertainment Music Corp. Licensed courtesy of Demon Music Group Ltd.

2. Strafe – Set It Off (Walter Gibbons 12” mix) 9.45

Taken from the Jus’ Born 12” single (JB 001). Composed & Arranged by Steve Standard. Published by Reach Global Music. Produced by George Logios and Steve Standard. Mixed by Walter Gibbons. P 1984 Jus Born Productions. Licensed courtesy of Reach Global Music.

3. Arts & Craft – I’ve Been Searching (Walter Gibbons 12” mix) 9.58

Taken from the Jus’ Born 12” single (JB 002). Composed by Arts & Craft. Publishing: Copyright Control. Produced by George Logios. Lead Vocal by Willie Daniels. Mixed by Walter Gibbons. P 1984 Jus Born Productions. Licensed courtesy of Z Records.

4. Luv You Madly Orchestra – Moon Maiden (12” mix) 8.50

Taken from the Salsoul 12” single (SG 2071). Composed by Duke Ellington. Published by Sony ATV Harmony. Produced and Conceived by Stephen James. Arranged and Conducted by Kermit Moore in conjunction with Stephen James. Mixed by Walter Gibbons. P 1978 Salsoul Records Corp. Licensed courtesy of Salsoul Records Corp.

5. Stetsasonic - 4 Ever My Beat (Beat Bongo mix) 6.54

Taken from the Tommy Boy 12” single (TB 897). Written by Glen Bolton, Arnold Hamilton, Paul Huston, Martin Nemley, Leonardo Roman and Shahid Wright. Published by Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp. Produced by Stetsasonic. Mixed with love by Walter Gibbons. Edited by Rodd Houston and Steve Knutson. P 1986 Tommy Boy Music. ISRC: US-TB1-03-00873 / LC: 09173. Licensed courtesy of WARNER MUSIC Group Germany Holding GmbH – a Warner Music Group Company

6. Harlequin Fours – Set It Off (US 12" version) 5.51

Taken from the Jus’ Born 12” single (JB 003). Composed by Steve Standard. Published by Reach Global Music. Arranged by Craig Peyton. Lead Vocals by Barbara Tucker. Vocals Arranged by Willie Daniels. Produced by George Logios. Mixed by Walter Gibbons. P 1984 Jus Born Productions. Licensed courtesy of Reach Global Music.

7. Arthur Russell – Calling All Kids (Walter Gibbons mix)

Taken from the Audika Records CD ‘Calling Out Of Context’ (AU-1001-2). Words and music by Charles Arthur Russell Jr. Published by Echo and Feedback Newsletter (ASCAP) administered by Another Audika (ASCAP) for North America and Domino Publishing Co. Ltd (PRS) for the Rest Of The World. Produced by Arthur Russell. Remixed with love by Walter Gibbons. P 2004 Audika Records LLC under exclusive licence from the estate of Arthur Russell. Licensed courtesy of Audika Records and Rough Trade Records Ltd.

Compiled by Quinton Scott with thanks to Bill Brewster, Dave Hill, Colin Gate, Steve Knutson and Tom Lee

Tim Lawrence thanks: Bob Blank, Kenny Carpenter, Ken Cayre, Denise Chatman, Rich Flores, Adam Goldstone, Michael Gomes, Steven Hall, Steven Harvey, Jellybean, Phyliss Joubert, François Kevorkian, Steve Knutson, Danny Krivit, Gary Lucas, Sandy Sandoval, Tony Smith, Will Socolov, Mark Zimmer, and Quinton Scott.

Dowload the article here.