Disco

Coined to describe the broad range of danceable music played by disc jockeys in public discotheques and private parties in North America in the early 1970s, disco became a recognised genre of uptempo popular music that drew on elements of funk, gospel, jazz and soul. Disco recordings were often built on a propulsive underlying rhythm section, around which a wide range of instrumental and vocal techniques were developed, with structured songs and groove-oriented tracks both prominent. DJs became central to the popularisation of disco records, which were often characterised by the way engineers, producers and remixers deployed a series of increasingly unconventional studio techniques to manipulate vocal and instrumental takes, and the genre peaked commercially in 1978. The subsequent coincidence of disco's industrial overproduction with a deep recession culminated in a backlash against the genre and its associated culture, and during 1980 the music industry stopped using the word "disco" altogether. Although many aspects of disco could be detected in the newly coined category of "dance", as well as later genres such hip hop, house and techno, the increasingly electronic and sequenced character of these sounds also distinguished them from disco.

Emergence of disco and the role of the DJ

The practice of dancing to pre-recorded music in the United States can be traced to the spread of jukebox technology in the 1930s and record hop culture in the 1950s. Parallel practices unfolded in Germany, where "Swing Kids" set up gramophones in order to dance to jazz, and also in France, where the venues that played pre-recorded music became known as "discothèques". Having operated as a space in which resistance fighters would socialise and dance, French discothèque culture acquired an elitist, bourgeois cachet during the postwar era, and this was the version of the culture that travelled to New York when Oliver Coquelin opened Le Club at the beginning of the 1960s. In New York, discotheque culture became more democratic when Arthur, drawing inspiration from London's Ad Lib nightclub, opened in 1965, and a clientele made up of young white heterosexual workers danced the twist. But towards the end of the decade New York's discotheques entered a period of commercial decline, and when Arthur closed in 1969 the media reported that the novelty of the discotheque had worn off.

David Mancuso inside the Prince Street Loft. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery. Photography by Peter Hujar. Copyright Estate of Peter Hujar.

A pivotal turning point for the culture arrived at the beginning of 1970 when David Mancuso, a resident of the NoHo district of New York, put on the first of a series of highly influential private parties that soon became known as the Loft, while two gay entrepreneurs called Seymour and Shelley took over a failing discotheque called the Sanctuary and marketed the venue to the gay clientele who frequented their bars in New York's West Village. Marked by the spirit of the countercultural era, the Loft and the Sanctuary attracted crowds that were mixed in terms of race, gender and sexuality, and the marginalised social status of many of their dancers combined with the popularisation of stimulants such as LSD contributed to the both emergence of a new dynamic on the dance floor and a non-normative way of experiencing the body. Instead of dancing in couples, participants adopted a freeform style that enabled them to dance with the wider crowd, and responding to the increase in energy, Mancuso and Sanctuary DJ Francis Grasso developed a dialogic relationship with their dancers in which they didn't just "lead" but also attempted to "follow" the dancers in their selections. Growing out of Harlem's rent party tradition, the Loft inspired a series of private parties, most of which opened in the recently evacuated industrial buildings of downtown New York, including the Tenth Floor, Gallery, Flamingo, SoHo Place, 12 West, Reade Street and the Paradise Garage. In a parallel development, public discotheques such as Better Days, Hollywood, the Ice Palace, Le Jardin, Limelight and the Sandpiper were structured according to the model of the Sanctuary. In contrast to the largely unregulated private party network, the public discotheques were bound by New York City's Cabaret Licensing legislation.

Between 1970 and 1973 private party and public discotheque DJs were required to search hard for their music, as record companies were unaware of the nascent dance market and appropriate tracks were in short supply. Drawing on funk, soul and rock as well as rare imports, DJ selections reflected the diversity of their dance crowds, and also contained elements of what would become disco. The break featured not once but twice in Eddie Kendricks' "Girl, You Need A Chance of Mind"; the Temptations' "Law of the Land" accentuated the power of the disciplinary beat; Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes "The Love I Lost" called attention to the four-on-the-floor bass beat; the funk alternative, which became prominent in disco, ran through James Brown "Give It Up or Turnit A Loose"; Chakachas "Jungle Fever" included Latin percussion and clipped, sensual vocals; the parallel move of developing politicised lyrics was evident in the Equals' "Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys"; Olatunji's "Jin-Go-Lo-Ba (Drums of Passion)" foregrounded African derived rhythms and chants; swooping orchestration was a hallmark of Isaac Hayes' "Theme From Shaft"; WAR's "City, Country, City" revealed the dance floor preference for long records; an ecstatic gospel aesthetic was integral to Dorothy Morrison's "Rain"; emotional expressiveness ran through the Intruders' "I'll Always Love My Mama" and Patti Jo's "Make Me Believe in You"; and Chicago's "I'm A Man" demonstrated an openness to danceable rock. In September 1973 Vince Aletti published an article titled "Discotheque Rock '72 [sic]: Paaaaarty!" in Rolling Stone that drew attention to the way in which the records that were being played on New York's dance floors tended to feature these recurring traits.

Entering an industry dominated by radio DJs, private party and discotheque DJs demonstrated their ability to promote and sell records when Alfie Davison and David Mancuso became the first spinners to play the import single "Soul Makossa" by Manu Dibango, which subsequently entered the Billboard Hot 100 before receiving radio airplay. The new breed of DJs reiterated their rising influence when they helped transform neglected singles such as "Never Can Say Goodbye" by Gloria Gaynor and "Love's Theme" by the Love Unlimited Orchestra into chart hits. Having functioned initially as shorthand descriptor for the public institution of the discotheque, disco began to be used to refer to the music played in these settings, and when the Hues Corporation and George McCrae scored successive number one hits with the similar sounding "Rock the Boat" and "Rock Your Baby" in July 1974, it became clear that a new genre had come into existence.

Led by Paul Casella, Steve D'Acquisto and David Mancuso, DJs established the New York Record Pool, the first record pool in the United States, in June 1975, and soon after they persuaded a large gathering of major and independent record company representatives to start supplying them with free promotional copies in return for the de facto marketing they received every time a DJ played one of their records. DJs didn't only operate as tastemakers and marketers, however, and many of them became notable for the way in which they strung together their selections. David Mancuso (who considered himself to be a "musical host" rather than a DJ) pioneered the craft of piecing together records so they told a story that unfolded across an entire night. Francis Grasso used headphones and a mixer to blend records into a beat-matched flow. Nicky Siano asserted the creative power of the DJ when he began to interrupt records in mid-flow if the mix sounded right, and he also popularised the practice of working with three turntables simultaneously. Walter Gibbons became the first spinner to make his own homemade edits, and he also developed the art of mixing between the breaks of two records in order to create a "tribal aesthetic". Combining the distinctive styles of Mancuso and Siano, Larry Levan took the art of DJing to unmatched levels of artistry and drama. And although only a few spinners could play a conventional musical instrument ¾ Jim Burgess was a notable exception ¾ they demonstrated that the much-maligned practice of DJing was in fact a skilled art form.

Loleatta Holloway. Photograph by Waring Abbott.

Capitalising on the rising prominence of New York's DJs and the associated dance network, independent record companies such as Roulette, Scepter and 20th Century started to produce and mix records for the dance market, and when Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff of the renowned soul label Philadelphia International released "Love Is the Message" and "TSOP" by MFSB towards the end of 1973 it became clear that the music market was beginning to shift, with feel-good disco displacing message-oriented soul. The development was decried several years later by the critic Nelson George, who identified Philadelphia International's conversion to disco as a key moment in the decline of R&B. In reply it could be argued that disco was simply assuming an alternative form of engagement in its development of a politics of the body that deployed black aesthetics within a gay and feminist framework. Records such as "That's Where the Happy People Go" by the Trammps referenced disco's prominent gay male constituency, while the emotionally articulate Carl Bean, First Choice, Loleatta Holloway, Thelma Houston, Grace Jones, Chaka Khan, Evelyn "Champagne" King, LaBelle, D.C. LaRue, Cheryl Lynn, Sylvester and Karen Young joined Gloria Gaynor in forging disco as a terrain where masculinity could assume no easy dominance. Far from abandoning black aesthetic priorities, New York labels such as Prelude, Salsoul and West End recorded dance music that combined rhythmic drive with instrumental sophistication, while Florida's TK Records developed an eclectic, funk-tinged roster of artists that included Peter Brown, KC and the Sunshine Band, and T-Connection.

Development of the disco sound

In a parallel development, European producers started to release disco recordings in 1975, and their collective efforts soon acquired the label of Eurodisco. Silver Convention demonstrated the shift was aesthetic as well as geographical when "Fly, Robin, Fly" featured a strikingly heavy four-on-the-floor bass beat along with a clipped female chorus, and Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte entrenched Eurodisco's thudding four-on-the-floor bass drum motif when they recorded "Love to Love You Baby" with Donna Summer. These and other instances of early Eurodisco retained a connection with the soul orientation of US disco, but during the second half of the 1970s Eurodisco acquired a more obviously mechanical aesthetic. Although the self-consciously technological Kraftwerk are not normally associated with disco, recordings such as "Trans-Europe Express" were popular with many DJs, and Moroder produced an equally innovative and influential futuristic anthem when he teamed up with Summer to release the Moog-driven "I Feel Love". Gesturing towards the western classical tradition, Moroder and other prominent Eurodisco producers such as Cerrone, Alec Costandinos, Jacques Morali and Henri Belolo introduced elaborate orchestral instrumentation and grandiose conceptual themes in many of their recordings.

Eurodisco's rising share of the disco market was bolstered when the Los Angeles-based disco label Casablanca Records signed up a significant number of its most prominent producers and artists. Propelled by its hyperactive and uncontained owner Neil Bogart, Casablanca became the most commercially successful disco label of the second half of the 1970s, and counted Cher, Love and Kisses, and the Village People, along with the ubiquitous Donna Summer, among its most prominent artists. Disco acts on other labels also scaled the Hot 100, including the Bee Gees, Chic, Tavares, the Ritchie Family, Diana Ross, the Trammps, and Barry White, yet one-hit wonders such as Van McCoy ("The Hustle") and Carl Douglas ("Kung Fu Fighting") were also salient presence as well as an indicator of the ephemeral nature of many disco acts. Indeed that status even loomed over Gloria Gaynor until, who endured four years of failure until she scored her second hit, "I Will Survive", which was originally released as a B-side until DJs revealed it to be more effective than the A-side. The startling transience of these and many other disco artists can be partly explained by the fact that the rock-leaning record executives of the majors were notably reluctant to set up disco departments to help provide the genre's artists with a more consistent national profile. Yet as Will Straw has argued (1990), disco's relative fragility can also be traced to its consumers, whose primary concern tended to be the effectiveness of a particular recording in relationship to other contemporaneous recordings. In this disco differed from the rock market, where consumers were more likely to be committed to following the career of an artist or artists.

Instrumentalists and vocalists remained integral to the disco sound, yet as the 1970s unfolded a group of engineers, producers and remixers began to play a dominant role. Among this group, Giorgio Moroder and Alec Costandinos went on to enjoy reasonably successful artist careers, but the influential engineer Bob Blank and groundbreaking remixers such as Walter Gibbons, François Kevorkian, Tom Moulton and Larry Levan remained notably anonymous. Having reconstructed and extended records by artists such as BT Express, Don Downing, Gloria Gaynor, Patti Jo and South Shore Commission in order to make them more dance-floor friendly (often to the consternation of the recording artist), Moulton spearheaded the art of remixing. He also inadvertently recorded the first twelve-inch single when he placed a mix of an Al Downing song on a twelve-inch blank and was struck by the resulting increase in volume and sound quality. Designed to facilitate the circulation of extended records that could satisfy the needs of DJs and dancers, the twelve-inch single became one of the key innovations of disco, and the iconic format was commodified for the first time when Salsoul released a commercially available twelve-inch remix of "Ten Percent" by Double Exposure. The label also took the bold move of hiring Walter Gibbons to carry out the remix on the basis that a working DJ was more likely to understand how to reshape a record in the interest of the dance dynamic than a studio-bound engineer or producer. In this manner the twelve-inch single came to embody a dance floor sensibility, and Gibbons, who also completed groundbreaking remixes for Loleatta Holloway, Love Committee, Bettye LaVette and the Salsoul Orchestra, took the art of remixing into an experimental, leftfield direction. His far-reaching reconfiguration of Holloway's "Hit and Run", on which he was provided with access to the multitrack tapes of a recording for the first time, revealed the creative potential of remix culture.

From local scenes to mainstream saturation

While New York City remained the most important centre for private parties and discotheques throughout the 1970s, important scenes also developed in Boston, Los Angeles, Miami, San Francisco and Toronto, as well as cities in Europe and Asia. When the network of dance venues continued to expand during the economic slowdown that followed the oil crisis of 1973, commentators noted the way in which the entertainment institution of the discotheque provided good value for money in comparison to the cost of going to see live music, and during 1977 and 1978 three major discotheques ¾ Studio 54, New York, New York, and Xenon ¾ opened in midtown Manhattan. Competing over set designs, lighting systems, door queues and, most notably, the number of celebrities they could count as their clients, these venues began to appear regularly in New York's tabloid newspapers, as did more general interest features about disco culture. Some of the more thoughtful pieces discussed the way in which disco foregrounded novel ways of producing music and experiencing the body.

Far from being confined to urban centres, disco culture also expanded rapidly in suburban areas, where a markedly compromised version of the Loft/Sanctuary format took hold thanks to the fact that venues were often situated in ex-restaurants, DJs were given less autonomy, and couples dancing was re-popularised in the form of the Hustle. Nevertheless Suburban disco culture acquired an unexpectedly high profile when RSO released the film Saturday Night Fever, which was based on Nik Cohn's partly fictional account of Brooklyn discotheque culture for New York magazine. Released at the end of 1977, the film went on to generate the second highest box office takings of all time (behind the Godfather) and recording-breaking album sales (of thirty million copies). Starring John Travolta as the working-class Italian American shop-worker/dancer Tony Manero and a sound track dominated by the Bee Gees, the film portrayed disco as being both white and heterosexual, and this contributed to the rapid popularisation of the culture during 1978. Although it was less commercially successful, the Casablanca film Thank God It's Friday helped disco consolidate its growth, as did the annual Disco Forum, which was organised by Billboard magazine.

Previously sceptical about disco's aesthetic and commercial potential, major music companies including Warner Bros. and CBS responded to the post-Saturday Night Fever boom by establishing dedicated disco departments, and artists such as Alfredo De La Fe, Herbie Hancock, Johnny Mathis, Dolly Parton and the Rolling Stones started to record disco, albeit with mixed results. Around the same time WKTU, an anonymous soft rock station based in New York, switched to an all-disco format and increased its ratings from a one-point-three share to an eleven-point-three share overnight. Along with the sweeping success of Saturday Night Fever, the rise of disco radio encouraged the majors to switch their promotional focus from discotheque DJs to radio DJs, and they also took the decision to expand their disco output exponentially in the belief that anything that contained disco's recognisable four-on-the-floor bass beat would climb the charts. As a result, DJs and dancers alike were faced with a rush of disco releases that were deemed to be substandard, yet the shift towards a more profit-driven release strategy was not absolute, and 1978 saw the release of records such as Instant Funk's "I Got My Mind Made Up", which brought together many of the aesthetic borrowings and innovations of disco, as well as Sylvester's "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)", which included Patrick Cowley's synthesiser and served as an early imprint of the "San Francisco Sound". Released the following year and combining hard-edged drums, a prominent bass riff and shimmering vocals, Chic's seminal "Good Times" aligned the feel-good quality of the discotheque experience with black upward mobility.

Backlash

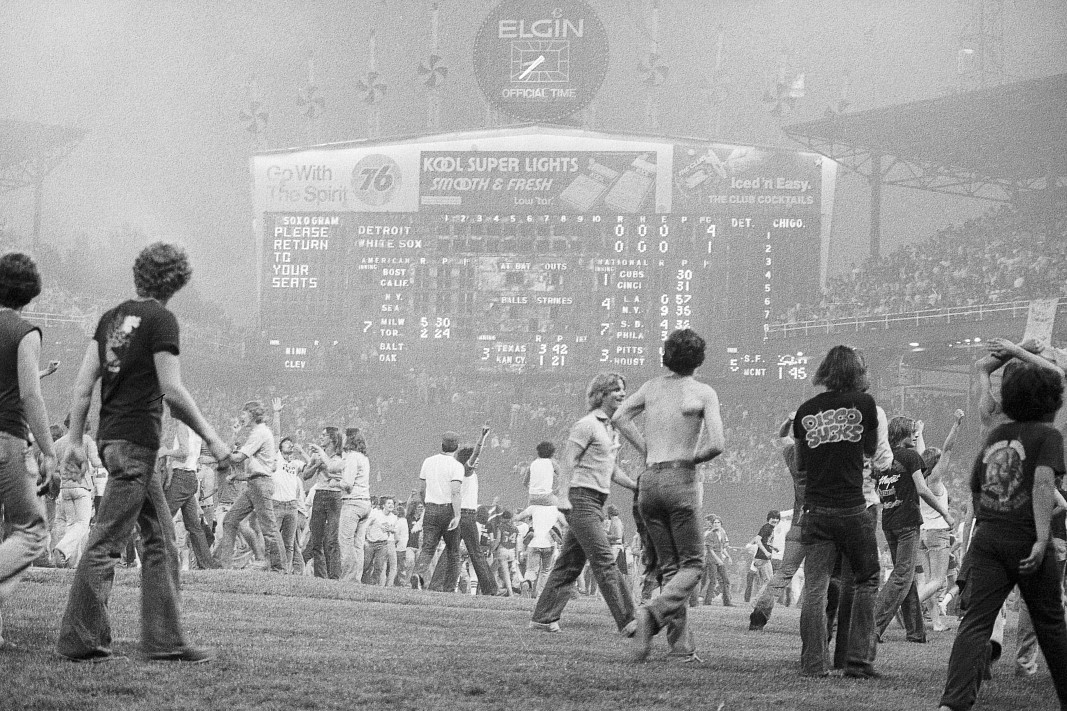

Disco reached a formal end-point during the second half of 1979 when the hostile "disco sucks" movement helped persuade record companies to abandon the generic label. Originating with John Holmstrom's "Death to disco shit!" editorial in Punk magazine, which was published in January 1976, the anti-disco movement acquired momentum gradually during 1976 and 1977, in part because disco's primary constituency was black, female and gay (in contrast to rock's white, straight and male demographic base), and in part because disco emphasised the female vocalist, the aesthetic of the collective groove, and the near-anonymous work of the producer and the remixer (whereas rock revolved around male musicianship, the primacy of the vocalist and the lead guitarist, and an ethos of authentic performative musicianship). The post-Saturday Night Fever proliferation of substandard disco records made disco increasingly vulnerable to attack, while the onset of a deep recession in the first quarter of 1979 contributed to the creation of a constituency of alienated young men who were searching for a scapegoat to blame for their lack of security. It was within this context that the backlash against disco peaked in the summer of 1979, and when the talk host DJ Steve Dahl staged an explosion of approximately forty thousand disco records in the middle of a baseball double-header at Comiskey Park in Chicago the movement reached its symbolic peak. During the next six months US record companies reduced their disco output radically, closed down disco departments, and started to use "dance" in place of "disco".

Disco Sucks riot at Comiskey Park, Chicago, 1979.

As consumers grew tired of the overkill of Saturday Night Fever, the limitations of suburban discotheque culture, and the unabashed elitism of Studio 54 and its imitators, thousands of discotheques closed during the second half of 1979, and disco soon ceased to be a media story. Yet in New York private parties such as the Loft and the Paradise Garage continued to flourish, while influential new dance venues such as Bond's, Danceteria and the Saint opened for business in 1980, just months after disco's reputed death. No finite distinction can be made between the disco records released during 1979 and the newly-coined dance output of 1980, and a record like Dinosaur L's "Go Bang!" contained enough links to disco for it to be hailed as one of the founding tracks of so-called "mutant disco". Yet the increasing prominence of synthesisers and drum machines during the first half of the 1980s signalled a shift in dance aesthetics, and the move towards a more technological sound was consolidated when the first tranche of Chicago house tracks were released during 1984. The rise of house in the middle of the 1980s marked a shift away from the skilled musicianship and often costly production processes of disco towards a culture in which music was made on cheap electronic equipment by untrained musicians, yet many of these younger producers attempted to ape the aesthetic priorities of disco, and house recordings have repeatedly featured samples from disco recordings. Early hip hop artists and producers also drew heavily on disco aesthetics, as did pop figures such as Michael Jackson and Madonna.

The failure of house to match the commercial impact of disco confined dance and its various offshoots to the margins of mainstream US pop culture during the 1980s, even if the genre achieved a more pronounced impact in Europe. Meanwhile the general shift in pop music culture towards the deployment of electronic and sequencing technologies resulted in disco acquiring a new significance. Often judged to have been slick and mechanical during the 1970s, by the early twenty-first century disco was notable for just how "live" it sounded in contrast to electronic dance genres such as house, techno, and drum and bass, as well as hip hop. The 1970s remains the last period in western popular music culture when trained musicians from a wide range of generic backgrounds (including funk, soul, rock, jazz and orchestral music) were employed on a regular basis to record music that would be played in dance venues, and this is one of the principle reasons the period has continued to be such a productive terrain for sampling. At the same time the 1970s practice of a DJ selecting records in relationship to a dancing crowd across the course of an entire night has remained the central dynamic of contemporary club culture, while the ethos of remix culture has stayed grounded in the principles forged by the likes of Tom Moulton and Walter Gibbons.

To sum up, the sound of disco emerged out of a wide range of danceable genres that were being played by DJs in the setting of the public discotheque and, less prolifically but perhaps more influentially, the private party. The sound came began to coalesce when a small number independent labels began to record music that was specifically designed for the nascent dance market and, around the same time, the music industry began to recognise that club play could boost a record's commercial performance. Consolidated during 1974 and 1975, the genre of disco featured a wide range of instrumental and vocal techniques that revolved around an uptempo four-on-the-floor bass beat (which ran at approximately one hundred and twenty beats-per-minute). Initially disco's open-ended structure enabled it to develop in eclectic and unpredictable ways, but during 1977 and 1978 a deluge of gimmicky releases drew on the genre's simple, easily identifiable rhythmic foundation, and in so doing undermined the credibility of the sound and contributed to its market collapse. The rise of disco-related genres such as house has led to a revival of interest in disco, especially in Europe, where house has enjoyed its most sustained level of success. Yet within the broader popular imagination, disco is regularly associated with "bad taste", and hip hop and rock commentators are often openly disdainful of the culture.

The literature on disco has been shaped by its shifting historical status. A flurry of books, many of them glorified dance manuals, came out in the US in late 1970s, when disco was enjoying its commercial peak; of these, Albert Goldman's Disco, which was published in 1978, is easily the most broad-ranging, even its content and voice are somewhat erratic, while Night Dancin' by Vita Miezitis provides an important turn-of-the-decade guide to the New York club scene. Published in 1979 and 1994 respectively, Richard Dyer's "In Defence of Disco" and Walter Hughes' "In the Empire of the Beat" contributed to the intellectual framing of disco, yet no book-length study appeared until 1997, when the US writer Anthony Haden-Guest published The Last Party, which framed disco through the lens of celebrity culture and Studio 54. Around the same time an alternative attempt to historicise disco within the context of dance music began to unfold in Europe, and while books by Ulf Postchardt (1995), Matthew Collin (1997) and Sheryl Garratt (1998) were heavily dependent on Goldman, Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton conducted original research for the two disco chapters that appeared in their broad-ranging account of DJ culture (1999). Following the publication of Mel Cheren's engaging if sometimes unreliable disco memoir, Keep On Dancing', the author of this entry researched the first book-length study of disco, Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-79, which came out in 2003. Since then, the British authors Daryl Easlea (Everybody Dance: Chic and the Politics of Disco) and Peter Shapiro (Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco) have contributed to the growing bibliography on disco, the length of which makes Shapiro's subtitle somewhat anomalous.

Bibliography

Aletti, Vince. "Discotheque Rock '72 [sic]: Paaaaarty!" Rolling Stone, 13 September 1973.

Brewster, Bill and Frank Broughton. Last Night A DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey. London: Headline, 1999.

Cheren, Mel. Keep On Dancin': My Life and the Paradise Garage. New York: 24 Hours for Life, 2000.

Cohn, Nik. "The Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night". New York, 7 June 1976.

Collin, Matthew (with contributions from John Godfrey). Altered State: The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House. London and New York: Serpent's Tail, 1997.

Dyer, Richard. "In Defence of Disco", Gay Left, summer 1979. Reprinted in The Faber Book of Pop, ed. by Hanif Kureishi and Jon Savage. London, Boston: Faber and Faber, 1995, 518-527.

Easlea, Daryl. Everybody Dance: Chic and the Politics of Disco. London: Helter Skelter, 2004.

Garratt, Sheryl. Adventures In Wonderland: A Decade of Club Culture. London: Headline, 1998.

George, Nelson. The Death of Rhythm & Blues. New York: Plume, 1988.

Goldman, Albert. Disco. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1978.

Haden-Guest, Anthony. The Last Party. Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1997.

Holmstrom, John (ed.). Punk: The Original. New York: Trans-High Publishing Corp., 1996.

Hughes, Walter. "In the Empire of the Beat: Discipline and Disco". In Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose (eds.), Microphone Fiends: Youth Music & Youth Culture. New York and London: Routledge, 1994, 147-57.

Lawrence, Tim. "Beyond the Hustle: 1970s Social Dancing, Discotheque Culture, and the Emergence of the Contemporary Club Dancer". In Julie Malnig (ed.), Social and Popular Dance Reader. Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2008, 199-214.

Lawrence, Tim. Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture (1970-79). Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004.

Miezitis, Vita. Night Dancin'. New York: Ballantine Books, 1980.

Postchardt, Ulf. DJ-Culture. Translated by Shaun Whiteside. London: Quartet Books, 1998 (1995).

Shapiro, Peter. Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco. London: Faber and Faber, 2005.

Straw, Will. "Popular Music As Cultural Commodity: The American Recorded Music Industries, 1976-1985". Ph.D. diss., McGill University, 1990.

Tolin, Steve (ed.). Disco: The Book. New York: Talent & Booking Publishing, 1979.

Filmography

Can't Stop the Music. Anchor Bay, 1980, directed by Nancy Walker, screenplay by Bronte Wood and Allan Carr.

Saturday Night Fever. Paramount Pictures, 1977, directed by John Badham, screenplay by Norman Wexler.

Discographical references

Brown, James. Give It Up or Turnit A Loose.' Sex Machine. King. 1115. 1970: US.

Chakachas. 'Jungle Fever.' Jungle Fever. Polydor. PD-5504. 1972: US.

Chic. "Good Times". Twelve-inch single. Atlantic. 37158. 1979: US.

Chicago Transit Authority. 'I'm A Man.' Chicago Transit Authority. Columbia. GP 8. 1969: US.

Dibango, Manu. 'Soul Makossa.' Fiesta Records. 51-199. 1972: France.

Dinosaur L. "Go Bang! #5" Remixed by François K. Twelve-inch single. Sleeping Bag Records. SLX-0. 1982: US.

Double Exposure. 'Ten Percent.' Remixed by Walter Gibbons. Twelve-inch single. Salsoul Records. 12D-2008. 1976: US.

Douglas, Carl. 'Kung Fu Fighting.' 20th Century Records. TC-2140. 1974: US.

Equals, The. 'Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys.' President PT-325. 1969: UK.

Gaynor, Gloria. 'I Will Survive.' Twelve-inch single. Polydor. 887 036-1.1978: US.

Gaynor, Gloria. 'Never Can Say Goodbye.' Never Can Say Goodbye. MGM Records. M3G 4982. 1975: US.

Hayes, Isaac. 'Theme from Shaft.' Stax. TAX 2002. 1971: US.

Hues Corporation. 'Rock the Boat.' RCA Victor. APBO-0232. 1974: US.

Intruders, The. 'I'll Always Love My Mama.' Philadelphia International Records. ZS8 3624. 1973: US.

Instant Funk. 'I Got My Mind Made Up.' Salsoul. SG 207. 1978: US.

Jo, Patti. 'Make Me Believe in You.' Wand. WND 11255. 1973: US.

Kendricks, Eddie. 'Girl You Need A Change of Mind.' People… Hold On. Tamla. T 315L. 1972: US.

Kraftwerk. 'Trans-Europe Express.' Trans-Europe Express. Capitol Records. SW-11603. 1977: Germany.

Love Unlimited. 'Love's Theme.' Under the Influence of Love Unlimited. 20th Century Records. T-414. 1973: US.

McCoy, Van, and the Soul City Symphony. 'The Hustle.' Avco. AV 4601. 1975: US.

McCrae, George. 'Rock Your Baby.' TK Records. TK 1004. 1974: US.

Melvin, Harold, & the Blue Notes. 'The Love I Lost (Parts 1 & 2).' Philadelphia International Records. S PIR 1879. 1973: US.

MFSB. 'Love Is the Message.' Love Is the Message. Philadelphia International Records PIR 65864. 1973: US.

MFSB. 'TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia).' Love Is the Message. Philadelphia International Records. PIR 65864. 1973: US.

Morrison, Dorothy. 'Rain.' Elektra 45684. 1970: US.

Olatunji. 'Jin-Go-Lo-Ba (Drums of Passion).' Drums of Passion. Columbia CS 8210. 1959: US.

Silver Convention. 'Fly, Robin, Fly.' Silver Convention. Jupiter Records. 89 100 OT. 1975: Germany.

Summer, Donna. "Love to Love You Baby". Love to Love You Baby. Oasis. OCLP 5003. 1975: US.

Summer, Donna. 'I Feel Love.' Twelve-inch single. NBD 20104. Casablanca. 1977: US.

Sylvester. "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)". Twelve-inch single. X-13003. Fantasy: US.

Temptations. 'Law of the Land'. Masterpiece. Tamla. STML 11229. 1973: US.

Trammps, The. 'That's Where the Happy People Go.' Twelve-inch single. Atlantic. DSKO 63. 1975: US.

WAR. 'City, Country, City.' The World Is A Ghetto. United Artists. UAS 5652. 1972: US.