Although its influence has fluctuated in recent decades, New York City occupied the epicenter of progressive party culture during the 1970s and 1980s. It did so for a reason. Back then, the city was the home to what must have been the most diverse mix of people on the planet, many of them viewed as outsiders, misfits and outcasts by mainstream society. As the postwar boom ran into the ground, and as fresh waves of immigration led many white middle-class residents to head to the suburbs, the city went through a transformation as industrial warehouses emptied out and large parts of the East Village became unoccupied.

In other words, the ideal petri dish for new venues to grow within. The result was a set of spaces that were rough around the edges and nowhere near pristine, yet perfectly imperfect for these exact same reasons.

It was against this backdrop of economic decline and social marginalisation that a coalition of queers, women, African Americans, bohemians and countercultural activists started to innovate forms of community-based partying. Led by the music and the dance, this put civil rights, gay liberation, feminist and anti-war principles into action.

At the same time, artists and musicians gravitated to the city’s semi-abandoned downtown terrain, drawn by the cheap cost of living and the chance to collaborate with peers, and combined to produce a cultural renaissance of epic proportions. The maelstrom resulted in the groundbreaking sounds of disco, punk and hip hop. It also produced a series of parties that cultivated these sounds; and provided participants with new ways of experiencing music, community and ultimately the world in the process.

Welcome to a period in the life of New York City when the margins seized the center.

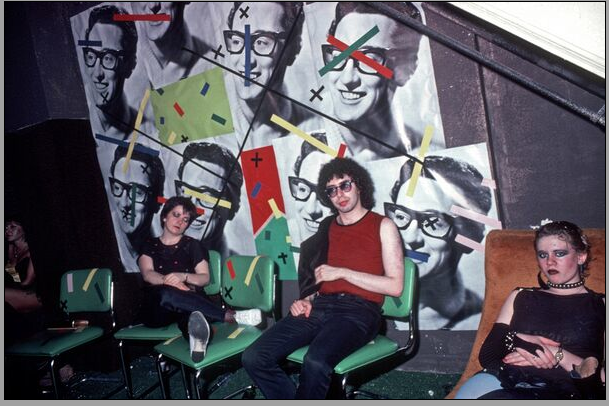

THE MUDD CLUB

Downtown scenesters Diego Cortez and Anya Phillips were diehard regulars at CBGB, but also wanted to be able to head to a spot where it would be possible to dance to something other than disco – and CBGB didn’t have a dance floor. They put the idea of opening a punk discotheque with art-oriented add-ons to Steve Mass, a businessman who also happened to be a CBGB regular. Mass ran with the idea, settling on a dilapidated textile warehouse located on the border of industrial China Town — the last place artists would have expected to find a cutting-edge artist hangout. Opening the Mudd Club on Halloween 1978, Mass curated a whirlwind programme that included DJing, live music, video and film screenings, and Situationist-style happenings. Klaus Nomi, Debby Harry, Chris Stein, Patti Astor, Arto Lindsay, John Lurie, Andy Warhol, Amos Poe, Anna Sui, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Fab 5 Freddy and scores of others turned it into a restless hub for subterranean creativity and outré dancing.

THE LOFT

Starting out as a “Love Saves the Day” party held by David Mancuso in his NoHo loft space on Valentine’s Day 1970, the Loft tore up the rulebook of 1960s discotheque culture. Fuelled by LSD, a definitively mixed crowd that included a significant proportion of gay men, an audiophile stereo system and an expansive range of music that complemented the three bardos of the acid trip, the Loft was the first weekly party to run into the early hours of the morning, long after licensed venues were required to close. The combination enabled Mancuso and his crowd to enter into a uniquely sensitized and energetic communicative plane that – in tandem with Francis Grasso’s efforts at the Sanctuary – inspired the rise of contemporary DJ culture, or the practice that requires DJs to respond to, as well as lead their crowds. Future DJ legends Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles were regulars on the dance floor.

THE ROXY

Bronx-style party culture percolated away in relative isolation during the 1970s, with Disco Fever the primary location for its DJs and MCs. Graffiti unfolded as a largely separate phenomenon and while even breaking (one of a number of styles popular with Bronx dancers) started to fade as the decade disappeared. But then downtown scenesters Fab 5 Freddy and Charlie Ahearn decided to make a film that conceptualised the “four elements” as forming a cohesive thing called hip-hop. Around the same time, Malcolm McLaren employee Ruza Blue turned over her reggae night at Negril to Bronx performers, including Afrika Bambaataa. When the fire department closed the spot, Blue took her party to the Roxy, a gargantuan rollerskating rink. There was no reason to believe the move would work but Blue’s party soon started to attract “a big mash-up of b-boys, downtown trendies, punks, famous people, musicians, painters, gays, trannies — everything you can think of,” she remembers. Hip-hop was gathering momentum in a city where all things hybrid, inclusive and dynamic seemed possible.

DANCETERIA

Drawing on the city’s art-punk, fashion, dance and experimental traditions, gay liberation activist Jim Fouratt and professional hedonist Rudolf Piper opened Danceteria on 37th Street in the spring of 1980 as the first location where partygoers could experience everything at once. One floor showcased cutting-edge bands, another meshed together the contrasting selections of punk DJ Sean Cassette and disco DJ Mark Kamins, and a third housed the city’s first dedicated video lounge. Fouratt curated performers who combined the avant-garde and the popular, mindful that participants needed to be “open to a range of experiences.” Piper focused on interior design, special parties, social engineering and building a staff team that included artists Keith Haring and David Wojnarowicz. Authorities closed the after-hours spot some six months after opening but a new form of partying had come into being. Fouratt and Piper would return.

PYRAMID

Drag queens tended to head to specific drag bars and above all drag balls until Bobby Bradley and Alan Mace took over a struggling spot called the Pyramid Cocktail Lounge. Located on the outer edges of Alphabet City, which rivalled the Bronx for poverty, the setting enabled the owners to cultivate a form of community-oriented partying that offered anti-clone queers the chance to dance to new wave and participate in the wilder end of alternative performance. Even if they formed a minority within the venue’s diverse East Village crowd, larger-than-life drag queens danced on the bar and ran the door, instilling the venue with acerbic wit, radical politics and unfiltered emotion.

Paradise Garage

Inspired by the Loft, Michael Brody ran a private party in an old egg and butter storage plant on Reade Street in TriBeCa until authorities closed the spot for breaching an array of fire regulations. Aware that Mancuso had re-opened in a larger space in SoHo, and convinced a market existed for an even larger version of the Loft, Brody took out a lease on a gargantuan parking garage located on King Street. As it happens the building’s acoustics were terrible while the idea of dancing in a garage wasn’t immediately appealing, but Brody embraced the tension by naming his spot the Paradise Garage and set about turning the venue into the ultimate shrine for all-night dancing. It was here that Larry Levan established himself as the most influential DJ and remixer of his generation--and perhaps any generation.

This article originally appeared on Boiler Room. Click here for the original article.